AIR and Me

Part 3: The first map

By Shibata Hisashi

In search of the first AIR map

Previous instalments in this series discussed the “Ripple Across the Water ’95” project in my then home of Sapporo as an example of an artist residency from just prior to the term “artist-in-residence (AIR)” gaining currency in Japan.

That year, 1995, there was much talk around me, directly and indirectly, of AIRs, including of a local artist of my acquaintance being invited to the Worpswede artist colony1 in Germany, renowned in Europe for its grassroots role in AIR history. In the West the institution of the AIR in its modern form is deemed to have emerged in the 17th century, and speculating that Japanese artists too had long been using the AIR system to spend time in the West and elsewhere, people around me had begun to say that Japan needed something similar.

Then two years later, in 1997, Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs launched its Artist-in-Residence Program. This was the beginning of official efforts by the state to promote artist residencies across Japan, and it would be reasonable to say marked the start of AIRs as a nationwide phenomenon. Obviously there had been earlier AIR schemes, such as Villa Kujoyama,2 started by the French government in 1992 and more or less ongoing ever since; and local government initiatives like the Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park Artist in Residence3 also established in 1992, and ARCUS Project4 in Ibaraki, in 1994, plus a handful of arts and cultural villages in various locations, and AIR-style support by private individuals. I imagine there were also places around the country that experimented with the arts/culture village concept, however no national data seems to be available on this.

I first learned about the Agency for Cultural Affairs invitation to apply for AIR assistance in 1998, the second year of the program, and requested the relevant information and forms, including the conditions for application. These came with a map showing the locations of AIRs across the country (Fig. 1). Unfortunately, as I had the Agency fax the information, and did not make a copy, 27 years on, the map has faded and is no longer really legible. The map showed only those AIR programs selected for Agency support for this particular year, but as the first map of Japanese AIRs I had ever laid eyes on, it made quite an impression. A few years later I decided to try restoring it. My attempts included heating the map with a hair-dryer, cooling it in the fridge, and editing an image of it on my computer, but these efforts met with only limited success, and the smaller script remained impossible to read.

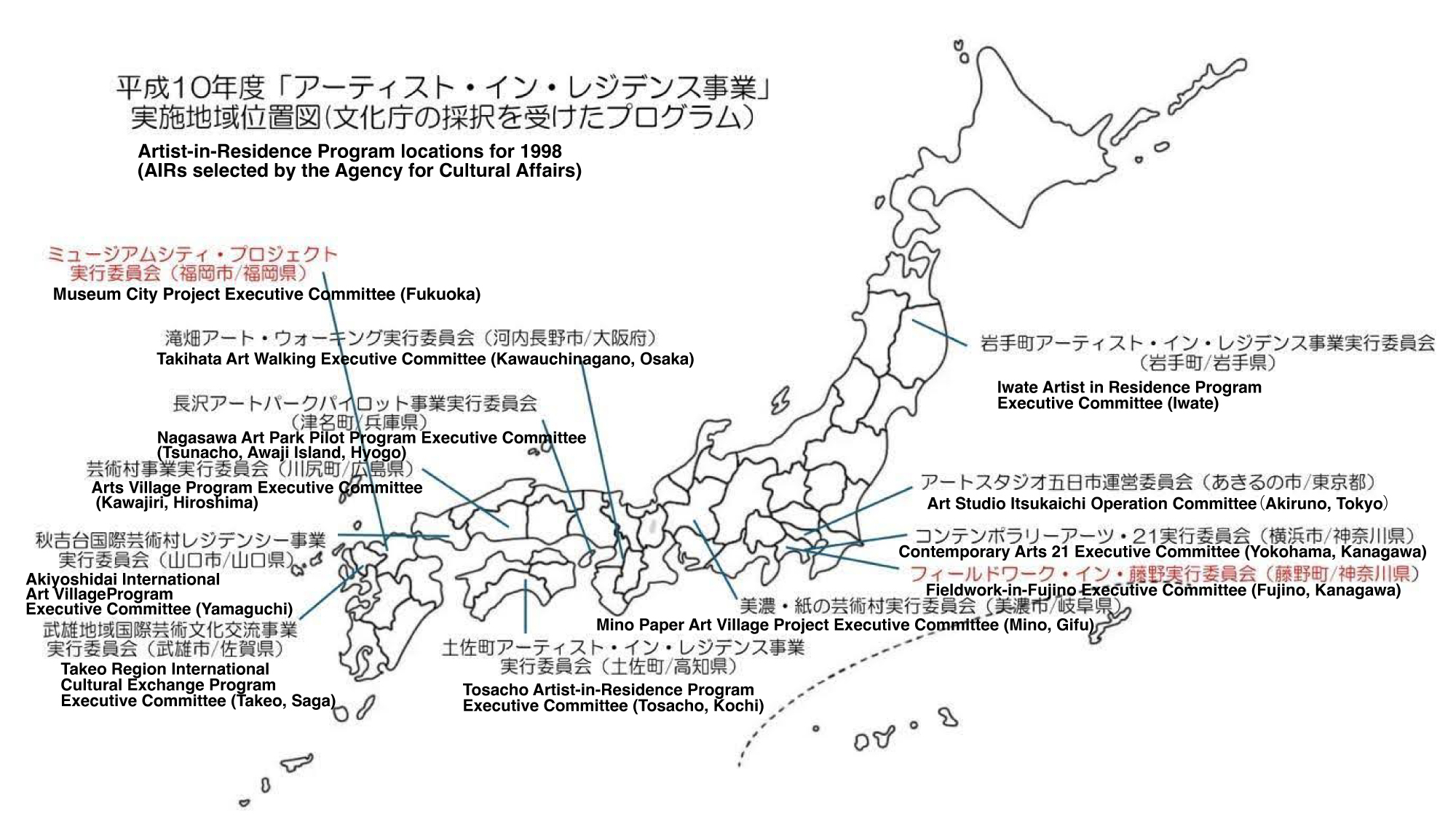

I inquired around for a copy of this first map of the AIR sector in Japan, but to no avail, so obtained a photocopy of the monthly bulletin of the Agency for Cultural Affairs from the National Diet Library, where I found a list. Using this data I drew up a restored version of the original I already had; the result was Fig. 2 (showing the 12 AIRs selected).

Fig. 2 Map showing 1998 Agency for Cultural Affairs Artist-in-Residence Program locations

Red text indicates a new addition (Map compiled by author from Agency sources)

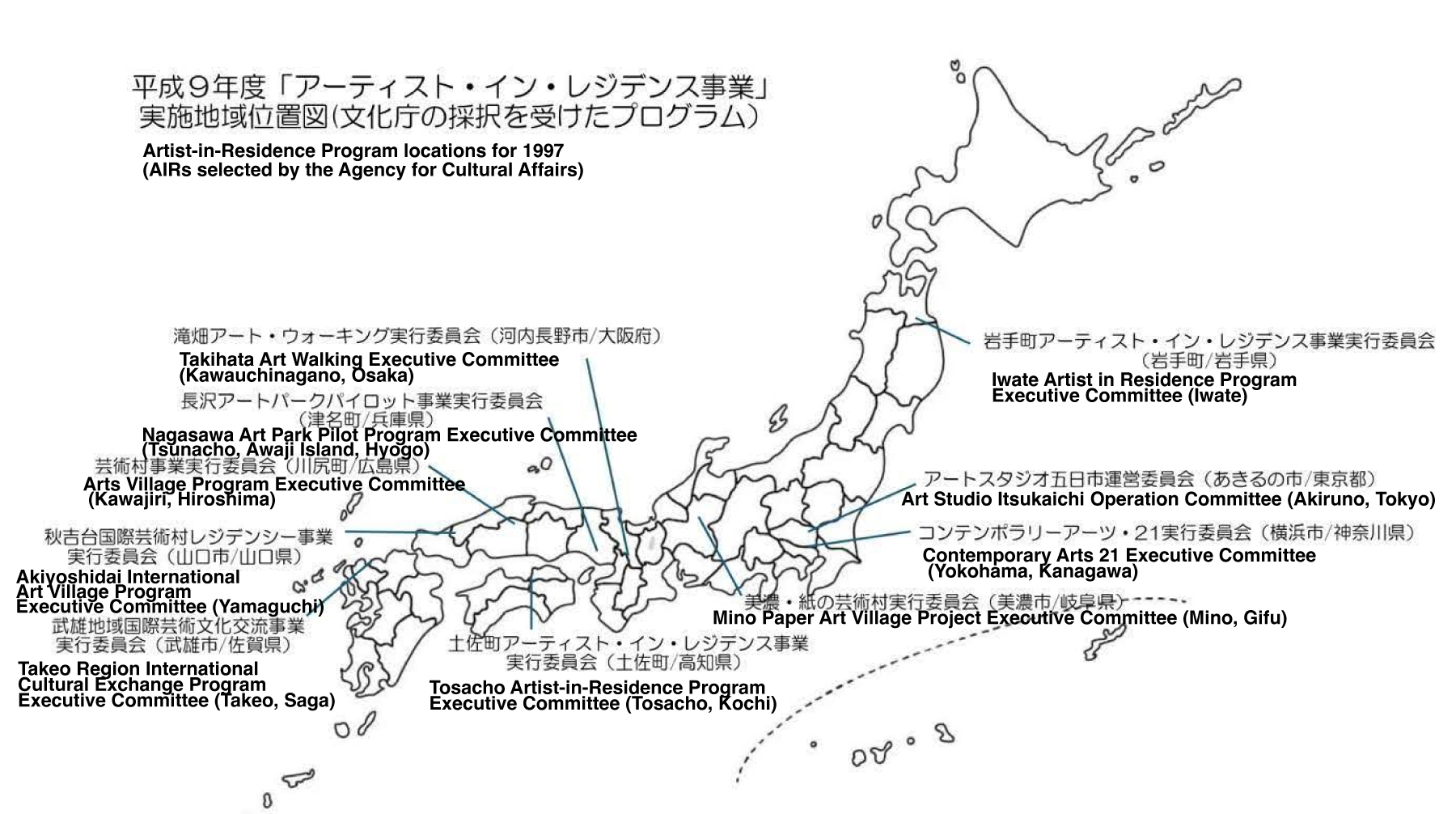

Fig. 3 in turn is a map I drew up, based on Fig. 2, showing the AIRs (10) chosen for the first year of the program. I have no idea if such a map actually existed, and it is limited to AIRs in the Agency for Cultural Affairs program, but may well be the first such map covering the whole of Japan.

Fig. 3 Map showing Agency for Cultural Affairs “Artist-in-Residence Program” locations in first year of program (1997)

Features of the early Agency for Cultural Affairs AIRs: The executive committee

An interesting feature of the early AIR maps is the almost invariable inclusion of “executive committee” in the titles of the AIRs. With the Art Studio Itsukaichi alone making reference to an operation committee, this means that all these programs operated with an executive committee format. The Sapporo non-profit S-AIR that I represent, incidentally, has been running since its selection in the third year of the Agency for Cultural Affairs program (1999), originally as the “Sapporo Artist in Residence Executive Committee” (Fig. 4). The name S-AIR was originally an abbreviation for Sapporo Artist in Residence, before its adoption as the official name on incorporation as a non-profit in 2005.

One can understand why there are no incorporated non-profit organizations or general incorporated organizations on the map, due to the lack of NPOs at the time (the NPO Law only coming into force in 1998), but it struck me that for so many of these listings to be identical, there must have been guidance of some sort from the Agency for Cultural Affairs when applying. So I took another look at documents from the time, and found the term “executive committee” in the example shown under the conditions for making an application. The section for budget documents was separated into Agency for Cultural Affairs, local authority, and other allocations, and applicants probably used the term executive committee here as well.

I seem to remember that when my own organization was first applying, it said private organizations could apply as well as local authorities, so in the first instance we copied the example and called ourselves an executive committee.

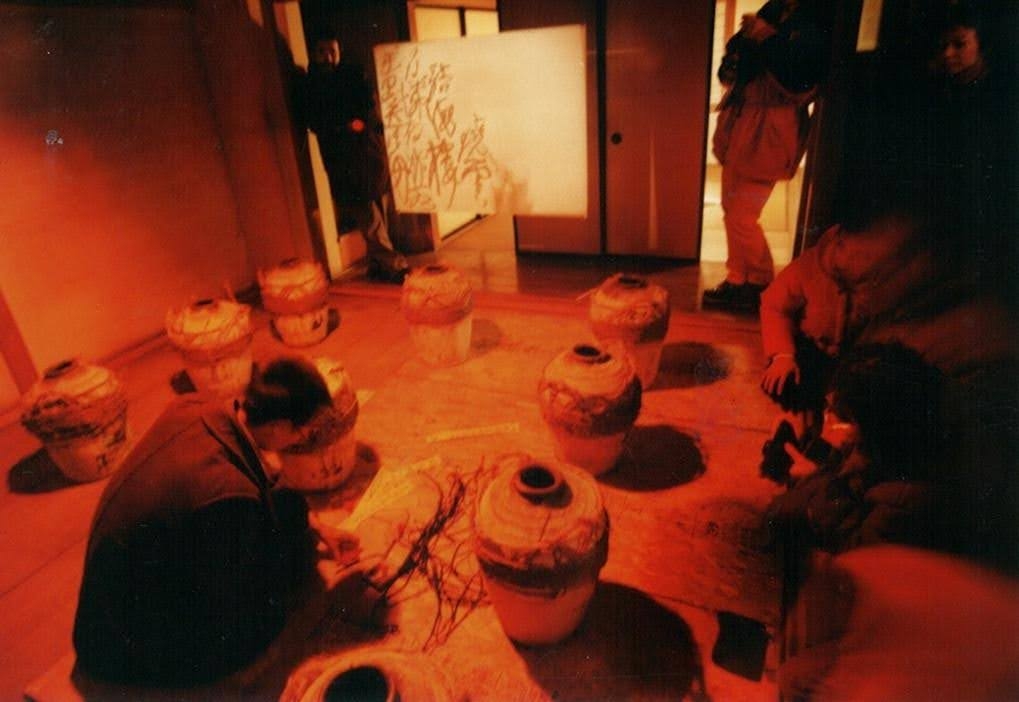

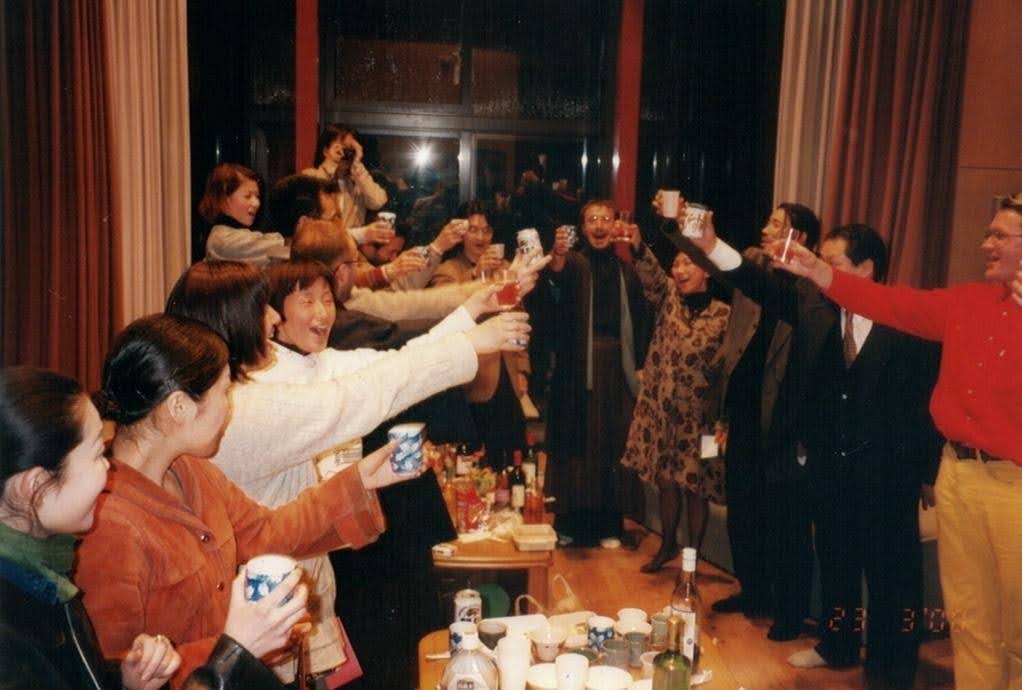

Below: Images from Sapporo Artist in Residence Executive Committee activities in the AIR’s first year, 1999. Seven artists were hosted for periods of one to six months.

Fig. 4-1 Isozaki Michiyoshi, Sora tobu biniiru daikyojin in Sapporo (Flying plastic giant in Sapporo), at Sapporo Chuo Elementary School.

As our application came under the jurisdiction of the Hokkaido education board, for a while afterward we ran a series of popular workshops for children. The elementary school serving as the venue here was in central Sapporo, but slated for closure.

Fig. 4-2 Solo exhibition by Qiu Zhijie, staged in a former bathhouse. The work Ten poems for Sapporo consisted of instructions to read verses from the Tang Dynasty, seal the mystical power of language into empty Shaoxing rice wine jars, and bury them in the ground within Sapporo city limits. There was also a video work in which text vanished as it was written, as if erasing history. (Qiu Zhijie went on to stage an exhibition at the 21s Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa in 2018, and mentions production during his Sapporo residency in an interview filmed at the venue.)

Fig. 4-3 Party at the AIR studio/accommodation at Sapporo Art Park. As a living space one could not wish for anything more, but the site’s distance from the city and lack of internet or fax communications led to a change of location from the following year.

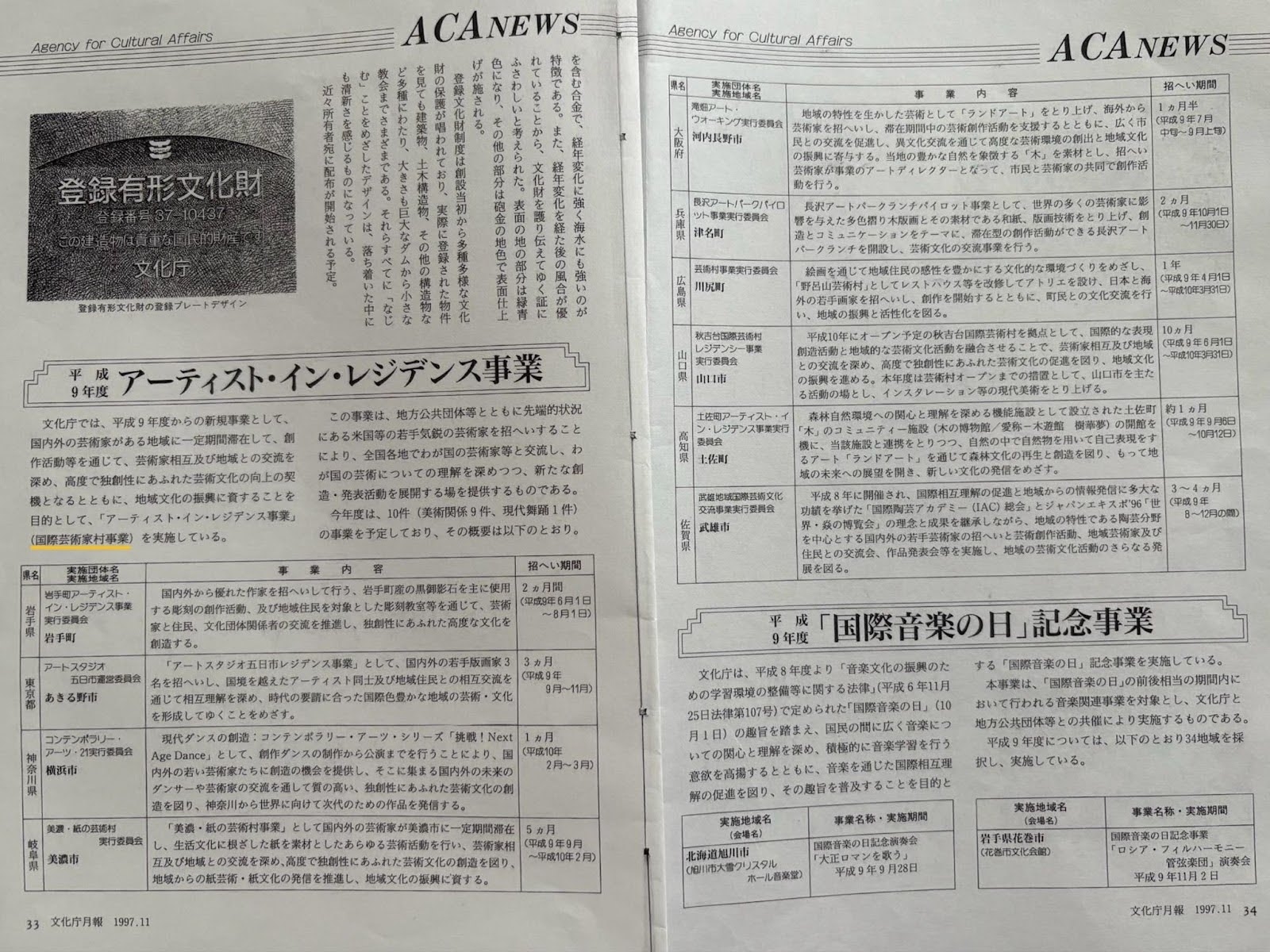

This executive committee format from the dawn of the AIR seems to have served as the prototype for a distinctively Japanese AIR system of residencies firmly grounded in regional revitalization, a feature that persists decades on. At this stage, the “collective” AIRs based on individuals or artist groups found today were virtually non-existent. Interestingly, an Agency for Cultural Affairs bulletin in the first year (Fig. 5) makes reference to an “Artist in Residence Program” (International Artist Village Program). One imagines this was promoted using the term “International Art Village” because the English phrase “artist in residence” was unfamiliar to most Japanese at the time. Echoes of this can be seen in the name of the Akiyoshidai International Art Village, launched in the first year of the program, and still operating today.

Incidentally records show that by the third year, when S-AIR applied, the phrase “International Artist Village Program” was no longer in use, having been replaced by “Culture-Based Community Building Program.”

Fig. 5 Bunkacho Geppo monthly bulletin of the Agency for Cultural Affairs No. 350, November 1997.

Underlined text on line 7 of main text says Kokusai Geijutsuka Mura Jigyo (International Artist Village Program).

Today’s map of artist residencies in Japan, meanwhile, is thoughtfully provided online as part of the AIR_J Japanese artist in residence website (Fig. 6) covering the whole of Japan, launched in 2001 by The Japan Foundation, and administered since 2019 by the Kyoto Art Center. As of July 3, 2025 the database contains 119 Japanese AIR programs, and although only one—the Kamiyama Artist in Residence—still bears the title “executive committee” in Japanese, one suspects there remain many that operate using this format. These days only a portion of AIRs are run solely with Agency for Cultural Affairs assistance, and the great diversity of organizations and operating methods, including government and local authority programs, NPOs, general incorporated associations, companies, foundations, collectives and private individuals has in turn resulted in more diverse naming.

Features of the early Agency for Cultural Affairs AIRs: East-west cultural divide

As the early Agency for Cultural Affairs maps (Figs. 1 and 2) show, there were more AIRs in the west of the country than in the Kanto region, and few in the east. East of Kanto there is just one, in Iwate. This phenomenon can be observed frequently not only in AIRs, but other cultural projects of national scale too. When a new cultural trend emerges, it often seems to take hold first in the west of Japan, then the east after that, somewhat patchily in places like Tohoku and Hokkaido. Doubtless there are various factors involved, such as population density and local economic conditions, but I remember feeling that from the perspective of those in the center, ie the capital, aiming for a nationwide rollout of a cultural program, this must seem unbalanced, so any application we made would have a good chance of success. Living in Hokkaido, the place furthest east in Japan, and its northernmost extremity, I had always sensed this cultural divide between east and west. It was the Agency for Cultural Affairs AIR map, showing regions where the Artist in Residence Program (Fig. 1) had been implemented, that prompted me to submit an application.

Fig. 6 The current AIR_J website (Accessed September 3, 2025). Someone from the Goethe-Institut, the official German cultural institute, once told me how splendid it was to have a one-stop national website for AIRs, and that Germany had nothing like it.

At any rate, the shift from the mere ten locations on that initial Japanese AIR map from the Agency for Cultural Affairs (Fig. 3/1997), to over ten times that number 28 years later (Fig. 6), in part due to an increase in programs without Agency involvement, is like a whole different world. In fact the content of that AIR support is also changing, shifting from the full support model in which the Japan side pays all expenses such as travel and accommodation/living costs, to increasingly—due to some extent to the increase in inbound visitors in recent years—self-funded AIRs in which artists pay their own way; and to a level of support lying between the two, in which the hosts bear just a portion of the cost. In recent years the Tenjinyama Art Studio5 in my home city of Sapporo has apparently been accessed by up to 400 artist visitors annually. Meaning even just in Sapporo, 57 times the initial seven of 1999. One reason for the program’s popularity is that because it is run by the Sapporo municipal authorities, accommodation is very cheap, and apparently there are a lot of self-funded long-term artists in residence.

The impact of growing inbound visitor numbers has been boosted further by a recent boom in international arts festivals around Japan, and as the case above shows, the number of artists in residence has in fact expanded at a rate several times that of the number of programs on offer. So far, unfortunately, I have been unable to source any data on the growth in actual resident numbers in Japan.

(To be continued)1. Artist residency operating in the German city of Bremen since the 18th century. Also known for the poet Rilke spending time there.

2. Artist residency run by the French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs since 1992. Acts as a branch of the Institut Français, and is supported by its main patron the Bettencourt Schueller Foundation, plus the Paris headquarters of the Institut Français.

3. Artist residency with a ceramic art focus, established in 1992 in Shiga Prefecture, renowned home of Shigaraki ware. Located in a park complex with facilities for the creation, study and display of pottery.

4. Artist residency in the city of Moriya in Ibaraki, operated by the Ibaraki International Association. Has been running since 1994, making it a pioneer of the contemporary art AIR in Japan.

5. Artist-in-residence facility run by the city of Sapporo, launched in 2014 following renovation and refitting of the former Sapporo Guest House. Currently operated by general incorporated association AIS Planning.

AIR and Me

Part 1: Sapporo as art studio—since “Ripple Across the Water ’95”

Part 2: Sapporo as art studio—since “Ripple Across the Water ’95”

Shibata Hisashi

Director, NPO S-AIR / AIR Network Japan

Over the 26 years since the Sapporo Artist in Residence (now S-AIR) executive committee era, Shibata has been involved in residencies and research by 106 artists and artist units from 37 countries, also in sending 24 Japanese artists/artist units to residencies in 14 countries. Since 2014 he has been a professor at the Hokkaido University of Education Iwamizawa Campus (Art Project Lab). A member of the executive committee for Res Artis General Meeting 2012 Tokyo, he is actively involved in the AIR Network Japan network of AIR organizations across the country, and in the launch of various art projects and art spaces. Co-author of What will change with the designated manager system? (Suiyosha), Basic research into the promotion of regional culture through art and cultural facilities utilizing abandoned schools (Kyodo Bunkasha), and Artist in Residence – The potential to connect towns, people, and art (Bigaku Shuppan). NPO S-AIR, which he heads, was awarded the Japan Foundation Prize for Global Citizenship in 2008.