Cultural Currency 36, Part 1 “Luigi Ghirri Infinite Landscapes” @ Tokyo Photographic Museum

From theodolite to color—the photographs of Luigi Ghirri

By Shimizu Minoru

©Heirs of Luigi Ghirri

“The two major expressive elements central to a photograph are framing and light.”1

Modernism in photography unfolded around the concept of “reality as it is,” but would be subject to a simplification of sorts during the 1920s courtesy of Surrealism before coming to its full expression over the course of the 1930s alongside the “documentary” approach derived therein. Simplification here refers to the perception of reality being stratified into “ordinary reality (the real)” and “reality as it is (the surreal),” the latent latter within the former being laid bare by the actions of the artist. Rosalind Krauss referred to the presumption of another reality existing beneath the skin of or behind reality as accounting for “the incredible coherence of European photography of this period,”2 and whether in “Das Optisch-Unbewußte (The Optical Unconscious)” of Walter Benjamin, or Pierre Mac Orlan’s “le fantastique social (the social uncanny),” the question of this hidden dimension is precisely that addressed by interwar photographic discourse. This dual-layer theory dominated the photography world for around 60 years, coming to encompass—in the book that could be said to encapsulate it: 1980’s Camera Lucida by Roland Barthes—the duality of studium (the ordinary dimension of a photograph) and punctum (the hidden dimension that manifests in the fine details of a photograph, and “pierces” or “pricks” the viewer). In this theory of photography, the mission of the artist was not to overwrite the maker’s subjective expression of reality, but to expose in all its rawness the unadorned “as it is” state concealed by the hazy human gaze (ie the way our views are colored by bias), in other words to clean, bleach, remove those fogged-up “colored glasses.” The inversion by which black-and-white photographs came to claim “as it is” status occurred because purifying reduction to “as it is” did not take on board the—painterly, subjective, changeable—element that is color.

It is widely acknowledged that color was only properly accepted in photographic expression from the mid-1970s onward. William Eggleston’s Guide3 published by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and deemed to be the first example, appeared in 1976 (covering works produced from 1969–71), with Cape Light4 by Joel Meyerowitz of “new color” fame being published in 1978. But not even these photographs can escape that dual-layered construct. William Eggleston uses the dye-transfer technique5 to color quotidian everyday scenes in order to highlight the “grotesque” (Sherwood Anderson, Winesburg, Ohio6) lurking therein. Meyerowitz’s landscape photographs, distinguished by the leisurely light absorption of long exposure, were expressions of natural beauty overlooked by the human eye and only revealed by photography, and of the aura of the places in question.

Yet during this period there was another color photographer, in Italy. In contemporary Japanese terms, the photographs of Luigi Ghirri (1943–1992), starting with Kodachrome (1978, shot from 1970–78), can be viewed as distant antecedents of practitioners such as Kido Tamotsu and Kano Shunsuke. The dual-layer theory of photography no longer applies here; rather we are dealing with a throwback to Alfred Stieglitz’s exploration of an “essence of photography” predating the simplification occasioned by Surrealism, and forgotten in the shadow of the straightforward dual-layer theory.

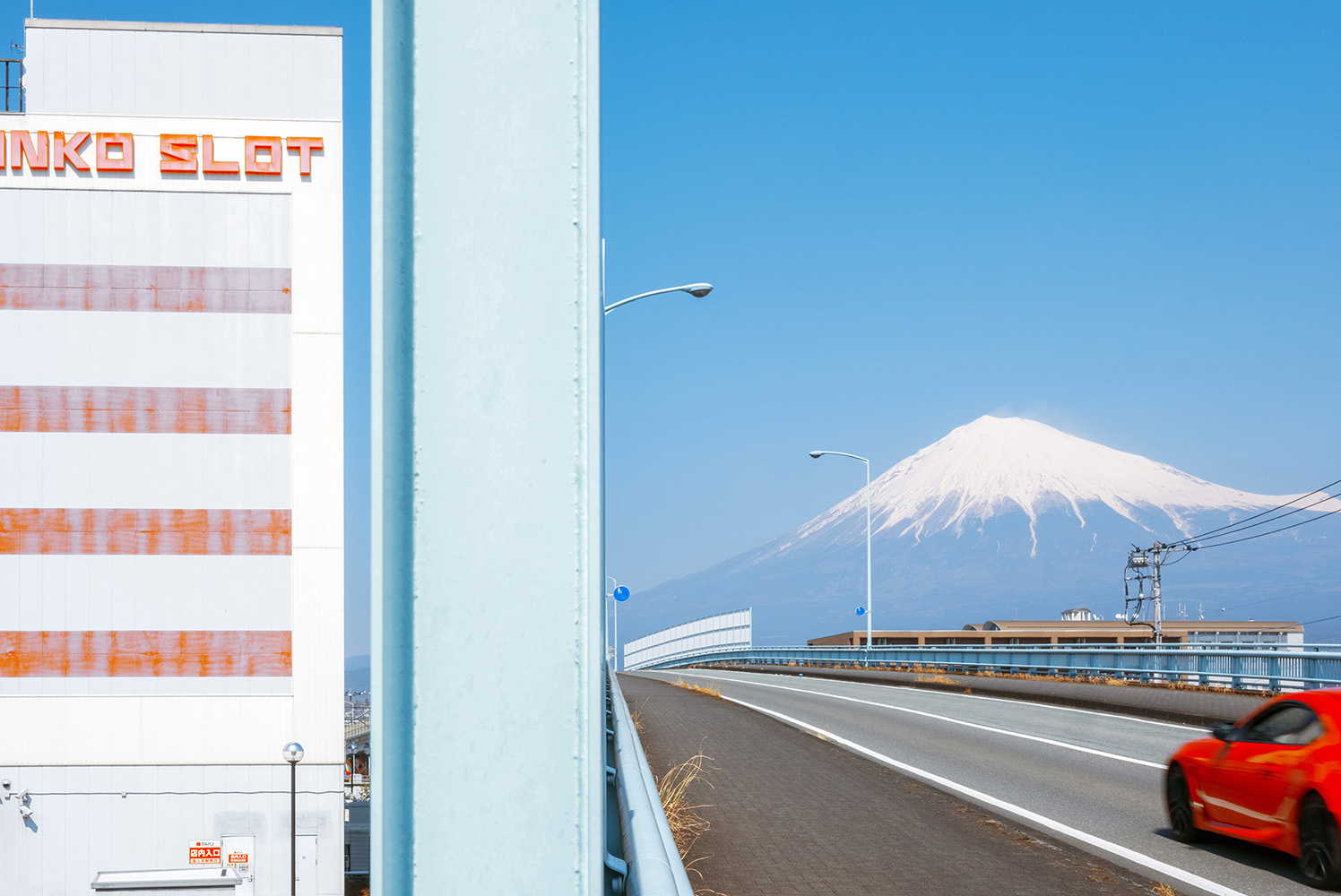

Kano Shunsuke, spacious notion_17, 2015

Kido Tamotsu, Red Car, 2025

Stieglitz’s inquiries into the “essence of photography” occurred under the influence of the concurrent collage of Picasso and Braque, and readymades of Duchamp. That is to say, they were photographic reinterpretations of collage and readymade. With regard to the latter, photography captures the world existing there anyway, so photographs can only ever be readymade. The collages referred to here were layered collage, a process in which layers were superimposed on one another, repeatedly updating the hierarchy among them. Layer here refers to the basal plane on which the images on the picture plane sit, so the process of updating means not finalizing the image on the picture plane as a single entity, but rather maintaining a state of multiplicity (the coexistence of multiple perspectives and meanings).

In order to achieve that photographic multiplicity, Stieglitz initially combined the subject with associated objects, or gathered multiple objects in front of the camera, before eventually coming to the realization that if the realm of the readymade is framed in a suitable manner, the world will manifest as a multilayered collage. Meaning that the essence of photography lies in framing. In the 1920s Stieglitz produced the “Equivalent” series of photographs in which this essence arises solely from framing, and in his final years he went on to photograph skyscraper-crammed cityscapes as collages in which light and shadow shift incessantly.7

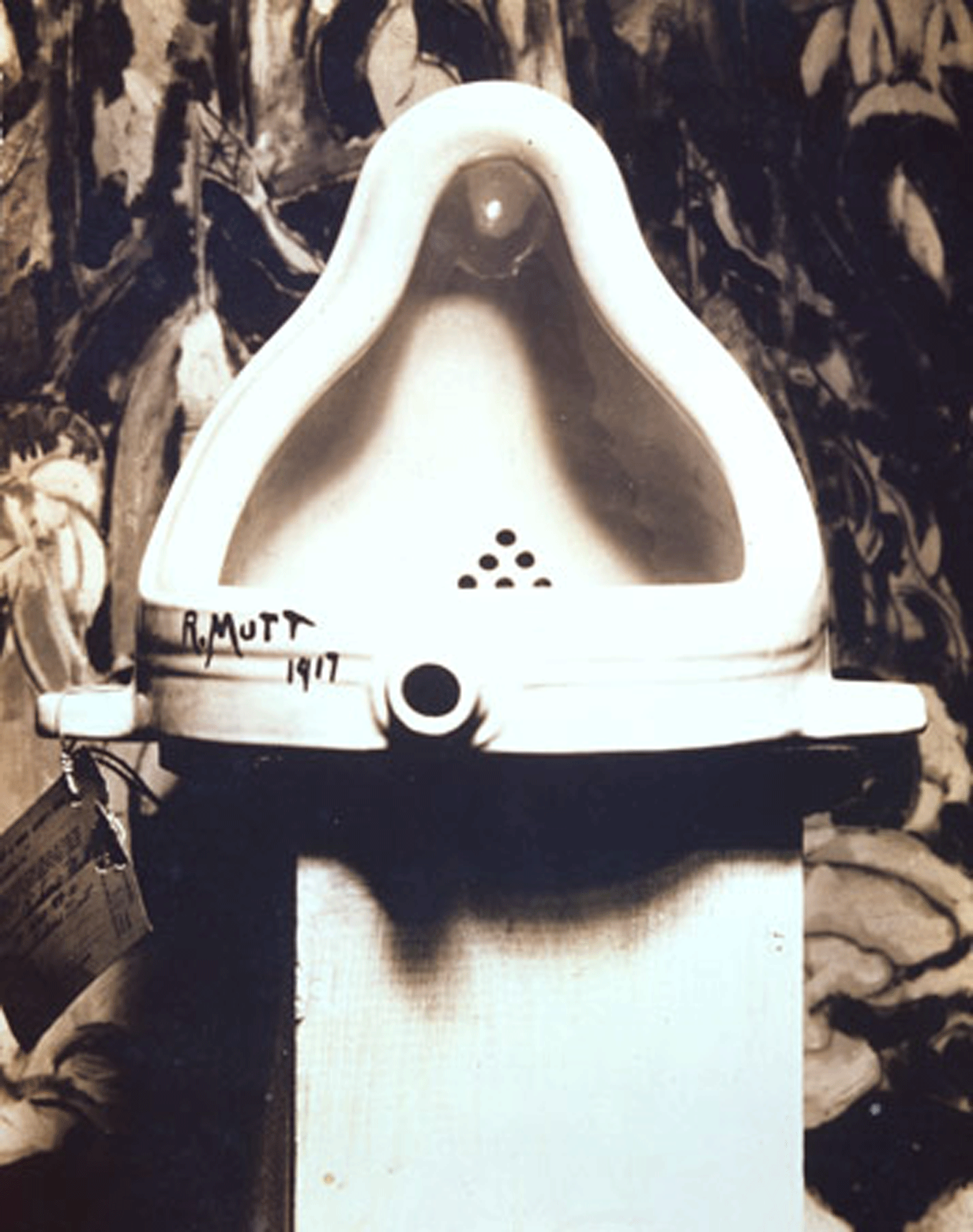

Alfred Stieglitz, photograph of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, 1917. © Jacqueline Matisse Monnier / MoMA:

Duchamp’s Fountain on a stand, combined with Marsden Hartley’s The Warriors (1913) as background, the implication being that Duchamp is a warrior of the avant-garde.

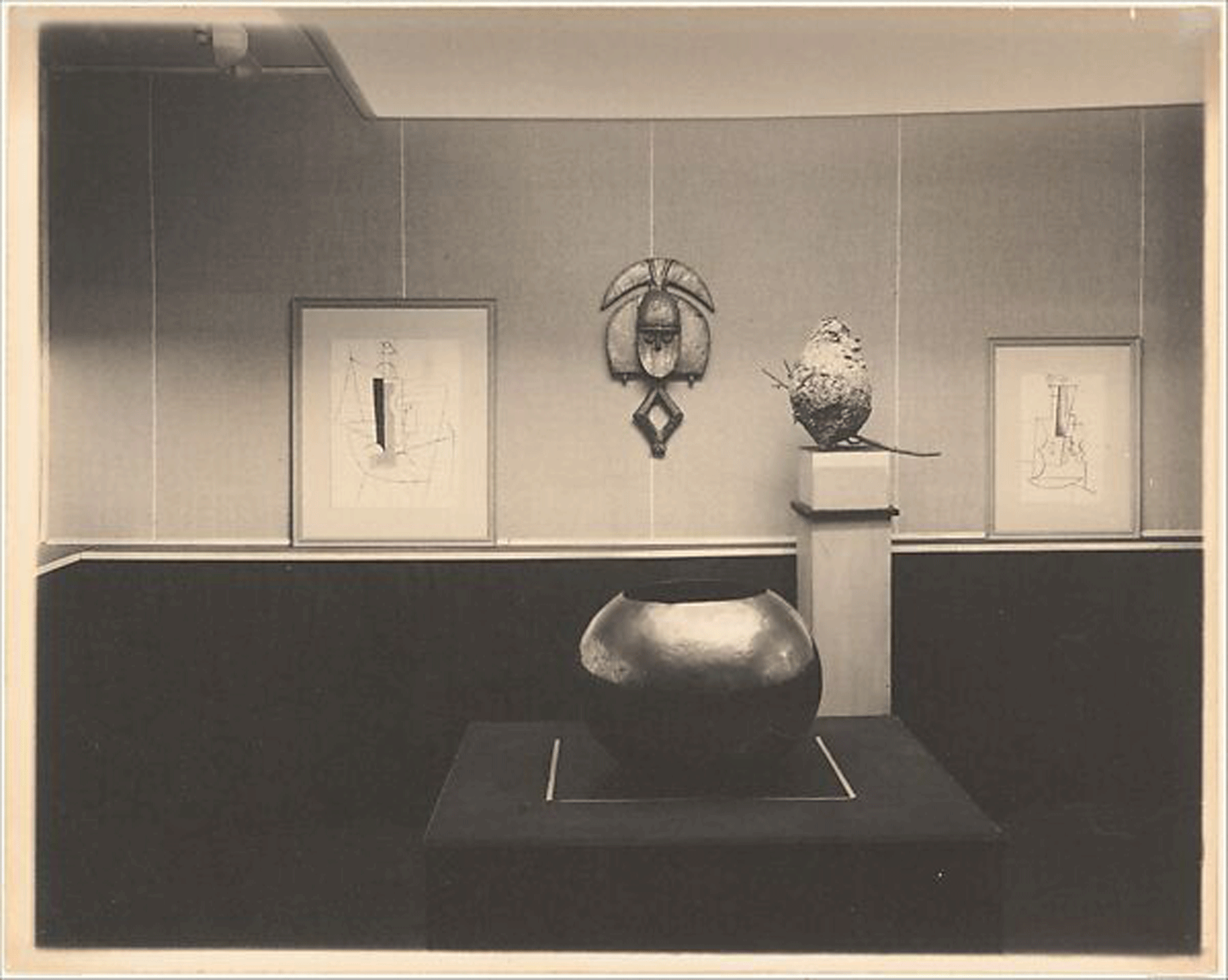

Alfred Stieglitz, 291 Picasso Braque Exhibition (1915): This is not a photo of an actual exhibition, but an African mask, wasp’s nest, and metal bowl purposely brought together with collages by Picasso and Braque.

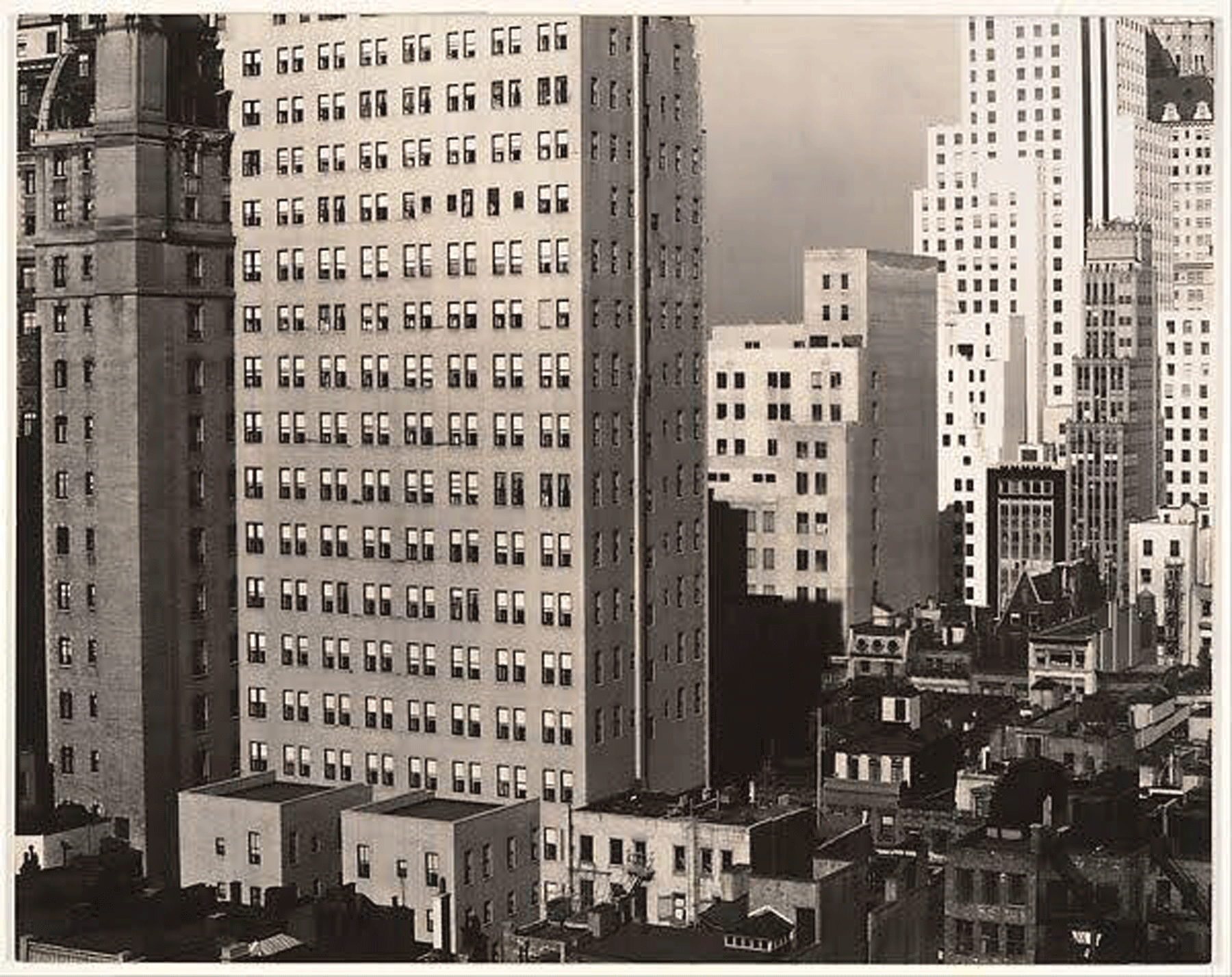

Alfred Stieglitz, From my Window at the Shelton, North (1931):

Blocks of various sizes and grayscales overlap in a city scene.

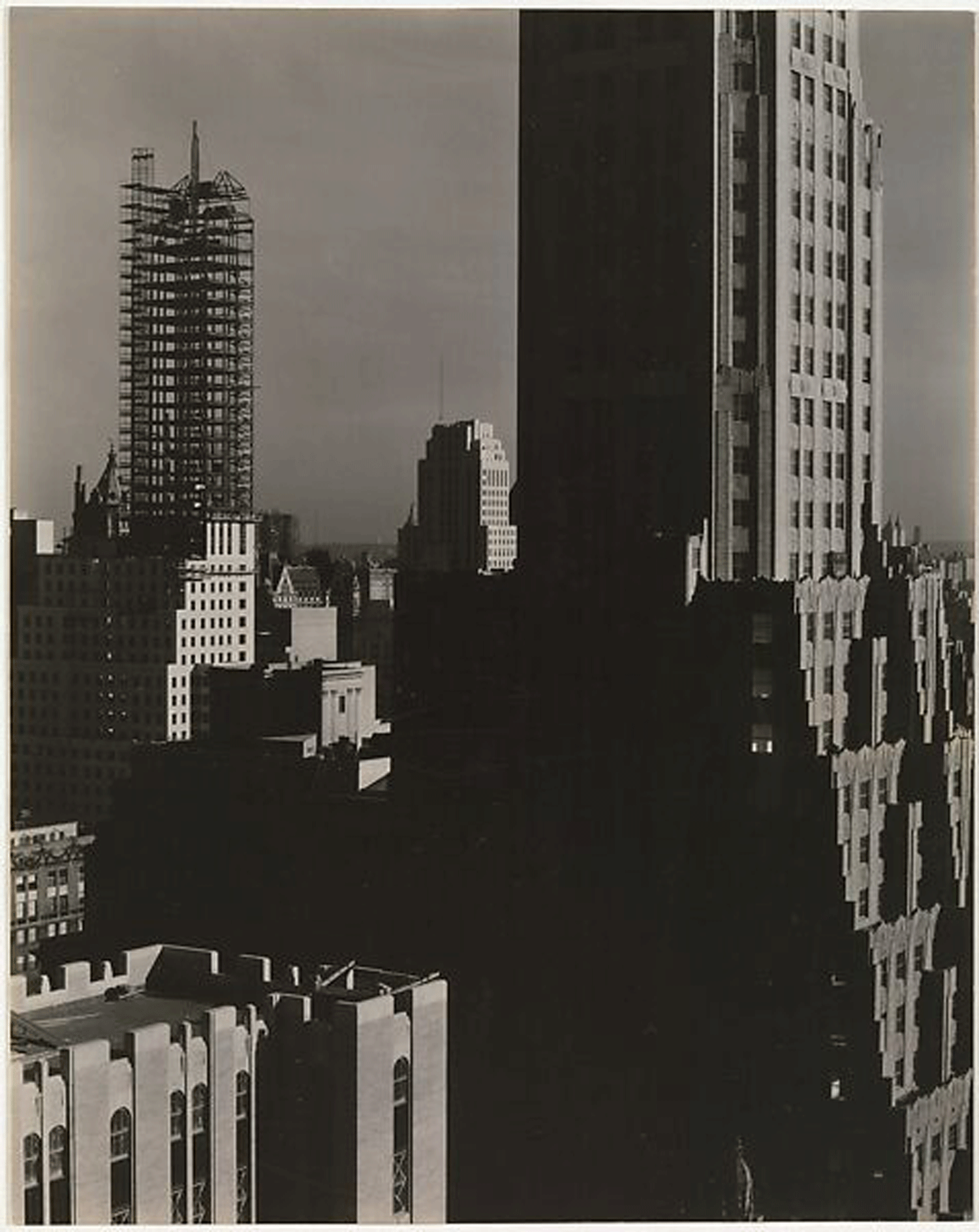

Alfred Stieglitz, From my Window at the Shelton, North (1931):

A high-rise under construction at the back left hints at the passing of time. The time of day turns shadows into giant color fields amid a collage of blocks.

1. Luigi Ghirri, Shashin kōgi [Photography lectures], trans. Kanno Yumi (Misuzu Shobo, 2014), 163.

2. Rosalind Krauss, “The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism” October 19 (Winter 1981), 34.

3. Catalogue for William Eggleston’s solo exhibition “Photographs by William Eggleston” held at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1976. The exhibition was MoMA’s first solo exhibition of color photography, and this was the first color photography book published by MoMA. The exhibition was curated and the catalogue edited by John Szarkowski, then director of the museum. (Editor’s note)

4. Iconic photobook by Joel Meyerowitz. Interrogating the meaning of light, format and theme in the medium of photography, Meyerowitz carved out new territory in color photography.

5. Dye-transfer printing is a photographic printing process developed by Kodak in the 1940s. Color photographs are broken down into the three primary shades of C (cyan), M (magenta) and Y (yellow), and dye transferred onto separate supports known as matrices with a relief image in each color, to generate the image. The process was distinguished by its superlative color development and durability. Eggleston employed this commercial technique in his work. (Editor’s note)

6. Winesburg, Ohio (1919) is a collection of 22 short stories by Sherwood Anderson. In one of these stories, “The Book of the Grotesque,” Anderson writes of how when a person fixates on one particular aspect of themselves, despite humans inherently having many sides, they become distorted, or “grotesque.” (Editor’s note)

7. The contrast between assemblage and straight collage also appears in the work of Walker Evans. An example of the former, found in American Photographs, is “Interior Detail, West Virginia Coal Miner’s House, 1935,” an assemblage of broom, cane chair, Coca-Cola poster, and cut-out from celebratory graduation poster. An example of the latter is “Gas Station, Reedsville, West Virginia, 1936,” a collage of sky, circular sign, white sign (back), a virtual oblong formed by the lower edge of the white sign and the rectangle of the building, ground, and telegraph pole bisecting the picture plane.

(All accessed September 23, 2025).

“Luigi Ghirri Infinite Landscapes” Tokyo Photographic Museum

July 3–September 28, 2025

Shimizu Minoru

Art critic. Professor, Faculty of Global and Regional Studies, Doshisha University. Regularly contributes essays and critics for art/photography books, magazines and museum catalogues including those of Daido Moriyama, Gerhard Richter, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Wolfgang Tillmans and other Japanese and international artists.

Selected publications: “The Art of Equivalence” in Wolfgang Tillmans, truth study center (Taschen, 2005); “Shinjuku, Index” in Daido Moriyama (Editorial RM, 2007); “Fiction and Restoration of Eternity” in Hiroshi Sugimoto: Nature of Light (Izu Photo Museum/Nohara, 2009); “Daido Moriyama’s Farewell Photography” in Daido Moriyama (Tate Modern, 2012); “Guardian of the Void” in Palais no. 19 (Palais de Tokyo, Paris), 2014; “Post-Provoke et Post-Conpora: La photographie Japonaise depuis les années 1970” (Pompidou Metz, 2017).