GAT 038 Éric Baudelaire

MAKE, DO, WITH

Éric Baudelaire has focused his practice on those who challenge the structures of the state, constructing spaces for reflection through the medium of film. His works traverse the boundaries between documentary and fiction, prompting a reconsideration of the relationships between the individual and the state, between memory and record. The following is an excerpt from a talk held on December 26, 2022.

Edited by Ishii Jun’ichiro

* In his talk, Éric Baudelaire introduced three of his works that reflect his approach as an artist. (Due to space limitations, this article focuses only on the first project).

The title of the talk and the title of the workshop is “Make do with” which means really making work, but also making with, which means collaboration. To make do with is really about figuring out a way to live in this world or to work with the events of the world.

My very first project as an artist was in a place called Abkhazia, which is an unrecognized country in the former Soviet Union. I started working as a photographer, and in the year 2000, I hired as my assistant a young man called Maxim Gvinjia.

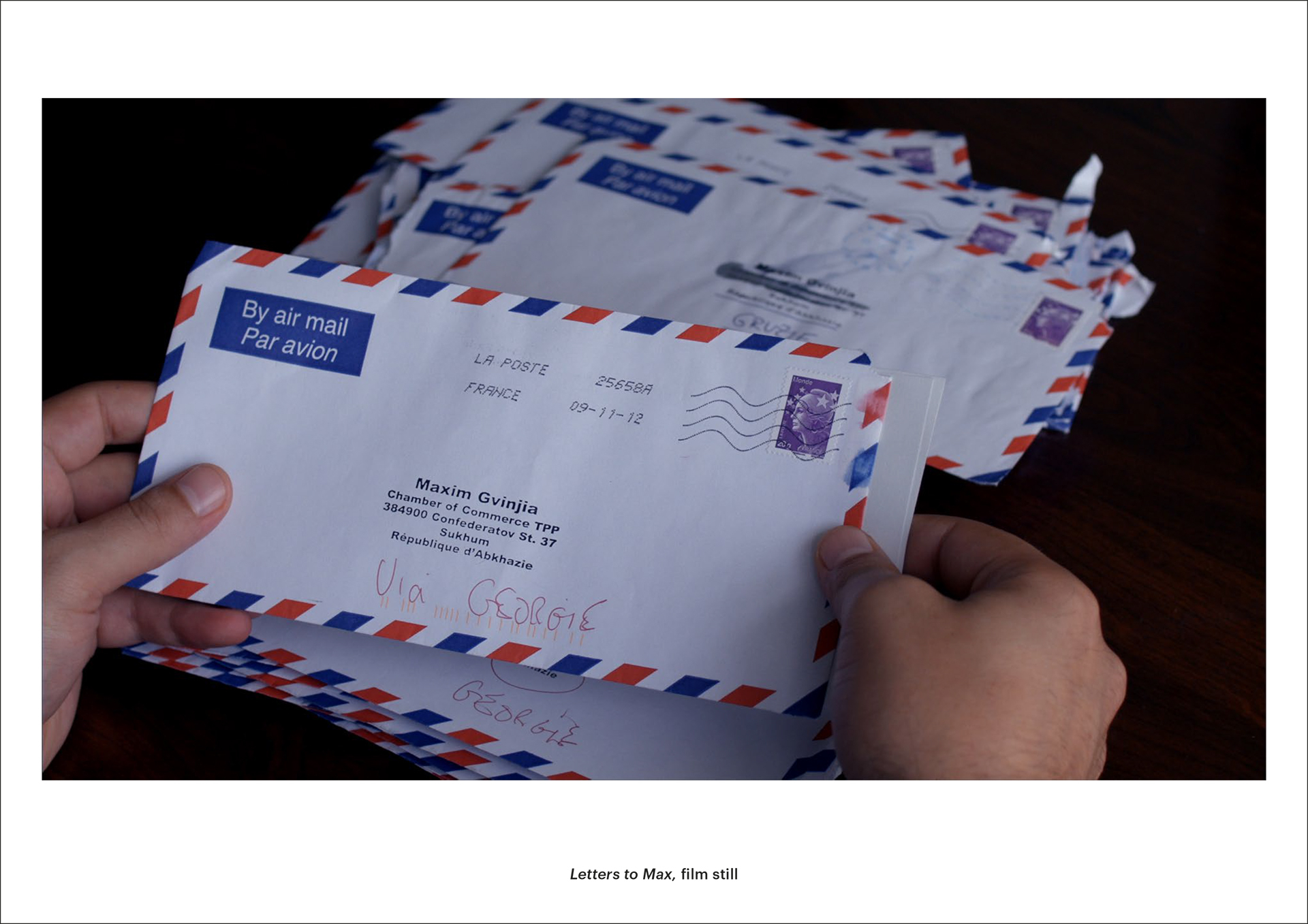

Maxim was working at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of a country that doesn’t have foreign relations. So, it’s a paradoxical job. Over the years, I came back many times to Abkhazia, and every time Maxim had a more and more important job in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs until eventually he became Minister of Foreign Affairs. But because Abkhazia does not exist as a political entity recognized by France or the European Union, I thought that if I wrote Maxim a letter, a postal letter, that this letter would not arrive because nobody would know how to get this letter to him. I began writing letters to Max thinking that they would come back to the studio, and I would make a sculpture with a big pile of letters that had been returned to the studio.

But the letters arrived, and so Max received about 65 letters over the course of half a year, and he answered these letters by recording his voice. Then I went to Abkhazia and I filmed a film about what it means to be an unrecognized state, what a state is, and sort of looking at this idea that a state is a collective fiction that works when everybody believes it and recognizes it. It doesn’t work when it is not recognized, the fictional nature of statehood becomes very obvious in this condition of non-recognition.

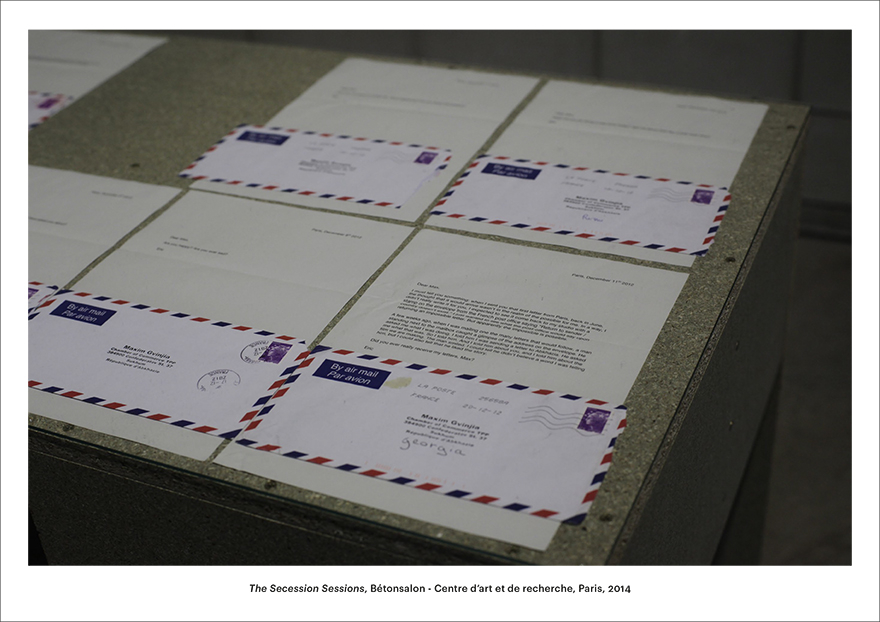

This film is an hour and forty minutes, so it’s really a cinema film. But at the same time, I’m working in between two spaces, which is the space of contemporary art and the space of cinema. The films circulate in some film festivals to be shown in movie theaters. When I show them in an exhibition context, I try to expand beyond the projection of the film.

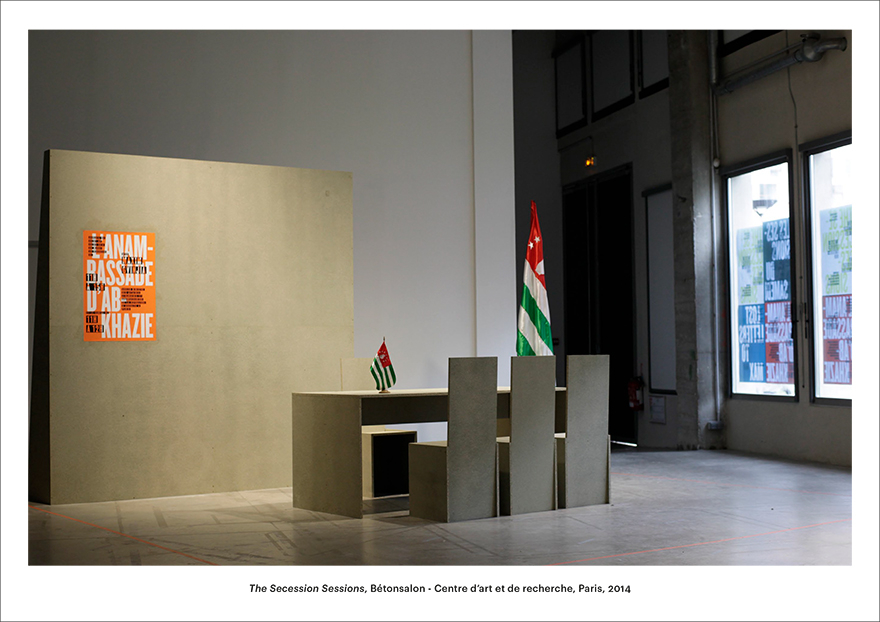

This is the exhibition at the art center in France called Bétonsalon. You can see there’s a desk here with an Abkhaz flag. What this desk is, is it’s something I call the Anembassy of Abkhazia. It’s not an “Embassy”. It’s an “An-Embassy”. I don’t know how you can translate that.

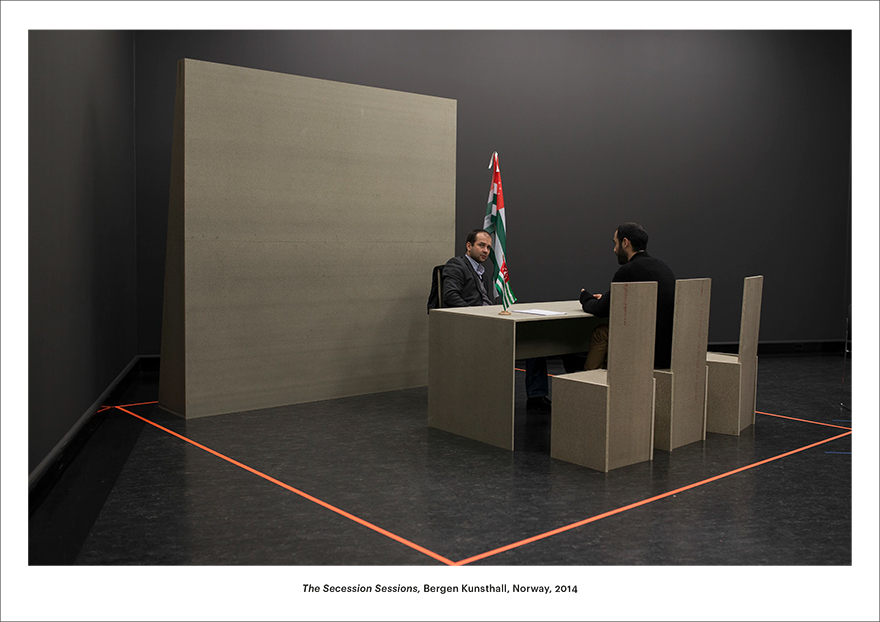

Max is no longer working as Foreign Minister. He’s just a private citizen. When I do an exhibition, I asked the art center to invite Max to occupy this office, to meet people, to have discussions. These are private encounters with Max that are not recorded or documented.

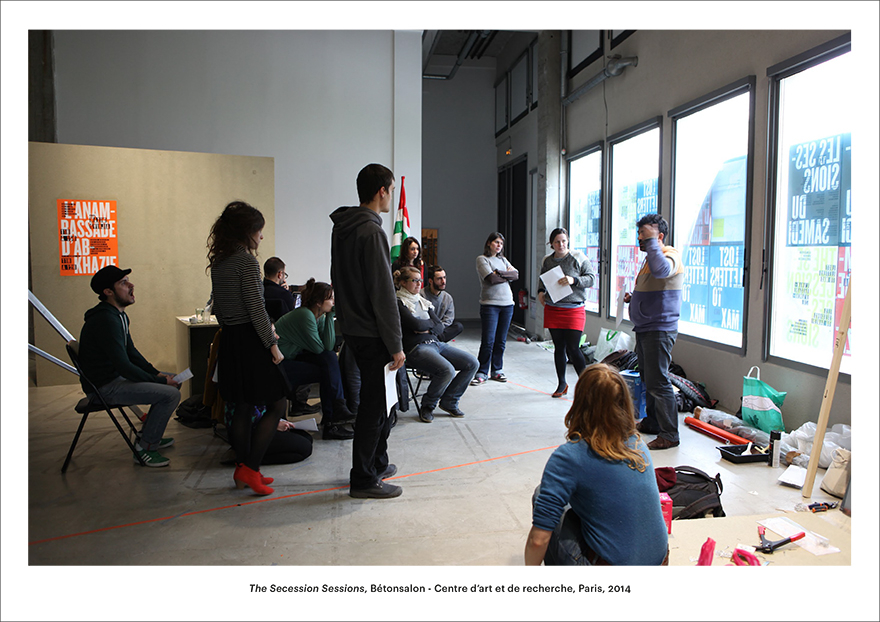

It’s just a series of private discussions with the man who used to be the Foreign Minister of Abkhazia. We also invite other people every week on Saturday, we invent a new situation that changes with every exhibition. These situations involve the public and are an extrapolation of some of the ideas that are treated in the film and in the exhibition. For example, here is a Georgian artist, who fought in the war in which Abkhazia became an independent country. He’s coming into the art center to do a workshop and a performance as somebody who used to be the enemy of the state of Abkhazia.

Every day in the morning, it’s the Anembassy of Abkhazia, and in the afternoon, it’s a cinema and the film is shown. I used the art space in two different ways during a given day. In the morning, it’s in an Anembassy, in the afternoon, it’s a cinema. On Saturdays, it’s a place of collective discussion.

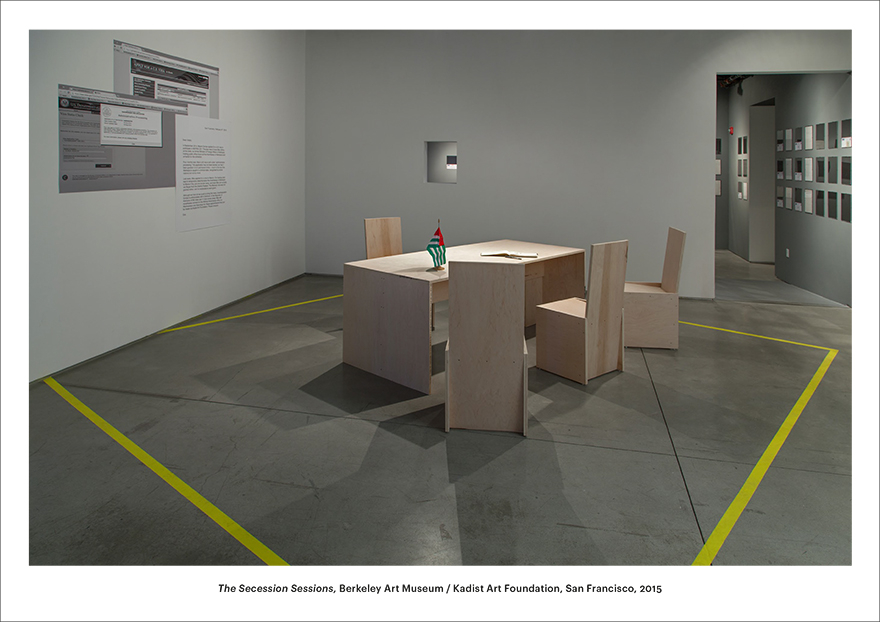

This is the Anembassy at the Kunsthalle in Bergen in Norway, and this is the Anembassy in San Francisco. But as you can see, Max is not present here because the United States refused to give him a visa.

So, we had to find a way to have Max be present in the exhibition without being physically present. People who visited the show would write down questions in a notebook, and then Max would respond by sending little short videos to the people who asked him questions. That’s how we were able to have the Anembassy function despite the political situation of not receiving a visa.

Usually, I’m in the position of being in a white cube and trying to show films, which is a bit of a contradiction because a film wants to be in the dark. At the Sharjah Biennial, which was curated by Eungie Joo, I had the chance to do the opposite, which is instead of putting a film in a white cube, I made an exhibition in a theater.

Here, the Anembassy is in the audience, and the letters are on the stage. When it becomes a movie theater, it’s very simple.

These are some examples of discussions that we had on the weekly public program. The first one is about reinventing the state, and it’s a discussion between philosopher Alain Badiou and philosopher Pierre Zaoui.

I also invited a sociologist to talk to us about the small ways in which the state manifests itself in our daily lives through the papers that it gives us, the taxes that we pay. These very small gestures which become the physical, the space where we interact with the state because otherwise the state is a very abstract thing.

Here, I wanted to show the very concrete nature of statehood. We always think of secession as something that happens in faraway places. Ukraine, the former Soviet Union. In the show in San Francisco, we invited an American secessionist party from the Pacific Northwest, a group of people who want Northern California, Oregon and Washington State to separate from the United States, and we had a discussion about what this would mean.

We also looked at the history of black separatism in the United States to sort of make this question of secession not an exotic question, but something that has deep roots in most countries.

Éric Baudelaire

Éric Baudelaire is an artist and filmmaker based in Paris, France. After training as a political scientist, Baudelaire established himself as a visual artist with a research-based practice in several media ranging from photography and the moving image to installation, performance and letter writing. His work probes a reality shaped by the systems of representation that structure contemporary societies: political, judicial, economic and informational constructs.

His feature films include: A Flower in the Mouth (2022), When There is no More Music to Write (2022), Un Film Dramatique (2019), Also Known As Jihadi (2017), Letters to Max(2014), The Ugly One (2013) and The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi and 27 Years Without Images (2011).

Baudelaire has had monographic exhibitions at Spike Island, Bristol, Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, Centre Pompidou, Paris, the (formerly known as) Witte de With, Rotterdam, the Fridericianum, Kassel, the Beirut Art Center, Gasworks, London, and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, and has participated in the 2017 Whitney Biennale, the 2014 Yokohama Triennale and Sharjah Biennial 12, Mediacity Seoul 2014, and the 2012 Taipei Biennial. In 2019 Baudelaire was the recipient of a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, and the Prix Marcel Duchamp.

* This talk was held at the Kyoto University of Arts on December 26, 2022.