AIR and Me

Part 2: Sapporo as art studio—since “Ripple Across the Water ’95”

By Shibata Hisashi

(Continued from Part 1: Sapporo as art studio—since “Ripple Across the Water ’95.” *See related video links at end)

First artist residents

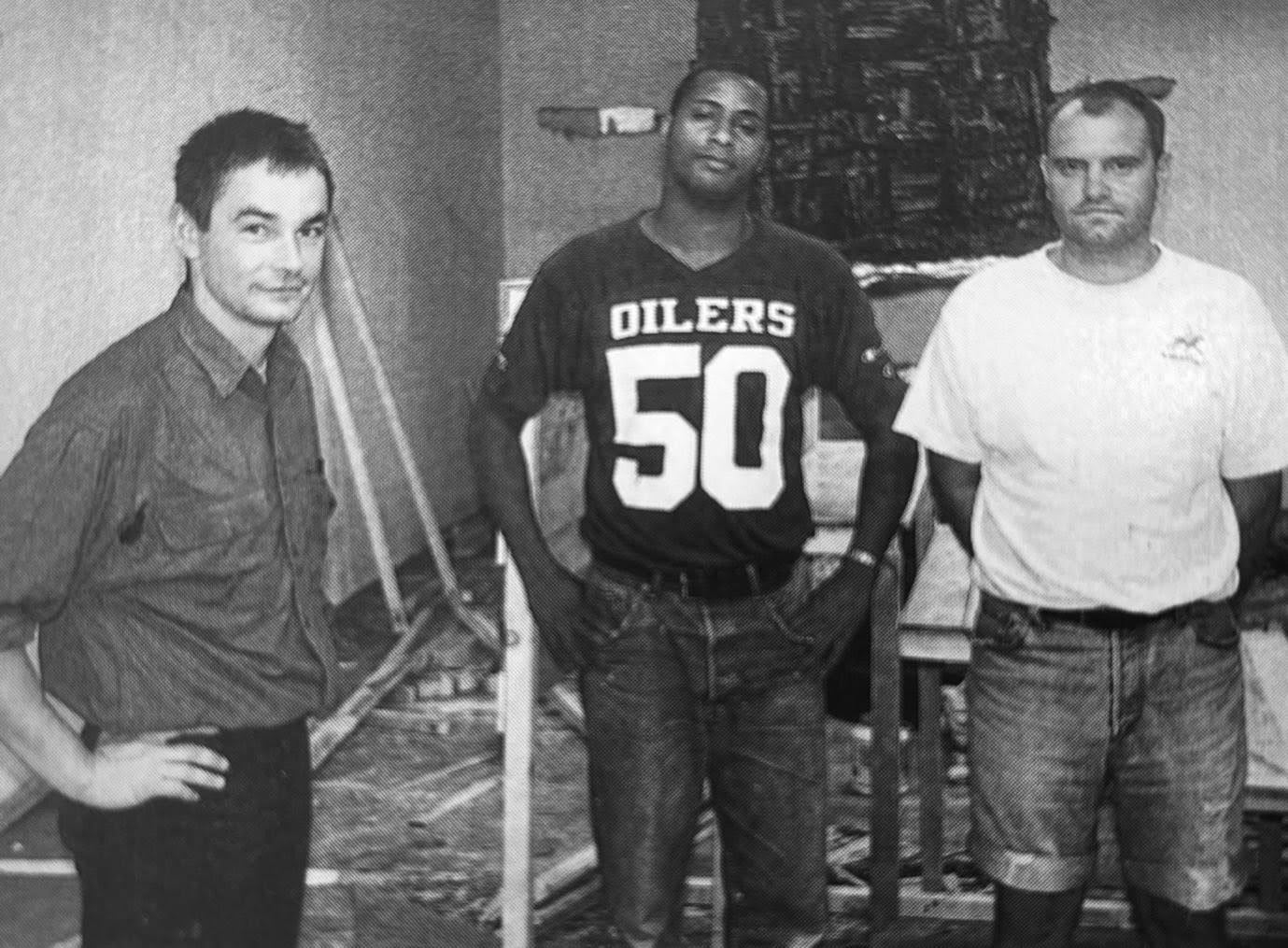

“Ripple Across the Water ’95” general director Jan Hoet invited three artists to Sapporo: Antoine Prum of Luxembourg, Avery Preesman from The Netherlands, and the American Jeffrey Wisniewski. (See Fig. 1)

They spent the height of summer in Sapporo making art for exhibition in autumn at “Ripple Across the Water ’95” in Tokyo (in Sapporo they staged a preview exhibition at the studio and ran workshops). At the risk of repetition, in the previous instalment I mentioned that the term artist-in-residence was not used at “Ripple Across the Water ’95,” plus, because the three artists were only in Sapporo for 2–3 weeks, they were not referred to as residents. On reflection, those weeks could probably be termed short-stay artist residencies, my overwhelming memory being of a brief but very intense time supporting creative production. Now I realize they were the first residents whose work I assisted with directly.

Search for studio space

The first challenge for those of us at Kita no Daichii 21 / Art Frontier, hosting our first fully-fledged residency for multiple overseas artists, was finding studio space.

Though I mentioned in the previous instalment that exhibition space was cheaper in the regions than the capital, the fact was that even in Sapporo, very few artists kept studios of their own.

As luck would have it however, we found the ideal space straight across from the Sapporo Factory complex housing our office. This was the Iwasa Building, a building of postwar construction on Kitasanjo-dori, once known as Kaitakushi-dori. The main attraction of this older building, which had been extended and altered over the years, was its high ceilings. On the ground floor there happened to be a 185-square meter space with a ceiling four meters high that had been a soft drink factory, then a photography studio. It was a stunning, loft-like location, and all anyone could ever want in a studio. (Later it was used for a year by the Recent Gallery contemporary art gallery where I was employed at the time, before becoming a theater, which it remains today. An attractive, high-vaulted old building, it later also came to house the Kaikai Kiki animation studio.)

Record of the residencies

The following are extracts from the “Poromenta Diaries” published in Bijutsu Pen, a free art criticism paper that circulated in Hokkaido in 1995, edited for reposting here. Though referring specifically to Sapporo, I think they give a fair idea of how people prepared for hosting early residencies, and how the hosting process played out.

July 11, 1995

Well the big day has finally come.

Nishimura Hideki (now editor-in-chief of Factory Magazine) and I were in my jeep heading for Shin-Chitose Airport to pick up artist Avery Preesman, arriving today from The Netherlands. All we knew was that he was a big, brown guy aged twenty-seven. We had his profile, but almost no information on his work. What was Jan Hoet trying to get out of Avery in Hokkaido? We were also nervous about trying to communicate with him, as neither of us had great English skills.

Turns out Avery is indeed a large fellow, about 190cm tall I suppose, son of a Dutch father and Caribbean mother. He came off the plane decked out casually in a dark red tracksuit top, jeans, and sandals, perfect for riding in my rundown jeep. Quick-witted and a music-lover, he has a delicacy one might not expect in someone his size. He said he had chosen for his Hokkaido material kombu seaweed, of all things. We immediately arranged to have 50kgs of (premium!) 2.5-meter-long Kayabe kombu supplied by an acquaintance of Nishimura-san’s. When asked for his thoughts on a studio and exhibition space, Avery said he would prefer somewhere with high ceilings. So we chose the former photography studio in the Iwasa Building on Sanjo-dori, one of the oldest office buildings in Sapporo. (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2. Avery Preesman’s work in the studio. The artist said he came up with the idea for using kombu as a material after hearing that natural kombu broth had been replaced by artificial flavoring. The work can be carried like a litter in an historical drama, and has Dutch flags for handles.

July 19, 1995

Eight days after Avery, the other two artists arrived. One was Antoine Prum. An affable chap from Luxembourg, he indicated he would use Japanese-made toys in his production. Apparently he works at a facility for the disabled, and loves children. His wife is actually due to give birth very soon, so he calls home daily, earning him the nickname of the “Telephone Checker.” To come to Japan to make art under these circumstances, showed how much the opportunity meant to him.

The other artist is the Polish-American Jeffrey Wisniewski, a sturdy fellow with an air of mischief. On arrival he immediately pulled a bottle of whiskey from his bag and started drinking straight from it. He says he wants to make his work using a Hokkaido boat that has been scrapped. Watch this space…

July 28, 1995

When it came to sourcing materials, of the three Jeffrey was the most challenging. He was excited and inspired by the boat scrapyard at Ishikari that he had visited first, and said he wanted to obtain a decommissioned vessel for his material. But the yard was on the riverbed and under rather complex mix of national and local administration, so it was unlikely we could negotiate anything in such a short time. A week or so passed, we still had not sourced a boat, and Jeffrey was still unable to start on his work.

On this day we were driving toward Hamamasu [*1] on the Japan Sea coast, on our third expedition to search for a boat. In saying that, we had nothing particular in mind; Jeffrey was starting to panic and growing rather irritable, so it was with his mental wellbeing in mind as much as anything that we had embarked on the journey.

The search for the elusive boat took us to the Hamamasu council offices, where we were directed further north to Ofuyu [*2], apparently full of the inshore boats known as isobune. This beach had the largest number of isobune we had seen so far. The problem was, all the working boats were fiberglass. Jeffery refused to countenance anything but a wooden vessel like those he had first seen. The choice of wood as a material, in the form of an old wooden type of transport, seemed to be significant because the Tokyo venue for his work was to be a BMW showroom.

Suddenly we noticed a boat abandoned in the long grass, and running over, stood around it. This was indeed a disused isobune, and most certainly of wood construction. Fortunately we were able to meet the owner, who intimated that the boat was a memento of his grandfather. When we explained our hopeful plans for it, he happily offered it to us for free.

Finally, we had found that elusive boat.

Thinking back 30 years, when we spotted that boat on the beach, it was smaller than the others, but it was actually a full seven meters long. When it came to transporting it from Ofuyu to Sapporo (about 100km), then to Tokyo for display, not to mention getting it to the studio, we would have no choice but to cut it into pieces.

With the owner’s permission we ended up chopping his ancestral keepsake in three to transport it and turn it into a work of art.

Fig. 3. Jeffrey Wisniewski’s work displayed at the BMW showroom in Aoyama was made from a disused wooden isobune boat from Hokkaido, PVC pipes, and sun umbrellas. The scattered golf balls may have been from the driving range in Sapporo, a revelation for the artist. Apparently he was startled to see people practicing a game like golf, usually played in wide open spaces, in an artificially partitioned place resembling a giant birdcage. (1995, writer’s photo)

Mingling of the ordinary and extraordinary

For those of us living in a provincial city somewhat starved of cutting-edge culture, living and engaging in creative practice with these foreigners from strange lands was an exhilarating mix of the ordinary and extraordinary.

During preparations for “Ripple Across the Water ’95,” following our initial meeting in Sapporo Jan Hoet returned to the city several times over the space of six months or so, occasionally in a private capacity. To take a break from his busy job no doubt, he would summon friends from at home in Belgium, hire a car and drive all over Hokkaido. [*3] I remember us having a great laugh on hearing that when someone had asked how one of these trips went, he had shouted, “When I tried to ask for directions, they all ran away! What’s going on?!” Foreigners were still an unusual sight in the Hokkaido countryside, and it was easy to imagine people fleeing when addressed in English. According to figures from 2022 for example, these days the number of foreign residents in Hokkaido is at an all-time high. Yet, even if not to the extent of 30 years ago, I suspect there are still those who are nervous of foreigners, and communities distrustful of cultural diversity. [*4]

Jan Hoet went out drinking a few times with the residents and those of us in the Sapporo office. The cheap izakaya we frequented had a karaoke machine, and the residents visiting Japan, and we their local support staff, became sole witnesses to the sight of the all-conquering documenta curator climbing on a table with the mike to hoarsely belt out an excruciatingly bad version of Love Me Tender… Encountering the extraordinary amid the ordinary: this scene, of the sort that is part of the appeal of the artist residency, in which living and creating are connected, is one I will certainly never forget as long as I live.

Fig. 4. From right, Kita no Daichii 21 / Art Frontier head Nishimura Hideki, Jan Hoet, local student volunteer Kasai Shie (courtesy Kasai Shie, photographer unknown).

(To be continued)

Part 1: Sapporo as art studio—since “Ripple Across the Water ’95”

[*1] The village of Hamamasu. Located on the Japan Sea coast in the far north of the Ishikari Subprefecture, approximately 80km from Sapporo.[*2] Fishing village on the Japan Sea side of Hokkaido approximately 100km from Sapporo, between Hamamasu and Mashike.

[*3] In Jan Hoet: on the way to documenta IX by Alexander Farenholtz and Markus Hartmann (Yobisha) Hoet is described during preparations for documenta IX as racing at high speed around Germany. For Hoet driving seems to have served as a valuable diversion.

[*4] From the Hokkaido prefectural website (viewed June 11, 2025).

The following are videos recorded in 2022, with behind-the-scenes information on the project, including the miraculous episode involving local university student Kasai Shie, the volunteer in Fig. 4 whose work caught the eye of Jan Hoet.

SHIBATAIWA#6 Jan Hoet “Ripple Across the Water ’95” Conversation Part 1 (viewed June 11, 2025)SHIBATAIWA#7 Jan Hoet “Ripple Across the Water ’95” Conversation Part 2 (viewed June 11, 2025)

Shibata Hisashi

Director, NPO S-AIR / Director, AIR network Japan

Professor, Art Project Lab, Hokkaido University of Education, Iwamizawa

Shibata established Sapporo Artist in Residence (S-AIR) in 1999, which was registered as a non-profit organization in 2005 and awarded the Japan Foundation Prize for Global Citizenship in 2008. To date, S-AIR has hosted 106 international artists from 37 countries and regions, and sent 24 groups of Japanese artists to 14 countries for art residencies. Became a professor in 2014 at Hokkaido University of Education, Iwamizawa, where he heads the Art Project Lab. Co-author of What will change with the designated manager system? (Suiyosha), Basic research into the promotion of regional culture through art and cultural facilities utilizing abandoned schools (Kyodo Bunkasha), and Artist in Residence – The potential to connect towns, people, and art (Bigaku Shuppan).