Cultural Currency 37

A discovery at Art Taipei 2025

By Shimizu Minoru

Courtesy Xi Zhi Tang Gallery

Staged without a break since 1993, Art Taipei is Asia’s longest-running art fair.1 Upstaged by the entry of international brands such as Art Basel Hong Kong (2013–), Taipei Dangdai (2019–25), Frieze Seoul (2022–), in the last decade or so it seems to have faded in the local market, but looking from the outside at the stagnation, or rather recession, in the Asian art economy as embodied by the end of Taipei Dangdai and the slowdown in activity at the last Frieze Seoul, this year’s Art Taipei found a hallmark of its own different again from the populist line, a hallmark best described as the steadfastness of an old establishment.

Certainly, given the lack of top artists from the top Euro-America galleries, Art Taipei—as well as KIAF and the Tokyo Art Fair—basically features a line-up of artists popular at the local level. Shameless copycats merely scatter artistic commonplaceness full of déjà vu, not only hardly poised to lead the art world of the next generation, but a state of affairs a discerning collector would likely declare makes their eyes rot. Most are pragmatic art tradespeople who reckon on surviving in the so-called B-grade art market below the top market, as represented by Art Basel. As long as the “works” are accepted and bought by non-specialist collectors, whether despised as poor imitations or labelled simulacra, the anime characters (Ghibli, Eguchi Hisashi, Fujiko Fujio, etc.) and animal characters (tigers, rabbits, deer, etc.), soothing landscapes (sea, sky, clouds, forests, etc.), beautiful women and beautiful girls (the male gaze still rules!), detailed still lifes, trendy tapestries and prickly, twisting and turning or sparkling objects (the same taste as crows!) are single-mindedly repeated. This unbearable uniformity is the specialty of art fairs of this level, so is nothing unusual. Art Taipei, too, is basically supported by such galleries and artists. Audience attendance has thrived and sales were also apparently strong, and if popular items are sold in large volumes at reasonable prices (up to several million yen for the most expensive works), it is perhaps natural that it ended up thriving and producing strong sales. This model of catering to and relying on the B-grade market is no different to any local art fair, and it is not here that the special character of Art Taipei can be found.

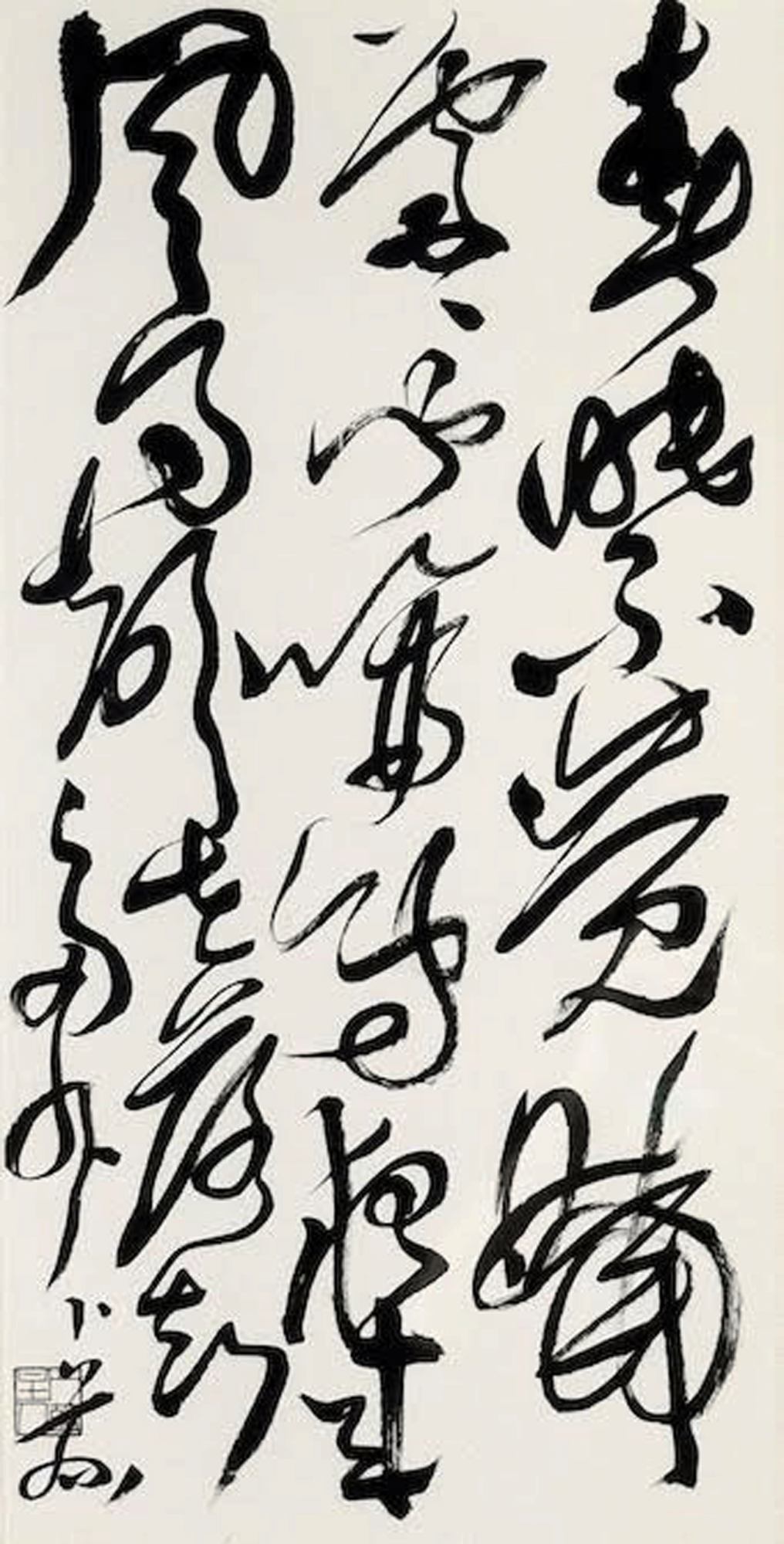

At this year’s Art Taipei, there was one genre of an especially high level even compared to the likes of Hong Kong and Seoul. This was avant-garde calligraphy. In recent years, the worlds of calligraphy and contemporary art have drawn closer to each other for the first time in 70 years, and I have commented in an earlier column on how the former is becoming absorbed into the latter.2 In fact, at Art Basel Hong Kong and Frieze Seoul, too, the incursion of calligraphy could be observed in several booths. However, leaving aside the work by masters such as Inoue Yuichi and Morita Shiryu presented by Japanese galleries, the Asian contemporary calligraphy displayed at the Hong Kong and Seoul fairs was without exception old-fashioned abstract calligraphy, lacking any sense of pursuing post-Inoue expression as shown by ASC (Art Shodo Contemporary). That pursuit could be seen at this year’s Art Taipei, and moreover it was entirely character-based calligraphy. Despite even ASC saying there was still room for abstract calligraphy, the contemporary calligraphy endorsed by Art Taipei was firmly based on characters.

Looking back, in the 18th century, at the height of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), modern calligraphy—modern calligraphy that did not emerge under the influence of Western modern art—already existed. According to Ishikawa Kyuyo, among the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou, in particular Jin Nong (1687–1764), Zheng Xie (1693–1766) and Yang Fa (1696–1752?), calligraphy based on rhythm (seppo)3 that had evolved throughout its long history in accordance with this rhythm (from two movements to three movements and ultimately multiple movements), pushed forward to unlimited movements (the dismantling of rhythm), freeing characters from rhythm and establishing the artform of calligraphy.

By achieving infinite freedom, calligraphy plunged into a stage of self-organization and self-movement, a modern age of autonomy.… For the first time, calligraphy was able to become independent as artistic expression. Furthermore, the self-evident notion of calligraphy emerging automatically or incidentally whenever characters are written was also dismantled at this time. Writing poetry or prose with a brush does not necessarily mean the creation of calligraphy; on the contrary, the expressive power of the brushstrokes came to rival, or even surpass the expressive power of the poetry or prose itself.4

The possibility that calligraphy might regress endlessly into a mere play of brushstrokes that lack dramatic technique (the necessity of dramatic development), as seen in so-called postwar avant-garde calligraphy, was in fact present in the unlimited movements and infinitely delicate brushstrokes of the Qing dynasty’s Jin Nong.5

The liberation of calligraphy and the attendant conflict between character calligraphy and abstract calligraphy already existed in the 18th century, and this leads directly to the avant-garde calligraphy of the likes of Nakabayashi Gochiku and Soejima Taneomi in Meiji period Japan. On the other hand, Hangul emerged on the Korean peninsula more than 500 years earlier, as a result of which it transitioned to a character sphere different from Chinese character culture, while China itself was cut off from the historical mainstream of Chinese characters after the war due to the introduction of simplified Chinese characters and the Cultural Revolution. It may be that only Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macao, and prewar Japan were able to preserve the historical continuity of calligraphy by continuing to use traditional Chinese characters.6 Despite this, postwar Japanese avant-garde calligraphy completely forgot the avant-garde calligraphy based on historical continuity that existed in the Meiji period, and instead became an ephemeral bloom that over-adapted to the superficial—the “retinal”—stimuli from modern art.

It was this avant-garde calligraphy based on historical continuity with classical calligraphy, something that had ceased to exist in Japan, that I discovered in 21st-century Taiwan. This was the work of Bu Zi (1959–2013), particularly the work from his later years. Exhibits of his work were underway at two locations: the Xi Zhi Tan Gallery booth at the Art Fair venue, and luckily also at Yi Yun Art in central Taipei. As seen in the accompanying photographs, Bu Zi’s calligraphy uses various styles and depicts not single words or characters but long poetry or prose with brushstrokes that rotate violently and flicker like flames. Video of the artist at work shows him writing vigorously at an unbelievable speed as if improvising.7 I do not know if Bu Zi’s calligraphy, which resembles the kyoso (wild cursive) style of Japanese calligraphy, referenced the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou. One of his works was a variation on a work by Huang Tinjian, so perhaps he was pursuing a path different from what Kyuyo Ishikawa called “unlimited movements.”

© Bu Zi, Four Calligraphic Panels of Chan Poems by Master Shiwu Qinggong, c. 2011

Courtesy Xi Zhi Tang Gallery

© Bu Zi, Fragrance in Motion, 2009

Courtesy Yi Yun Art

© Bu Zi, Autumn in the Mountains, 2008

Courtesy Yi Yun Art

© Bu Zi, Worn Cloak and Short Cane, 1999

Courtesy Yi Yun Art

© Bu Zi, Spring Dawn, 1997

Courtesy Yi Yun Art

1. In terms of age, NICAF (Nippon International Contemporary Art Fair) is a year older, but it ended after being held intermittently eight times from 1992 to 2003. KIAF (Korean International Art Fair) was first held in 2002, and the Tokyo Art Fair in 2005.

2. Shimizu Minoru, “Cultural Currency 28: ‘Soda Hirotaka Exhibition: Nihongo no shoji’ @ Kita Modern Art Museum: NI本GOWO巡RU政治 (The politics surrounding the Japanese language): The language art of Soda Hirotaka,” September 15, 2024. https://icakyoto.art/en/realkyoto/reviews/89022/

(Editor’s note)

3. The rhythm of placing the brush on the paper, moving it and lifting it. A two-movement rhythm is “ton, su” or “ton, gu” (the Wang Xizhi era); a three-movement rhythm is “ton, su, ton” (the era of Ouyang Xun and other Tang dynasty calligraphers); and a multiple-movement rhythm is a rhythm like “ton, tsu, tsu, tsuu, ton tsu, tsu, tsuu, ton, etc.” that freely combines these and other elements (the era of Huang Tingjian and other Song and Ming dynasty calligraphers).

4. Ishikawa Kyuyo, ed., Sho no uchu [The universe of calligraphy], vol. 21 (Nigensha, 2000), 11.

5. Ishikawa, 8.

6. Japanese gave rise to hiragana and katakana, but because the former originated in a very cursive style of writing Chinese characters, and the latter are fragments of Chinese characters, Japanese characters are essentially all variations of traditional Chinese characters. In postwar Japan, however, upon the introduction of peculiar Japanese simplified characters, Japanese was completely cut off from this historical continuity. Therefore, the legitimate successors to the Chinese classics are firstly Taiwanese calligraphers, then the tiny group of calligraphers in China and Japan who are carrying on the tradition of the Chinese classics.

7. “卜茲 (陳宗琛) – 書法作品創作 Chinese calligraphy by BuZi (CHEN Tsung-Chen),” Hanart TZ Gallery.(Editor’s note)

(All accessed December 9, 2025)

Shimizu Minoru

Art critic. Professor, Faculty of Global and Regional Studies, Doshisha University. Regularly contributes essays and critics for art/photography books, magazines and museum catalogues including those of Daido Moriyama, Gerhard Richter, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Wolfgang Tillmans and other Japanese and international artists.

Selected publications: “The Art of Equivalence” in Wolfgang Tillmans, truth study center (Taschen, 2005); “Shinjuku, Index” in Daido Moriyama (Editorial RM, 2007); “Fiction and Restoration of Eternity” in Hiroshi Sugimoto: Nature of Light (Izu Photo Museum/Nohara, 2009); “Daido Moriyama’s Farewell Photography” in Daido Moriyama (Tate Modern, 2012); “Guardian of the Void” in Palais no. 19 (Palais de Tokyo, Paris), 2014; “Post-Provoke et Post-Conpora: La photographie Japonaise depuis les années 1970” (Pompidou Metz, 2017).