GAT 039 Brett Littman

Isamu Noguchi:The In-Between: Part 2

Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988) is regarded as one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century. Brett Littman, who served as Director of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum from 2018 to 2023, offers an interpretive framework that reads Noguchi’s practice through the concept of “The In-Between.” The following is an excerpt from a talk held on April 18, 2023.

Edited by Ishii Jun’ichiro (ICA Kyoto)

to the “Isamu Noguchi:The In-Between: Part 1“

Part 2: Sculpture, Ceramics, Drawing, and Design

Let’s switch gears. I want to now talk about some specific bodies of work.

«Undine (Nadja)» 1926

Photo courtesy of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

Noguchi was primarily trained as an academic sculptor, figurative sculptor, and this is a piece from 1926 called «Undine (Nadja)», which is a portrait of a Russian dancer that was one of his girlfriends at the time. It’s a piece I’ve never physically seen, but we know that it still exists.

In order for Noguchi to make money in the 1920s, Noguchi had to do portrait busts. He had to do portrait plaques. What that allowed him to do was to really interface with a very wide variety of New York intelligentsia, philanthropists, other artists. He called it “busting heads” or “cracking heads,” and he really hated doing it. It was not something that he enjoyed, but it was the only way for him to make a living in the early days of his career.

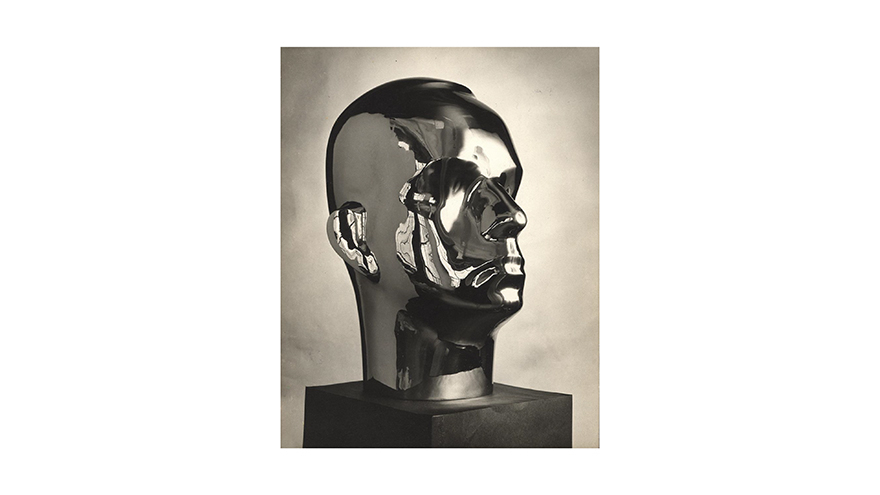

«R. Buckminster Fuller» 1929

Photo courtesy of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

This is probably one of the most famous of his portraits, early portraits of Buckminster Fuller. This was in 1929 after they had met in 1928. All in aluminum. It is a very powerful portrait, and actually, Buckminster Fuller really loved this portrait.

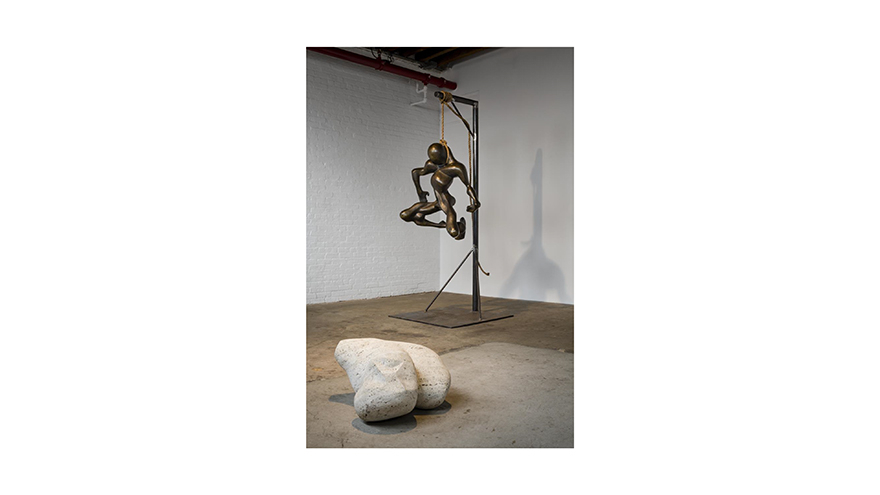

Probably one of Noguchi’s most complex and most difficult works – «Death (Lynched Figure)» from 1934, commissioned by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

«Death (Lynched Figure)» 1934

Photo courtesy of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

This piece was originally in an exhibition curated by a black curator about images of lynching. Noguchi placed it in a commercial gallery first and it was removed from the gallery. It was too powerful.

Later, he tried to place it again in another commercial show, and it was removed. We’ve kept it in our collection. It is a piece today that requires a lot of context, particularly in the United States. It is a very powerful, difficult piece to exhibit.

The next body of work that I want to talk about is Noguchi’s relationship to dance. Noguchi worked with Martha Graham starting in 1935, designing sets. He designed more than 40 sets for Martha Graham, several sets for Eric Hawkins dance group, and also sets for George Balanchine.

Dance and scenography are incredibly important aspects of the Noguchi’s story. I think the more that I’m looking at the dance sets, the more I’m beginning to understand his relationship to the body and the body’s relationship to sculpture in space.

«Frontier» 1935

Photo courtesy of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

This is the Noguchi set for Martha Graham’s piece called «Frontier» from 1935. It is a little bit difficult to know with Noguchi, whether or not he had seen No theater earlier in the 1930s in his trip to Japan or if Martha Graham kind of turned him on to the No theater because she was also very interested.

But Noguchi sets, and particularly this one is the most reductive way in which you can use sculptural space to define the delimiting aspects of the stage, and very much I think in the tradition of No theater and thinking about how one can with two ropes and a piece of fence create a very expansive vista.

Noguchi also worked in wood. This is, again, a body of work that is very little known. Sadly, all the images that I will show you, which are sculptures made in the late 1920s, we don’t know where they are and whether or not they still exist. We only have photos.

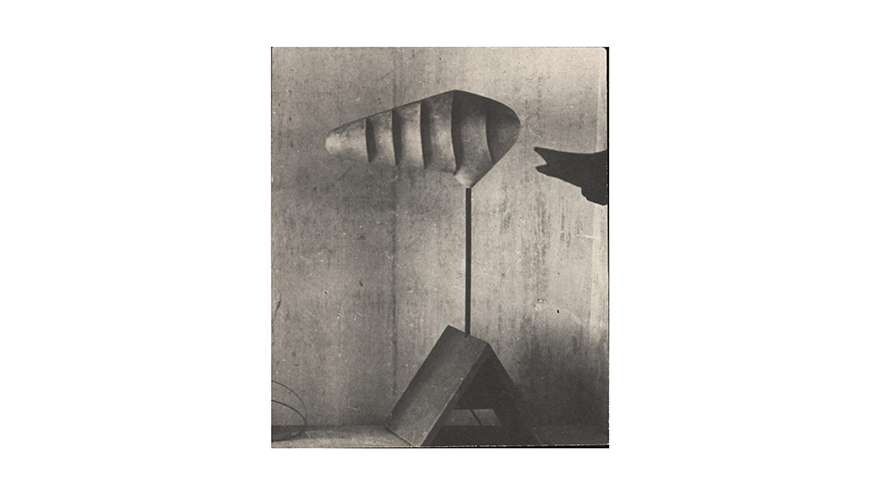

«Musical Weathervane / Lunar Weather Vane» 1933

Photo courtesy of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

These works, of course, are made post the Brâncuși era, Noguchi’s interface with Brâncuși, and they are a pretty full expression of his first forays into abstraction.

When he comes back to New York, he goes right back to making figurative work. These don’t quite stick, but maybe wood allowed him to be a material that he could work with that was relatively inexpensive, that he could kind of play with.

The next body of work I want to talk about are ceramics, which are by far the most Japanese. Noguchi only made ceramics in Japan in 1930, 1950, 1951, 1952. So, he really loved the earth in Japan, and he felt that Japan was the only place that he could make ceramic work.

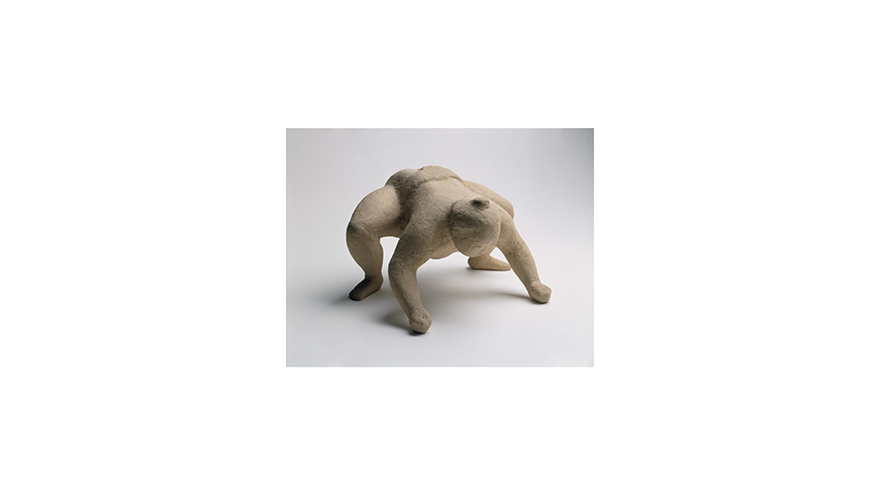

«Tamanishiki (The Wrestler) (Sumo) » 1931

Photo courtesy of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

«My Mu» 1950

Photo courtesy of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

This piece is called «Tamanishiki (The Wrestler) (Sumo) » 1931, «My Mu», 1950. This is made at the studio in Kita Kamakura that he lived in with his wife for a short marriage to the Japanese actress. He was very active in the studio between 1950 and about 1952.

Noguchi was not someone who often drew. He definitely did not draw his sculptures. However, there were bodies of work that he did work on in drawing.

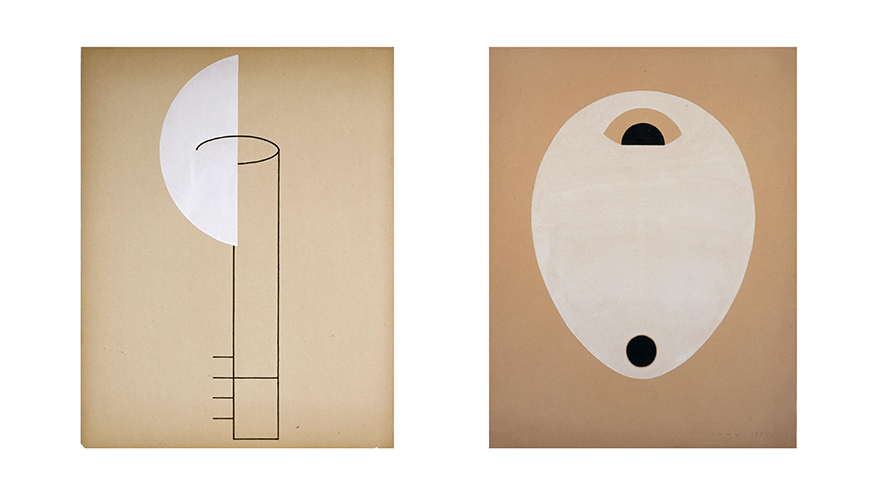

«Paris Abstractions» 1928-1929

Photo courtesy of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

We call these the «Paris Abstractions» made in 1928-1929 very much related to the early wood sculptures that I showed you. Noguchi made about 150 of these. The museum owns about 100. They’re quite interesting, very deeply influenced by Brâncuși.

The next group of objects I want to show are design, and I’m going to go through this relatively quickly. However, I want to say that Noguchi’s feeling about industrial design and design in general is that it was always under the question of what is sculpture. He did not view these activities as separate. Everything was holistically together. When he approached the design object, he always thought about it in sculptural terms.

The first known design Noguchi object is the «Hawkeye Measured Time».

«Hawkeye Measured Time» 1932

Photo courtesy of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

It’s basically a kitchen timer/egg timer, done in 1932. Many people say that this piece is probably related to early Jomon funeral sculptures, and also it reminds people of the Hiroshima Memorial that he did design for Tange, this kind of mound form. But it is a commercial design and it is something that today, probably 20 years ago, you could find this on eBay for about $10. Today, it’s about $20,000. People have kind of gotten hip that this is a Noguchi thing.

The next design that Noguchi does is the «Radio Nurse» for Zenith. This was designed in 1937 after the Charles Lindbergh baby kidnapping. It’s the first two-way baby radio, so you would have a speaker in the baby’s room.

«Radio Nurse for Zenith» 1937

Photo courtesy of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

If there was something that was interrupting the baby or the baby cried, you could hear it in your room. I mean, today, we probably have a teddy bear with a camera as eyes, you know, looking at nannies and things like that, but this is really the first thing that we have for a two-way radio for baby protection.

Noguchi started making a series of sculptural tables, unique tables as early as about 1937 for rich collectors who were interested in having these unique objects.

«Table for Conger Goodyear» 1939

Photo courtesy of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

This is the «Conger Goodyear Table». Conger Goodyear was the Chairman of the Board of the Museum of Modern Art. This object is actually probably right now one of the most expensive design objects ever sold.

It was sold for about $4.5 million at auction about 10 years ago, and it is a one-of-a-kind sculptural table, which of course led to Noguchi’s design for the «Coffee Table», a more democratic version of the «Conger Goodyear Table» that he designed for Herman Miller in 1944.

«Coffee Table» 1944

Photo courtesy of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

And of course, the «Akari» lamps, which were really started because the Mayor of Gifu invited Noguchi to come to Gifu, a town that was struggling after the war because the traditional paper lantern businesses were kind of collapsing, and he asked Noguchi to think about how he could revive the lantern business.

«Akari» 1952-present

Photo courtesy of The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum

Noguchi had the brilliant and strange idea that it was the first time that anyone thought of it to put an electric light bulb inside of a paper lantern. Akaris are still made by the Ozeki family (Ozeki & Co., Ltd.), and there are probably 197 different versions of Akari still in production today.

to the “Isamu Noguchi:The In-Between: Part 3“

Brett Littman

Brett Littman held the position of Director at the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum in Long Island City, New York from May 2018 until June 2023. He was Executive Director of The Drawing Center from 2007–2018; Deputy Director of MoMA PS1 from 2003–2007; Co-Director of Dieu Donné Papermill from 2001–2003 and Associate Director of Urban Glass from 1996–2001.

Littman’s interests are multi-disciplinary: he has overseen more than 150 exhibitions and personally curated more than thirty exhibitions over the last 16 years, dealing with visual art, outsider art, craft, design, architecture, poetry, music, science, and literature. He was named the curator of Frieze Sculpture at Rockefeller Center for 2019 and 2020, is an art critic and lecturer and an active essayist for museum and gallery catalogues, in addition to writing articles for a wide range of U.S. and international art, fashion, and design magazines.

A native New Yorker, Brett Littman received a Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters from France in 2017 and his B.A. in Philosophy from the University of California, San Diego.

* This talk was held at the Kyoto University of Arts on April 18, 2023.