A universal view of the world built upon human closeness: Does “little” mean “little”?

by Kataoka Mami

2013.08.05

Kataoka Mami

Avid collector of contemporary art Rudy Tseng took early retirement from his executive position at Walt Disney International Taiwan, and declared himself unemployed or alternatively, a full-time art collector. His involvement in and knowledge of the world of art is substantial. He visits artists’ studios, meeting with the artists in person, and through his art purchases, supports both artists and gallerists. For several years, coinciding with the Taipei art fair season, he has organized an exhibition in a designer furniture showroom in the city. Rudy gets things done in a seemingly effortless way, resolves situations quickly and pays attention to the small things. It is not difficult to see how he came to be in charge of such large business operations.

The theme of “Little Water,” the exhibition curated by Rudy, is “water,” a substance known to everyone on earth and a theme open to a multitude of interpretations. More than a few of the participating artists are counted as Rudy’s friends. The relationship between them is a close and personal one, built through his purchase of their art and his innate understanding of the way they think and of their value system. What kind of universality can be seen in a worldview built from such relationships? This concept of the micro-cosmos and the macro-cosmos becoming one is interesting indeed. During several email exchanges with Rudy in the early stages of planning of the exhibition, I was asked my opinion about the theme and suggested making a list, in actual terms, of the relationships that could be found within the work of the artists with whom he had already established close and trusting relationships and the one they had with him. The fact that the work Rudy had collected must surely be a reflection of his own value system and aesthetic eye meant that a foundation for planning the exhibition could possibly be found therein.

The theme he eventually chose, “Little Water,” was reflected in a highly interesting way – in the poetic abstraction that runs through the whole exhibition, the way in which the serene exhibition space and the lighting had been set up, and a consistent aesthetic approach in the art. It is a worldview built upon the intimacy of the limited space that was adapted with great elegance for the exhibition, incorporating to the fullest extent Rudy’s personal ideology and his attention to detail in the use of space. In writing commentary on the exhibition, it was difficult for me to be entirely objective or to consider the exhibition from a critical perspective, as I know Rudy and some of the participating artists and their works all too well, but even when that is removed from the equation, the work selected for the exhibition is not Rudy’s way of visualizing or spatializing his own thinking. Rather, the understanding that he himself has for the work as the person who planned the exhibition is reflected within the space as something more universal.

The “little” value system of “Little Water” is a counter theme to, for instance, the “Big Wave” theme of the First Yokohama Triennale and to “Abenomics,” the advocating of strategies for endless growth in a country undergoing a process of contraction. However, the “little water” Rudy talks about, although it involves the concept of physical size, is not the kind of smallness that is inferior to largeness.

On the contrary, it is the concept that, in the same way that the Ursa Major constellation in the night sky is projected onto the dry landscape garden in the Tofukuji Hojo garden designed be Shigemori Mirei, a “micro-cosmos garden” planted in a box is capable of symbolising the Chinese concept of sēn luó wàn xiàng, or the whole of creation. In Shinoda Taro’s GINGA, the concept runs through the idea of the ripple pattern caused by water droplets falling from the ceiling onto the black surface of water intermixed with India ink. The same universality can be seen in the work of Wolfgang Laib who, for his sculptures, uses materials that are “sources of life” or contain nutritional substances in a condensed form such as pollen, beeswax, rice, and milk. Milkstone (1975) is one of his first works, in which Laib, who initially studied medicine, through his contact with Indian philosophy, turned from the job of saving people’s lives towards becoming an artist who considers the origins of life, the same thing he wanted to do by becoming a doctor. Each day, fresh milk is poured onto a small rectangular piece of marble, testing the surface tension of the marble to its limits, and at the end of each day the process of wiping away the milk is repeated. Like the ritual of serving tea to guests in the intimate space of a tea house, Milkstone welcomes visitors at the entrance to the exhibition and makes us stop and wonder about the origins of life. It is not created from a permanent substance. Rather, like the river in which the same water will never flow twice, it is fluid and unfixed.

The ambiguous nature of water in Shakespeare’s Macbeth is also highly interesting. The title of the exhibition comes from the words uttered by Lady Macbeth to her husband who comes to her covered in blood after murdering King Duncan of Scotland, “A little water clears us of this deed.” However, the smell of blood on her hands causes Lady Macbeth to be gripped by an obsession and she gradually descends into madness. This causes us to think about the stupidity of human beings who have believed that we could treat the ocean badly with impunity (exemplified by, for example the still unresolved issues relating to treatment of polluted water at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant and the releasing of industrial wastewater into the rivers and the sea by Japanese companies during Japan’s era of high economic growth) and the ambiguity of the reality that we don’t know when the water will be completely clean again.

Tsai Charwei’s Lanyu relates how this self-indulgent reliance of human beings on water is not limited to specific localities. A “temporary” preservation facility for nuclear waste was built on an island inhabited by the indigenous people of Taiwan and the facility will continue to release polluted water on a permanent basis. The black-and-white photograph was taken on a moonlit night and Sanskrit characters (the Heart of Great Perfect Wisdom Sutra) were written by hand on top of the flowing water that is captured in the photo.

The exhibition with its grand theme of “water” will take the viewer’s thinking and consciousness to a new and higher level. Thinking built upon close relationships with the artists leads to a broader worldview. Rudy has apparently enjoyed the game of curatorial thinking and practice and seems keen to continue in the business of curating. The writer, however, would prefer to become a full-time collector … .

Kataoka Mami (Chief Curator, Mori Art Museum)

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

Avid collector of contemporary art Rudy Tseng took early retirement from his executive position at Walt Disney International Taiwan, and declared himself unemployed or alternatively, a full-time art collector. His involvement in and knowledge of the world of art is substantial. He visits artists’ studios, meeting with the artists in person, and through his art purchases, supports both artists and gallerists. For several years, coinciding with the Taipei art fair season, he has organized an exhibition in a designer furniture showroom in the city. Rudy gets things done in a seemingly effortless way, resolves situations quickly and pays attention to the small things. It is not difficult to see how he came to be in charge of such large business operations.

Photo by Kozo Takayama

The theme of “Little Water,” the exhibition curated by Rudy, is “water,” a substance known to everyone on earth and a theme open to a multitude of interpretations. More than a few of the participating artists are counted as Rudy’s friends. The relationship between them is a close and personal one, built through his purchase of their art and his innate understanding of the way they think and of their value system. What kind of universality can be seen in a worldview built from such relationships? This concept of the micro-cosmos and the macro-cosmos becoming one is interesting indeed. During several email exchanges with Rudy in the early stages of planning of the exhibition, I was asked my opinion about the theme and suggested making a list, in actual terms, of the relationships that could be found within the work of the artists with whom he had already established close and trusting relationships and the one they had with him. The fact that the work Rudy had collected must surely be a reflection of his own value system and aesthetic eye meant that a foundation for planning the exhibition could possibly be found therein.

Photo by Kozo Takayama

The theme he eventually chose, “Little Water,” was reflected in a highly interesting way – in the poetic abstraction that runs through the whole exhibition, the way in which the serene exhibition space and the lighting had been set up, and a consistent aesthetic approach in the art. It is a worldview built upon the intimacy of the limited space that was adapted with great elegance for the exhibition, incorporating to the fullest extent Rudy’s personal ideology and his attention to detail in the use of space. In writing commentary on the exhibition, it was difficult for me to be entirely objective or to consider the exhibition from a critical perspective, as I know Rudy and some of the participating artists and their works all too well, but even when that is removed from the equation, the work selected for the exhibition is not Rudy’s way of visualizing or spatializing his own thinking. Rather, the understanding that he himself has for the work as the person who planned the exhibition is reflected within the space as something more universal.

The “little” value system of “Little Water” is a counter theme to, for instance, the “Big Wave” theme of the First Yokohama Triennale and to “Abenomics,” the advocating of strategies for endless growth in a country undergoing a process of contraction. However, the “little water” Rudy talks about, although it involves the concept of physical size, is not the kind of smallness that is inferior to largeness.

Shinoda Taro GINGA

Photo by Kozo Takayama

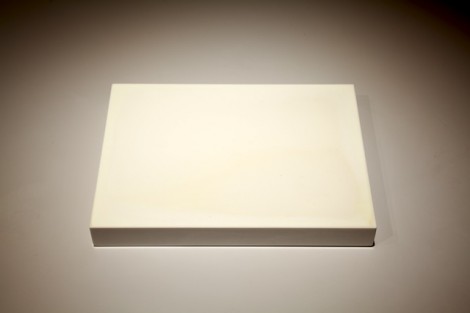

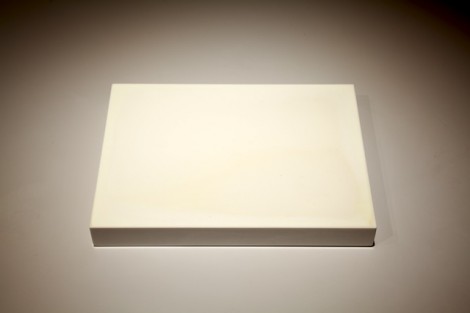

On the contrary, it is the concept that, in the same way that the Ursa Major constellation in the night sky is projected onto the dry landscape garden in the Tofukuji Hojo garden designed be Shigemori Mirei, a “micro-cosmos garden” planted in a box is capable of symbolising the Chinese concept of sēn luó wàn xiàng, or the whole of creation. In Shinoda Taro’s GINGA, the concept runs through the idea of the ripple pattern caused by water droplets falling from the ceiling onto the black surface of water intermixed with India ink. The same universality can be seen in the work of Wolfgang Laib who, for his sculptures, uses materials that are “sources of life” or contain nutritional substances in a condensed form such as pollen, beeswax, rice, and milk. Milkstone (1975) is one of his first works, in which Laib, who initially studied medicine, through his contact with Indian philosophy, turned from the job of saving people’s lives towards becoming an artist who considers the origins of life, the same thing he wanted to do by becoming a doctor. Each day, fresh milk is poured onto a small rectangular piece of marble, testing the surface tension of the marble to its limits, and at the end of each day the process of wiping away the milk is repeated. Like the ritual of serving tea to guests in the intimate space of a tea house, Milkstone welcomes visitors at the entrance to the exhibition and makes us stop and wonder about the origins of life. It is not created from a permanent substance. Rather, like the river in which the same water will never flow twice, it is fluid and unfixed.

Wolfgang Laib Milkstone

Photo by Kozo Takayama

The ambiguous nature of water in Shakespeare’s Macbeth is also highly interesting. The title of the exhibition comes from the words uttered by Lady Macbeth to her husband who comes to her covered in blood after murdering King Duncan of Scotland, “A little water clears us of this deed.” However, the smell of blood on her hands causes Lady Macbeth to be gripped by an obsession and she gradually descends into madness. This causes us to think about the stupidity of human beings who have believed that we could treat the ocean badly with impunity (exemplified by, for example the still unresolved issues relating to treatment of polluted water at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant and the releasing of industrial wastewater into the rivers and the sea by Japanese companies during Japan’s era of high economic growth) and the ambiguity of the reality that we don’t know when the water will be completely clean again.

Tsai Charwei Lanyu

Photo by Kozo Takayama

Tsai Charwei’s Lanyu relates how this self-indulgent reliance of human beings on water is not limited to specific localities. A “temporary” preservation facility for nuclear waste was built on an island inhabited by the indigenous people of Taiwan and the facility will continue to release polluted water on a permanent basis. The black-and-white photograph was taken on a moonlit night and Sanskrit characters (the Heart of Great Perfect Wisdom Sutra) were written by hand on top of the flowing water that is captured in the photo.

The exhibition with its grand theme of “water” will take the viewer’s thinking and consciousness to a new and higher level. Thinking built upon close relationships with the artists leads to a broader worldview. Rudy has apparently enjoyed the game of curatorial thinking and practice and seems keen to continue in the business of curating. The writer, however, would prefer to become a full-time collector … .

Rudy Tseng

Kataoka Mami (Chief Curator, Mori Art Museum)

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

(Publication: 16 August 2013)