GAT 028 Greg Dvorak

ELEPHANTS IN OUR LIVING ROOM: PACIFIC ISLANDER RESISTANCE, RESILIENCE, AND SOLIDARY DESPITE JAPANESE AND AMERICAN EMPIRES

Dr. Greg Dvorak, an independent curator of Pacific and Asian cultural studies who teaches at Waseda University, talks, “The entanglement of the “ghost” of Japanese empire and the ongoing hegemony of American empire serves as a barrier to connection between multiple colonized and militarized communities around the Asia Pacific region…” The Pacific Ocean, the world’s largest ocean that right next to Japan. How much do we know about what happened there in the not-too-distant past? The following is an excerpt from a talk given on July 3, 2021.

* The images used in this article have been permitted for educational purposes. All presentation images are copyright Greg Dvorak.

Edited by Ishii Jun’ichiro (ICA Kyoto)

Marshall Islands

So why me? Why am I doing this?

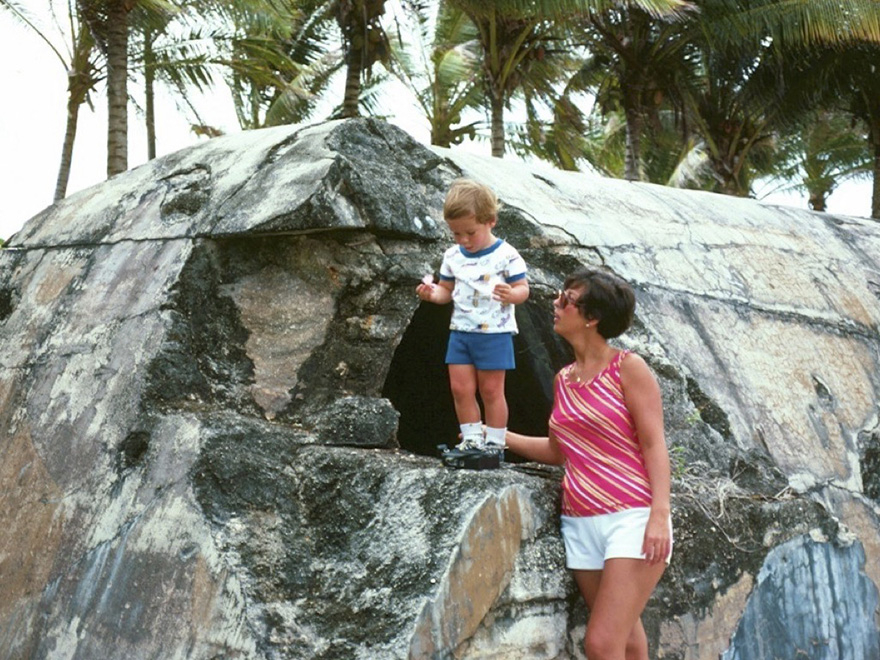

This is me at the age of 3 years old, walking on the beach of Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands.

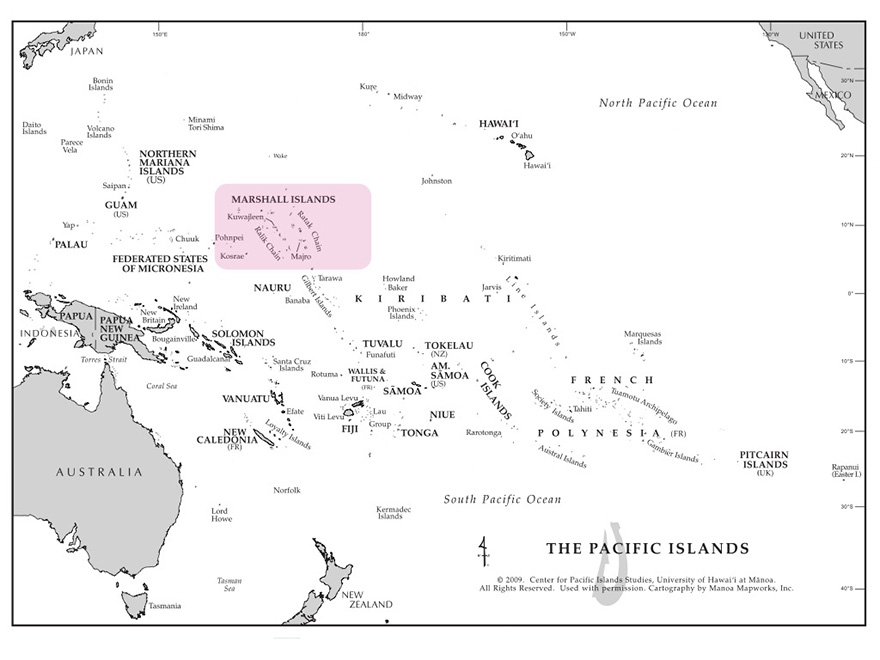

In the Pacific Islands region, there are over 25,000 islands, and within this we can see the Marshall Islands, north of the equator.

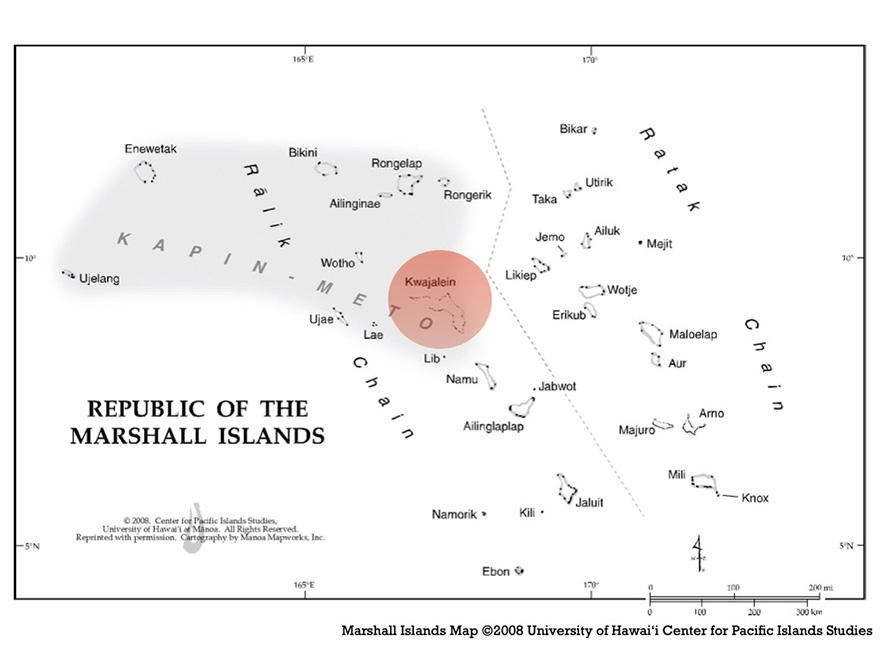

An independent country since 1986, it comprises 2 million square kilometers of ocean. In the middle of the Marshall Islands, you can see Kwajalein, the largest inhabited atoll on earth.

And this is the main island of that atoll. There are over 100 islands within the atoll. If you look at this, you can see a very big airstrip, two swimming pools—a very comfortable looking island.

This is me, again in 1976 as a child, and I’m wearing a T-shirt, which says “Almost Heaven, Kwajalein”.

But it was not really heaven. This was actually a military base. It’s a very important military base for the United States army and it was also a very important navy base for Japan. In fact, this island, this atoll, was part of the Japanese Nanyō Guntō (South Sea colonies) in the Pacific.

This photo is of me climbing on a bunker from World War II. This is a Japanese bunker. It was constructed by Korean laborers, forced laborers from Korea who were taken there against their will by Japanese military and naval forces to build bases for the Japanese military.

You see things like this all over Micronesia. You see these bunkers in Palau, in Saipan, in the Marshall Islands, in the Federated States of Micronesia— in many, many places where the battles of the Pacific war took place, even today.

So here you see a building that is another kind of bunker. It’s a concrete bunker from the Cold War, built by Americans to protect against nuclear war.

However, when I look at this picture, I think of my home, and oddly this scene is extremely nostalgic to me. I’m saying this because I want you to realize how intimate we all are with violence. Every single one of us. The violence we see around us, the militarism, that is something very easy to take for granted.

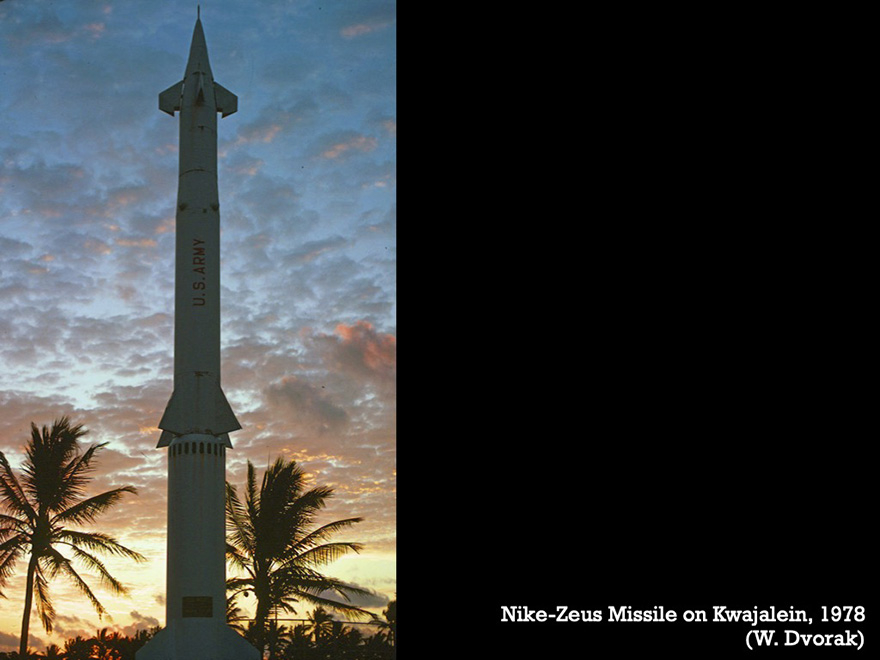

Here’s another example. This missile is a Nike Zeus missile. My father took this photograph in 1978. This missile was located on our baseball field, treated like a monument. It was a real missile but honored like this as an icon. This was like a very familiar sight for me as a child. I remember hugging it, just as part of my friendly hometown landscape. This contradiction is quite interesting if we think about it. As a child in that space, I never was asked to think deeply about this violence or why this horrifying object was even there.

In the Pacific

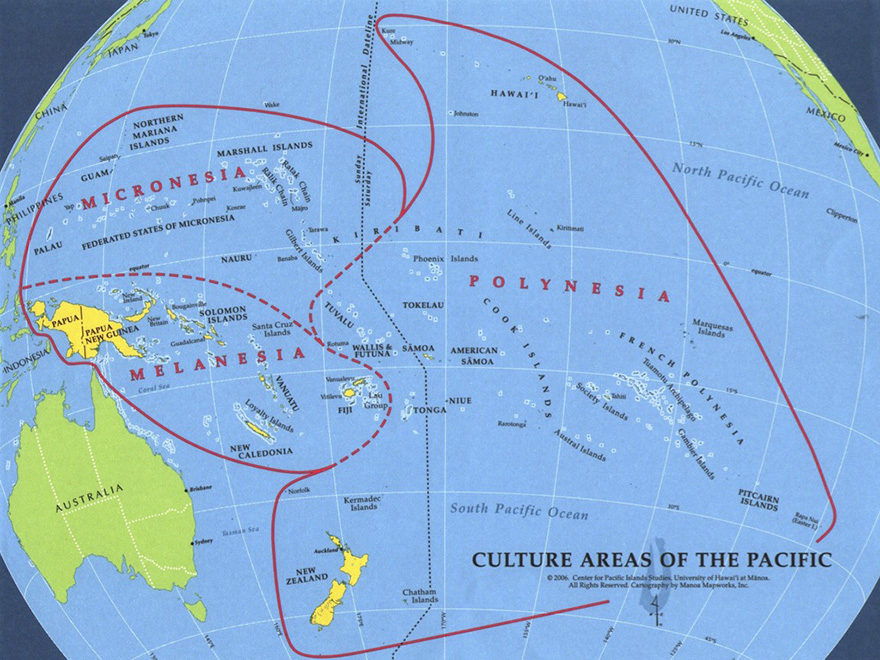

Here is the map which shows the three “nesias”. These regions are actually very, very big. European colonists came to this area, explorers like Captain James Cook. And they came and they named these regions based on their own stupid observations.

In some cases, these categories make sense. So, there is some truth sometimes. As you see one of the largest spaces of ocean. “Poly” means “many”.

Melanesia is in the southwest part of Oceania. Many, many islands in this area, very, very ancient settlement of thousands of years ago, much diversity and then above that is Micronesia.

Let’s think a little bit more about these names. As I said Polynesia means many. And what about other words? “Mela”?

“Black”.

These islands were categorized and named as such because of how Europeans entering the Pacific naively perceived the people from their perspectives. They noted that the people of Polynesia had lighter skin and when they went to this southwest area, they discovered that people’s skin was much darker, and therefore they named it “Melanesia.”

This is anti-Blackness. This is racism: European whiteness imposing its perception of “Blackness” onto the map.

Third category, Micronesia, is literally “everything else,”: it’s etcetera, micro, lots of little islands… However, this word is also very belittling. It’s a very negative way of talking about smallness, small, not as big as Polynesia, not as important. Small, irrelevant, negligible…

In recent years, we have noticed so many influences throughout the Pacific. The United States military is changing its approach, too. You also see Japan spending more money in the Pacific. There is a lot of international news about China in the Pacific, for example.

I made this term up. But it’s true on some level. We can look at this region from so many different angles in the Pacific and see how it could also be perceived as islands deeply influenced and desired by Chinese power, in other words, “Chinesia”.

And how about “Japanesia”?

Japanese colonialism

There are so many multiple perspectives that come together to form colonial fantasies. “Japanesia” actually has a very long history. Japan formally colonized the area of Micronesia known as the “Inin Tōchi Ryō Nanyō Guntō,” The Pacific Islands Mandate, for over 30 years.

I would like to point out, in this country that we call Japan, there is barely any museum of history space that talks about this at all. Only a little bit, if you go to the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka. And there, too, is almost no mention that Japan actually colonized these islands. It actually is missing from the story.

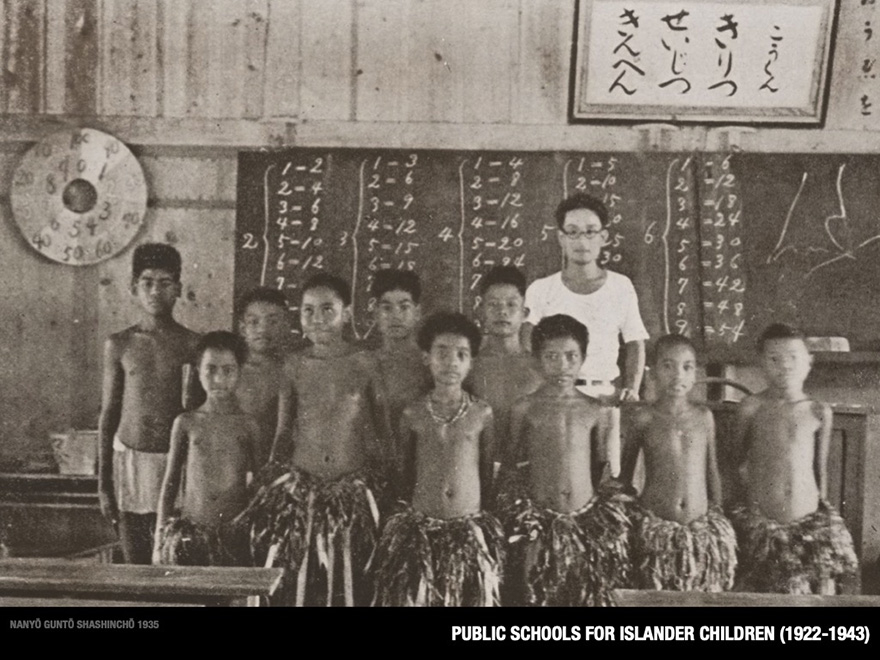

This is a picture from Palau, I believe. These are children going to school with a Japanese teacher. Many elders reminisce that they often loved their Japanese teachers, in fact.

They got pretty close to them, and they learned Japanese; they were quite fluent in Japanese. But there is something that people don’t learn at all in Japan. What people typically do in Japan when they think about Japanese in Micronesia is they usually just talk about the war that eventually broke out in 1941. They just talk about the war. There was a war. A war happened and then it was over. But what was that about? What came before? What was that story?

My purpose is not to tell you the whole story, but it’s just to point out that there was a history, there were many histories, and we need to think about them.

American liberation

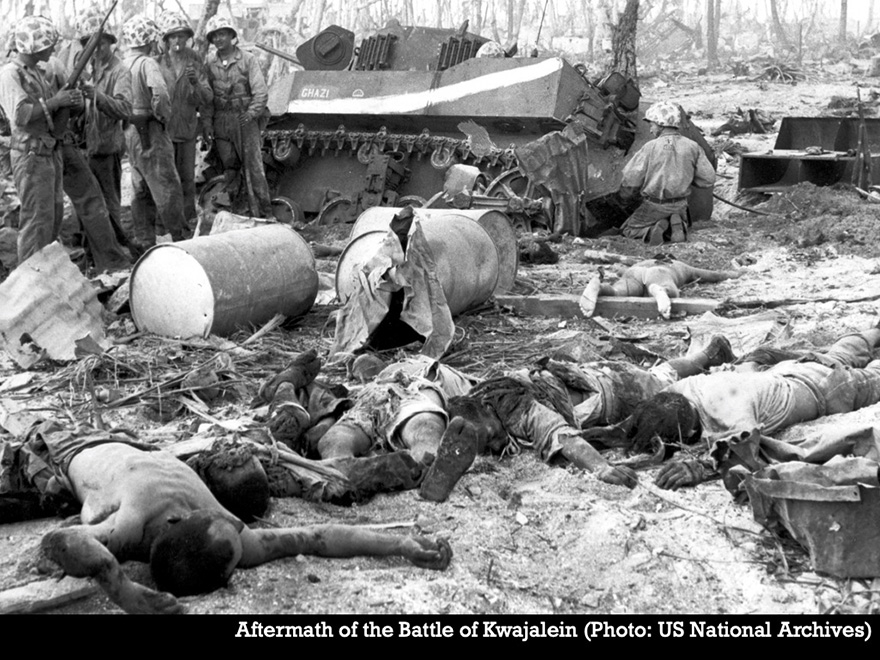

The next image I am going to show you is a little bit violent.

I grew up on island where people, American people always talked about liberation. They spoke about the American “liberation” of the Pacific.

However, the truth about “liberation” was this.

This photo appeared on the front cover of a military magazine called Yank in the United States in 1944. You see American soldiers in the background and then in the foreground you see dead Japanese soldiers and probably Korean forced laborers.

During the invasion of Kwajalein Atoll where I grew up, many, many American soldiers came. There were about four times as many American soldiers as Japanese soldiers.

Of course, for Marshall Islanders this was also extremely painful. Their land was destroyed. Their homes were destroyed. Their villages were destroyed. And everything was burnt, and no one did anything to repair the damage that was done. Neither Japanese nor Americans did anything… And to make matters worse, the Americans encouraged Marshallese people to bury the Japanese dead.

This image upsets me the most.

You have to imagine that back in those days, these people, these Marshallese people, they spoke Japanese. They saw themselves as related to Japan. They were not anti-Japanese necessarily. They were even somewhat pro-Japanese, but they were mostly unfamiliar with Americans, and yet suddenly they had to bury these Japanese soldiers, some of whom they even may have known personally.

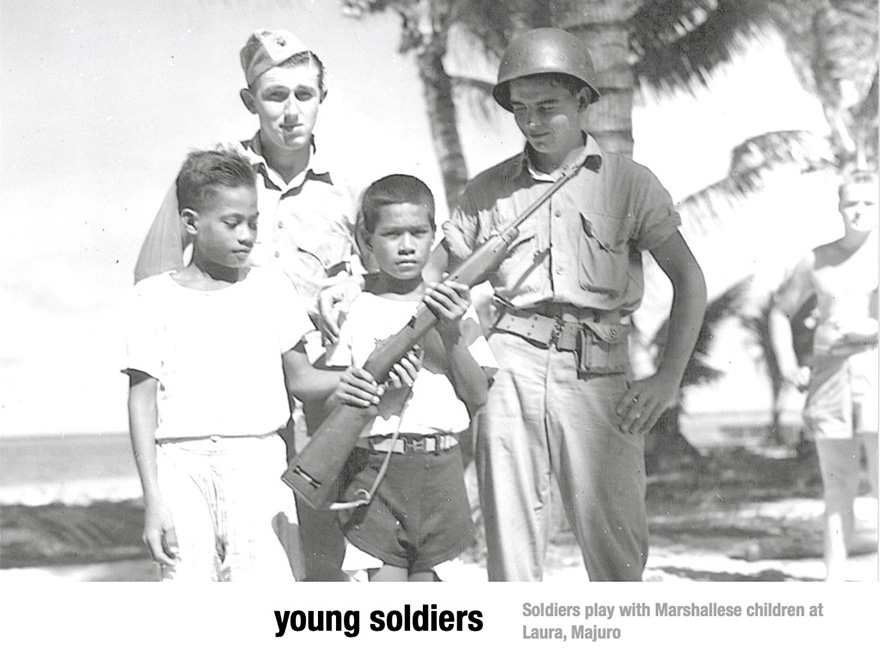

But very quickly this relationship between Americans and Marshall Islanders began to change.

These are American soldiers playing with Marshallese kids, letting them hold their guns.

Along came a very paternalistic, patriarchal new kind of masculinity in which the Americans became sort of the new heroes of the postwar that little boys looked up to. Ironically, today, for Marshall Islanders, one of the best jobs they can get is to join the U.S. Army, because of a special agreement with the United States under the Compact of Free Association which entitles them to join the US military. So, now there are actually Marshallese soldiers who have tragically died in Afghanistan or Iraq.

Bikini

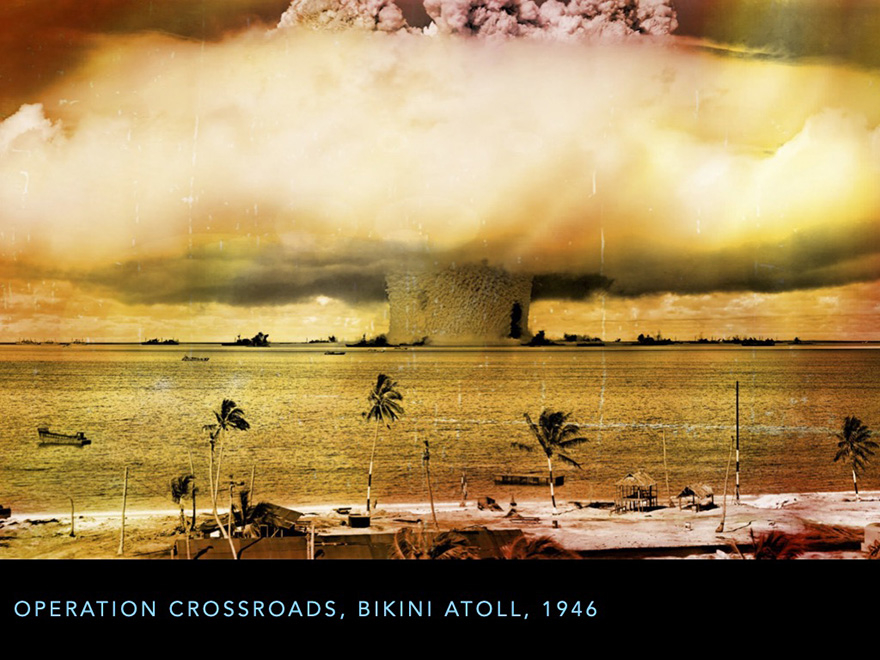

And it gets worst. But we cannot forget this. Because only one year after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, in fact less than one year, the United States began to test nuclear weapons in the Marshall Islands at two different atolls called Bikini and Enewetak.

The US Department of Energy tested 67 nuclear weapons in these atolls over the course of 10 years, between 1946 and 1958. If you add up the amount of atomic detonation over this time period, it was equivalent to one Hiroshima every day for 10 years.

This was someone’s home. The people of Bikini lent their land to the Americans because the Americans promised they would give it back. They said that they would borrow it “for the good of mankind and to end all wars.”

And sadly, today if you do a web search for the word “Bikini,” you don’t see this history or this atoll first. You see a bathing suit that is made to excite heteronormative men about the exposure of women’s flesh.

In fact, the reason the bikini swimsuit was named “bikini” is because the designer, whose name was Louis Réard, was a French man who decided that it would be very cool to name a titillating bathing suit based on how it makes a man “explode.”

What we forget when we look at the spectacle of how exciting, how explosive this all is, is that this is someone’s home, and these are real people who have been displaced and traumatized for generations.

And so, in Japan it’s significant how the experience of the nuclear atomic bombs created a new kind of memory: “the end of the war and all that came before.” And in some ways, the same is true in the Marshall Islands.

So, of this phenomenon, we can say that the new Pacific was not just the beginning of “Americanesia,” it was actually the inauguration of an ocean of “Amnesia,” about which we have all been asked to forget the past.

My point is not only that we actually forget, nor is it only that “they” want us to forget. I mean that the government of the United States would rather we truly believe that this was all only ever about liberation. And the government of Japan would rather believe the postwar has all only ever been about development and peace.

But it’s not. It’s more than that. And we also replaced these horrifying images with the commodified images of tourism, bikini swimsuits and beach vacations. The thing we need to remember is that, just like the missile that I used to play with as a child, all of this is so familiar but actually violence is hidden in plain sight.

Greg Dvorak

Greg Dvorak is professor of Pacific and Asian cultural studies in the Waseda University Graduate School of Culture and Communication Studies and undergraduate School of International Liberal Studies. Having spent his life between the Marshall Islands, the United States, and Japan, he teaches and researches mainly on themes of postcolonial memory, gender, militarism, resistance and art in the Oceania region, particularly where Japanese and American empires intersect in Micronesia. Founder of the grassroots art/academic network Project Sango, he serves as a co-curator for art from Northern Oceania in the upcoming 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Art, and has helped to advise other exhibitions such as the inaugural Honolulu Biennial. Among other publications, he is the author of Coral and Concrete: Remembering Kwajalein Atoll between Japan, America, and the Marshall Islands (University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2018).

* This talk was held at the Kyoto University of Arts on July 3, 2021.