Out of Kyoto

001 Does Marcel Duchamp still matter?

By Ozaki Tetsuya

The results of a survey on “the father of contemporary art” were published in German online magazine Weltkunst1 and the English-language artnet.2 Conducted by Thomas Girst, co-curator of the exhibition “Marcel Duchamp in Munich 1912”3 staged at Munich’s Lenbachhaus in 2012, the survey was titled “Does Marcel Duchamp Still Matter?” The survey attracted 23 responses, including from artists Jeff Koons, Ai Weiwei, Subodh Gupta, Cao Fei, and Samson Young, and curators Chris Dercon, Klaus Biesenbach, the late Koyo Kouoh, Susanne Pfeffer, and Philip Tinari.

The choice of Fountain (1917) as the most influential artwork of the 20th century in a 2004 survey of 500 British art experts was also noted in my book Gendai āto to wa nani ka (What is contemporary art?).4 At the time, public understanding of Duchamp was largely confined to “Oh yes, the urinal guy,” but these days, even those who make their living in the art world are probably barely more informed. Duchamp’s name does not arise very often when talking to artists, curators and gallerists. The above survey was likely prompted by plans for a major Duchamp retrospective in 2026,5 but also seems to reflect the current dominance of socially engaged practice in contemporary art, and disregard for the “father.”

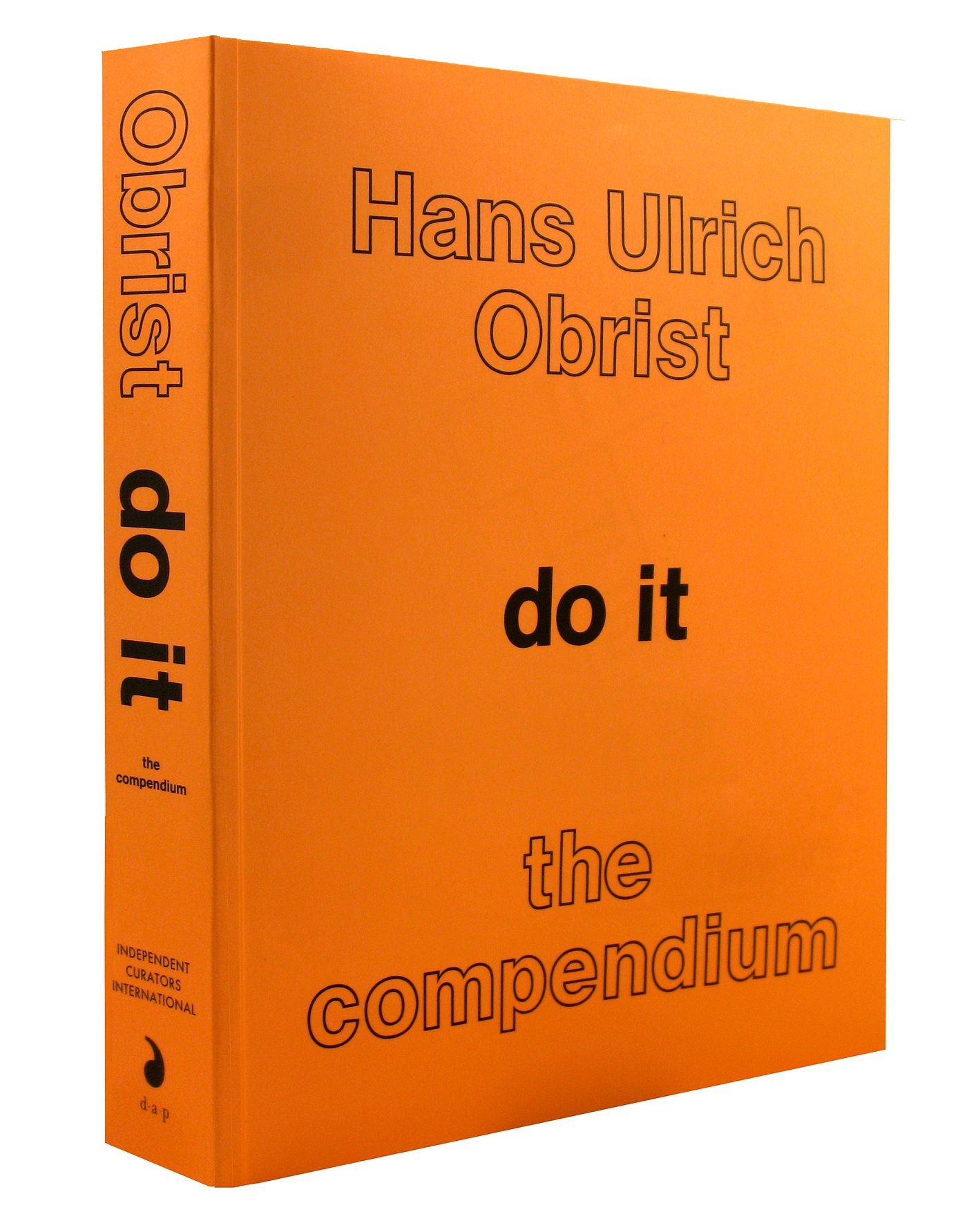

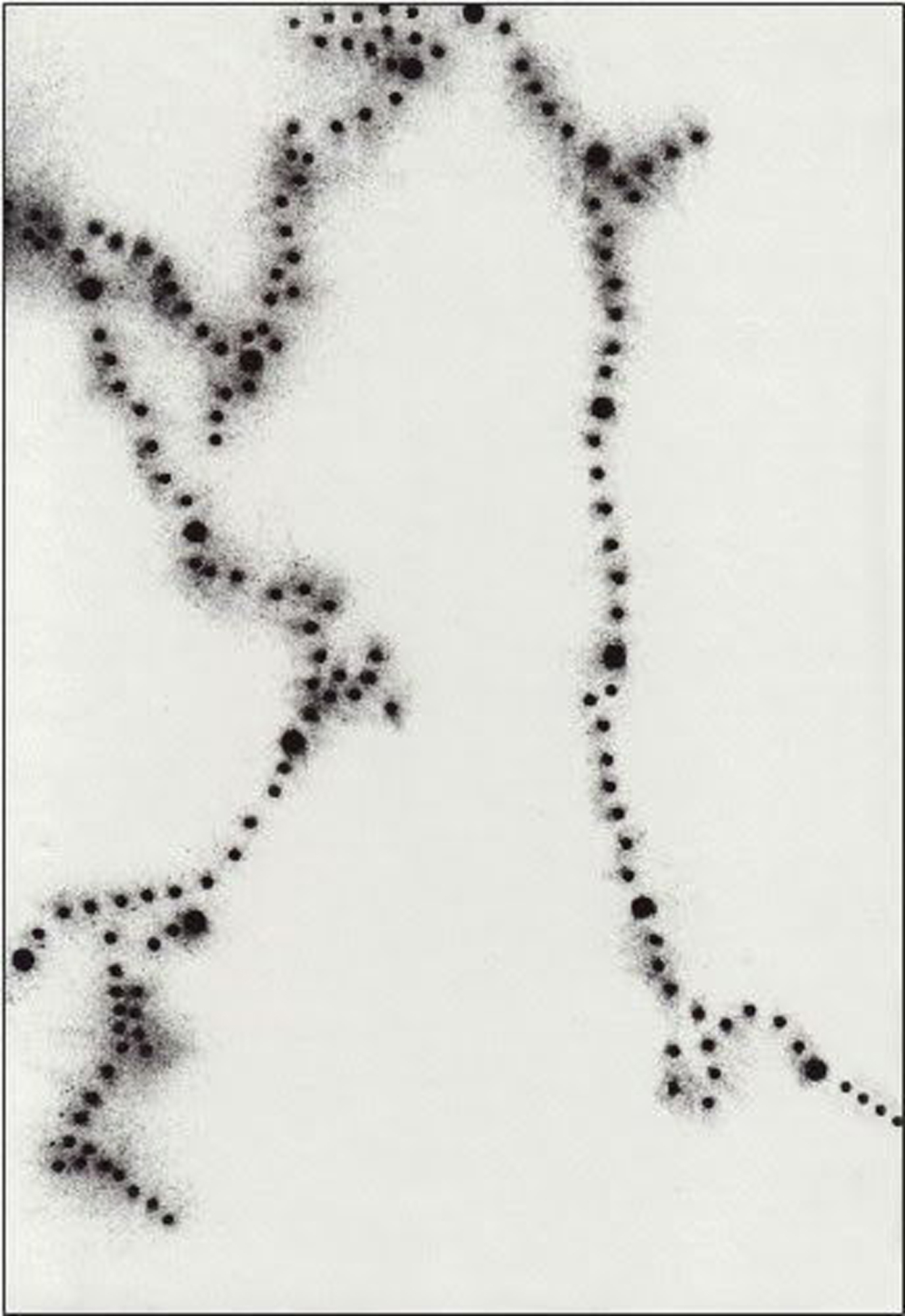

The longest of the 23 responses was 172 words. Though unsurprising considering their brevity, virtually none of the respondents’ views warrant special attention. Hans Ulrich Obrist does reveal (albeit not for the first time) that his project do it,6 running since 1993, is inspired by Duchamp’s Unhappy Readymade7 and In the Infinitive (À l’infinitif) (also known as The White Box).8 The former is a readymade that no longer exists, made by the artist’s sister in Paris using instructions supplied in a letter sent by Duchamp during a stay in Buenos Aires, and the latter a collection of notes written in the early 1910s when he was working on ideas for readymades and The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (more commonly called The Large Glass), and first published about half a century later in 1966.

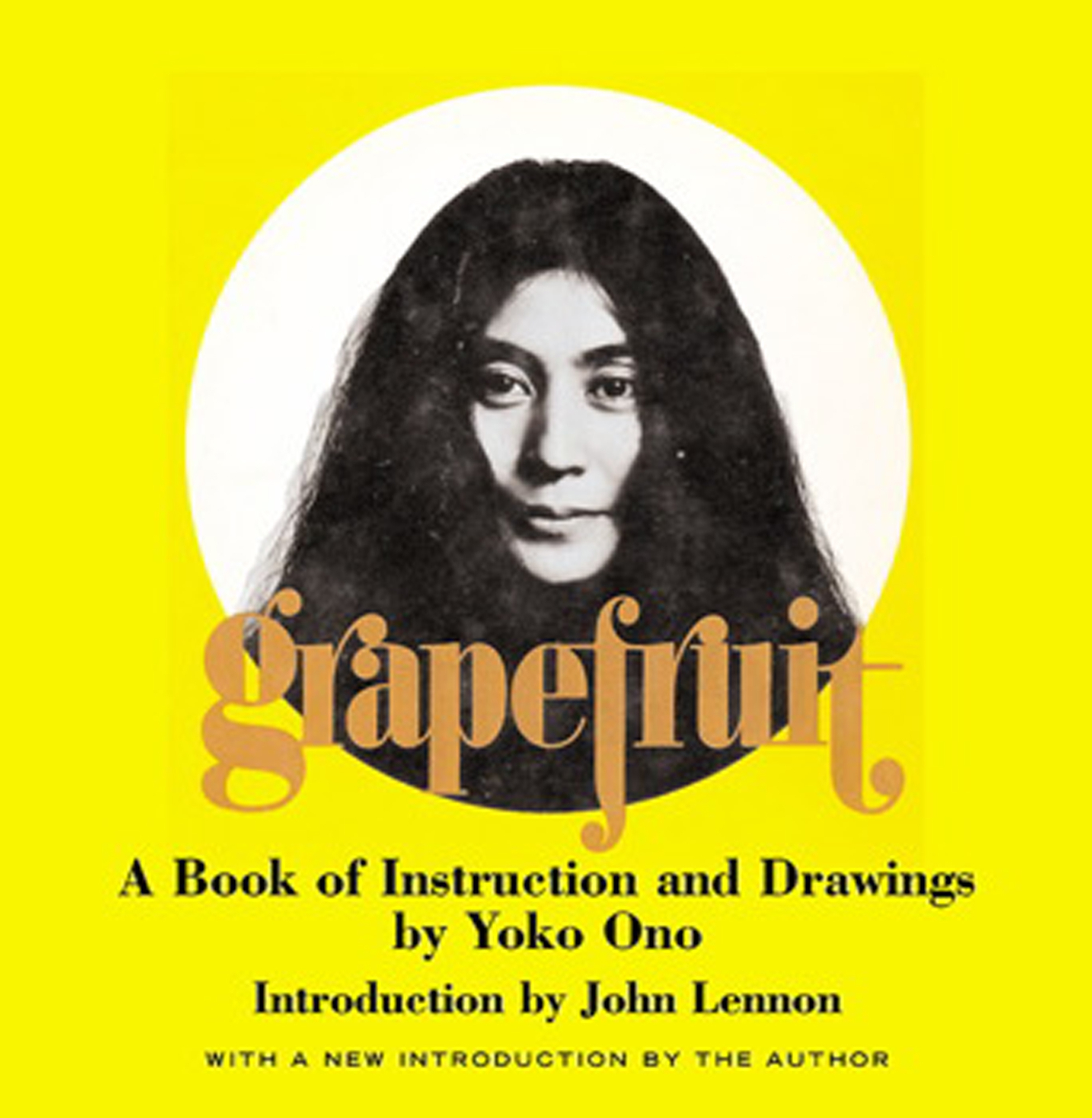

The project and book of the same name compiled by Obrist, do it (2004), contain works by over 160 artists. All are instruction art, with just a few “instructions” also contributed by musicians, poets, novelists, philosophers, architects and filmmakers. As well as Duchamp the foreword mentions the Surrealists, Situationists, and a handful of literary scholars, but the greatest honors appear to be reserved for the likes of George Brecht of Fluxus fame, and Yoko Ono with her book Grapefruit (1964).9 Ono’s contribution to do it, Wish Piece, needless to say was written for Wish Tree (1996–).10

Hans Ulrich Obrist (éd.), Do it: The Compendium, Independent Curators International & D.A.P., 2013.

Yoko Ono, Grapefruit: A Book of Instruction and Drawings, Simon & Schuster, 2000.

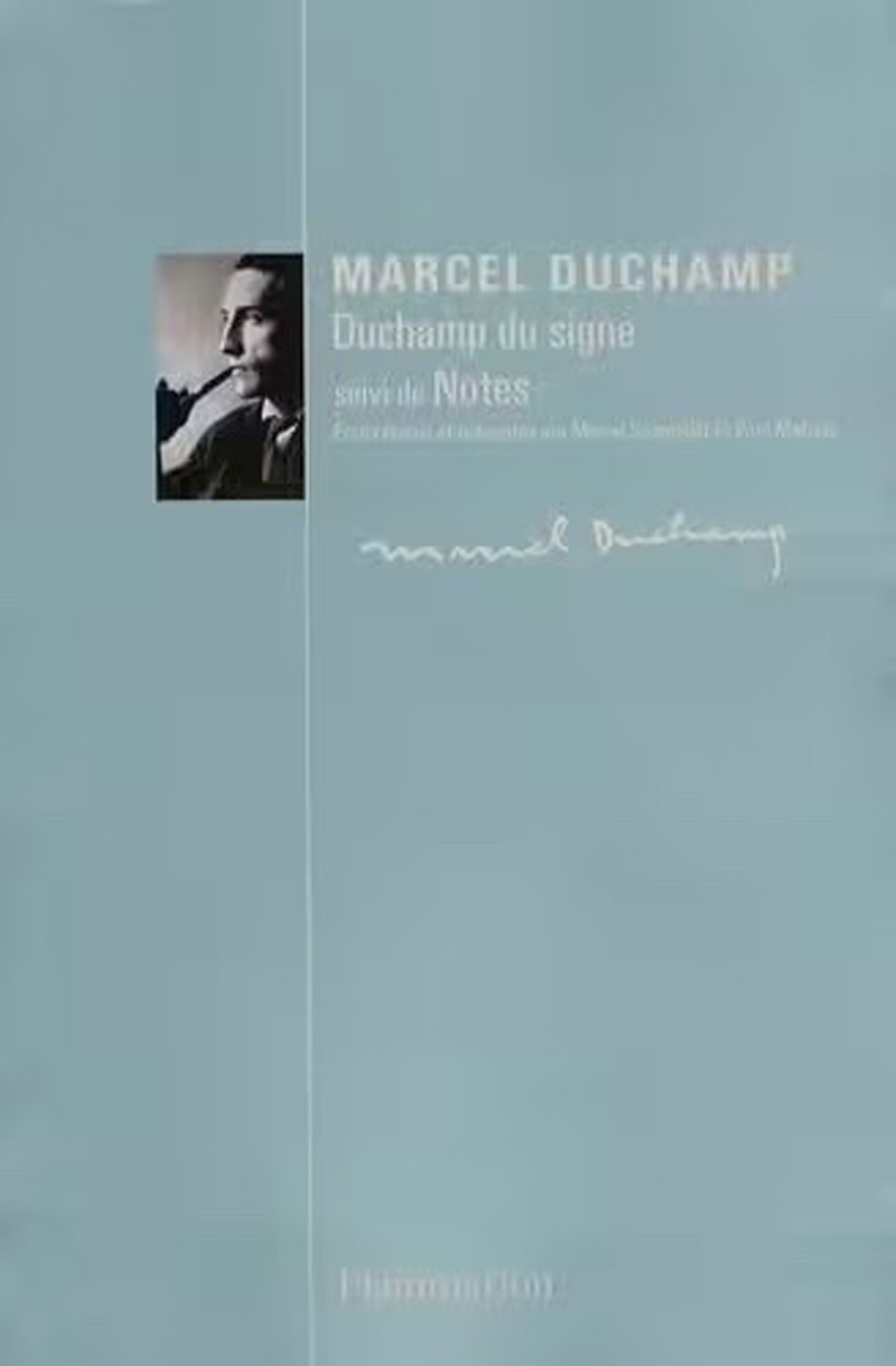

Though it was good to reaffirm the Duchamp–Brecht, and Ono–Obrist channels, suddenly I wondered whether Duchamp’s texts and main interviews were still being read. In the aforementioned survey, likewise, curator Shaleen Wadhwana worries that if art school curricula were to change, the next generation of students and art lovers might no longer learn the importance of Duchamp. The collected writings of Duchamp are still available for purchase in French,11 English12 and Japanese.13 So how many people working in art have read them?

*

The White Box includes numerous geometrical observations on the fourth dimension, and is deemed a foundational text for study of The Large Glass alongside The Green Box (1934) (both are included in Duchamp’s collected writings). More important to artists and art lovers however is the line “Can works be made which are not ‘of art’?” No other artist I know of has ever posited such a fundamental question. The readymade is what emerged from its deep contemplation, and it is here that the history of contemporary art began.

Since then, countless works have been offered up as readymades. And not only objets d’art or assemblage-type pieces. The works of leading practitioner of “relational art” Rirkrit Tiravanija,14 for example, can surely be termed “readymades of (intangible) things” because Tiravanija chooses, names and gives new meaning to intangible “things” like cooking, parties and live music gigs in the same manner as readymades of tangible things (ie objects). Or take the “tasks” popular in contemporary dance of the 1960s: these can be seen as “’movement’ readymades.”15

Yet at the point when Duchamp was conceiving of/assembling his readymades, these were works “not ‘of art’.” Note, as mentioned above, that The White Box was published in 1966. With Duchamp himself preferring to dodge the question, the definition of readymade proffered by Andre Breton in 1938 of “an ordinary object elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist”16 is still deemed to be correct. Many museums adopt or invoke Breton’s view, starting with the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which holds the main Duchamp works17 and including the Museum of Modern Art in New York,18 Pompidou Center,19 and Tate Modern.20 Much critical discourse on the subject is also based on the same understanding.

The technique of the readymade is now universally recognized, with some fine examples already occupying a place in art history. It would now be difficult, institutionally, to acknowledge these seminal works as “not ‘of art’.” The “definitions” on the websites of these museums remain unrevised, and a similar mentality probably lies behind the assumption by critics, when pursuing any discussion on Duchamp’s readymades, that they are art. Although this could simply be because these critics have not read The White Box.

Perhaps by now, it does not really matter. What does matter however, is that the question that Duchamp pondered is not one shared, so the number of artists and curators turning their thoughts to the fundamental, essential issue of what exactly constitutes contemporary art, seems to be in declining dramatically. Yes it is unlikely that anyone will be thinking an artwork “just has to be beautiful,” but there still seem to be a lot of practitioners and others in the art sector mistakenly thinking that “it just has to reference a previous work” or “just has to include a politically correct assertion” or “just has to use cutting-edge technology.”

I personally believe that works like The Large Glass and Given address monumental themes beyond the generally accepted one of eros. Both are based thoroughly in thinking of the most fundamental kind, and have been crafted as “works ‘of art’” and “works that can only be ‘of art’.” Artists ambitious enough to pursue such thinking, and tackle such huge themes, may be a vanishing breed, but they do exist (or so one would like to think). As long as artists aspire to surpass their “fathers,” Duchamp will always matter. Whether that aspiration is achievable, is of course another discussion entirely.

Marcel Duchamp, Duchamp du signe – Suivi de Notes, Flammarion, 2008.

Marcel Duchamp, The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, Da Capo Press, 1989.

Marcel Duchamp, Maruseru Dushan zen chosaku, [Marcel Duchamp, the complete writings], ed. Michel Sanouillet, trans. Kitayama Kenji, Michitani, 1995.

-

1. Thomas Girst, “Ist Marcel Duchamp noch wichtig?” Weltkunst, February 2025

2. “Does Marcel Duchamp Still Matter?”, Artnet News, February 2025.

3. “Marcel Duchamp in Munich 1912”, Lenbachhaus München.

4. Ozaki Tetsuya, Gendai āto to wa nani ka [What is contemporary art?] (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2018).

5. Starting at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, and touring to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which houses Duchamp’s major works, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. The Pompidou is currently undergoing renovations, so the venue will be the Grand Palais. Details of the MoMA show below.

“Marcel Duchamp: The Barbara and Aaron Levine Collection”, MoMA.

6. “do it (2013)”, Independent Curators International.

7. “Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912”, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

8. “À l’infinitif (The White Box), 1966”, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

9. Yoko Ono. Grapefruit. Simon & Schuster, 2000.

10. “Wish Tree (Yoko Ono art series)”, Wikipedia. , “Wish Tree for Yoko Ono”./

11. Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp du signe: Suivi de Notes. Paris: Flammarion, 2008.

12. Marcel Duchamp, The Writings of Marcel Duchamp, ed. Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson. Da Capo Press, 1989.

13. Marcel Duchamp, Maruseru Dushan zen chosaku [Marcel Duchamp, the complete writings], ed. Michel Sanouillet, trans. Kitayama Kenji (Michitani, 1995).

14. “Rirkrit Tiravanija”, David Zwirner.

15. Yvonne Rainer spoke of “tasks” being about “found object, found movement.” (Connie Butler, Yvonne Rainer, in The Museum of Modern Art Oral History Program, July 7, 2011, p.34)。However Duchamp stated that found objects were different to readymades because they are selected according to the artist’s personal taste (aesthetic sensibility). Most tasks are not especially aesthetic, and are based on quotidian actions, so may properly be referred to as readymade.

16. André Breton, Paul Éluard, Dictionnaire abrégé du surréalisme, 1938, p.23

17. “Duchamp’s Fountain and the Role of Information”, Philadelphia Museum of Art.

18. “Marcel Duchamp and the Readymade”, MoMA.

19. “Ready-made: Voulez-vous un dessin ?”, Centre Pompidou.

20. “Readymade”, Tate Art Terms.

(All accessed August 22, 2025).

About the series

In “Out of Kyoto” writer and art producer Ozaki Tetsuya covers topical issues in the arts and wider culture, exploring the state of artistic expression today, from an historically-informed perspective.

Ozaki Tetsuya

Writer/arts producer. Launched the online culture magazine REALTOKYO in 2000, and the contemporary art magazine ART iT in 2003. General producer of the performing arts program for Aichi Triennale 2013. Served from September 2012 through December 2020 as publisher and editor-in-chief of the online culture magazine REALKYOTO, and from February 2021 through March 2025 as editor-in-chief of REALKYOTO FORUM. Editor and author of the photo books One Hundred Years of Idiocy and its sequel One Hundred Years of Lunacy >911>311; author of Gendai āto to wa nani ka (What is contemporary art?) and Gendai āto o korosanai tame ni (So as to not kill contemporary art). Awarded the Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French Government in 2019.