Cultural Currency 36, Part 2 “Luigi Ghirri Infinite Landscapes” @ Tokyo Photographic Museum

From theodolite to color—the photographs of Luigi Ghirri

By Shimizu Minoru

©Heirs of Luigi Ghirri

The quote from Ghirri at the start of Part 1 leads us to the photographs of Stieglitz, Evans et al from before the advent of the dual-layer construct of realism/documentary; that is, to collage-like expression of the world by framing. The photographer no longer reveals layers of truth concealed in the world, but merely frames literally just the world existing there, that world appearing “as it is,” in all its multiplicity (what Ghirri calls foto-smontaggio). “As it is” is neither purity nor truth, but the inability to see the full view, to identify sameness, the enacting of multicausal determination.

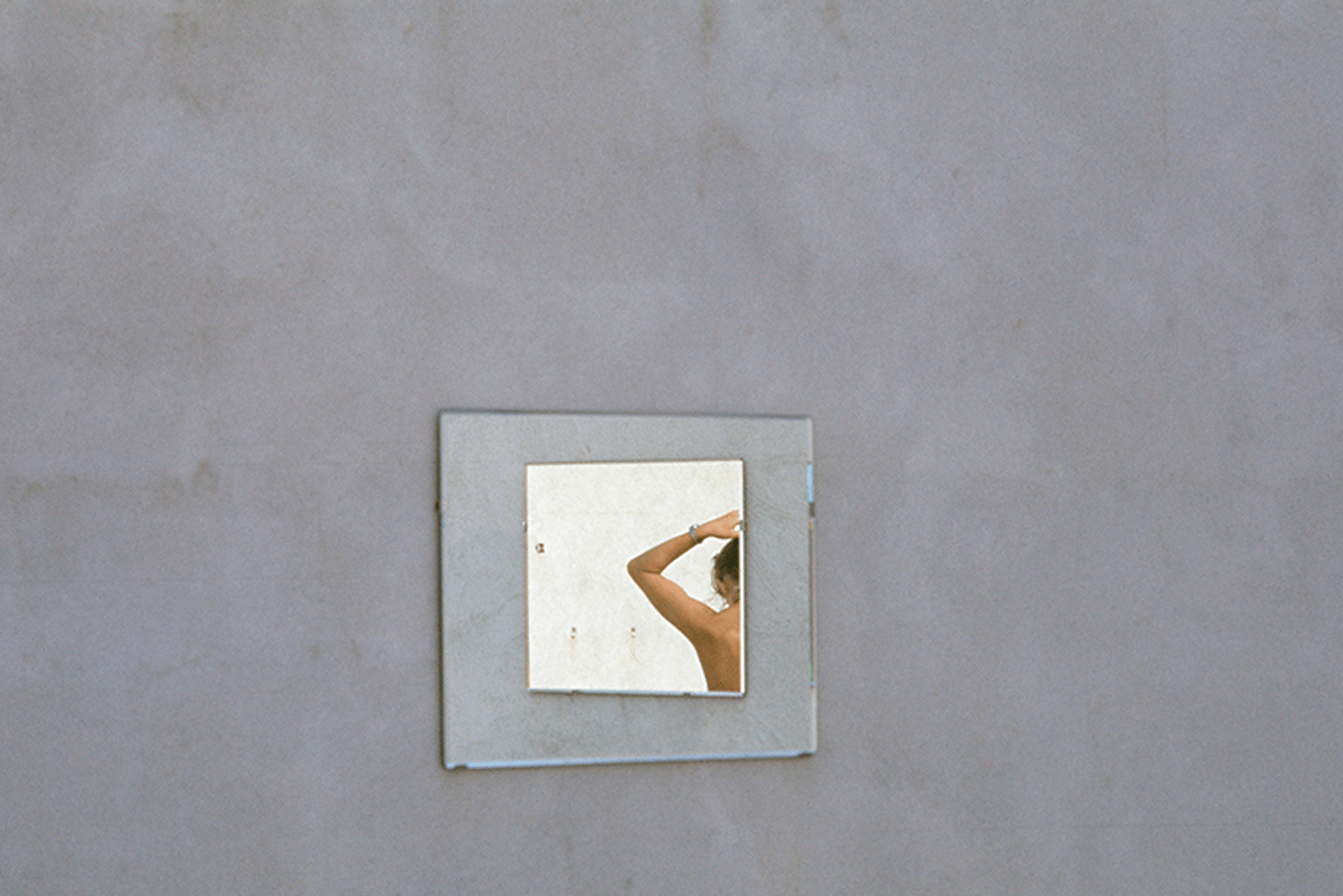

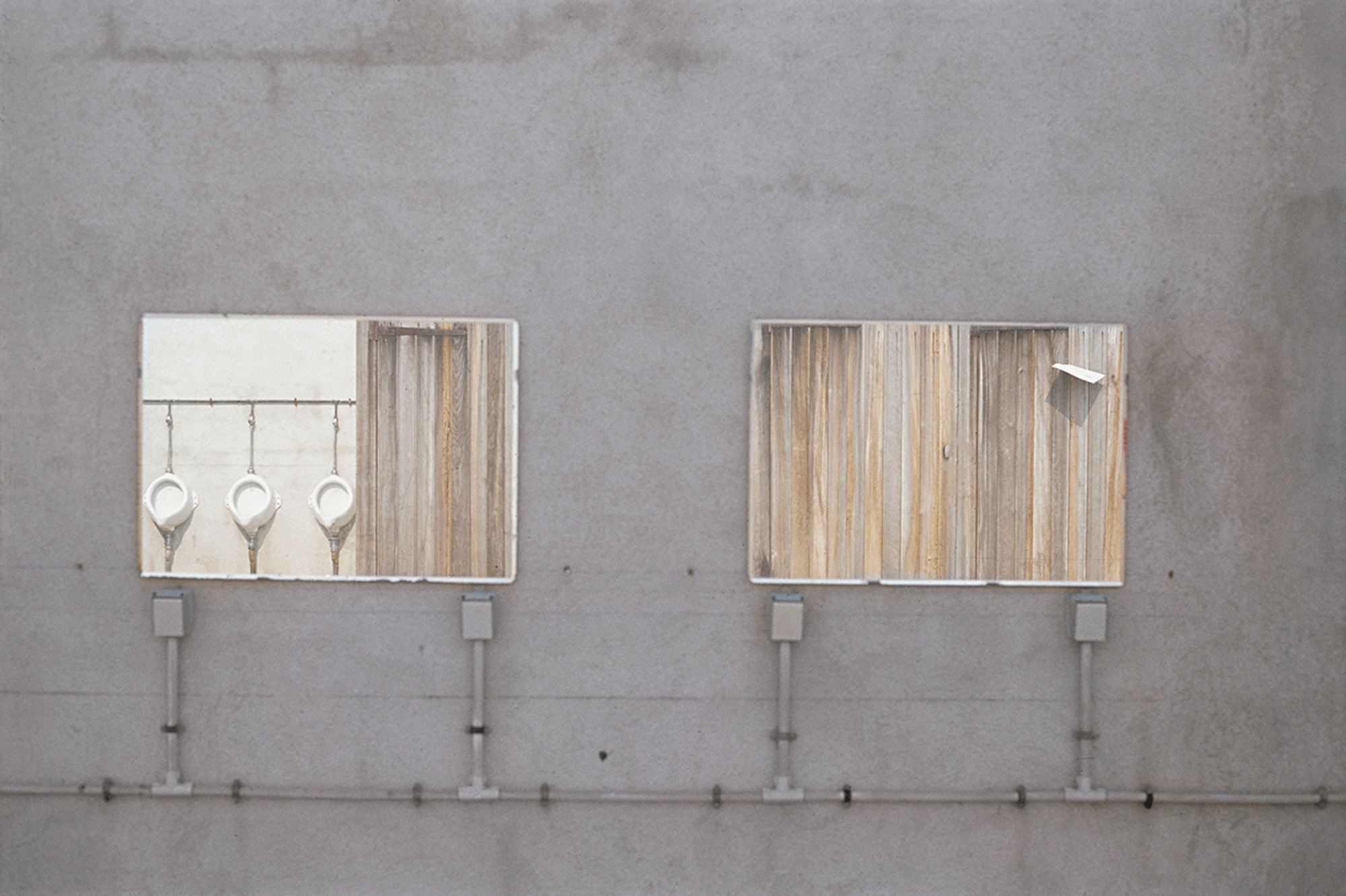

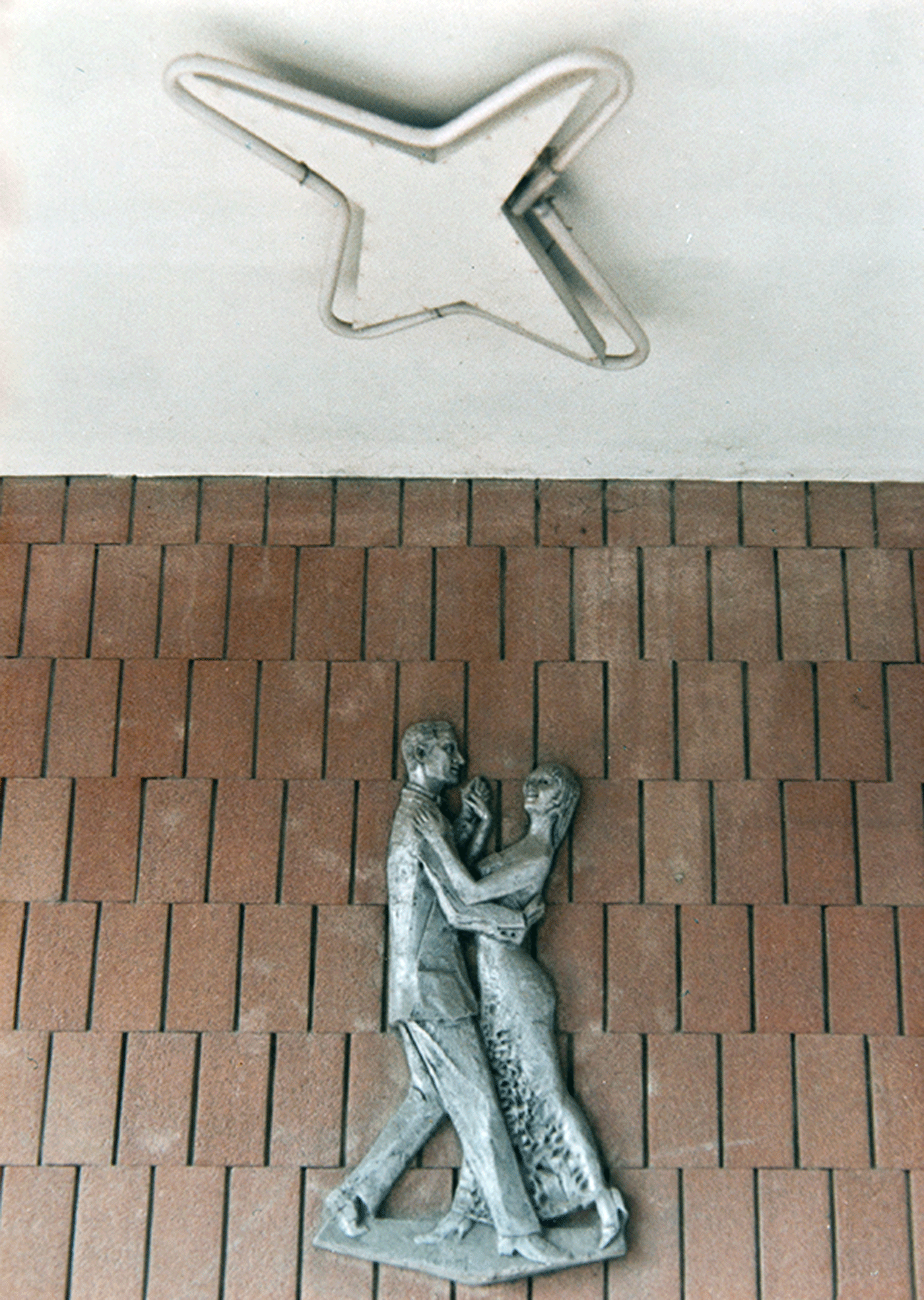

Rectangles various (mirrors, color fields, windows, glass) superimposed on landscapes, landscape pictures, posters, wallpaper, maps; shadows, rear views, and objects of different sorts. Landscapes in which horizons on water and land, gates, stone walls, pillars, window frames serve as diverse thresholds, creating boundaries. Here we have realms manifesting as collage via suitable framing, that Ghirri would probably call “landscapes” or “still lifes” rather than “equivalents.” These realms are composed of multiple layers, and defy unambiguous identification of their subject. In a single image various formal frames (rectangles) and frames of meaning (subject) combine, both rectangles and subjects as printed images that once shot, could be mistaken for the genuine article (figs. 1, 2), or reflections in glass or mirror. In addition, because each individual frame is frequently a fragment, even the area outside the frame (or in the case of mirrors, the front side), not visible in the picture plane is included therein.

Thus appearing in Ghirri’s photographs are “as it is” worlds in which the more we look, the less we understand what the photographer has photographed, and how (exactly like the works of Kano and Kido). Faced with the multiplicity of the realm presented, the viewer will doubtless find niggling questions beginning to form. How are the photographer and subject positioned in relation to one another? (Fig. 3) Why is the photographer not reflected in a mirror with which he is presumably aligned (the rectangle of the mirror is not distorted)? (Fig. 4). Why, rather, does part of the mirror appear to have peeled off (was it not a mirror but wallpaper?) (Fig. 5) Why do walls presumably intersecting at right angles appear as a single flat surface? (Figs. 6, 7). And so on and so forth. Did the photographer move the front and/or rear standards in his view camera? Ghirri died young, at just 49, so we will never know the answers. In any case, the key to solving these riddles lies in the angle connecting camera and subject. For a surveyor theodolite is a vital tool for measuring angles and checking levelness. Perhaps the photographs of Ghirri, a former surveyor, were unorthodox theodolite shots, as it were, captured by shifting the angle between camera and subject off the horizontal.

Fig. 1. Luigi Ghirri, Modena, 1973, from the series “Kodachrome”

All photos: ©Heirs of Luigi Ghirri

Fig. 2. Luigi Ghirri, Engelberg, 1972, from the series “Kodachrome”

Fig. 3. Luigi Ghirri, Ile Rousse, 1976, from the series “Kodachrome”

Fig. 4. Luigi Ghirri, Marina di Ravenna, 1970, from the series “Kodachrome”

Fig. 5. Luigi Ghirri, Ile Rousse, 1976, from the series “Kodachrome”

Fig. 6. Luigi Ghirri, Modena, 1971, from the series “Photographs from my Early Years”

Fig. 7. Luigi Ghirri, Ile Rousse, 1976, from the series “Kodachrome”

So, “The two major expressive elements central to a photograph are framing and light,” apparently. “Framing” manifests as theodolite shots designed to deviate from the horizontal; as collage photos using various frames (rectangles). Though the tricky photos mentioned earlier recede, this characteristic can also be detected in Ghirri’s later works. So what about “light”? Saying that the essence of photography as optical equipment is light, is simply stating the obvious. The “light” referred to here is most likely color. And the photographs taken by Ghirri over not much more than two decades seem to have gradually shifted their gravitational center from photographs distinguished by theodolite-adjacent angles, to the exploration of color: “the landscape of Italy.”

Natural or manmade, Ghirri’s Italian landscapes are bright yet brim with low saturation tones; slightly faded neutrals—off-white, beige, amber, pale blue… Important to remember here is that Italy has no “nature” in the truest sense. Nature cultivated, used by humans since prehistoric times, its very DNA modified, thoroughly tamed, is nature that has become half human. On the other hand, compared to Dubai, say, or the newest urban landscapes of China, Italian cities with their plethora of traditional architecture dating back as far as the Romans, cannot be termed purely “manmade” either. The cities of Italy, exposed to light and weather over centuries, are a manmade that has grown semi-natural. This is also different to the way that American or Japanese suburbia, for example, constitutes neither nature nor city. In Italy, a land where neither pure nature nor pure manmade exist, the dichotomy of “nature” and “manmade” vanishes. The slightly tired-looking, off-tone coloring was the palette Ghirri chose for an Italian landscape marked by a multifarious mix of natural and artificial.

“Luigi Ghirri Infinite Landscapes”

Tokyo Photographic Museum

July 3–September 28, 2025

Shimizu Minoru

Art critic. Professor, Faculty of Global and Regional Studies, Doshisha University. Regularly contributes essays and critics for art/photography books, magazines and museum catalogues including those of Daido Moriyama, Gerhard Richter, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Wolfgang Tillmans and other Japanese and international artists.

Selected publications: “The Art of Equivalence” in Wolfgang Tillmans, truth study center (Taschen, 2005); “Shinjuku, Index” in Daido Moriyama (Editorial RM, 2007); “Fiction and Restoration of Eternity” in Hiroshi Sugimoto: Nature of Light (Izu Photo Museum/Nohara, 2009); “Daido Moriyama’s Farewell Photography” in Daido Moriyama (Tate Modern, 2012); “Guardian of the Void” in Palais no. 19 (Palais de Tokyo, Paris), 2014; “Post-Provoke et Post-Conpora: La photographie Japonaise depuis les années 1970” (Pompidou Metz, 2017).