AIR and Me

Part 4: Everyday inspirations

By Shibata Hisashi

The eponymous simian was played by Hokkaido University student Muragishi Hiroaki, not an actor but a maker of music and visual art, in his first and ultimately only film role.

Monkeylove was shot in a wintry Hokkaido, and the mountain backdrop here is Mt. Yotei, known as Ezo Fuji (Ezo being the historical name for Hokkaido).

The previous instalment “AIR and Me, Part 3” discussed the history of AIR (Artist in Residence) programs in Japan at a macro level, offering an overview by recreating a map from the very early days of Japanese AIRs. This time, the discussion takes a microcosmic perspective to focus on the connection between day-to-day living and creativity, as experienced alongside a number of artists in residence.

Having been involved at ground level in a number of AIR programs over many years—primarily those organized by S-AIR, the non-profit I lead—it would be no exaggeration to say that one attraction of the AIR as a cultural enterprise designed to provide a supportive environment is its immersion in everyday life. How artists as temporary residents encounter an unfamiliar place, and come into contact with utterly new kinds of inspiration gleaned from cultural differences, is the very seed of creativity in the artist residency. For us as hosts, bearing witness to these moments also brings with it the great pleasure of rediscovering our local culture.

Royston Tan and rubbish sorting

2004 saw the start of an AIR project in mid-winter Hokkaido, courtesy of young Singaporean film director Royston Tan.1

Out of a straightforward interest in what he would film in the freezing Hokkaido winter, as someone from a place where it is always summer, Tan worked alongside a band of volunteers—S-AIR office staff, local artists, foreign artists undertaking concurrent residencies—to make a short film. Thus an entirely amateur enterprise. All we knew in advance was that the film was about “a monkey who had his heart stolen.” Was this serious, or a joke? No idea. The shoot took place in punishing conditions that included a snowstorm, without even knowing whether the product would be tragedy, or comedy.

“Sunday – No rubbish day. Monday – Burnable rubbish day. Tuesday – Recycling. Wednesday – No rubbish day. Thursday – Burnable rubbish day. Friday – Unburnable rubbish day. Saturday… What are you doing today?”

A verse from the narration near the start of the resulting short film, Monkeylove.

Rubbish sorting is surely one of the first everyday obligations explained to artists on their first residency in a place, any place. I don’t know how they go about it in Singapore, but the kind of meticulous dividing of waste required in tidy Japan, is probably one of the first aspects of Japanese living that people encounter, particularly overseas artists in residence experiencing Japanese life for the first time. The sorting of rubbish and progress of the week mark the passing of time during life in another country. And occasionally, perhaps, call to mind the lives of those from whom one is separated.

The completed film, just nine minutes in duration, evolved into a kind of cinematic poem, a complex blend of not just comedy and tragedy but other elements too, including documentary and fiction, video and 8mm cine camera.

Prompted by the later untimely accidental death of the young man in the lead role, as if to echo the tragedy of the story, three years after the residency the film whose maker described it as like nothing he had ever made before, was entered in the Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival, Europe’s largest event of its kind. Hailed there as akin to a haiku, Monkeylove won top prize in the festival’s Lab (experimental film) Competition for 2007.

Chang Yoong Chia and clam miso soup

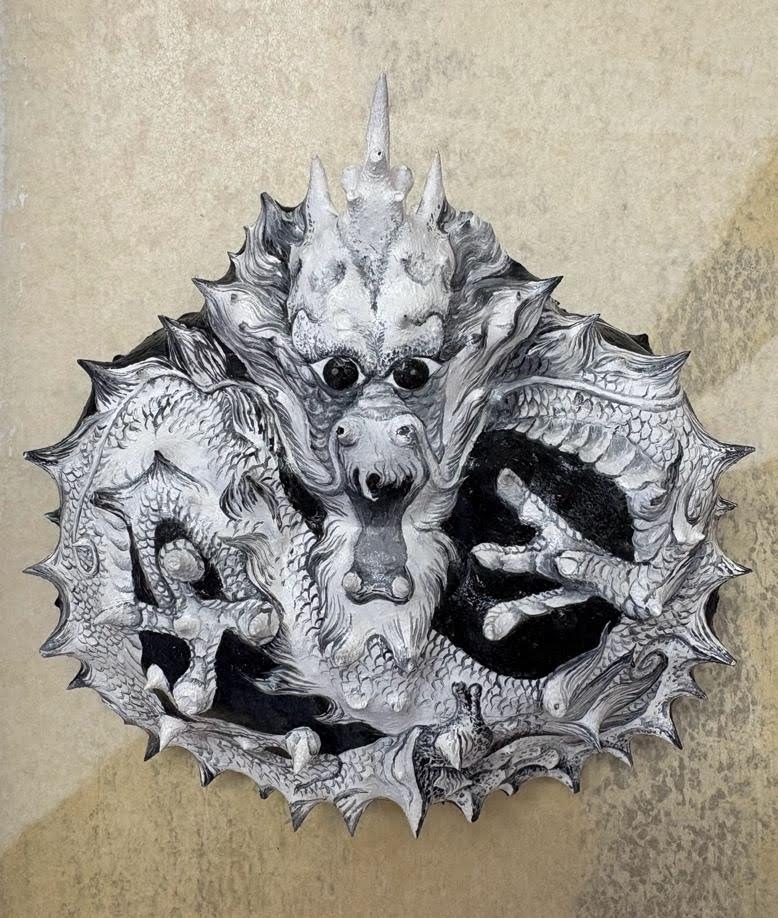

Fig. 2. Chang Yoong Chia, Dragon Drop Child, 2017

Dragon Drop Child in Fig. 2 is a dragon-like piece of object art that has adorned the S-AIR office since 2017. A memento of resident Chang Yoong Chia,2 from Malaysia (visited Hokkaido in 2008, 2017, 2019), can you tell what it is painted on? Actually the shell of a Hokkaido Hanasaki crab obtained from a bar in the Sapporo nightlife district of Susukino. Chang is an artist who crafts magical works from familiar, quotidian materials, and whose offerings include intricate two-dimensional works with silhouettes made from fallen leaves, and collages assembled entirely from piles of used postage stamps. Among his output are works created from materials new to most Japanese—the wings of white ants, dog skulls—but each routinely found in the location in question. The Japanese themselves have for centuries fashioned artworks from natural materials, but Chang’s proximity to nature feels more intense and mystical, although it is unclear whether this is a difference in how nature is viewed in Japan and Malaysia, or a quality of the individual artist.

The seafood (marine life?) of Hokkaido seems to have been a fascinating, not to mention accessible, material for Chang. Those that are together, Those that are apart in Fig. 3, is, believe it or not, made from miso soup with freshwater clams (shijimi) consumed by Chang in Hokkaido. Amazingly, paintings have been rendered on each of those diminutive bivalves. What seems to have been the artist’s first-ever encounter with this “dish of tiny shellfish” appears to have served as a special source of inspiration. Incidentally this photo was taken at a 2018 solo exhibition of work by Chang at Malaysia’s National Art Gallery.3 Who would have expected clam miso soup consumed in Sapporo to become a work of art exhibited at the national art museum of a faraway land?

Fig. 3. Chang Yoong Chia, Those that are together, Those that are apart, 2017

Aleksandar Dimitrijevic and Buddhist altar

My last example was unfortunately unable to be assimilated into a work, but is worthy of note here as an unforgettable case of artistic inspiration arising from an aspect of everyday living.

Artist Aleksandar Dimitrijevic,4 who came to Sapporo in 2002, had experience of the Yugoslav wars. Fighting to survive under wartime conditions had instilled in him a habit of picking rubbish from off the streets, and he seemed to bring home something new almost every day: a 1960s academic tome on the media, manga comics, adult videos (well, more cultural ones that were neither worn out nor damaged)…. For him, these items likely looked more treasure than trash. As hosts, we were not exactly enamored of such junk being brought into the apartment. On the other hand, we eagerly anticipated the transformation of these finds into art of some sort.

But… the artist’s magpie tendencies did not always work out for the best. One day Aleksandar contacted me saying he had picked up “this excellent really Japanese thing,” and asked us to come take a look. On arriving at his apartment, what should we find but a butsudan (Buddhist altar) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Japanese Buddhist altar (stock photo). The one he actually picked up was a little more austere in appearance.

There was no need to ask where it came from, because right in front of the apartment was a large temple. The altar seems to have been left there like an item of household waste, probably dumped by a parishioner after having it deconsecrated by the temple. Unsurprisingly we were somewhat taken aback, and fell into a quiet panic, suspecting that this was not really on. Sensing our discomfort, Aleksandar asked if he had done something wrong.

When he phrased it like that, we struggled to answer. He had probably committed no crime, because the altar was already discarded. However in Japan, picking up one of these would usually be considered taboo. Yet how to explain why?

“It’s a place where we meet dead people…”

“You mean a grave?”

“No, but…”

An almost comedic back-and-forth of mutual misunderstanding ensued.

No one there had ever even thought about what a butsudan actually was.

Later I did some research, and found that originally, in ancient India, people would mound up soil into an “altar” and enshrine “gods” there, as a sacred site. Such altars had roofs to protect them from the weather, and eventually, it seems, became temples. Today’s Japanese butsudan are a household version, a portable mini faith facility that apparently only emerged in the Edo period.

All Buddhist nations are not identical in this respect. While some have altars of similar significance, in other countries many of these altars have been lost, for example in China during the Cultural Revolution, which repudiated religion.5

This particular Buddhist altar may indeed have been a quintessentially Japanese cultural artifact, but even if it had been discarded by the original owner, from that owner’s point of view it was invested with thoughts and feelings for the departed. For a stranger to simply uplift it for use in a piece of art, well… as material for a work, it was a little problematic.

In the end, observing the obvious agitation among the Japanese around him, the startled Aleksandar returned the altar to where he found it, and thereafter, recoiled at any mention of the incident.

On the value of things in everyday life

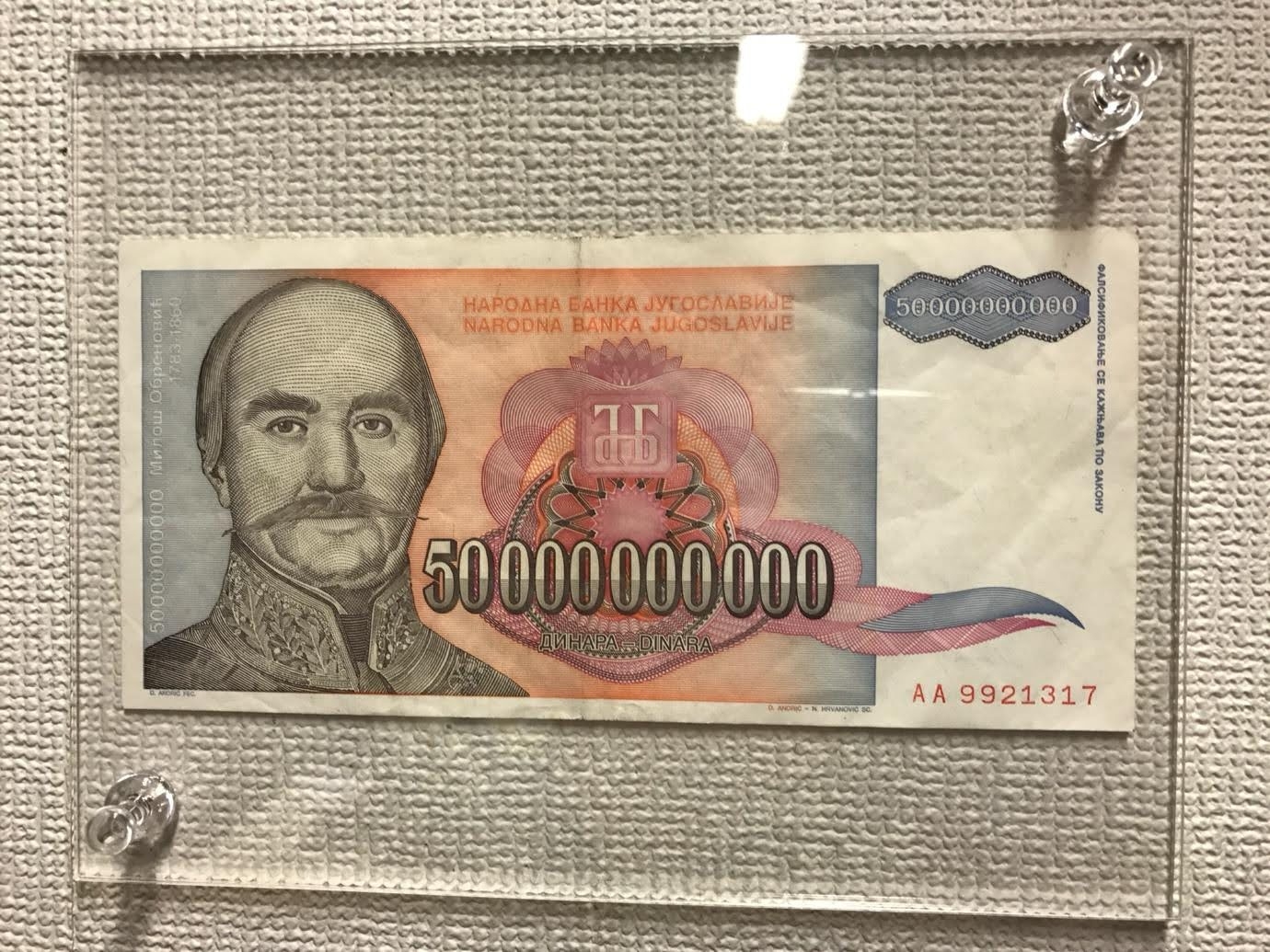

Fig. 5. 50,000,000,000 dinar note from the former Yugoslavia.

“What is rubbish? What is the value of things?”

It was not just the Buddhist altar; many of Aleksandar’s actions got me thinking.

Fig. 5 shows one of the 50,000,000,000 dinar notes from the former Yugoslavia that he handed out instead of business cards. This note had the most zeros of any at the time, with hyperinflation running at a million percent. Originally sufficient to buy dinner at a restaurant, by a month later these notes were worthless scrap paper blowing around the streets. In other words, money had turned into “rubbish.” It was directly after this that the conflict broke out.

As if determined to remind people of this period of history, Aleksandar gave out these notes to all and sundry instead of cards.

For artists whose lives are overtaken by war or disaster, the AIR can be a means of very survival. There are sure to be many artists from places like Ukraine and Gaza living elsewhere right now, making use of this AIR system.

Aleksandar is one who appeared to have survived in this way. He made political works denouncing the military that had caused the civil war in his country, but finding himself in the almost excessively peaceful surroundings of Sapporo, seemed lost as to what to express.

War destroys everyday life, and the “value” of things. Rubbish is what we discard as having no value as part of life. For those uninterested in art, works that don’t sell may seem like rubbish, but in a capitalist society, even money, that most trusted of objects, can occasionally become rubbish.

Artists take what people discard and give it new life as art. For some, that rubbish can thus also be riches. One could say that art has the ability to change the value of things.

Managing an AIR, I sense my day-to-day interactions with artists helping me rediscover the meaning of “everyday value.”

1. Royston Tan: Born 1976. Singaporean film director and actor. In addition to receiving numerous awards for his short films, has made several feature films including 3688 (2015), and 81 (2021). 2007’s 881 was the Singaporean entry in the 80th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film. Tan served as creative director for the Singapore National Day Parade in 2020 and 2023.

2. Chang Yoong Chia: Artist born 1975, residing in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Artist in residence in Sapporo in 2008 and 2017 at invitation of non-profit S-AIR, and in 2019 in the Hokkaido town of Shiroai as part of the Uymam Project. In 2018 staged “Second Life,” a solo exhibition of over 100 works at the National Art Gallery of Malaysia, to which the author was also invited as a talk guest.

3. “Chang Yoong Chia: Second Life,” National Art Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (Editor’s note).

4. Aleksandar Dimitrijevic: Born 1955 in Yugoslavia, based mainly in Belgrade. Makes works dealing with Yugoslav politics and social conditions, and in his 2002 residency in Sapporo, took a ridiculous message written in the street by the Serbian right wing and used it as inspiration for a work. In 2003 his home of Serbia became Serbia-Montenegro in federation with Montenegro, before the two countries split in 2006. Dimitrijevic’s current status is unknown.

5. Korea for example has a culture of Confucian-style ancestor worship (jesa), and people once had memorial tablets and altars at home enshrining ancestors, but with modernization, urbanization and the rapid uptake of Christianity from the 20th century onward, altars as permanent fixtures have been lost from many homes. Mongols too, influenced by Tibetan Buddhism, had a custom of enshrining Buddhist statues and altars in the home, but during the Soviet era household altars were destroyed under the Communist system. Buddhist altar traditions close to those of Japan today include the Vietnamese bàn thờ tổ tiên. (Editor’s note)

AIR and Me

Part 1: Sapporo as art studio—since “Ripple Across the Water ’95”

Part 2: Sapporo as art studio—since “Ripple Across the Water ’95”

Shibata Hisashi

Director, NPO S-AIR / AIR Network Japan

Over the 26 years since the Sapporo Artist in Residence (now S-AIR) executive committee era, Shibata has been involved in residencies and research by 106 artists and artist units from 37 countries, also in sending 24 Japanese artists/artist units to residencies in 14 countries. Since 2014 he has been a professor at the Hokkaido University of Education Iwamizawa Campus (Art Project Lab). A member of the executive committee for Res Artis General Meeting 2012 Tokyo, he is actively involved in the AIR Network Japan network of AIR organizations across the country, and in the launch of various art projects and art spaces. Co-author of What will change with the designated manager system? (Suiyosha), Basic research into the promotion of regional culture through art and cultural facilities utilizing abandoned schools (Kyodo Bunkasha), and Artist in Residence – The potential to connect towns, people, and art (Bigaku Shuppan). NPO S-AIR, which he heads, was awarded the Japan Foundation Prize for Global Citizenship in 2008.