Odani Motohiko: Terminal Moment

by Hirayoshi Yukihiro

2014.12.08

Hirayoshi Yukihiro

To mark 400 years since founding of the Rinpa school of painting, the Kyoto Art Center staged the Odani Motohiko exhibition Terminal Moment. It was actually I who selected Odani for this project, having been privileged for a number of years now to be a member of the KAC executive committee. Setting aside the question of why Odani for Rinpa, as that question is also connected to the review below, I can say that for the KAC, which primarily supports emerging artists, to attract someone like Odani, who has successfully staged a major solo exhibition at the Mori Art Museum, was somewhat of a coup. Born and raised not far from the KAC, for his part Odani very much regretted not being able to take that solo exhibition launched at the Mori Art Museum back to his home turf. Since moving away from Kyoto on leaving high school, Odani has in fact never presented any of his work in exhibition format there. Moreover, the work exhibited by Odani in Skin of/in Contemporary Art organized by me at the National Museum of Art, Osaka may have been highly meaningful as a sculpture, but had limitations in terms of getting to the nub of his creative practice, which demonstrates its character best across a diverse range of media. In that sense, the staging of Terminal Moment had an inevitability of sorts for both sides. In saying that I was organizer of the exhibition, all I actually did was obtain Odani’s consent to stage a solo show, leaving the content of the show entirely to the artist himself. Thus my relationship with the works on display was virtually the same as that of any other viewer.

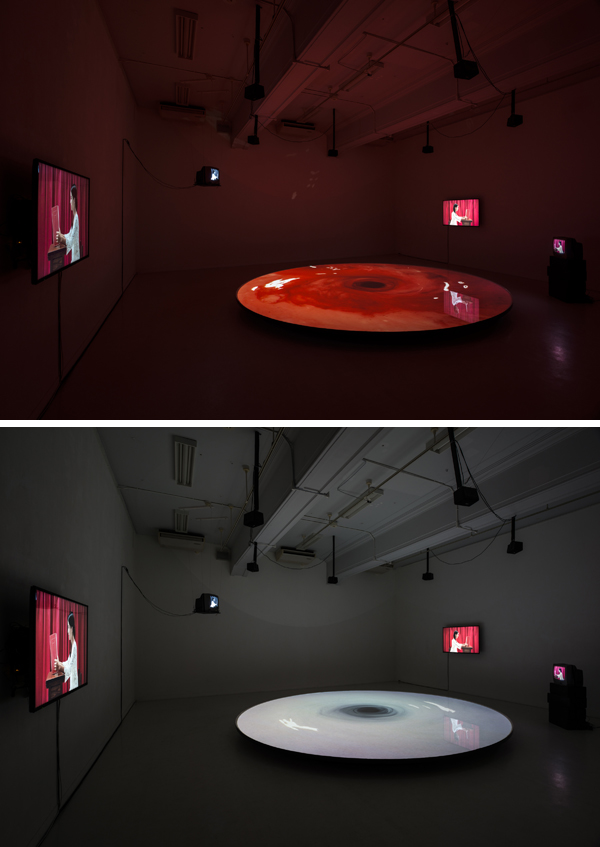

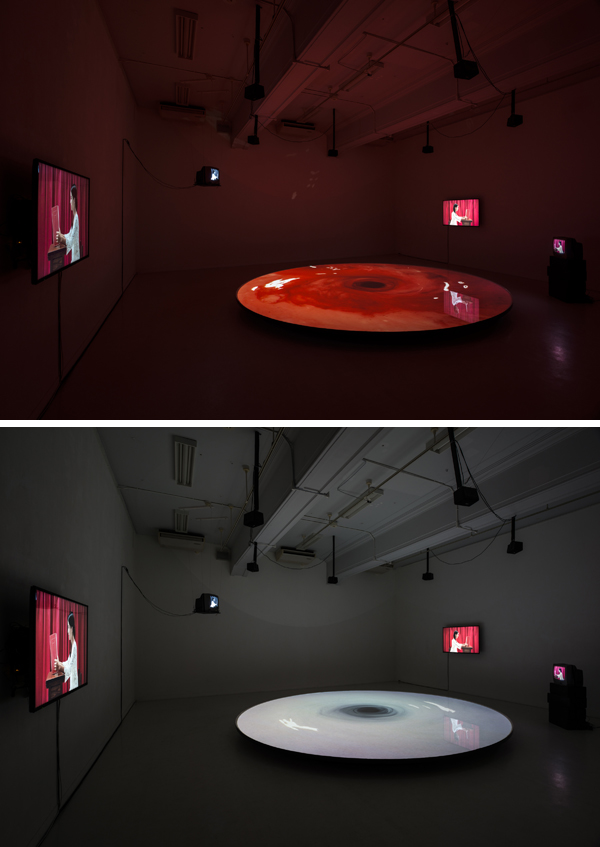

Three works made their appearance at the KAC. Terminal Documents (ver.2.0) installed in the north gallery is the latest version of a work added while the solo show was touring. Onto a giant round flower bowl installed close to the floor in the center of the room was projected a video of swirling bright red, viscous liquid. Meanwhile, on TV monitors set up around the bowl, a girl opens Jung’s Red Book, and actually reads aloud a passage from Hoffmann’s Sandman. As she reads, the liquid in the bowl suddenly turns white, then back to red. Terminal Documents (ver.1.1), composed of a monitor and collage, was installed in a small room next to the school’s water station, while the south gallery held new work Terminal Impact (featuring Mari Katayama “tools”). In video footage projected on three giant screens, a girl with two prosthetic legs is shown repeatedly going up and down stairs, sitting on a chair to perform tasks and so on. Around her are kuroko (traditional kabuki stagehands), who scurry about assisting her actions, moving surrounding machinery etc. Attached to the machines are severed feet molded from real feet, which the kuroko operate to move up and down, or rotate.

Odani’s works are formed by the multilayered intertwining of multiple meanings, so delve into their details and the possibilities are endless. And with regard to one of those important layers of meaning – the possibility/impossibility of creative practice in Japan since the Tohoku earthquake of March 2011 – it would be impossible not to reprise the subtle analysis of Sawaragi Noi in a dialogue with Odani held at the KAC on November 22. So here I shall instead consider the juxtapositional structure of the works installed in the two galleries, because I believe this juxtapositional structure reveals the basis of Odani’s thoughts on his relationship to sculpture.

The juxtaposition of the two works confronting each other across the empty sports ground played out on a number of levels. The red and yellow suffusing the spaces, the condensing toward the center of the vortex and the diffusion that unfolds with the videos on the three screens slightly out of sync (although ultimately they do become synchronized after a fashion), the torus and straight line patterns that segment the works, the reading voices and mechanical noise…. These contrasts supplied as visual and aural effects probably ought to be seen as amplifying the bipolar structure of the works’ realm, which unfolds around loss and compensation. The red of Terminal Documents is said to be the color people see in the instant they lose their sight, and the white the first color they sense on its return. Meanwhile there is probably no need to explain that Terminal Impact deals with loss and compensation. The title of this work refers to the impact on the kneecap produced at the point of contact with an artificial leg during walking. While Terminal Documents spans from the emergence of loss to the moment immediately before recovery, in contrast, in Terminal Impact it is the world after the compensation that unfolds. The realm of this loss and compensation of body parts has been a consistent theme for Odani since his early work Phantom Limb (referring to the compensation by electrical impulses for the loss of an extremity and the sensation of that body part), and as a structure has not only been concerned with questions of the human body, but overlaps with questions surrounding sculpture in Japan today.

The beauty of absence in sculpture is none other than the loss of body parts. A sculpture may be a perfect copy, but it is never more than fundamentally deficient to start with, and this lack leads the imagination to compensate. Yet at the same time, that compensation by no means gives a picture of the complete form. This relationship between loss and compensation in sculpture overlaps the more tangible problem of modern Japanese sculpture. Sculpture imported as a concept devoid of reality continues to produce works designed to make up for that lack, but the results are invariably odd and incapable of manifesting as a complete “sculpture.”

It’s not that Odani rejects Japanese sculpture. On the contrary, one could say he even attempts to draw out that oddness: because if sculpture is originally the deviation between loss and compensation, it is the very deviation between the concept of sculpture as phantom that has lost reality, and actual work as compensation, that is sculpture itself. Odani can only find reality in sculpture by confronting the definitive misalignment of loss and compensation, and taking on board as his own creative practice the terminal impact (final impact/of the terminal) born from the misalignment of compensation.

There is probably no longer any need to discuss the connection between Odani and Rinpa. Rinpa was not a school of painting arising from a teacher/pupil relationship, but a relationship brought about by a compensating for lost style, based on the individual interests of painters of different eras, locations and social status. What’s more, the “Rinpa” framework is one that emerged in the modern period, and could also be described as the concept of a phantom with no real form. In that sense, Odani, who is earnestly addressing the deviation between this concept as phantom and compensatory acts, is the only artist who can be connected to Rinpa in a contemporary form.

Hirayoshi Yukihiro

Associate Professor – Kyoto Institute of Technology Museum and Archives

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

Odani Motohiko: Terminal Moment was on display at Kyoto Art Center Gallery South & North, from 11 November to 14 December, 2014.

To mark 400 years since founding of the Rinpa school of painting, the Kyoto Art Center staged the Odani Motohiko exhibition Terminal Moment. It was actually I who selected Odani for this project, having been privileged for a number of years now to be a member of the KAC executive committee. Setting aside the question of why Odani for Rinpa, as that question is also connected to the review below, I can say that for the KAC, which primarily supports emerging artists, to attract someone like Odani, who has successfully staged a major solo exhibition at the Mori Art Museum, was somewhat of a coup. Born and raised not far from the KAC, for his part Odani very much regretted not being able to take that solo exhibition launched at the Mori Art Museum back to his home turf. Since moving away from Kyoto on leaving high school, Odani has in fact never presented any of his work in exhibition format there. Moreover, the work exhibited by Odani in Skin of/in Contemporary Art organized by me at the National Museum of Art, Osaka may have been highly meaningful as a sculpture, but had limitations in terms of getting to the nub of his creative practice, which demonstrates its character best across a diverse range of media. In that sense, the staging of Terminal Moment had an inevitability of sorts for both sides. In saying that I was organizer of the exhibition, all I actually did was obtain Odani’s consent to stage a solo show, leaving the content of the show entirely to the artist himself. Thus my relationship with the works on display was virtually the same as that of any other viewer.

Three works made their appearance at the KAC. Terminal Documents (ver.2.0) installed in the north gallery is the latest version of a work added while the solo show was touring. Onto a giant round flower bowl installed close to the floor in the center of the room was projected a video of swirling bright red, viscous liquid. Meanwhile, on TV monitors set up around the bowl, a girl opens Jung’s Red Book, and actually reads aloud a passage from Hoffmann’s Sandman. As she reads, the liquid in the bowl suddenly turns white, then back to red. Terminal Documents (ver.1.1), composed of a monitor and collage, was installed in a small room next to the school’s water station, while the south gallery held new work Terminal Impact (featuring Mari Katayama “tools”). In video footage projected on three giant screens, a girl with two prosthetic legs is shown repeatedly going up and down stairs, sitting on a chair to perform tasks and so on. Around her are kuroko (traditional kabuki stagehands), who scurry about assisting her actions, moving surrounding machinery etc. Attached to the machines are severed feet molded from real feet, which the kuroko operate to move up and down, or rotate.

Odani Motohiko, Terminal Documents (ver2.0), 2011 / Sound: Takashima Kei

Kyoto Art Center, Photo by Omote Nobutada

Odani Motohiko, Terminal Documents (ver1.1), 2014 / Sound: Takashima Kei

Kyoto Art Center, Photo by Omote Nobutada

Odani Motohiko, Terminal Impact (featuring Mari Katayama”tools”) , 2014 / Sound: Nishihara Nao

Kyoto Art Center, Photo by Omote Nobutada

Odani’s works are formed by the multilayered intertwining of multiple meanings, so delve into their details and the possibilities are endless. And with regard to one of those important layers of meaning – the possibility/impossibility of creative practice in Japan since the Tohoku earthquake of March 2011 – it would be impossible not to reprise the subtle analysis of Sawaragi Noi in a dialogue with Odani held at the KAC on November 22. So here I shall instead consider the juxtapositional structure of the works installed in the two galleries, because I believe this juxtapositional structure reveals the basis of Odani’s thoughts on his relationship to sculpture.

The juxtaposition of the two works confronting each other across the empty sports ground played out on a number of levels. The red and yellow suffusing the spaces, the condensing toward the center of the vortex and the diffusion that unfolds with the videos on the three screens slightly out of sync (although ultimately they do become synchronized after a fashion), the torus and straight line patterns that segment the works, the reading voices and mechanical noise…. These contrasts supplied as visual and aural effects probably ought to be seen as amplifying the bipolar structure of the works’ realm, which unfolds around loss and compensation. The red of Terminal Documents is said to be the color people see in the instant they lose their sight, and the white the first color they sense on its return. Meanwhile there is probably no need to explain that Terminal Impact deals with loss and compensation. The title of this work refers to the impact on the kneecap produced at the point of contact with an artificial leg during walking. While Terminal Documents spans from the emergence of loss to the moment immediately before recovery, in contrast, in Terminal Impact it is the world after the compensation that unfolds. The realm of this loss and compensation of body parts has been a consistent theme for Odani since his early work Phantom Limb (referring to the compensation by electrical impulses for the loss of an extremity and the sensation of that body part), and as a structure has not only been concerned with questions of the human body, but overlaps with questions surrounding sculpture in Japan today.

The beauty of absence in sculpture is none other than the loss of body parts. A sculpture may be a perfect copy, but it is never more than fundamentally deficient to start with, and this lack leads the imagination to compensate. Yet at the same time, that compensation by no means gives a picture of the complete form. This relationship between loss and compensation in sculpture overlaps the more tangible problem of modern Japanese sculpture. Sculpture imported as a concept devoid of reality continues to produce works designed to make up for that lack, but the results are invariably odd and incapable of manifesting as a complete “sculpture.”

It’s not that Odani rejects Japanese sculpture. On the contrary, one could say he even attempts to draw out that oddness: because if sculpture is originally the deviation between loss and compensation, it is the very deviation between the concept of sculpture as phantom that has lost reality, and actual work as compensation, that is sculpture itself. Odani can only find reality in sculpture by confronting the definitive misalignment of loss and compensation, and taking on board as his own creative practice the terminal impact (final impact/of the terminal) born from the misalignment of compensation.

There is probably no longer any need to discuss the connection between Odani and Rinpa. Rinpa was not a school of painting arising from a teacher/pupil relationship, but a relationship brought about by a compensating for lost style, based on the individual interests of painters of different eras, locations and social status. What’s more, the “Rinpa” framework is one that emerged in the modern period, and could also be described as the concept of a phantom with no real form. In that sense, Odani, who is earnestly addressing the deviation between this concept as phantom and compensatory acts, is the only artist who can be connected to Rinpa in a contemporary form.

Hirayoshi Yukihiro

Associate Professor – Kyoto Institute of Technology Museum and Archives

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

(Publication: 26 December 2014)

—Odani Motohiko: Terminal Moment was on display at Kyoto Art Center Gallery South & North, from 11 November to 14 December, 2014.