Moving outside la chambre claire (Camera Lucida) -Takatani Shiro Topograph/ frost frame Europe 1987 )

by Shimizu Minoru

Entering the exhibition space on the second floor of the gallery, you see Topograph / La chambre claire displayed on the wall in front of you, work from the new series Toposcan on the opposite wall, and frost frames / Europe 1987 on the walls to the left and right. Thus the works are arranged so that scannings occupy the front and back walls and photographs the side walls, with mirror type k2 positioned between them. In other words, the exhibition is organized around a comparison of “photography” and “scanning,” that is, of the way of seeing represented by analog photography and the future way of seeing being opened up by the latest digital technology. Based on the supposition that the human eye is invariably prescribed by the technology of the times, this exhibition is a rare attempt to acknowledge that the era of “seeing” under the strong influence of photography has finally ended and that the era of “seeing” via the technique of digital scanning has arrived, and to come to grips with the strangeness and beauty that result from this unfamiliar way of seeing.

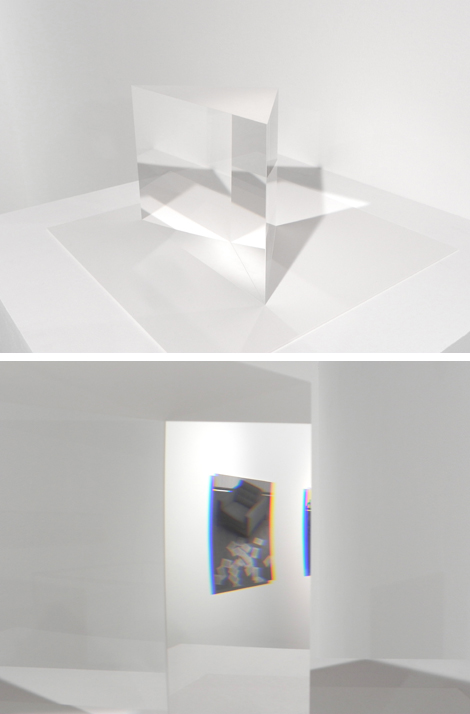

Installation view (Front Wall)

Takatani Shiro, Topograph / La chambre claire

Installation view (Facing Wall)

Takatani Shiro, Toposcan

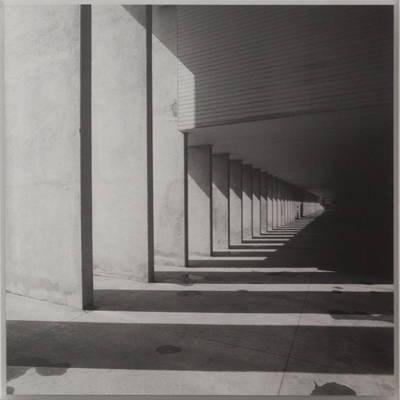

Installation view (Right Wall)

Takatani Shiro, frost frames / Europe 1987

Installation view (Left Wall)

Takatani Shiro, frost frames / Europe 1987

Installation view (Between Front Wall and Right Wall)

Takatani Shiro, mirror type k2

To put it plainly, a photographic way of seeing is characterized by the following: 1) It is a way of seeing based on “images” and presupposes a distance between viewer and subject (an image cannot be perceived if the lens is too close). 2) The fundamental units are surfaces (layers). 3) The image is seen from the viewpoint of no-one in particular, and the viewer’s eye can be substituted for this viewpoint. 4) The overlapping of “someone” “seeing” an image that “no-one in particular” “saw” gives rise to the separation and duplication of reality and consciousness. “Seeing” involves seeing the past in the present, the potential in the present, and the other in the self.

frost frames / Europe 1987 is a group of works in which scenes of Europe “as it used to be” photographed in such a way that the perspectival composition is accentuated have been placed inside square frames (= specimen cases) and put at a distance behind frosted acrylic (reminiscent of the ground glass in a large-format camera). The photographic way of seeing (1 and 2 above) is sealed in a casket and consigned to the nostalgic past.

Takatani Shiro, frost frame / Europe 1987 / pilotis 3

2013 / Giclee print, frost acrylic frame / 91.2 x 91.2 cm (36” x 36”)

mirror type k2, which occupies a bridge-like position between “photography” and “scanning,” is a simple and humorous device that modifies the photographic way of seeing (3 and 4 above; time difference and duplication). It is a mirror that enables the viewer to see in real time their own face as it is appears (as opposed to appeared) in a photograph. The non-reverse image of the viewer’s face, which others are used to seeing and shocking to the viewer alone, only appears when the viewer places their face directly in front of it. The only person able to see the scene directly in front of a mirror without being reflected in it has been “no-one in particular.” The viewer peers into the device as if they were that person, whereupon their self as seen through the eyes of the other person stares back.

Takatani Shiro, mirror type k2

2013 / knife-edge right angle prism with optical glass

14 x 28 x 20(h) cm (5_1/2″ x 11″ x 7_3/4″)

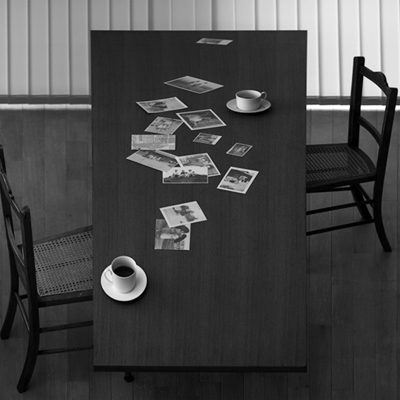

In Topograph, early 20th-century collage is recreated using a line scan camera, which is completely different in principle to collage, and the results placed in square frames as fake specimens, as it were. As the name suggests, a line scan camera scans the subject in lines, each with a width of one pixel. These lines (1D) are then joined together to produce an image (2D). The shocking thing about these works is that they are not collages of layers with different perspectives, but straight photographs. In other words, line scan cameras “see” the world with no notion of perspective to begin with!

Takatani Shiro, Topograph / La chambre claire 3

2013 / Giclee print, mounted on Alpolic

100 x 100 cm (39_1/4” x 39_1/4”)

Toposcan also references the problems of early Modernist painting – the dismantling and reconstruction of landscapes, Cezanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire, Post-Impressionism – although here the landscape is a symbol of European/Mediterranean civilization in the form of Paul Valéry’s “Le cimetière marin” (The Graveyard by the Sea). Scanned in panorama mode, this landscape repeats from the left hand edge and right hand edge of the screen in turn the transition ultrahigh speed (the screen image resolves into countless darting color lines) → normal speed (video) → stationary (photograph) → high-speed color lines again. This is not a moving image in appearance only created by joining together still frames, but a true moving image whose substrate* consists entirely of the high-speed movement of colorful lines. As the speed changes, this movement appears to the human eye as either “video” or a “photograph.”

Takatani Shiro, Toposcan

2014 / video installation / HD video, computer programing, plasma display

Scanning does not share the four characteristics outlined above. In principle, it is not seeing based on “images.” At the very least, one could hardly say that for humans a single line of pixels equates to an image. This is not spatial imaging, but the reception of subject information over a distance (a “sensor” feeling all over the subject with lines and dots). Similarly, the units for these images are not layers, but lines (or dots). The images are the result of combining the scanned line segments, and not images that “no-one in particular” “saw.” Accordingly, neither substitution nor duplication are possible, and the potential level (outside, other) also disappears.

In fact, digital technology is monistic. Surfaces are created from lines, and the movement and stillness of surfaces are created from the movement of lines. In other words, 1D and 2D, the points and lines of time, still images and moving images, death and life, and the other and the self are all continuous. This continuity, however, is not a nirvana-like dissolution, but an endless separation (the impossibility of differentiation). Is it actually possible for there to arise from art based on the kind of continuous seeing represented by scanning at resolutions with pixels becoming infinitely finer the kind of qualitative disconnection brought about by the disruptive seeing of photography, and if so, what kind of disconnection might this be?

This exhibition, which presents works that mourn for the otherness that arose from photography while referencing the two-dimensional expression of the early 20th century, also serves as a preparation for the unknown otherness that will no doubt arise from the digital technology of today. As artists who have a similar awareness of the issues involved here one could mention Thomas Ruff and Matsue Taiji, although given that digital technology renders continuous (as opposed to connected) not only moving images and still images but also sound (audio) and light (image), “disconnection” will probably appear first in the expression of multimedia artists like Takatani Shiro.

Shimizu Minoru

Art critic. Author of Hibi kore shashin (Everyday this photography) and Pururamon – tansu ni shite fukusu no sonzai (Pluramonity – on the existence of plurality in the mono), among others. Has also contributed texts to English-language exhibition catalogues and monographs for artists including Daido Moriyama, Hiroshi Sugimoto and Wolfgang Tillmans.

Takatani Shiro: Topograph/ frost frame Europe 1987 was on display at Kodama Gallery, Kyoto from 29 April to 14 June, 2014.

Courtesy of Kodama Gallery

—

*Incidentally, while simpler than Toposcan, Thomas Ruff’s Substrat series, which takes random images from the Internet and reduces them all to undulations of color, is based on the same concept.

Thomas Ruff Substrat 22-I (2003)

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

(Publication: 23 July 2014)