Out of Kyoto

002 Viewing Brancusi in Romania

By Ozaki Tetsuya

Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957) was born into a farming family in the village of Hobiţa, Gorj, in the Oltenia region in the southwest of Romania. These days there are fears of deforestation and drought on this south side of the Carpathians, but originally the region was a rich source of high-quality timber, and places named for trees or for industries like charcoal burning, can still be found here and there. Brancusi’s peasant grandfather was also a woodcutter, and a talented carpenter.1

Brancusi’s childhood home in Hobiţa was lost in a fire, but recreated on the same site, and serves as a museum.

A bronze of Brancusi by pupil Milița Petrașcu.

Asked to make a monument for the city of Târgu Jiu, Petrașcu firmly declined and instead recommended his former mentor.

The young Brancusi ran away from home on numerous occasions, fleeing to the county capital of Târgu Jiu more than once only to be retrieved by his mother. At the age of thirteen he finally made it as far as Craiova, capital of the adjacent county of Dolj, where he found work in a public house. Some years later, to the amazement of those around, he used scraps of wood he had found to craft a splendid violin. In 1894 Brancusi’s employer and some regular patrons of the public house sponsored him to study sculpture at the Craiova School of Arts and Crafts. Unsurprisingly the violin no longer exists, but a number of his works from this period can be found on display at the Craiova Art Museum.

In 1898 Brancusi enrolled in the national school of fine arts in the capital Bucharest. After graduating, following a brief stretch of military service and time in Craiova he set off for Paris, on foot (!) apart from the last section of the journey, completed by train. In the French capital he encountered Auguste Rodin, but declaring that “nothing could grow in the shade of a tall tree,” eventually parted ways with Rodin and went on to revolutionize sculpture in his own fashion through the pursuit of “essence.” Brancusi trained Isamu Noguchi, and his influence on subsequent artists from Carl Andre to Antony Gormley, needs no elaboration. The year before he died, Brancusi gifted his entire workspace to the French government, including unfinished works and furniture, on the condition that after his death it be restored to how it was when he was alive. Many readers will have seen the reconstructed studio by Renzo Piano at the Pompidou Center, which in 2024 also hosted the largest-ever Brancusi retrospective.

Very sorry to miss this major exhibition, at the end of summer I traveled instead to Romania, to see works by the master that still remain in his homeland. After all, as Theodor Adorno opined,2 art museums are basically mausoleums (if that sounds like sour grapes, it’s because it is). My primary focus on the trip was Brancusi’s outdoor sculptures, in particular Endless Column.

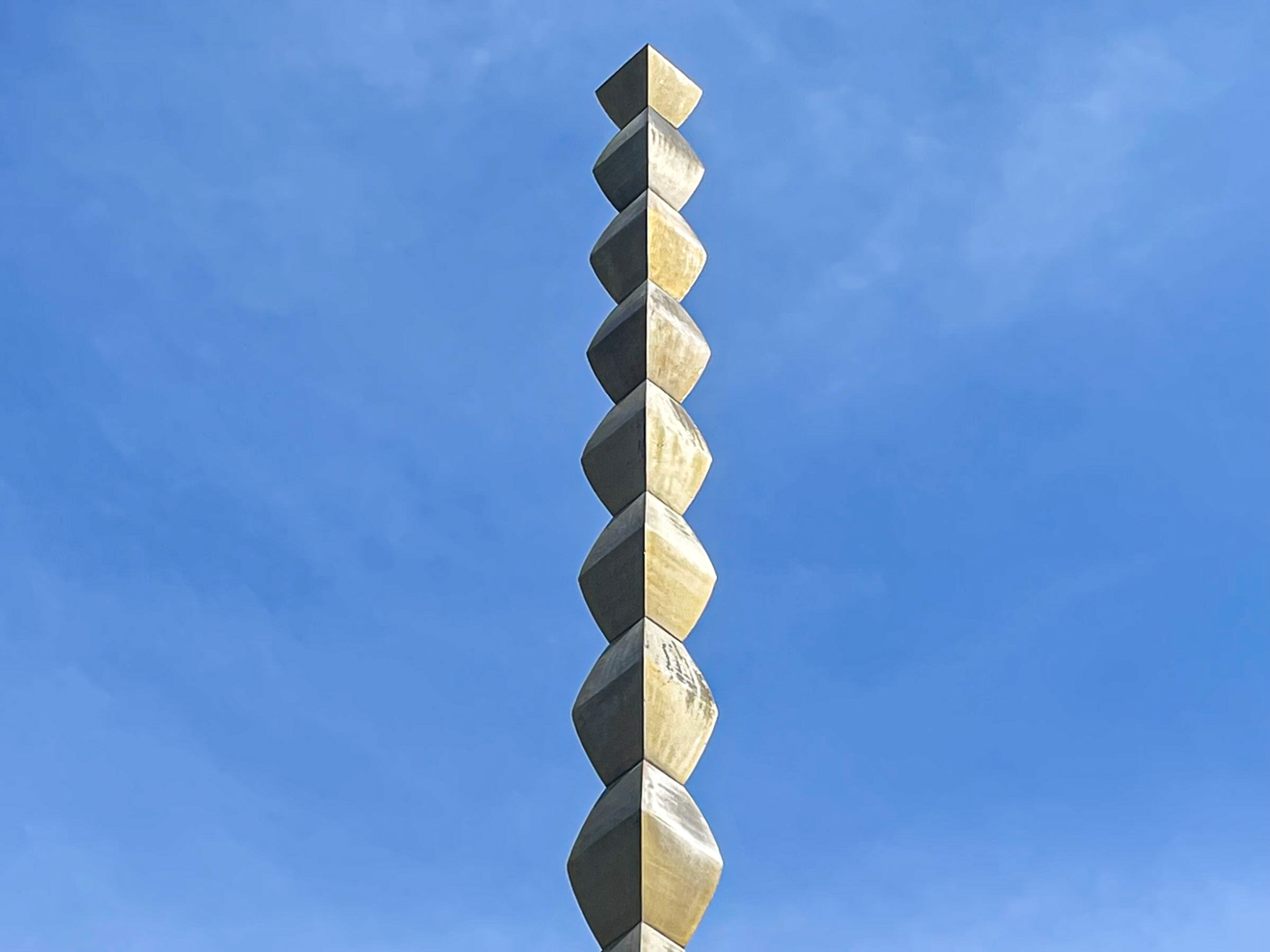

Constantin Brancusi, Endless Column (1937–38)

The Brancuși Monumental Ensemble of Târgu Jiu, which includes Endless Column, was conceived in the late 1930s to honor, remember and pray for the repose of local soldiers who died in the First World War. Three works are positioned on an axis extending 1.5 kilometers almost due east from the Jiu River, which flows through the center of the city.3 The Table of Silence, situated in a public park at the western end, consists of a round table just over two meters in diameter, and 12 round hour-glass shaped seats. The Gate of the Kiss in the same park is an imposing portal 5.2 meters high and 6.6 meters wide. It also includes a number of seats and benches designed by Brancusi, all hewn from limestone.

The Gate of the Kiss, with The Table of Silence visible in the rear.

The Table of Silence (1937) with view of the Carpathians beyond the Jiu River.

Right in the middle of the axis, known as the Avenue of Heroes, is a Romanian Orthodox church, and at the eastern end, in another, slightly elevated park, the almost 30-meter Endless Column. As noted by writer and historian Mircea Eliade, the column stretches straight up toward the heavens from one end of a horizontal axis, as the vertical axis of the world (axis mundi).4 Needless to say Andre too described the column as continuing “beyond its earthbound limit” and also driving into the earth.5 This column holding up the firmament is none other than the World Tree of multiple mythologies, obviously also supporting the earth. The rhomboidal steel modules that comprise the work are half-size just at its base and tip. Perhaps, having thought hard about the relationship between sculpture and plinth, the artist designed these half-modules to look like the roots/base of the World Tree, supporting both heaven and earth.

Pillar from the artist’s recreated home

Pillar from a home in 19th-century Oltenia (photo taken at the Museum of Oltenia)

Brancusi produced series such as Miastra and Bird in Space in seeming response to Duchamp’s provocation to “do anything better than a propeller,” but indispensable to the theme of flight common to these and Endless Column, alongside the heavens as arrival point, is the earth as departure point. Note too that when heroes are buried and the subsequent feasting is over, they cross the boundary between this world and the next, heading high into the sky. But while their spirit is sent to the heavens, their earthly remains, remain beneath the earth.6 Endless Column is both Jacob’s Ladder, and grave marker.

My visit coincided with the “blood moon” of a total lunar eclipse.

This group of monuments was commissioned by the wartime National Liberal Party administration. Artworks born out of political circumstances—in fact even those that are not—are vulnerable to changing political conditions. Endless Column twice came close to being dismantled during the 1950s under Romania’s Communist regime. The first occasion was in 1951 when the people’s council in Târgu Jiu sought permission from the state to demolish this “metal column with no aesthetic value, embedded in concrete foundations.” The city needed material from Brancusi’s sculpture for its infrastructure.

On this occasion the Romanian Academy wisely rejected the city’s application, but then the sculpture was placed at risk for a second time, in 1953, when the Communist youth organization tried to wrench Endless Column from the ground in order to sell it for scrap and fund their trip to the World Youth Festival. However the party was unable to source high-performance Russian heavy machinery for the job, and locally made tractors failed to budge Brancusi’s creation.7

Having thus somehow survived, Endless Column was added to a list of cultural monuments in 1955, and minor repairs carried out in 1965–66 and again in 1976.8 During these years Nicolae Ceaușescu, appointed general secretary of the Communist Party in 1965 (and executed in 1989), was permitting some limited freedom of expression. Even so, in 1972 sculptor William Tucker painted a bleak picture of the column, noting “The original bright gilt finish has tarnished to the colour of dark bronze or wood,” “One’s first impression of the Column in its own area is that it is neglected and unwanted,” and “The sculpture has the air of being rarely visited.”9

In 1998, a decision was made by the Romanian government and World Monuments Fund to restore the entire Ensemble, and the project was completed in 2000 with financial assistance from the WMF and World Bank. The Table of Silence was moved to beside the Jiu River, the fence surrounding the work removed, the graffiti cleaned off the table and The Gate of the Kiss, new grass and vegetation planted at the park, footpaths re-laid, and the modules of Endless Column repainted to a color close to the original, following repairs.10 Perhaps in recognition of these efforts, in 2024 the Ensemble was assigned World Heritage status.

Installing a work in a place with a link to its maker, giving it a theme related to both maker and location, and motif with its origins in the life of the maker, and history of the place, is a concept that speaks of great depth, and many layers. After decades at the mercy of the times, the reputation of the Ensemble in Târgu Jiu is now well established, and local residents carefully maintain the sculptures. When I was there, the modules of Endless Column had once again begun to fade, but several bridal couples were visiting the sculpture. Perhaps this is what public art should be like, ideally; antithesis of the globally ubiquitous “LOVEs” and “Mamans.”

Come to think of it, I recently spotted someone describing the “Ring” at the Osaka Expo as art. Shaped like a giant roulette wheel, it serves as the perfect celebration of the casino in which history itself will be shaped. It also likely draws on the Japanese flag, or perhaps the logo of the Japan Innovation Party. No? You don’t think so?11

1. The biographical facts cited here rely largely on Nakahara Yusuke’s excellent Brancusi (1986). For the “Ensemble” I referred to the discussion by Sidney Geist (“Brancusi: The Centrality of the Gate,” Artforum, October 1973), and an essay by the daughter of Stefan Georgescu-Gorjan, who assisted in the making of Endless Column (Sorana Georgescu-Gorjan, The wonderful story of the endless column, 1995).

2. “Museums are like the family sepulchres of works of art” (“Valery Proust Museum,” (1953) in Prisms, trans. Samuel and Shierry Weber (Neville Spearman, 1967), 175.

3. About 30 meters beyond Endless Column there was once a circular stone table known as the “Festive Table” or “Last Table.” Nakahara, who visited the site in 1971 and 1985, asserted that the “Festive Table” should be added to the Ensemble, “because overall, in number, four can be seen” (Brancusi, p. 176). Installation of The Table of Silence about 30 meters from The Gate of the Kiss suggests a certain devotion to symmetry, so one does want to agree with Nakahara. However research by Ion Mocioi (Brâncuşi: Ansamblul Monumental “Calea Eroilor” Târgu-Jiu, 2002) has revealed that a gardener at the park made the arbitrary decision to install the table. Due in part to the artist’s own instructions being unknown, the table has been moved to the outer courtyard of the Constantin Brancusi National Museum that opened in 2020.

4. Mircea Eliade, “Brancusi and Mythology” (1907), in Symbolism, the Sacred, and the Arts, ed. Diane Apostolos-Cappadona (Crossroad, 1986).

5. Diane Waldman, Carl Andre (Soloman R. Guggenheim Museum, 1970), 9.

6. One could also superimpose the Last Supper, Stations of the Cross, Crucifixion and Resurrection of Christ.

7. Alin Ion, “Omul care a încercat să dărâme Coloana lui Brâncuşi,” Theologhia, November 25, 2009.

8. Dragos Gheorghiu, “Brancusi’s sculptural ensemble: from Târgu Jiu and its reception in time,” ARKEOS – Perspectivas em Diálogo 57 (2024).

9. William Tucker, “Brancusi at Turgu Jiu,” Studio International 184, no. 948, (October 1972): 117.

10. Richard Newton, Reclaiming Sacred Space, 2006

11. Congratulating myself on coming up with a cool end to my story, I found the inimitable Dave Spector had beaten me to it.

(All accessed October 20, 2025)

About the series

In “Out of Kyoto” writer and art producer Ozaki Tetsuya covers topical issues in the arts and wider culture, exploring the state of artistic expression today, from an historically-informed perspective.

Ozaki Tetsuya

Writer/arts producer. Launched the online culture magazine REALTOKYO in 2000, and the contemporary art magazine ART iT in 2003. General producer of the performing arts program for Aichi Triennale 2013. Served from September 2012 through December 2020 as publisher and editor-in-chief of the online culture magazine REALKYOTO, and from February 2021 through March 2025 as editor-in-chief of REALKYOTO FORUM. Editor and author of the photo books One Hundred Years of Idiocy and its sequel One Hundred Years of Lunacy >911>311; author of Gendai āto to wa nani ka (What is contemporary art?) and Gendai āto o korosanai tame ni (So as to not kill contemporary art). Awarded the Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters by the French Government in 2019.