AIR and Me

Part 6: AIR DNA

By Shibata Hisashi

Welcome to the final instalment in this series. Below is an exchange I had 4 or 5 years ago with a staffer at the Sapporo non-profit S-AIR, which I am involved in running.

“Why are you running S-AIR? Is there a goal in terms of how you want it to be?”

“Hmm… Maybe I just want its DNA to survive…”

I was recalling this conversation I had 4 or 5 years ago with a staffer at NPO S-AIR. Seeing the startled look on her face, in response to my statement, I quickly returned to my senses.

What I wanted to get across was that S-AIR was a minor nonprofit AIR organization that had miraculously survived despite constantly facing the prospect of going under, and that at the very least I wanted some kind of DNA to survive.

However, after seeing the surprised face of the staffer, I have continued to search anew inside myself for an answer to the question, “What for me is the ‘AIR DNA’ that I want to leave behind?”

Before rushing to a conclusion, I would like to touch on what I was thinking and how I viewed the S-AIR I am involved in running and Japanese AIR programs in general last spring when I began this series.

The Agency for Cultural Affairs AIR support crisis

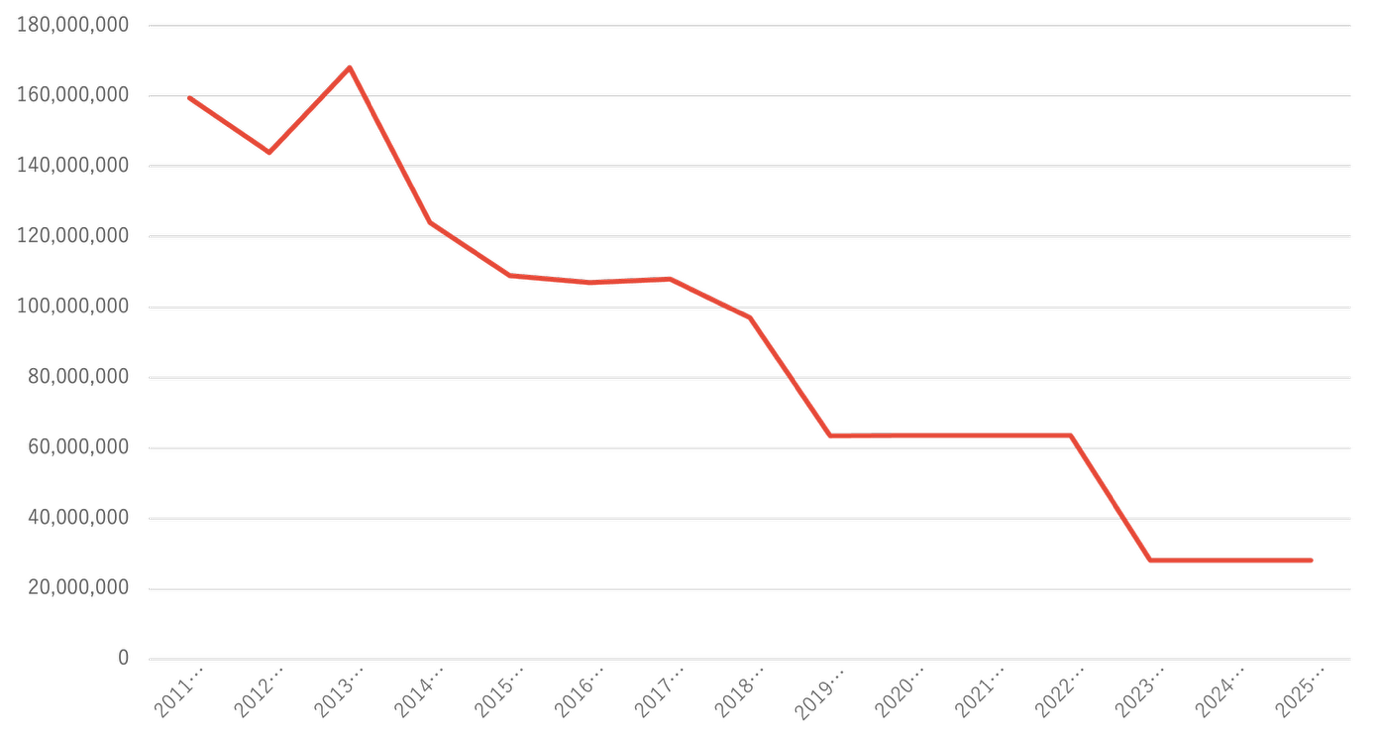

In 2023, the Agency for Cultural Affairs budget for Artist-in-Residence (AIR) programs, which had been continuing for 12 years, was suddenly and without prior notification cut by 60 percent, a move that impacted many AIR organizations. The Agency’s assistance for AIR has remained at the low level of 28 million yen, around 1/6 the level at its peak, for three years in a row, and in terms of the country’s support for cultural activities it is in an extremely precarious position (see fig. 2).

Fig. 2: The Agency for Cultural Affairs’ budget for Artist in Residence programs (the second round of AIR assistance/2011–25)

Graph updated by the author based on data presented by Kanno Sachiko at the 1st Air Network Meeting, Tohoku.

At the time of this dramatic reduction in AIR assistance by the Agency for Cultural Affairs in 2023, the Sapporo non-profit S-AIR also missed out on selection, threatening the organization’s existence.

For the previous 24 years, S-AIR had invited 105 artists from 37 countries and offered them full support (travel costs, accommodation/living costs, material costs, human support). I have not heard of another completely nongovernmental organization in Japan that has continued providing full support for such a length of time, and for an organization in a provincial city in particular it was probably miraculous.

By chance we had no unfinished projects, no debt and no employees, and to cap it off we were approaching our 25th anniversary, so the timing seemed appropriate to call it a day and end our activities. But the one thing that concerned me was the question, “Is now really the time?” After all, wasn’t this critical situation a problem not only for one region represented by Sapporo’s S-AIR, but a nationwide problem?

Partly because at the time S-AIR was one of Japan’s oldest AIR organizations, our decision would probably have had no small impact on other organizations, so we discussed the matter with another AIR organization we belonged to, AIR Network Japan, and together we contacted AIR insiders and nongovernmental arts and cultural groups around the country and waited for an opportunity to meet.

The beginning of AIR Network Meeting

In January 2024, the 1st AIR Network Meeting Tohoku “What happens now? Artists in Residence Japan” (see fig. 3-1) was held in Shiogama and Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture. Although held on a fee-charging basis, it attracted 66 participants from 25 organizations in 21 Japanese prefectures and the UK who took part either in person or online.

On Day 1, the Ogasawara Toshiaki Memorial Foundation, which funded and supported the conference, announced it would provide emergency assistance for the Noto Peninsula and proposed an AIR project interpretation for this support.

Subsequently, the 2nd AIR Network Meeting Hokuriku “Disaster and Tourism” was held in Eiheiji, Fukui Prefecture in November 2024 (see fig. 3-2), and the 3rd AIR Network Meeting Expo 2025 Osaka, Kansai “Organizations and Networks” was held in the Netherlands Pavilion at the Expo site in May 2025 (see figs. 3-3). In March 2026, the 4th AIR Network Meeting Kyushu “Art and Migration” (see fig. 3-4) is scheduled to be held. The conferences are held across Japan with no specific regional base while touching on the arts and cultural situation in locations throughout the country.

Fig. 3-1: Banner for the 1st AIR Network Meeting

Fig. 3-2: Banner for the 2nd AIR Network Meeting

Fig. 3-3: Banner for the 3rd AIR Network Meeting

Fig. 3-4: Banner for the 4th AIR Network Meeting

The current state of the changing AIR scene in Japan

In the course of holding these AIR Network Meeting events, the changing nature of AIR in Japan has become clear. As touched on in “AIR and Me Part 3: The first map,” while on the one hand the Agency for Cultural Affairs assistance for AIR programs is dramatically decreasing, the number of AIR programs and residents is steadily increasing, a situation explained by the following three factors: I. The diversification of operating organizations, II. Public support from sources other than the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and III. Self-funding in the inbound era.

I. The diversification of operating organizations

As I wrote in “AIR and Me Part 3,” when the Agency for Cultural Affairs began inviting applications for assistance in the late 1990s, most AIR organizations took the form of executive committees, but they have since become more diverse, and accordingly their operating funding has also diversified. Currently, less than a tenth of AIR organizations receive support from the Agency for Cultural Affairs.

II. Public support from sources other than the Agency for Cultural Affairs

While Agency for Cultural Affairs assistance has dramatically decreased, public support itself is not decreasing.

The Hamacul Art Project and Hama Connected, both operating in Fukushima Prefecture since 2023, are Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry-led AIR programs designed to encourage people to stay in or move to Fukushima Prefecture, and operate with budgets several times larger than the current Agency for Cultural Affairs AIR support.

As well, as a recent trend, there are several examples of artists creating works during residencies using the Local Revitalization Cooperator scheme. The responsibility of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, this scheme is a large undertaking that involved the movement of 7910 people in fiscal 2024 alone, and in some cases AIR-like interpretations have begun to arise.

One could also view this as evidence that public AIR assistance by the state is actually increasing beyond government ministries and agencies.

III. Self-funding in the inbound era

The greatest change as I sense it is the change in the nature of AIR programs. Due to some extent to the recent increase in inbound visitors, the number of self-funded AIRs in which artists pay their own way like staying in a hotel is increasing.

Until recently, the majority of AIR programs employed the full support model in which the Japan side pays all expenses, including travel costs, accommodation/living costs, material costs and catalogue costs, and this hospitality is also the basis of the Agency for Cultural Affairs’ system and has been adopted by organizations like S-AIR that have existed since long ago.

However, compared to the dawn of domestic AIR programs in the 1990s, regional arts festivals are experiencing a boom and foreigners and artists themselves are no longer uncommon even in the regions. In fact, we have entered an era in which, as is the case in Kyoto, the negative impact of over-tourism can be seen.

“From AIR programs that pay money to attract artists, to AIR programs that accept money to host artists.”

In line with the government’s policy of promoting “profitable culture,” it seems that a change in the nature of AIR programs is also becoming conspicuous.

There are probably those of the view that if these self-funding model AIR programs are successful, there will no longer be a need for public support of culture. Certainly, there are some new facilities that are operated without receiving any cultural assistance at all.

However, the users of such facilities tend to be economically well off. As well, unless there are benefits for users in that the locations, buildings, organizations and service are in their own way attractive, or that the fees are cheap due to public assistance, it is difficult for them to succeed.

But an important advantage of self-funding is that—whereas under the full support model, due to the high proportion of public funding, selection is carried out by inviting applications meaning it tends to be highly competitive—it is rather easy to realize. I have used this model on a number of occasions, and because it is easy to put together a program, it is suited to residents who are able to visit with assistance from their own countries. It is also a model that has spread widely overseas and is familiar to overseas residents, and with the weak yen it will probably become more common in the future.

The objectives and DNA of AIR

Because the AIR system is inherently a scholarship system aimed at artists, it is a cultural enterprise that is not profitable on its own. However, as long as the structures are in place, it is a cultural activity that can be launched quickly even in regional cities. The use of a number of properties is required, such as housing, studios and exhibition spaces, but in the regions if vacant houses are used, for example, it can be begun quickly and can also contribute to solving local problems. As well, it can also become an activity that supports other events such as arts festivals. With luck, it can also give rise to artworks that rediscover local resources while also becoming part of a region’s historical and cultural heritage.

As someone who has always loved regional/local revitalization, I find that the objectives of AIR programs naturally align well with the concept of “local.” All the more so in the case of Japan, which has in recent years been visited by a succession of natural disasters. Looking at the current state of Japanese AIR programs receiving public assistance, it appears that the Agency for Cultural Affairs, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications all have as the goal of their support local development.

However, should the objectives of AIR programs be this alone? Because if the objective is local development, the means need not necessarily be art and culture. One can think of various objectives for AIR programs other than local development. Examples include:

・International exchange・The promotion of art and culture

・Education (including the nurturing of artists)

・Welfare (people with disabilities, older people, etc.)

・The promotion of industry (including tourism)

・Cultural diplomacy

・Freedom of expression and the preservation of life and the environment

Of the above objectives, the most important in my opinion is “Freedom of expression and the preservation of life and the environment.”

If were to redefine AIR, I would say it is a cultural enterprise that provides an ideal environment for guaranteeing the freedom of expression and thought, and the livelihoods of artists. This I believe is the most vital element of the AIR DNA.“Art and culture” and “region” are not necessarily compatible.

Why do artists move from place to place? Many residents who move from place to place are artists who have to move because that have fled a “region” where they cannot secure adequate freedom of expression. Some have even abandoned the largest “region,” i.e., their own country. And by providing such artists with an environment in which they can express themselves free from fear, important works often emerge. Herein lies a vital characteristic of the art and culture—freedom of expression—and a core facet of AIR programs.

We must not forget that AIR programs are run not just to appeal to others who are visiting our own region, but also for the benefit of others receiving them.

Today, as the world situation becomes increasingly unstable, I think the significance of this “DNA” is becoming ever more important.

Finally, I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have provided information and otherwise been involved in the preparation of these articles. Thank you.

AIR and Me

Part 1: Sapporo as art studio—since “Ripple Across the Water ’95”

Part 2: Sapporo as art studio—since “Ripple Across the Water ’95”

Shibata Hisashi

Director, NPO S-AIR / AIR Network Japan

Over the 26 years since the Sapporo Artist in Residence (now S-AIR) executive committee era, Shibata has been involved in residencies and research by 106 artists and artist units from 37 countries, also in sending 24 Japanese artists/artist units to residencies in 14 countries. Since 2014 he has been a professor at the Hokkaido University of Education Iwamizawa Campus (Art Project Lab). A member of the executive committee for Res Artis General Meeting 2012 Tokyo, he is actively involved in the AIR Network Japan network of AIR organizations across the country, and in the launch of various art projects and art spaces. Co-author of What will change with the designated manager system? (Suiyosha), Basic research into the promotion of regional culture through art and cultural facilities utilizing abandoned schools (Kyodo Bunkasha), and Artist in Residence – The potential to connect towns, people, and art (Bigaku Shuppan). NPO S-AIR, which he heads, was awarded the Japan Foundation Prize for Global Citizenship in 2008.