GAT 031 Yoshitake Mika

My Evolving Role as a Curator: Part 1

As an international curator Yoshitake Mika has been involved in many projects in museums and galleries. What are the differences in the circumstances and objectives of working in museums or galleries? The following is an excerpt from a talk given on December 11, 2021.

Edited by Ishii Jun’ichiro (ICA Kyoto)

In this talk, I’d like to introduce some key exhibitions I have engaged in both museums and galleries, even private collections since 2005, as a doctoral student up to the present as an independent curator.

In particular, I’d like to reflect on the circumstances and objectives and working at museums versus galleries, including whether projects were generated by institutions or from myself, and my larger role of cultural translation in the Modern and Contemporary Japanese art and introducing it within a global context, through the organization of international touring exhibitions, catalog publications and through public programs and finally, I would like to briefly touch on my upcoming project on climate and social justice.

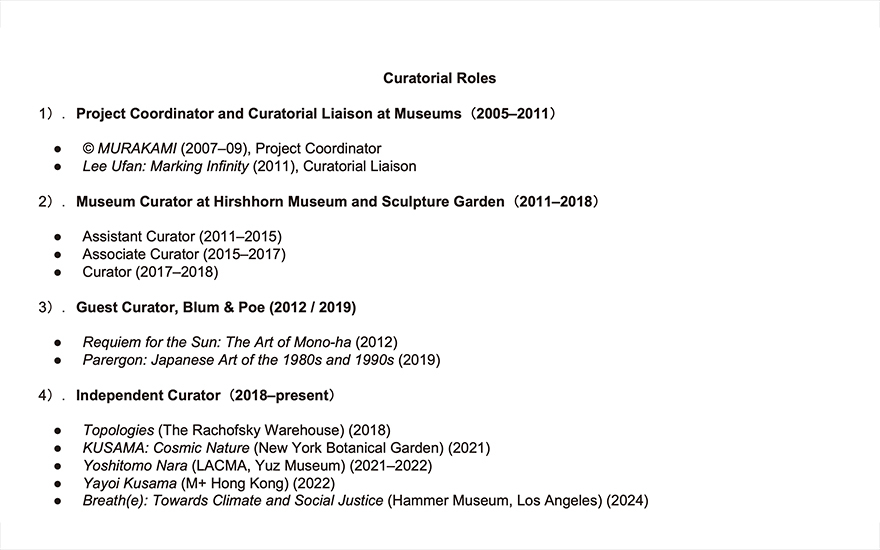

What you see here is for rough, or an outline of my exhibitions, and the roles that I have taken. In the beginning, I worked at museums as a Project Coordinator and Curatorial Liaison where I conducted my training under major curators. And then I was a museum curator myself at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden for seven years where I culminated in a major touring exhibition on Kusama Yayoi and then, I guess at the beginning and end of those years, I was a Guest Curator at Blum & Poe where I curated my most, I think well known or recognized exhibitions on “Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha” and also recently, Japanese over the 1980s and 90s called “Parergon”.

Since 2018, I have been Guest Curator for several museums, including the New York Botanical Garden, LACMA and M+, and then the upcoming one is at the Hammer Museum.

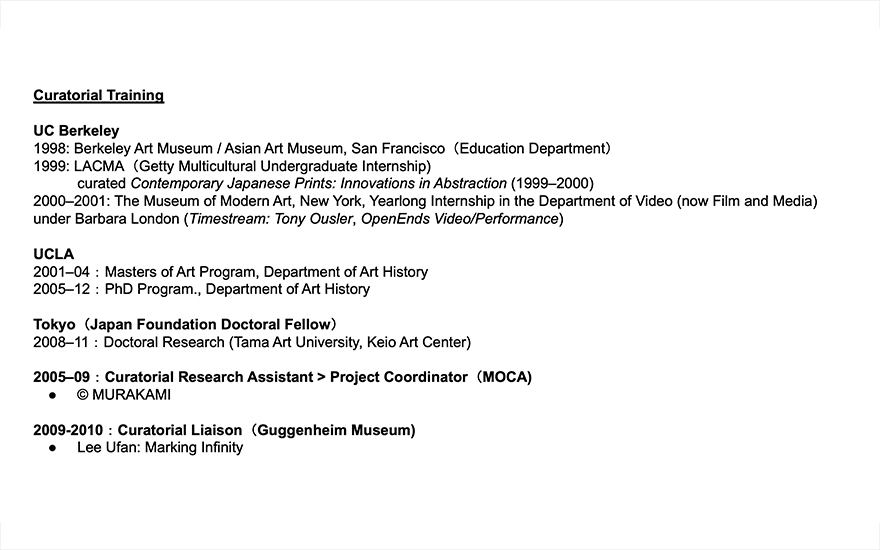

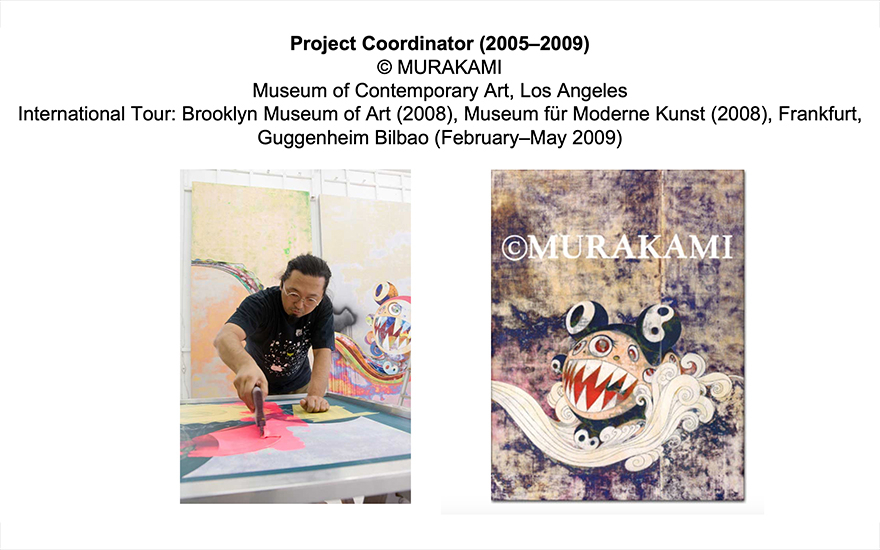

In 2001, I entered the graduate program at UCLA, where I studied art history under two advisors, Miwon Kwon and George Baker and for my graduate studies, I moved to Japan in 2008 as a Japan foundation fellow, and conducted my research at Tama Art University and Keio University, where they had the Mono-ha archives. But while I was in graduate school, I started working at MOCA where I was hired to work on the retrospective of copyright Murakami.

At MOCA, I was hired to be the Curator Research Assistant for Paul Schimmel, who is a major curator, who had included Murakami Takashi in a group exhibition called “Public Offerings”. He positioned Murakami as a new type of artists for the 21st Century, a hybrid of creator, entrepreneur and cultural ambassador and the retrospective traced Murakami’s global impact socially, culturally and art historically. I should say that I was hired, because I was not a big Murakami fan. I was more interested in Murakami as a thinker, and his knowledge of contemporary Japanese art, but then, I learned, I got to know him and I actually really enjoyed working with him very much.

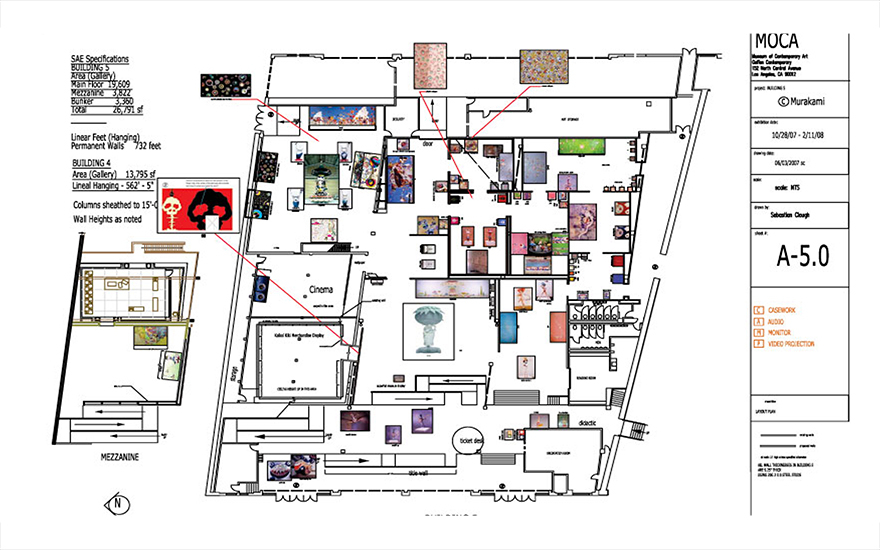

This is a floor plan of the exhibition, which included over 100 works and covering a span from 1989, the late 80s to 2007.

«Signboard Tamiya» was the first work in the show. This emerged, it was very important because the concept of the show was to talk about how Murakami reveals this duplicitous structure of consumption. The marketing of difference which is Tamiya in the structure of the same and he was exposing the sign value of this commodity or the Tamiya brand.

As art historian Hal Foster has noted, we consume more than the object as such. It is the brand name that triggers our desire, the commodity as signed that becomes our fetish. He replaces the fetish of the commodity with the aura of the artist himself.

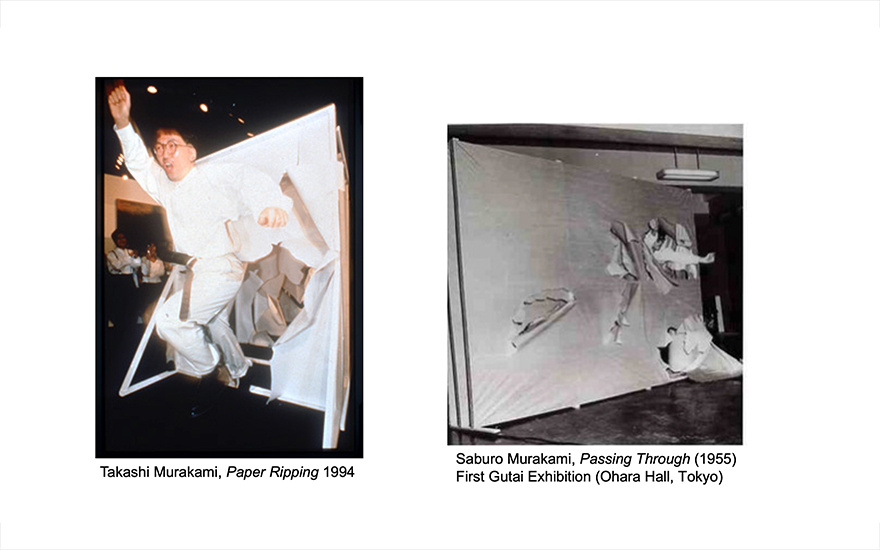

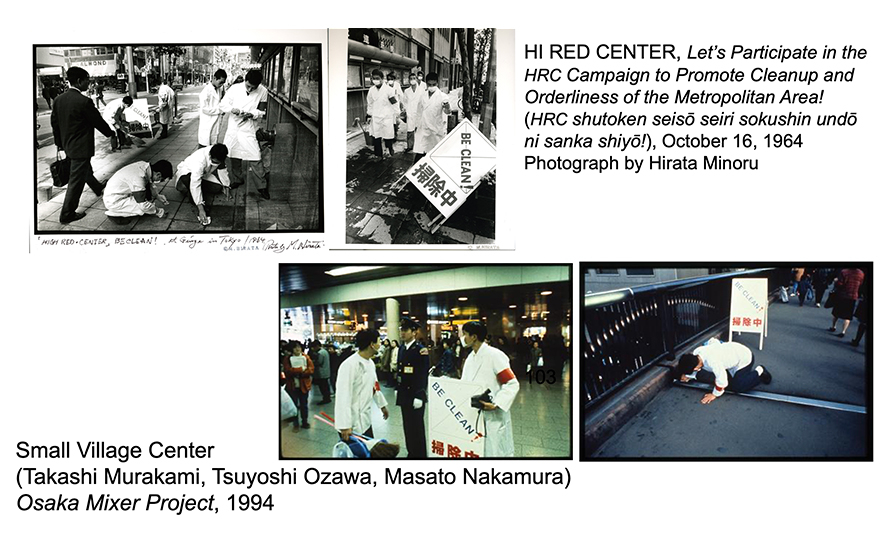

Murakami Takashi was also interested in re-evaluating the history of Japanese Avant-Garde. So, he would do these performances of, in Japan very famous artists are like Gutai, and re-performed them in a parody. This was part of his aesthetic of nonsense, which is very key term for him.

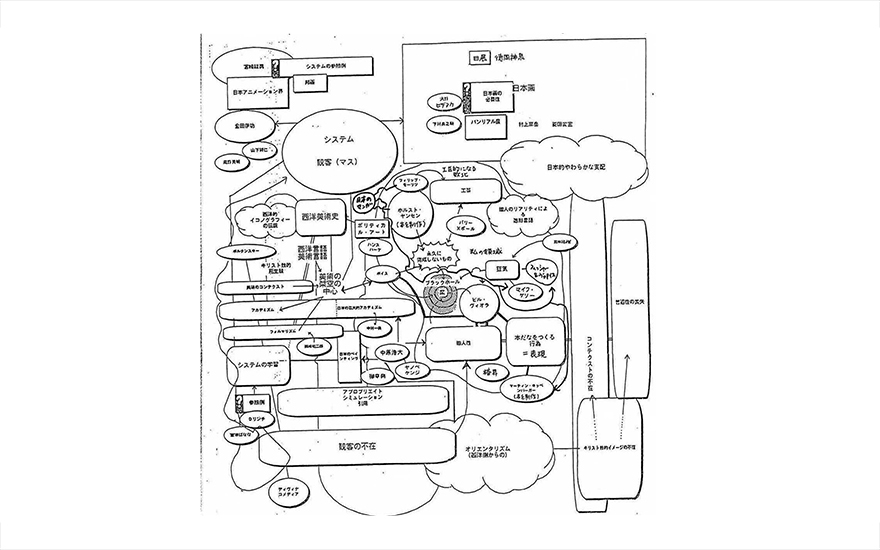

This is his diagram from his dissertation, which was called the meaning of the nonsense of meaning and I won’t go into it too much, but it’s very relevant to the postmodern subject and the emptiness that you find in meaning at the time.

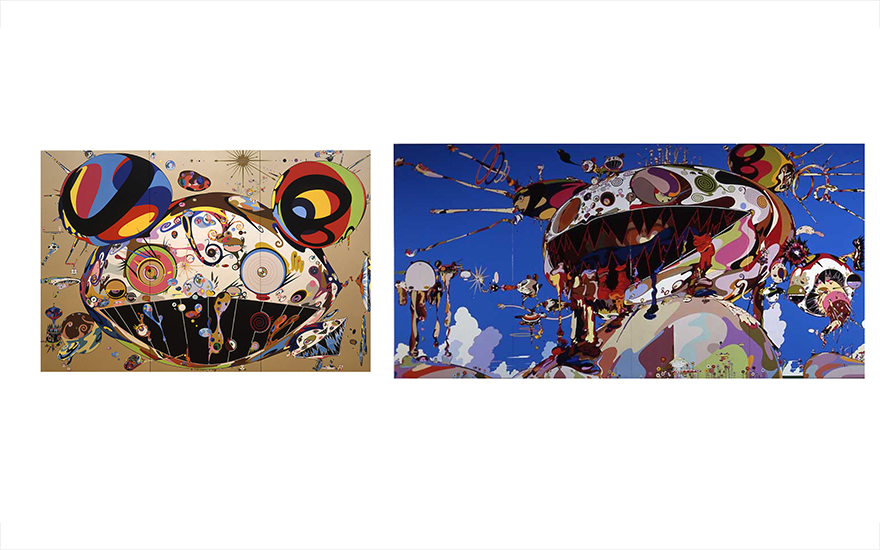

The DOB character, which you see in a lot of Murakami’s work, is derived from a phrase “Dobozite, Dobozite, Oshamanbe”. So it’s a language. It’s not a character so much as this anonymous language that is drawn from 1970s Japanese Manga. It’s kind of nonsensical.

And then we track the evolution of DOB and into this conduit or this subject that basically it is an excess, it’s like this product of excessive consumption.

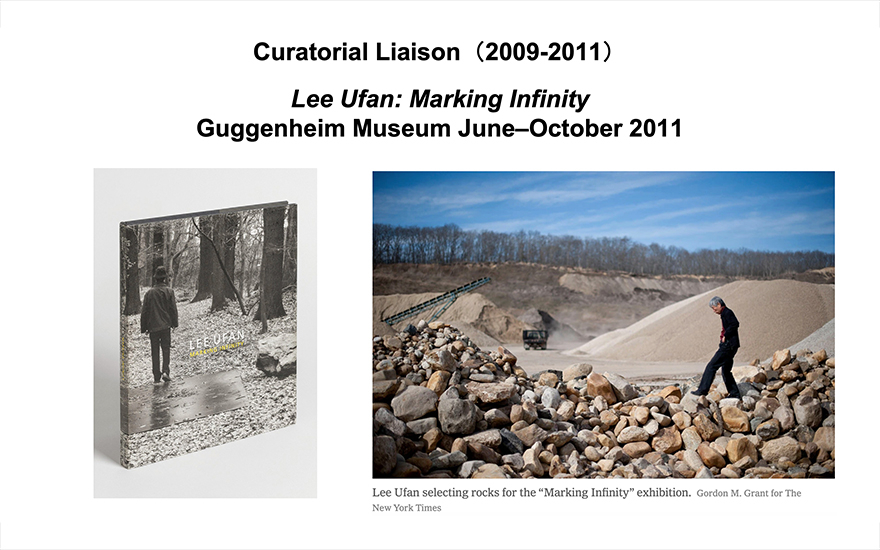

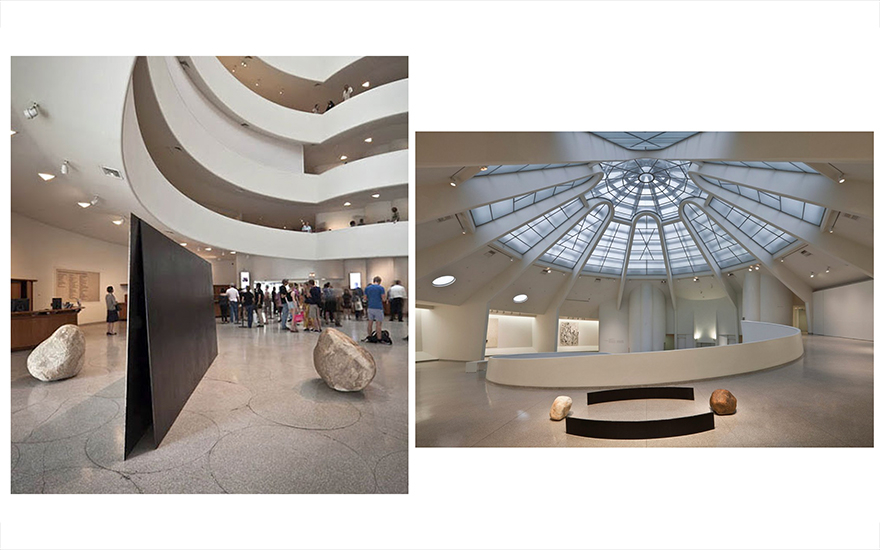

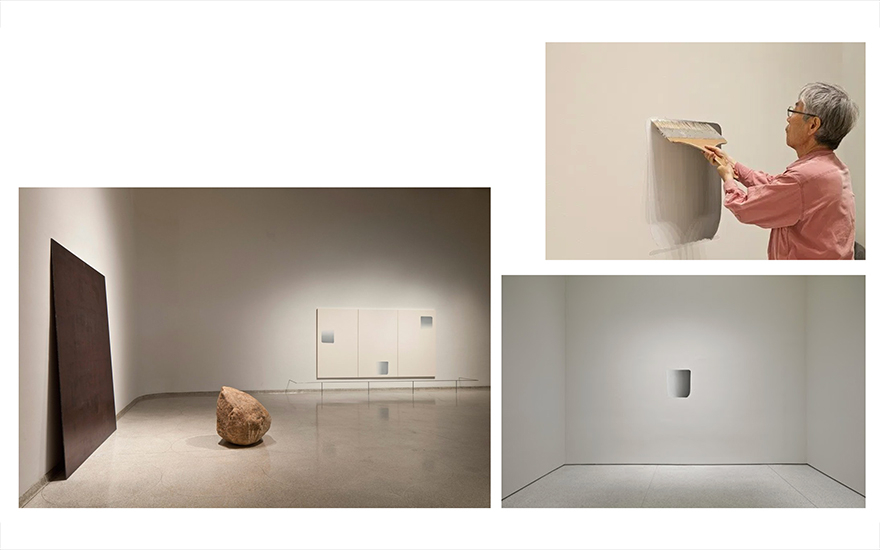

Next, a very different kind of show was “Lee Ufan: Marking Infinity”, which is organized by Alexandra Monroe.

Here I was positioned between the artist and the museum. So here, it was a curatorial training and all aspects of exhibition making, as well as translating for the artist at all on-site meetings, and providing original research and loan work for the for the exhibition and catalogue.

Through this exhibition, I learned, I worked so closely with Lee that I work and I went to his studio every weekend, and I learned how he thinks as well as installs his exhibitions, which is a very important aspect of Mono-ha.

Next, my experience at the Hirshhorn Museum was basically it was seven years. I organized many, many collection shows, which actually was a wonderful way to learn about collection building and recontextualizing collection through the lens of nonwestern art and I also was able to acquire a lot of Japanese works into the collection.

I also worked on as a coordinating curator for Ai Weiwei, “According to What?” we just curated by Kataoka Mami, and this is where I met her the first, and it was formidable experience for me.

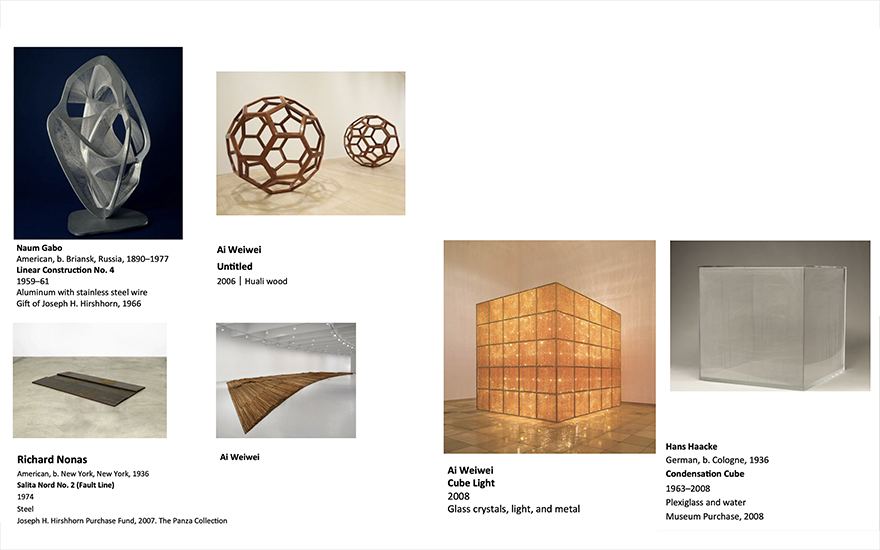

We also were able to make a dialogue with the collection, as well as Ai Weiwei’s work. So, it was a great opportunity to create an inter or transnational dialogue with Ai Weiwei’s work and his references to some of the histories of, for example, Naum Gabo, which is Russian constructivism to Hans Haacke, which is this more institutional critique minimalists work and then, also Richard Nonas who was Post Minimalist Artist.

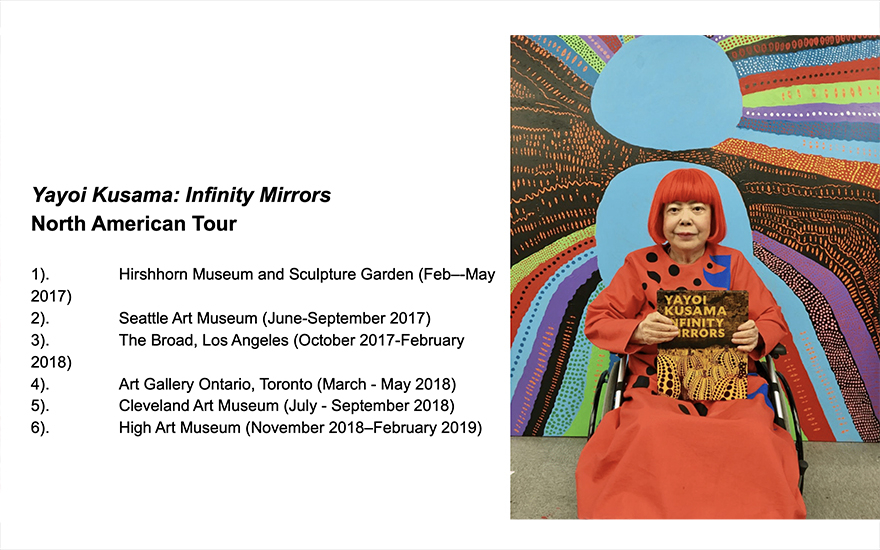

The final exhibition that I organized at the museum was Kusama “Infinity Mirrors”. This was a show that the current director, Melissa Chiu wanted to have a show just on Kusama «Infinity Mirror rooms», but I actually countered that and said, well, what about the genealogy of Infinity, because there had been so many customer shows.

We basically negotiated and so, we ended up doing a show on Kusama, but it was to historically contextualize the «Infinity Mirror rooms».

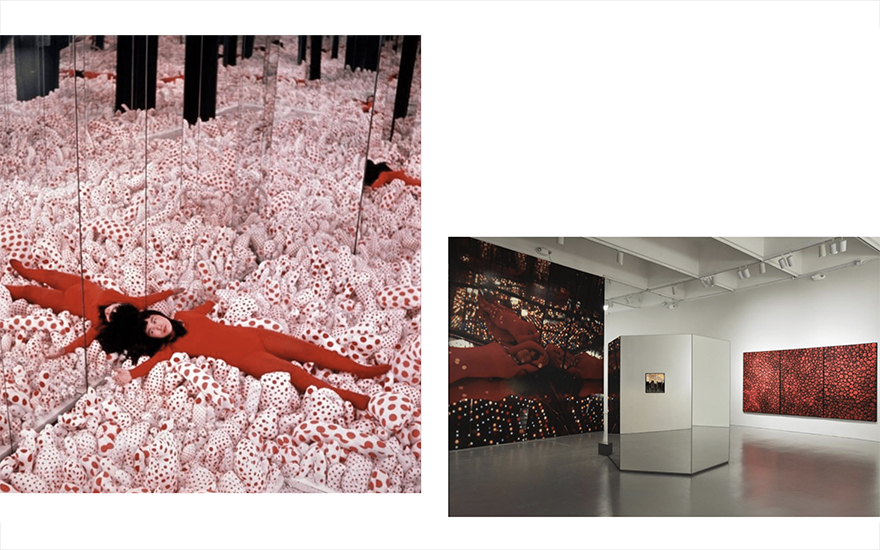

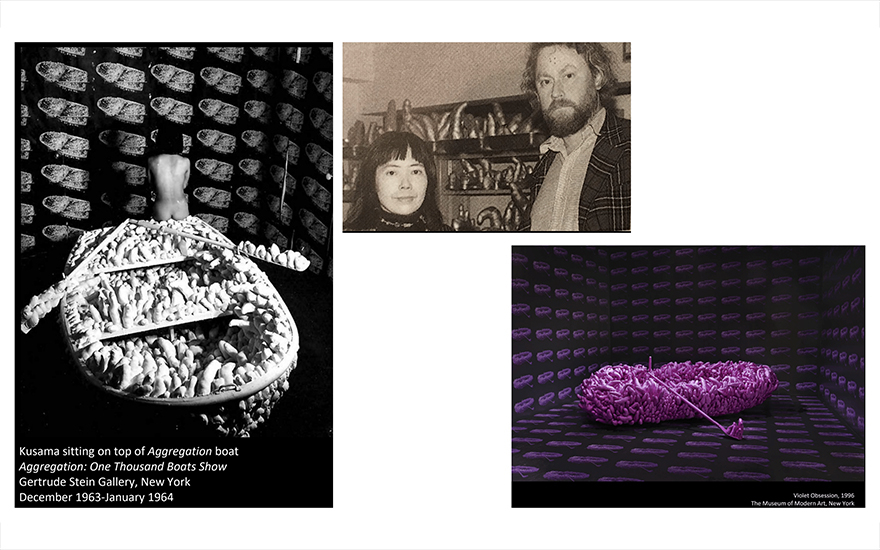

The show really began as a narrative arc of the «Infinity Mirror rooms». And the artist has produced over 20 distinct mirror rooms since 1965 and this is the first one called «Phalli’s field».

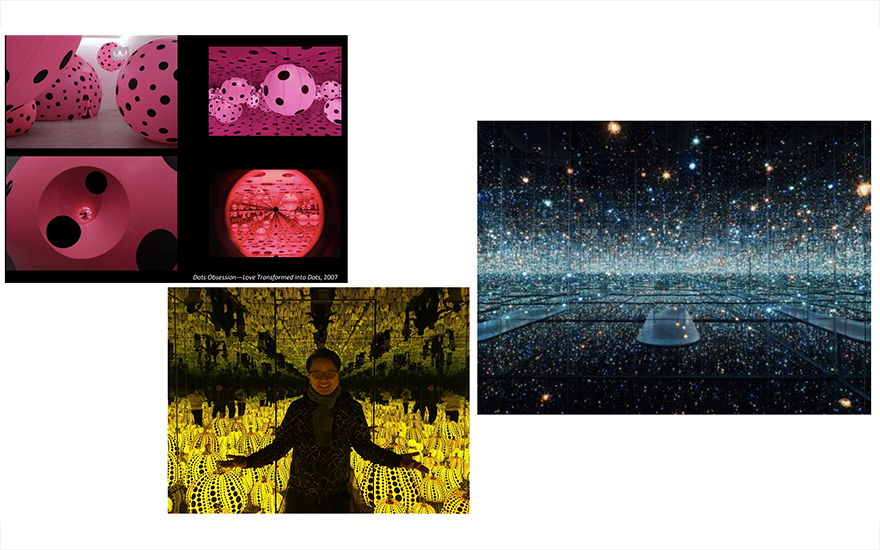

As well as the 10 peep show like chambers, which is the one on the right is «The Love Forever». We wanted to include this idea of perception, and something that was very important for the experience of these rooms. We had a big mural of Kusama inside, one of the Mirror Rooms, «The Love Forever» and so it’s kind of like a skin where you see the interior and the exterior. And then, we had six mirror rooms, which were compounded by various other artworks.

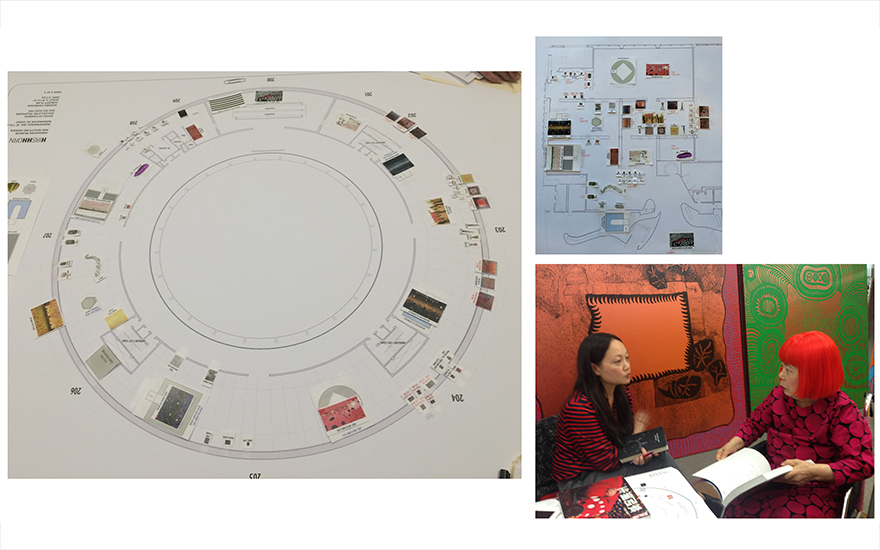

I worked actually closely with her on this floor plan. This was my first meeting, and the show travelled to six venues. Each time I had to get approval, but – so this the floor plan for the exhibition, and you can see some of the artworks that are layout, it’s roughly chronological.

The concept for the show begins with this idea of infinity, which is this trajectory of efficiency. She was painting these gesture marks over and over again and then she started to make these accumulation sculptures, which were, she was sewing and stuffing these fabric tubers. Then she discovered the silk screen process of photographically reproducing the sculptures all around in an immersive environment.

This is the, not prototype, but the beginnings of leading up to her mirror rooms.

She discovers mirrors in actually in Stedelijk Museum where there was an artist named Christian Megert a Swiss artist who was using mirrors, and this was a way for her to radically multiply the motif of the polka dot or the accumulation sculptures into infinity.

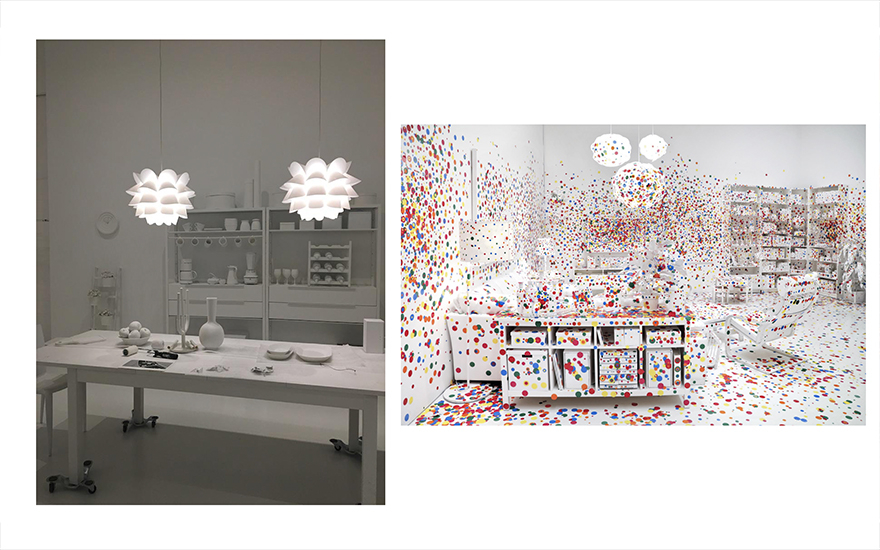

This was the final installation of the exhibition called «Obliteration room», where visitors were given stickers to obliterate the final space of the exhibition. It was supposed to relate to her philosophy of self-obliteration, which was from the 1960s, which was a part of the anti-Vietnam War movement, essentially, stripping yourself naked, and seeing each other as not other, but as equals. It was also a very powerful political stance. That was an active protest against war and also, this idea of self-obliteration is almost the opposite of the ego or the narcissism that she’s usually associated with. So, we thought it was it was kind of apropos, it was interesting to have this as a final installation, even though this is a very kind of participatory and more celebrating kind of installation.

My Evolving Role as a Curator: Part 2

Mika Yoshitake

Mika Yoshitake is an independent curator with expertise in postwar Japanese art. She earned her MA and PhD in Art History from UCLA, which culminated in the AICA-USA award-winning exhibition Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha (2012). As former Curator at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (2011–18), she organized the six-venue North American tour of Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors (2017–19). Recent exhibitions include Parergon: Japanese Art of the 1980s and 1990s (2019) at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, Yoshitomo Nara (2021) at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and KUSAMA: Cosmic Nature (2021) at the New York Botanical Garden. She has forthcoming exhibitions at M+ Hong Kong and Breath(e): Toward Climate and Social Justice at the Hammer Museum as part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: LA x Art x Science in 2024.

* This talk was held online on December 11, 2021.