Dojima River Biennale 2015 Take Me To The River

by Ishitani Haruhiro

In the summer of 2015, Osaka is cool. The National Museum of Art, Osaka is offering “Time of others,” an exhibition of works reflecting on multiple histories, carefully chosen by four curators from Asia and Oceania; and a show devoted entirely to the oeuvre of Wolfgang Tillmans, laid out perfectly by the man himself – one of the world’s top contemporary photographers – during a two-week stay in Japan. Across the river, the cool factor is compounded by an exhibition at the Dojima River Forum offering an overview of the latest currents in top-quality, edgy contemporary art.

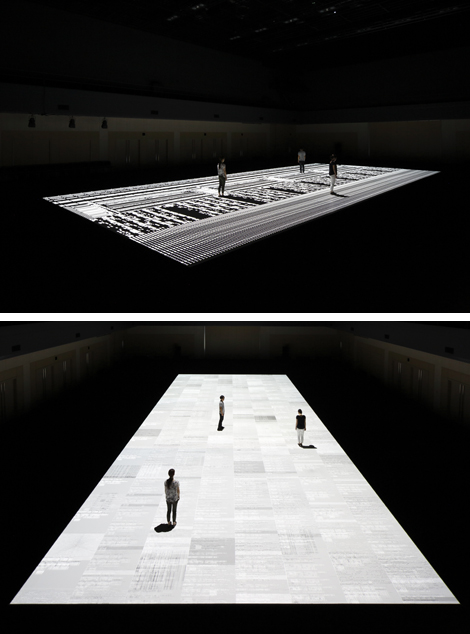

Beginning on the ground floor of the Dojima River Forum’s main hall, we find a gigantic work by sound artist Ikeda Ryoji. Aural stimulation in the form of shortwave sounds, pulsing and thumping bass accompanies lines of digital data racing across a screen extending across the floor. Visitors can stand on a structure similar to a theater stage to experience the light and sound, and the work and visitors as actors can also be viewed from the floor above. Ikeda Ryoji’s largest-ever installation in Kansai, it is worth dropping by the Dojima River Biennale just to experience it.

Ikeda Ryoji, deta.tecture |3 SXGA + version|, 2015, Courtesy: the artists

Installation view at Dojima River Biennale 2015 (Dojima River Forum)

Photo: Kioku Keizo, courtesy Dojima River Forum

The theme for this Biennale is “Take Me To The River,” and making the connection between this theme and Ikeda Ryoji’s installation, visitors may find the data flowing wave-like through the elongated space also brings to mind a pool or jacuzzi, sending a pleasant vibe through the body. In light of Ikeda’s previous, more understated approach of stimulating listeners with high-pitched or sudden noises, it was surprising to find that this time he has produced an installation with rhythm honed to a predictable range, refined to a level even a child could enjoy. One can easily imagine children happily surrendering to the sound and light, and having a blast. If I may say so, this is fun of a sort akin to that offered by the complex recreational facilities of artifical flowing water at places like Hirakata Park and Toshimaen. The theme for this Dojima River Biennale may well mean jumping into an imaginary river of digital data in a dark, air-conditioned room, to cool down in an intellectual manner, as opposed to spending the stifling summer knocked about by the hordes in a real pool.

Dojima is inextricably bound to its history as the site of the world’s first financial exchange, established through waterborne transport of rice during the Edo period. Capitalizing on the vertical structure of the buildings of the Dojima River Forum, a joint industrial and educational complex housing retail stores, offices and educational institutions, the intertwining of liquefying capital, information and nature in the exhibition rooms, dominated by Ikeda’s installation reminiscent of a data reservoir, unfolds in multiple layers. To put it simply, the passages and nearby exhibition rooms on the first and second floors point to the geopolitical expansion of modern globalization, while the underground carpark is the substructure providing the foundations of the world economy, and the exhibition room on the fourth floor with views out onto the forest of high-rises the superstructure of morals, art and so on. Based on this layered structure, issues in modern society surrounding history, ecology, food, education and emotional labor are arranged so as to resonate through images of water and fluidity. The Biennale is also notable for its concentrated retrospection on the work of international artists closely linked to the Japan of the 1980s onward.

View from the fourth floor of Dojima River Forum

Photo: Ishitani Haruhiro

The Play, 1E: PLAY HAVE A HOUSE, 2015 / video 1972, courtesy the artists

Installation view at Dojima River Biennale 2015 (Dojima River Forum)

Photo: Kioku Keizo, courtesy Dojima River Forum

Sasamoto Aki, Talking in Circles in Talking, 2015, Courtesy Take Ninagawa, Tokyo

Installation view at Dojima River Biennale 2015 (Dojima River Forum)

Photo: Kioku Keizo, courtesy Dojima River Forum

At this point, allow me to describe in some detail two works serving as incisive portrayals of the substructure and superstructure of today’s culture industry. Hito Steyerl’s Liquidity Inc. installed in the basement and lasting about 30 minutes, makes the fluidity of water a metaphor for modern society, while highlighting the strength of will exhibited by a mixed martial arts fighter who survives by riding the highs and lows of uncertain times in the manner of a surfer. Bruce Lee’s words, “Empty your mind. Be formless, shapeless like water,” are quoted repeatedly, as an MMA fight shows on the screen. In brief, the fighter is one of the children sent to the West Coast of the US for adoption after the Vietnam War. He achieves success working in an internet-related company, but is laid off in the economic collapse accompanying the demise of Lehman Brothers and ensuing financial crisis, and becomes a fighter. Thus the vicissitudes of one refugee’s life overlap with the paths taken by politics and economics in the last quarter of a century. War and terrorism are also in sync with the flow of money. As weather forecaster for an underground world, a masked man predicts the movement of air currents and tides, and the status of various conflicts from the South China Sea to the Pacific. The underground venue, a synthesis of boxing ring and private theater, inspires visitors with a fighting spirit that is the antithesis of comfort.

Hito Steyerl, Liquidity Inc., 2014

Courtesy the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York

Installation view at Dojima River Biennale 2015 (Dojima River Forum)

Photo: Kioku Keizo, courtesy Dojima River Forum

Vermeir & Heiremans’ 1-hour video work Masquerade on the top floor is a lecture performance video in which experts discuss the value of art as a special commodity. The democratization of the financial markets that started with 1980s neoliberalism made the language of politics subordinate to economics, engendering an unprecedented chasm between rich and poor that left 1 percent of the world’s population wealthy, and 99 percent in poverty. The nihilistic view would probably be that the art market is no more than a monopolistic market aimed at this wealthy 1 percent. By concocting the imaginary concept of the Art House Index (AHI) however, and rolling out multiple artworks solely in their own studio in Belgium, Vermeir & Heiremans et al delve into the paradoxical true nature of art and business. The first half of this thought experiment sets out a mechanism by which a proportion of monopolistic speculators and members of the elite manipulate the price of art and the market with ease, and the second half explains theoretically how the more viewers possessing diverse tastes and desires participate in the art world, the more unstable the very value of this index will become. That is to say, unlike the fake free competition principle of the financial markets, the true object of the democratization of art is to bring about a disturbance in the market’s value structure, making it crash and avoiding the manipulations of investors. But this educational video has yet another dimension: the people giving the presentations in it are curators and academics actually involved in the art sector, appearing as parodies of themselves. The magazine published to coincide with this exhibition contains texts full of academic notations and interviews conducted by the Biennale curator, and one can identify the names and faces of industry individuals cast in the video. Thus the title of Masquerade. So here we have a highly specialized game, an art world version of the film Ocean’s Eleven, so to speak. The incorporation of the history and site of Osaka’s Dojima in one location of ongoing attempts to survive this paradox is a welcome development.

Vermeir & Heiremans, Masquerade, 2015, Courtesy the artists

Installation view at Dojima River Biennale 2015 (Dojima River Forum)

Photo: Kioku Keizo, courtesy Dojima River Forum

Vermeir & Heiremans, In-Residence Magazine #02, 2015, Courtesy the artists

magazine, limited edition of 750 (detail) / Photo: Ishitani Haruhiro

A river is nature and simultaneously culture, and the very current incorporating multiple unique occurrences and objects into the distribution network of intangible global capitalism. To quote British sociologist Zygmunt Bauman, our global culture since the 1990s could be described as “liquid modernity.” This year’s Dojima River Biennale, at the hands of UK-based Tom Trevor offers a superb, multilayered view of the state of globalization right now, by connecting the simple metaphor of the river, and a well-thought-out selection of works.

Ishitani Haruhiro Art historian and art mediator. Currently doing Postdoctral resercher at the Konan University Institute of Human Sciences. Lecturer at Kyoto University of Art and Design, among other institutions.

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

(Publication: 17 September 2015)

Dojima River Biennale 2015 Take Me To The River

24 July – 30 August, 2015 / Dojima River Forum

Ryoji Ikeda, data.tecture [3SXGA+ version], audiovisual installation, 2015, © Ryoji Ikeda

concept, composition: Ryoji Ikeda computer re-programming: Tomonaga Tokuyama, Norimichi Hirakawa original computer programming: Shohei Matsukawa, Norimichi Hirakawa, Tomonaga Tokuyama