Jump over the line: On Furuhashi Teiji’s eternal LOVERS

by Ishitani Haruhiro

2016.07.10

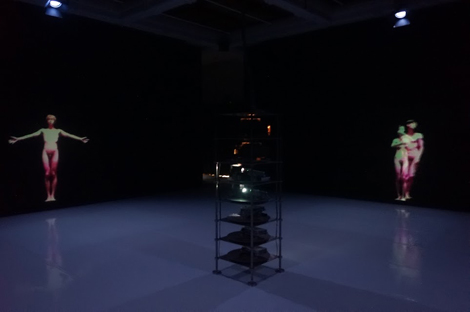

Furuhashi Teiji’s LOVERS –Installation, Kyoto Art Center AuditoriumPhoto: Ishitani Haruhiro

Ishitani Haruhiro

From July 9, 2016 Furuhashi Teiji’s LOVERS will be presented in Kyoto for the first time in eleven years. What distinguishes this presentation, in the hall on the second floor of the Kyoto Art Center, is that the version shown will be that restored last year with help from the Kyoto City University of Arts Archival Research Center and Dumb Type Office, supported by Media Arts at the Agency for Cultural Affairs. Media arts have a rich history in Japan, but it would be fair to say that restoration and conservation efforts by institutions such as museums and media centers have hitherto been inadequate, nor have the facilities and staff to carry out such work been put in place. This restoration attempt aims to be a test case in rectifying this state of affairs.

The LOVERS restored here is the second edition, produced by Dumb Type member Takatani Shiro to coincide with the opening of the Sendai Mediatheque in 2001. Minor readjustments were made to coincide with the unearthing of material shown in 1994. Every effort has been made to stay as close to the original as possible, for the benefit of future generations. The first version was added to the collection of New York’s MoMA in 1998, and will also be unveiled to the public, following restoration, from July 30, 2016. For the restoration of the second version carried out in Kyoto from 2015, material was found that showed the initial display to be 11m square, and one highlight this time is the recreation of the work using the dimensions of this original space. Conservation and restoration work also involved the building by Furudate Ken, Shiraki Ryo and others of a simulator to recreate the movements of the images in 3D. The Archival Research Center, which organized the project, will display associated resources in an adjacent conference room (see http://www.kcua.ac.jp/arc/lovers/ for the report).

Furuhashi Teiji’s LOVERS–Archive documents, Kyoto Art Center LoungePhoto: Ishitani Haruhiro

As well as enjoying a trip down memory lane, visitors who have encountered LOVERS in the past will doubtless find their thoughts turning to events of the last two decades or more. I must have seen LOVERS before, but am unsure where and when. Yet what I do definitely remember is a sense of nudes projected life-size onto a wall, suddenly appearing then disappearing in the gloom. Hopefully a whole new audience will now have the opportunity to discover the work, and feel its power for themselves.

Furuhashi Teiji’s LOVERS –Installation, Kyoto Art Center AuditoriumPhoto: Ishitani Haruhiro

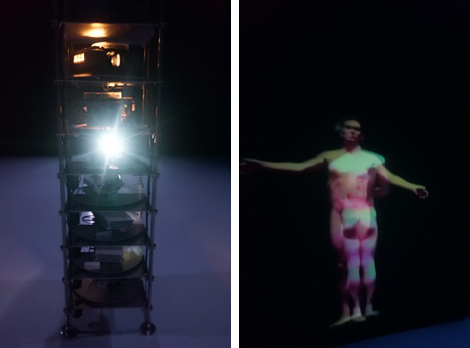

Dumb Type’s practice has consistently drawn our attention to the possibilities of art in response to technological change. The group also have a tendency to evoke the primitive origin myths of film, as seen for instance in the legend of Emperor Wu of Han – the silhouette of his loved one appearing on the screen – or Plato’s allegory of the cave, where we see the shadows of the actual objects as the world. Images composed of simple actions such as people walking, running, looking back, embracing, and the revolutions of the projectors projecting them are also linked to archaeological experiences of visual media such as the zoetrope, and Muybridge’s sequence photographs. The mid-1990s, when LOVERS was made, oddly enough coincided closely with the centenary of the birth of film. Amid recollections of the invention of cinema projection by the Lumiere brothers in the late 19th century, there was also a recurrence of pay-per-view content on personal media, for example with the video deck, whose origins extended back to the kinetoscope; and also the spread of computer games. At a fundamental level, these are linked to today’s culture of consuming visuals on our smartphones. Aptly, just as Jonathan Crary pointed out in Techniques of the Observer in 1992, while as phantasmagoria concealing their forms, visual devices for the consumption of images developed as technologies internalizing the panoptic gaze, and isolating/separating the individual from the group. Herein lies the significance of LOVERS being made using not the video monitors common at the time, but in a semi-theatrical installation format, with five rotating video projectors and slides installed on a 2m specially-constructed tower, projecting images on a black wall. The presence of this slightly overlarge human-size tower incorporates sculptural and architectural elements.

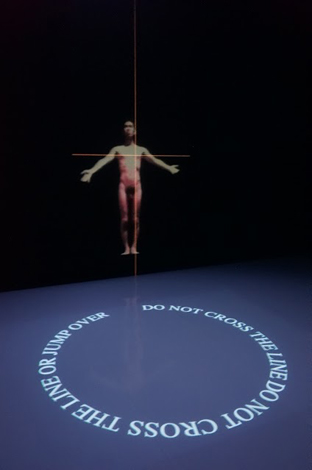

Furuhashi Teiji’s LOVERS –Installation, Kyoto Art Center AuditoriumPhoto: Ishitani Haruhiro

The central tower moves as it projects images of naked men and women onto the walls. The individual models sometimes appear to pass each other unconcernedly, or wind their arms around another but embrace only air, and at other times to look back and begin to run as if noticing someone has seen them, another person seemingly chasing them in response to the movement. Over the 15-minute duration of the piece, images of man and woman, woman and woman, man and man pass and overlap in polymorphic fashion. For the viewer, it is like looking into Charles Fourier’s “Le nouveau monde amoureux” (The New Amorous World) as if through Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon. The machine controlling this entire world of images is exposed for all to see, whirring away monotonously (in actual fact the control rack containing the DVD player etc. controlling the projector footage is also hidden behind the wall, via cabling that runs along the ceiling.) In the catalog, Furuhashi reveals the concept for the work to be “love under surveillance” and “love becoming surveillance.” In LOVERS the audience is also monitored, by a sensor. When the sensor on the ceiling is tripped, the viewer’s feet are surrounded by the text “DO NOT CROSS THE LINE OR JUMP OVER.” We are ordered to remain voyeurs or onlookers to naked images we will never be able to touch. If this is not the case, then try jumping over: fear and self-censorship form an invisible constraining limit. Sensor/censor: the interactive element of a work that responds to the viewer’s movements via a sensor is proof that this kind of monitoring mechanism is programmed into us.

Furuhashi Teiji’s LOVERS –Installation, Kyoto Art Center AuditoriumPhoto: Ishitani Haruhiro

It is surely this power to jump over a line or limit that Furuhashi assigned to the word “love.” In a fax sent from New York to Canon ArtLab curators Abe Kazunao and Shikata Yukiko, who assembled the work in 1994, Furuhashi explained that the words “DO NOT CROSS THE LINE” had their origins in the phrase written on barriers placed along the route of a gay pride parade (from Furuhashi Teiji, Memorandum, Little More, 2000). In his later years Furuhashi tackled the issue of the “still an unbridgeable gap in dimension” between the likes of technology and information capitalism, which attempt to render logical and systematic, and the way that individuals inevitably desire human encounters, and begin to love. Furuhashi explained it as follows.

“The seemingly slight yet enormous barrier lying between the simulated and real is the existence of this rigorous physical mechanism by which the irreversibility of the body puts a halt to cravings of the flesh. This subtle mechanism causes the ambitions of every next generation to crumble. The old-fashioned, meager word love is already all we have left to overcome this.” (p. 45)

Such ideas resonate even more keenly in today’s world of ubiquitous dating apps. Furuhashi, conscious of his physical deterioration due to HIV, considered the setting with the “creation closest to ‘love’” to be not the museum or gallery or theater, but the New York nightclub Sound Factory, where his friends gathered. He describes his experience there:

“Individuals different in myriad ways are liberated from both body and information, existing simultaneously and equally in space and time, sharing the eternity of sensation. The way in which the accumulated dissemination (expression) of each individual’s coincidental sensations construct each moment changes at unthinkable speed, thanks to the extreme environment created by sound and light media.” (p. 48)

In LOVERS, Furuhashi’s image walks slowly across the black wall, and just as it passes in front of the viewer, a sensor is activated, making him look back this way for a moment. Then just as Furuhashi seems about to embrace the viewer, he falls away, disappearing into the darkness. Was the world beyond the screen into which Furuhashi plunged a just place, liberated from body and information? Here, the Furuhashi whom we assumed lost appears once more, so it would be fair to say that it is not so much the aesthetics of disappearance that dominate as a transboundary quality, the way the artist moves to and fro over the line between here and there, like an acrobat.

More than twenty years on, in the world where we live only information capitalism crosses national borders, while violence and fear persist, and the barriers between us, both physical and psychological, grow ever higher. On June 12, just as I was rereading Furuhashi’s words, word of the tragedy in Orlando reached me. A memorial message for the victims, “Love will always win,” was all over social media, as was news of parades in various locations, and Furuhashi must be watching eternally as we try to jump over that line, under the banner of love.

Ishitani Haruhiro

Research fellow

Kyoto City University of Arts, Archival Research Center

For Furuhashi Teiji’s LOVERS –Installation, Archive documents, Night party, Symposium, Film screening 9th [sat.] – 24th [sun.] July 2016 Kyoto Art Center

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

(Publication of the English version: July 22, 2016)