AIR and Me

Part 5: Artists, post-AIR

By Shibata Hisashi

“How are you gathering information about residents after their AIR?”

This is a question I was asked just the other day by someone who appeared to be a local government worker.

It prompted me to write in this instalment of “AIR and Me” about something of interest to everyone involved in artist-in-residence (AIR) programs: what becomes of residents after they finish an AIR. This also relates to the essence of evaluating the effectiveness of AIR programs. With this in mind, I present the examples of two unforgettable artists.

Apichatpong’s case

It was in 2001, nine years before he won the top prize Palme d’Or at Cannes, one of the “Big Three” international film festivals, in 2010, that we hosted Apichatpong Weerasethakul, a “two-sword fencer” who both directs movies and is a regular participant at international art exhibitions, making him somewhat unusual in the art world. To date, he has only taken part in AIR programs twice, once in Sapporo and once in Paris, with his experience at Sapporo’s S-AIR, which I am involved in running, being his first at the age of just 26.

Apichatpong took part on the recommendation of Hirose Satoshi, a Japanese artist who has worked in Thailand, although at the time he applied, many of his video works featured amateur performers, and to be honest, back then I could not really appreciate their merits. But we had few applications at that stage, and one of our directors was an artist who attended the same film school in Chicago where Apichatpong studied, so after reviewing the other material he sent, we thought it “might be interesting” and decided to accept him.

However, soon after he turned up in Sapporo, to our surprise an invitation addressed to Apichatpong arrived from the Istanbul Biennial. It was a personal offer from Hasegawa Yuko, the first Japanese to serve as the biennial’s artistic director. Thinking this was a one in a thousand chance for an artist, although we had only just arranged a Japanese visa for him, we decided to cooperate by delaying the timing of our AIR.

We later learned that this offer from Hasegawa was the first instance of Apichatpong, who is basically a filmmaker, being pulled onto the international stage of the art world.

He later spent around two months in Sapporo, a little shorter than planned, where his activities included creating an experimental video using collage, a work in which he had a Japanese filmmaker shoot a Thai melodrama set in Japan, and other equally original, memorable works.

Fig. 1. Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Are you happy? balloon project (2001). Staged during the artist’s stay in Sapporo.

The photograph (fig. 1) depicts Are you happy? a performance in which 100 balloons with return postcards bearing the message “Are you happy? Why is that?” attached to them were released from a local riverside. What surprised me is that Apichatpong said he would not film this work. “I’m no good at creating stories,” he commented, “so I collect them instead.” Despite being a filmmaker, he also makes works that don’t involve filming. I realized that this flexibility is a quality of this artist that resonates in the art world, too.

Incidentally, just one of the postcards came back.It seems a couple visiting Furano on their honeymoon found one of the red balloons in a field. As for the question “Are you happy?” of course the “Yes” was circled.

Apichatpong after his AIR

In 2015, 14 years after his stay in Sapporo, we invited Apichatpong back to give a talk about his subsequent activities. We learned that he had shot a movie in his native Thailand but that it had not been screened, because he was protesting the strict censorship of works under the influence of the military. In other words, despite having won one of the most prestigious film awards in the world, it seemed he had not been properly recognized (at least by the state) in his home country.

Conversely, however, he was becoming increasingly active in other countries, and in that same year in Japan, coinciding with the release of his film Cemetery of Splendour, he took part in many activities, including participating in multiple international art festivals, teaching classes at universities and giving talks. One could a say it was truly “Apichatpong’s year.”

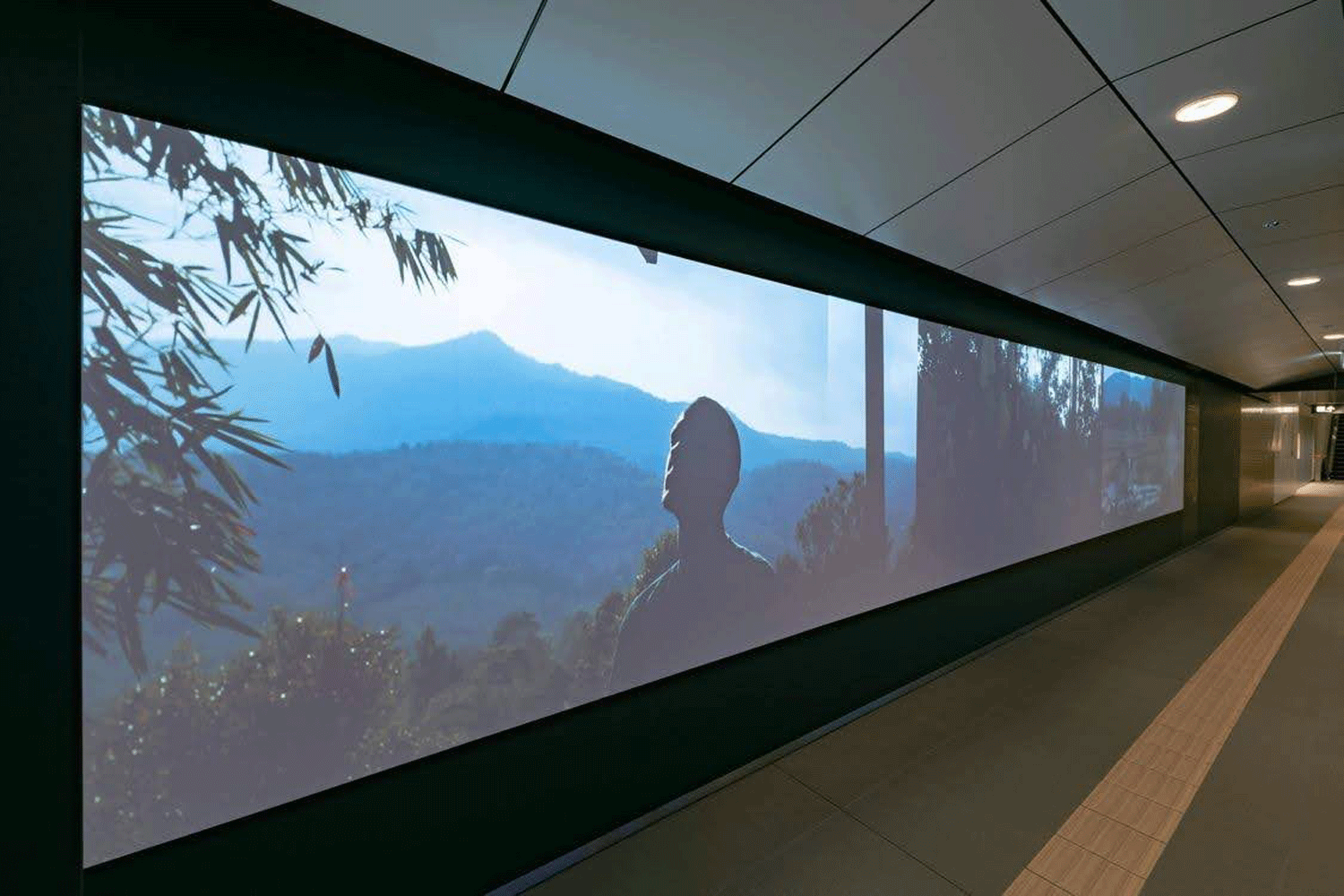

Five years later, in around 2020, on the occasion of the establishment of Sapporo’s new arts center, SCARTS, a new staffer at the Sapporo Cultural Arts Foundation inquired about the creation of a work to be installed in an underground passageway connected to SCARTS. This was to be a piece of public art screened on a rotation basis with works by other artists already in SCARTS’s collection in a special screening environment using three projectors to display video works measuring in excess of 7 meters (fig. 2).

In what might be called the silver lining of a dark cloud, because it was right at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and Apichatpong was able to find time in his busy schedule to create something, he said that although he could not visit Sapporo, if something made in Thailand was acceptable he could send it, and so it was that the work came about.

At the time of his invitation to the AIR in 2001, Apichatpong was unknown in Japan and unrecognized by any local governments, but 20 years later he had gained recognition and his work had been purchased. The work, The Longing Field, would be Apichatpong’s only permanently installed public artwork in the world (fig. 2). What greater honor and blessing could an AIR organizer hope for?

However, four years later, in 2025, the Sapporo Cultural Arts Foundation announced, “A projector is broken and we have no appropriation for repairs, so we have decided to stop screening the works. We hope you understand.” Apichatpong’s work was removed within the minimum contract period of five years. This treatment was a little shoddy as the cultural policy of a major city with a population of nearly 2 million people. Given that The Longing Field is a site-specific installation using a complex three-projector, six-screen display, finding another venue will be a challenge, and there is a risk that it might slip into obscurity.

Fig. 2. Apichatpong Weerasethakul, The Longing Field (2020–24), installation in the underground passageway connected to the Sapporo Cultural Arts Community Art Center (SCARTS), dismantled (unfortunately) in 2025.

Prigov’s case

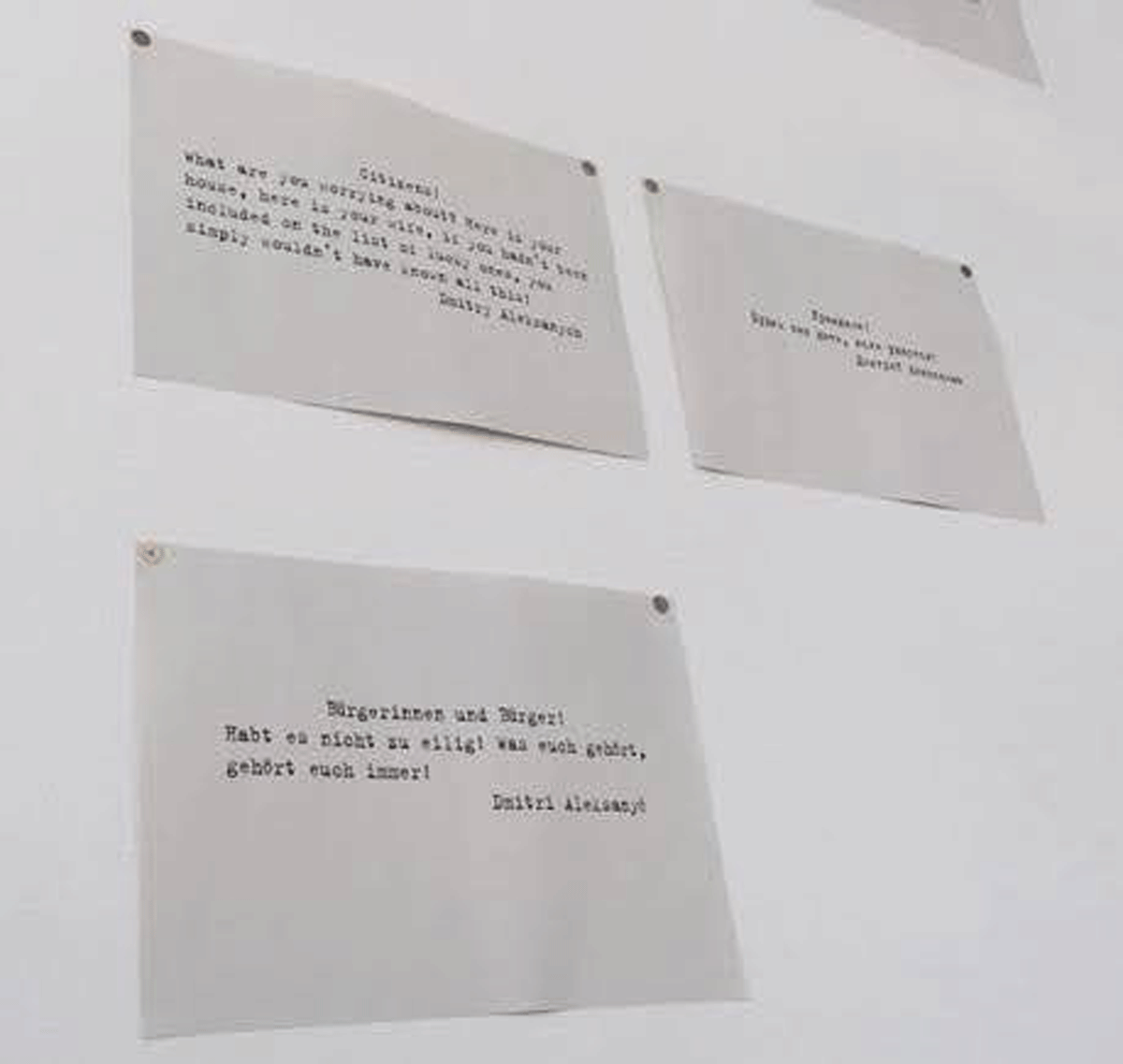

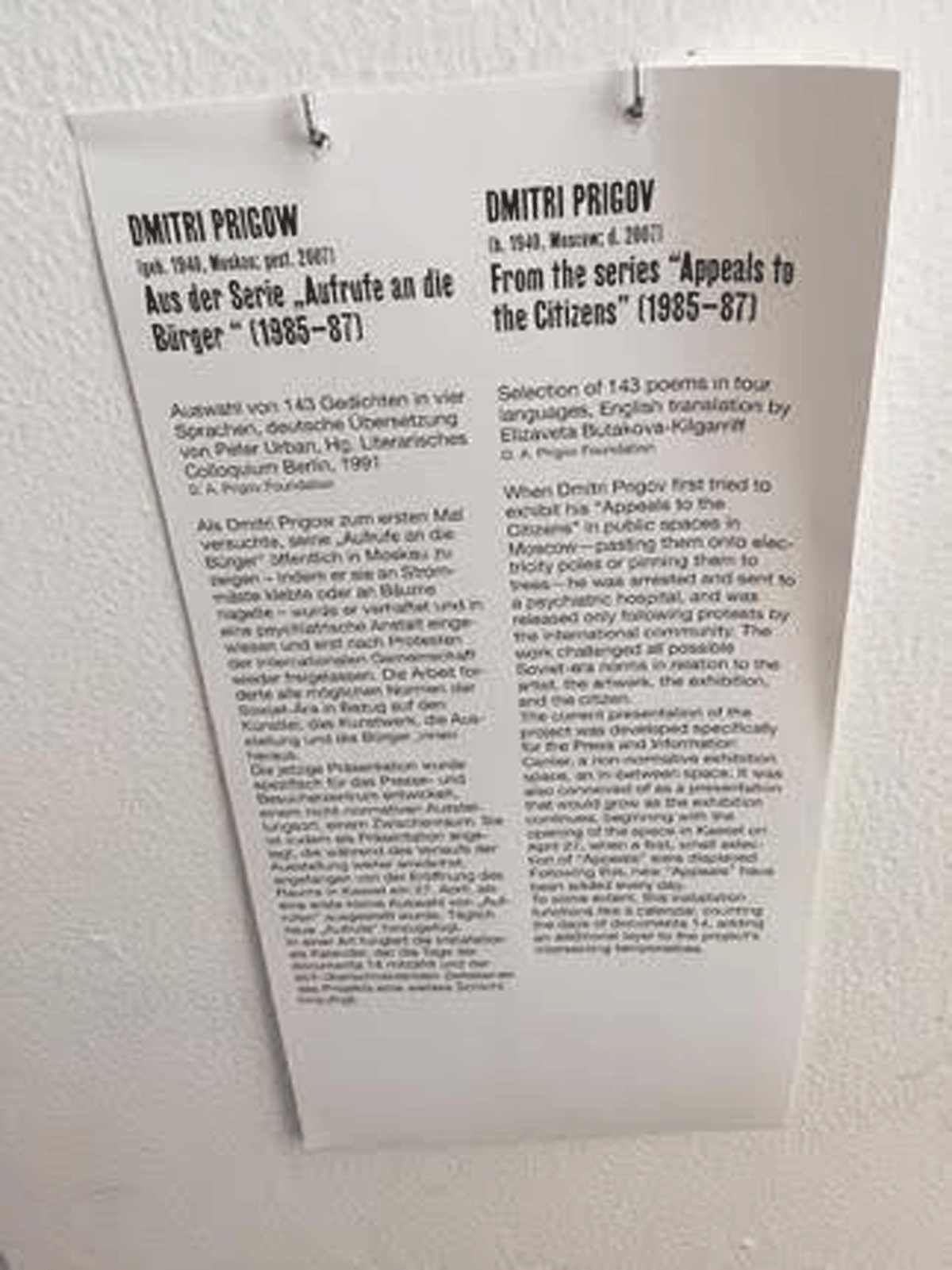

When Dmitri Prigov first tried to exhibit his “Appeals to the Citizens” in public spaces in Moscow—pasting them on to electricity poles or pinning them to trees—he was arrested and sent to a psychiatric hospital, and was released only following protests by the international community. The work challenged all possible Soviet era norms in relation to the artist, the artwork, the exhibition, and the citizen (from commentary in fig. 3).

At the international art exhibition documenta 14 held in 2017 in the German city of Kassel, a work comprising a collection of notes from different periods was displayed in the Press and Information Center. The artist was Dmitri Prigov. Having passed away in 2007, he had been selected for this “dream stage”—widely regarded as the Olympics of contemporary art—a full decade after his death.

Fig. 3. Dmitri Prigov, from the series “Appeals to the Citizens” (1985–87), installation view at documenta 14 (2017). Photo Tachibana Kyoko.

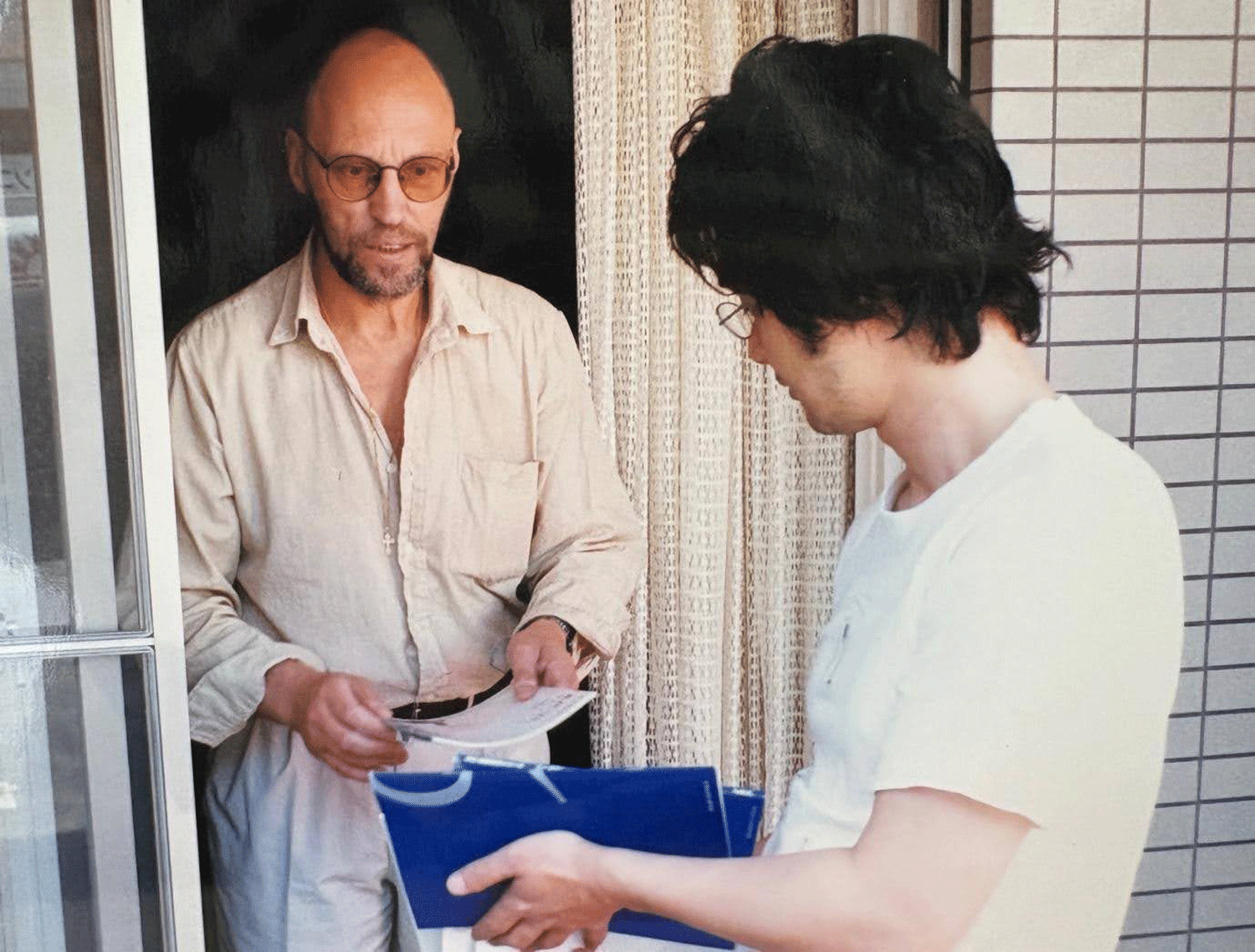

In fact 17 years earlier, in 2000–2001, Prigov spent three months living and making art in a room right next-door to the apartment in Sapporo where I lived as part of a program run by the non-profit S-AIR, of which I was the director (fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Dmitri Prigov and me at his apartment in Sapporo (2001).

Dmitri Prigov was a multi-talented Russian artist who worked as a poet, painter, actor, and TV commentator among other things, but his lifetime was marked by adversity. As a result of trying to paste the poems written on pieces of paper that make up Appeals to the Citizens (1985-87) around Moscow, he was arrested and confined to a psychiatric hospital.1 It was only after Mikhail Gorbachev’s perestroika reforms took effect that he was able to pursue his practice freely, and his stay in Japan coincided with this period in his life.

During his time in Sapporo, Prigov produced three large drawings measuring over 150 cm and 55 intricate A3 and A4 size drawings, held an exhibition based on these works (fig. 5), staged a voice performance, plus gave lectures at several Japanese universities, mainly those with courses in Russian literature, and even appeared on NHK’s Russian language course.

Prigov was already 60 years old at the time of his visit, but I think for him this period, freed from repression following the perestroika reforms, was like an adolescence. Because S-AIR is a very small, independent organization, our support was limited. Nevertheless, Prigov was deeply appreciative, and upon his return home, he left behind nine unique original drawings created for the individuals who had supported him during his stay (a number of which are still kept at S-AIR today).

Prigov after his AIR

After returning to Russia, Prigov appeared often on TV, and became widely recognized by the Russians public. He also published a novel set in Japan, Only My Japan (2001),2 in Russian so I cannot read it, but apparently dreamlike and surreal. Thus he became a far more prominent figure than the artist we knew at S-AIR.

Unfortunately, in 2007, six years after returning to Russia, Prigov died at the age of just 66, however soon after his death the Hermitage Museum hosted a major retrospective and acquired many of the works he created in Sapporo. Among them is a drawing on the theme of the kanji for “monster”3 that I taught him.4

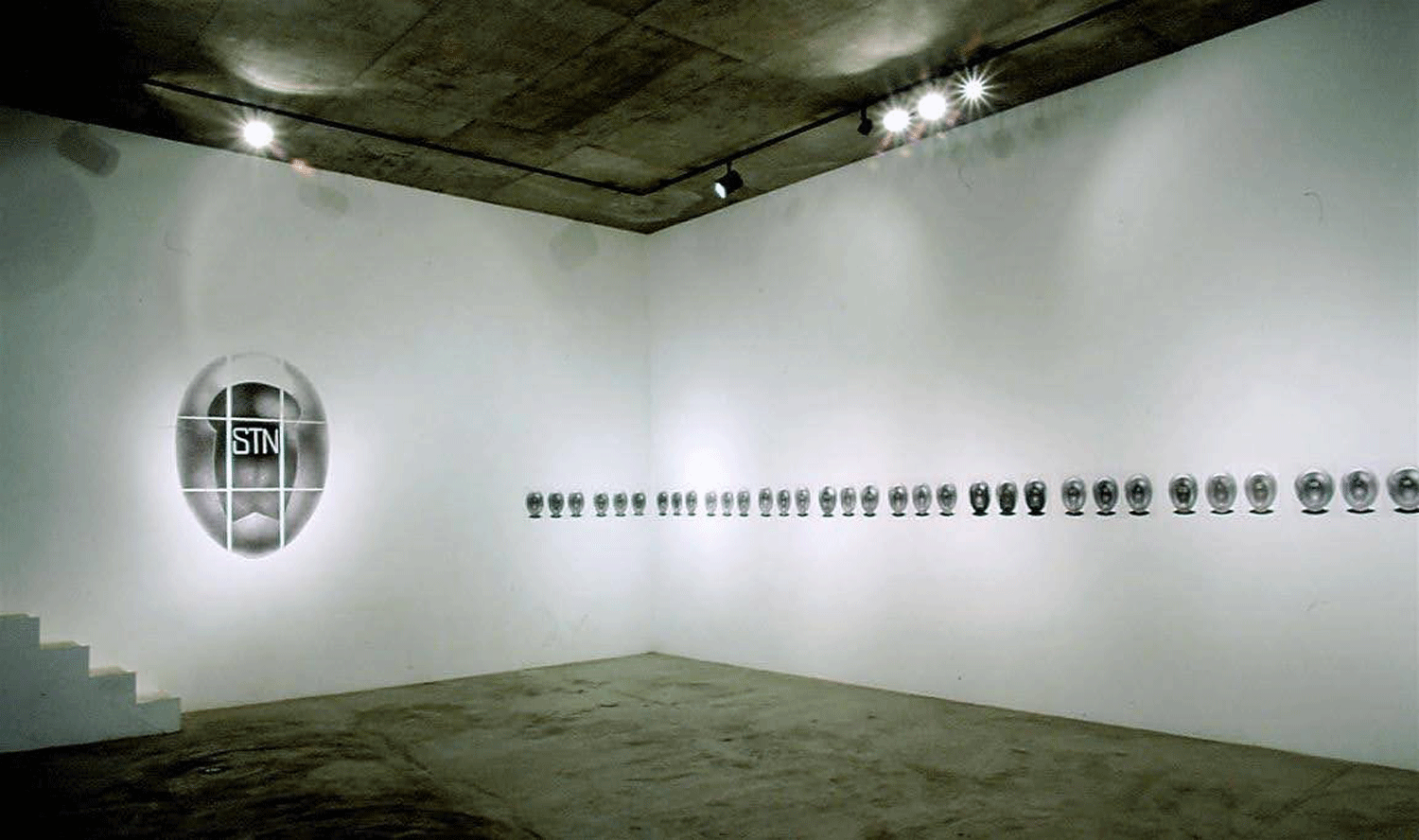

Fig. 5. Dmitri Prigov, egg world silence, 2001. Installation view at CAI Contemporary Art Institute (Sapporo). The work consists of eggs drawn in ballpoint pen, with various letterforms written inside.

“Residents after they finish” and AIR program evaluation

The two residents I have focused on, Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Dmitri Prigov, both achieved considerable success as artists after their stays in Sapporo. However, I think it is clear that such assessments vary from period to period and place to place and change by the moment.

What these two artists have in common is that they lacked adequate creative environments in their home countries. For such artists, artist-in-residence programs that provide creative environments serve an extremely important function.

In addition, in the example of Prigov, one can perceive the essential special characteristic of “art and culture.” This is something that can rarely be seen in other industries. Here I am referring to how after an artist’s death, their career can advance or develop. This stems from the fact that artists produce separate lives in the form of “artworks” that could also be called their alter egos.

In cases where outstanding artworks are created, these sometimes live on semipermanently beyond the lives of the artists themselves. In some cases, these later become regional cultural resources or tourist resources. This should be clear if one looks at ancient cities such as Rome or Paris, Nara or Kyoto.

It is a good thing that in recent years, people in Japan are getting excited about regional arts festivals and the like, but we need to be cautious of the tendency to connect too hastily to this local industrialization. I also think it could lead to the careless consumption of the value of art and culture, which rightfully should be nurtured slowly over many years.

“How are you gathering information about residents after their AIR?”

Returning to the original question, in my case the answer is simple. “I want to keep track of their activities naturally by going to the places where they live and inviting them to come back after a while, and to accompany them forever while interacting with them over the long term as neighbors.”

Using various data and indices is fine, but I want to ensure we never lose sight of the essence of this work, which is “people-to-people exchange.” I think it is vital to see the process through until it matures into culture.

1. Prigov discussed the incident in an interview with Gennady Katsov, published in the August 5–6, 2000* issue of Novoe Russkoe Slovo / New Russian Word, New York. (*while Prigov was in Sapporo). Japanese translation: Kudo Nao / Нао Кудо, February 26, 2018. 2. только моя Япония, (2001).

3. From the “Long Monster” series (2000–), S-AIR June 2000-February 2001, (S-AIR, 2001).

4. From a research report by Momiyama Masao and Kono Wakana (2015).

*References and information provided by Kono Wakana.

(All accessed December 27, 2025)

AIR and Me

Part 1: Sapporo as art studio—since “Ripple Across the Water ’95”

Part 2: Sapporo as art studio—since “Ripple Across the Water ’95”

Shibata Hisashi

Director, NPO S-AIR / AIR Network Japan

Over the 26 years since the Sapporo Artist in Residence (now S-AIR) executive committee era, Shibata has been involved in residencies and research by 106 artists and artist units from 37 countries, also in sending 24 Japanese artists/artist units to residencies in 14 countries. Since 2014 he has been a professor at the Hokkaido University of Education Iwamizawa Campus (Art Project Lab). A member of the executive committee for Res Artis General Meeting 2012 Tokyo, he is actively involved in the AIR Network Japan network of AIR organizations across the country, and in the launch of various art projects and art spaces. Co-author of What will change with the designated manager system? (Suiyosha), Basic research into the promotion of regional culture through art and cultural facilities utilizing abandoned schools (Kyodo Bunkasha), and Artist in Residence – The potential to connect towns, people, and art (Bigaku Shuppan). NPO S-AIR, which he heads, was awarded the Japan Foundation Prize for Global Citizenship in 2008.