A killer blow to Araki’s career?

by Iizawa Kotaro

A blog post titled Sono chishiki, honto ni tadashii desu ka (Is that understanding really correct?) by KaoRi, a former model for Araki Nobuyoshi, has recently ignited huge controversy.

https://note.mu/kaori_la_danse/n/nb0b7c2a59b65

In a very honest piece of writing, this woman who was ostensibly Araki’s “muse” gives a remarkably straightforward, disinterested account of how she was “continually treated like an object” with no contract and virtually no financial recompense, how images of her were reworked/retouched without consultation by numerous parties including Araki himself and various editors, and how no effort was made to address these issues despite a serious physical and mental toll on her that led to complete burnout. The post, which avoids simply criticizing and accusing Araki, instead asking that they both acknowledge the facts of the matter, concludes by expressing the desire for a “world that evolves alongside individuals’ respect for each other.”

When it comes to the particular issues between Araki and KaoRi, I have no intention of adding my two cents. However I have noticed that much of the response to KaoRi’s blog post has been highly emotive in nature and critical of Araki, without understanding the background to his photography, and believing this to be less than desirable, decided to set out my own view on the matter at this point in time.

What struck me most reading KaoRi’s piece, was how times have changed. As a photography critic, I first started to follow Araki Nobuyoshi and his work closely in the 1990s, but the way Araki and his models related to each other, and the zeitgeist itself, changed dramatically in the succeeding years.

In the 1990s, a lot of women approached Araki wanting to be photographed by him, clamoring to be his models, moreover nude models photographed in hard-core activities including bondage. Though KaoRi herself has not stated as such, if anyone reading her post imagines Araki has been forcing women to pose naked for his photos all these years, I can tell you unequivocally this is not the case. On the contrary, women hoping to become models actively wanted to be photographed by him.

Why was this? Well I suspect it was because the social climate surrounding these women was much tougher then than now. The constraints of family, school, and workplace were tighter, and hurdles to self-actualization many. For these women the decision to go naked was also the manifestation of a powerful desire to take control of their body and soul into their own hands. I recall a trend for “self nudes” at the time. Girls who could use a camera started to disrobe and take photos of themselves. But when this was tricky, for various reasons, some must have wanted to have pictures taken by someone else. Araki was for them, one of the most attractive “someones” for the job.

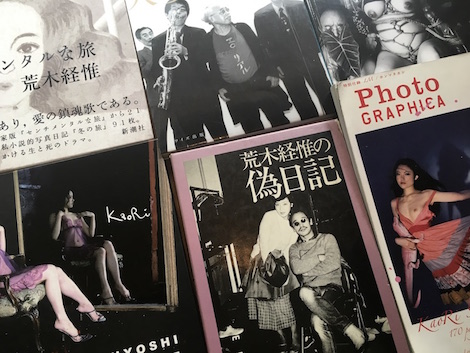

Why him? Doubtless several reasons. Obviously, the fact that his photos were so brilliant. These women instinctively sensed his ability to coax out their hidden erotic power. Also influential, no doubt, was his status as the creator of Senchimentaru na tabi—Fuyu no tabi (Sentimental journey—Winter) (1991). The photos Araki continued to take around the time of his beloved wife’s death played a major part in feeding the popular narrative of a photographer with a bad-boy reputation, who was actually a “kind” person. One imagines many of the women shared the desire to be watched over in the way that Yoko was.

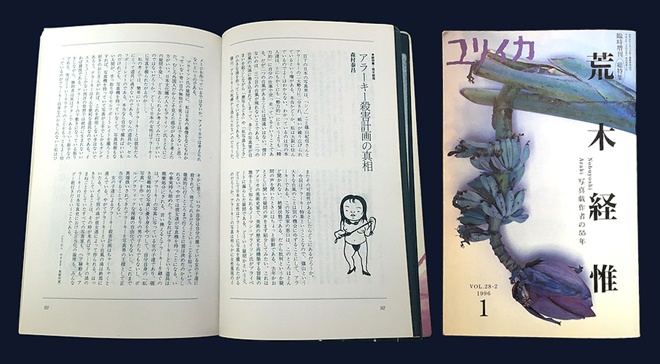

At the time, one artist did see right through what one might term the codependent relationship between Araki and his models. Reading back on this occasion through various writing on the photographer, I came upon a surprisingly prescient essay titled “The truth about the plot to kill Arākī” (Araki’s nickname, used throughout this text in reference to the photograph’s persona) penned by Morimura Yasumasa for a January 1996 special edition of Yuriika (Eureka): “Araki Nobuyoshi – 55 years of a popular photographer.” In it, Morimura writes:

To my mind, to the women, quite simply, Arākī is no more than a tool of sorts, a tool for self-portraiture. Really they should take their own portraits, but in the absence of a camera, or the requisite photography skills, who wanting a handy way to take a self-portrait is not going to make use of an old guy in possession of a camera, who takes good photos, and moreover is a bit of a ladies’ man? Arākī is this convenient tool… Actually I have a sneaking suspicion the man himself understands these machinations better than most. He may well know that eventually, he’ll be bumped off and discarded by the women he’s photographing, and have decided to just go all out and take this thing as far as he can, in the knowledge that one day, they will hold the camera. Actually, they’ve already started to do so. Once that occurs, Arākī, as their means to an end, will be cast aside.

A very accurate analysis, in my view. Araki was for these women a “convenient tool” for taking some undoubtedly splendid “self-portraits.”

For his part, Araki knew exactly how he wanted to photograph them: as “harlots.” Jokan-ji, Araki’s family temple, situated in front of his family home, is also known as a nagekomi-dera because the remains of prostitutes from the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters who died without family to claim them were nagekomareta (thrown or dumped) there. This historical fact was etched on Araki’s psyche. In addition, the image of the harlot or whore dominated male sexual fantasy from the prewar years through the postwar period. Think of Nakanishi Rei’s single Toki ni wa shofu no yo ni [Just sometimes, be like a woman of the night] (1978) and you get the idea: “Just sometimes, be a loose woman/like a woman of the night/Put on bright red lipstick/And black socks/Stand legs astride/And give me a wink.” Incidentally, Nakanishi Rei was born in 1938, making him a contemporary of Araki, born in 1940.

Araki endeavored to superimpose that image of the “harlot” on his models. And they in turn were still equipped with a kind of bodily memory that allowed them to cater to this desire. It used to be said of Japanese cinema that if you “make women play prostitutes, and men soldiers, they slip perfectly into the role.” The pathos of the prostitute and the soldier may be described as a vestige of an older, poorer Japan. Perhaps through the years of booming postwar economic growth, to the 1990s when the bubble burst, it just managed to hang in there, as an image still able to be shared by all.

But “times have changed.” As Morimura Yasumasa foresaw, the models now have cameras. Advances in digital technology and the advent of mobile phones with cameras mean there is no longer anyone without a camera or photography skills. Social media such as Instagram are overflowing with the output of these women’s self-actualization and self-expression. They no longer have any use for Araki as “a convenient tool.” Naturally, the image of the harlot has also lost its power to excite, and now seems simply anachronistic.

Another notable thing about the digital era is that electing to “go nude” is now a far riskier act than before. What ought to have been a one-off adventure, once spread all over the internet, brings unexpected trouble. Having weighed up the pleasure of stripping off, against the danger, they are now choosing to keep their clothes on.

By the 2000s, the number of women wanting to be models for Araki was slowly falling. Reading KaoRi’s piece, what surprised me a little was that she worked as Araki’s model from 2001 to 2016, a whole sixteen years. Previous models probably lasted two to three years at the most: that is how quickly a succession of models to Araki’s liking appeared. And on the women’s part too: once their desire for self-actualization had been satisfied, they made themselves scarce. That KaoRi remained Araki’s “muse” for that long is largely due, one strongly suspects, to a lack of replacements. And also, one might speculate, that now over seventy and not always in good health, Araki had fewer opportunities to dip in and out of Tokyo nightlife and form contacts with women.

Unfortunately, in those sixteen years, the rift between Araki and KaoRi, between photographer and model, grew too great to repair. Araki continued to project his obsession with the “harlot” on KaoRi, and KaoRi began to develop a powerful sense of dislike and discomfort at being made to move and behave according to Araki’s will, being “treated like an object.” If they had been able to sever their ties skillfully at that point, KaoRi would doubtless not have struggled so much, but it was not to be. One can only imagine with regard to this, that both had a powerful attachment to taking photographs, and being photographed.

I’d like to point out also that from 2000 onward, there was a change in the quality of Araki’s approach to his shishashin (I-photography). Shishashin is a style of photography developed in the 1970s by Araki and other photographers such as Fukase Masahisa, in which the subtleties of relationships with intimate others is related in detail, in the form of a photographic diary. As a style it subsequently gained a sizable following, coming to constitute a major current in Japanese photographic expression. What one ought to be aware of, however, is that Araki’s shishashin had a rather distinctive bias right from the beginning, in the form of an especially slender margin between reality and fiction. At any given time Araki would present a mixture of real, everyday occurrences, and fictitious, staged events. Borrowing from the title of his 1981 photobook, Nobuyoshi Araki – Pseudo-Diary / No Nise Nikki, these photos may be referred to as “pseudo (fake)-shishashin.”

Playing a vital role in construction of this “pseudo-shishashin” realm was the conversion of those appearing in that realm into “characters.” Araki had been engaged whole-heartedly in this since the days of Shashin Jidai magazine in the 1980s. Here we see his wife “Yoko” (Araki Yoko), the editor “Suee” (Suei Akira), models “Rena-chan,” “Sanzen’in Kyoko” and “IZUMI” (Suzuki Izumi), needless to say with “Arākī” the biggest character of all. For sure, this was a fake world. But Araki knew very well that the fake conversely has the power to draw out and illuminate the real.

In other words, in one respect Araki-style shishashin was a show with an all-star cast, performed by the Araki theater company, led by the character “Arākī.” To stage such a show demanded the ability to freely manipulate the performers-turned-characters and run perfectly a playhouse positioned in that margin between reality and fiction. In the 1990s the offerings of Araki’s troupe of actors became more refined, and capable of giving pleasure to many. By the 2000s though, Araki’s ability to identify the individual qualities of his performers and create new characters, was slowly starting to flag. Hardly surprising really: to sustain the Araki theater company and the character “Arākī” demands unbelievable reserves of energy.

Needless to say KaoRi was the star actress in the Araki troupe. However, around the time she made her appearance, the company’s offerings were already becoming stale, with much blatant repetition. It is around this time that the “harlot” imagery began to fall into the same particular pattern. In saying that, Araki’s shishashin still possessed much to fascinate. Looking at the series of photobooks containing that year’s shinikki (personal diaries), published by Wides Publishing, it is obvious that Araki’s skill at taking, selecting and arranging photographs was still unrivaled. Unfortunately however, it was probably already too difficult for Araki to keep giving KaoRi suitable roles to play.

Now as I wrote at the beginning, KaoRi’s comments were in my opinion exceedingly honest and decent. Hopefully, their widespread exposure will result in an improvement in the situation.

What I do fear now, however, is that KaoRi’s accusations will result in not just the photos of her, but all of Araki’s work being seen in a negative light. At the very least, it will no longer be possible to look at Araki’s nudes with the same degree of innocence as previously. Even so, I think it would be a dreadful shame to kill off “Arākī” completely. The images of nudes, bondage, and “harlots” are only one element of a “world of Araki Nobuyoshi” reminiscent of a large orchestra. Obviously they are a very important group of images, but the realm of Araki’s photography, swallowing up all of creation as it does, capturing life and death in a single sweeping vision, extends far beyond that.

I would even go so far as to say, let us not reject completely those very images of nudes, bondage and “harlots.” Not a few of the many nude photography shoots Araki has done to date have been truly soul-stirring occasions involving a clash between the photographer who wants to take the photo a certain way, and the ego of the model, who wants to be captured another way, with sparks flying as a result. If at all possible we must avoid a situation whereby these photos, including those of KaoRi, can no longer be displayed or published.

One cannot deny that Araki does display, in his speech and conduct, the danson-johi male chauvinism to which males of his generation are susceptible. One suspects however, that this is the flipside of a certain awe of women: a mixture of respect and fear. There is something about Araki’s approach to photography – shot through with a view of women that at times has inclined toward the overly macho – clasping tightly in its grip all the weirdness of human existence, that I must confess I find irresistible.

Thinking about it, before the 1980s, Araki was a minor presence known only to those in the know. From the ‘90s onward, in a remarkable reversal of fortune, a hitherto notorious reputation took a positive turn, earning Araki the status of an “authority” and “photographer for the people.” This state of affairs was in turn, perhaps extraordinary. In my view, it wouldn’t be a bad move for Araki to address the current unfavorable circumstances square on, and walk once more the royal road of a great minor artist. There are not that many photographers whose new work I am always keen to see, but Araki Nobuyoshi was one, and no doubt will continue to be.

Postscript

KaoRi has posted a new blog entry titled “The story from here.”

https://note.mu/kaori_la_danse/n/n87637ae05198

In it, she writes as follows:

My intention was simply to do whatever I can do now, in the context of respect for Araki-san’s wish to continue exhibiting and selling photographs of me, and am confident this is not in order to damage his reputation. Araki’s photos are not only photos of me, after all, and many are excellent pieces of work… Picasso, Rodin, Warhol are all artists who were embroiled in scandal, yet are still talked about today. My wish however, is for treating people as objects in the name of art to cease. Against such a background, if the photos continue to be displayed and sold, I imagine some kind of action will be necessary. Hopefully the photos, and any action taken, will give people a sense of this particular period in art history. So whether to remove works or not, is entirely up to art museums, and those involved in art.

I agree. Individuals should set or reset their own criteria for appraising Araki’s work, having first understood the entire backdrop to it. Personally, even if he is “embroiled in scandal,” my view is still that in the genre of photography, Araki Nobuyoshi is an artist of peerless talent.Iizawa Kotaro Photography critic. Born 1954 in Miyagi Prefecture. Graduated in 1977 from the Department of Photography, Nihon University College of Art, earning his PhD at the University of Tsukuba in 1984. Among his many books are Shashin bijutsukan e yōkoso [Welcome to the photography museum] (Tokyo: Kōdansha, 1996), Shi-shashinron [Theory of I-Photography] (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 2000), Dejigurafi: Dejitaru wa shashin o korosu ka? [Digital photography: Will digital kill photography?] (Tokyo: Chūōkōronsha, 2004), Zōho: Sengo shashin-shi nōto [Postwar photo-history notebook] (Tokyo: Iwanami Bunko, 2008), Afutāmasu ― shinsai-go no shashin [Aftermath: Photography after the great earthquake], co-authored with Hishida Yusuke (Tokyo: NTT Shuppan, 2011), Kīwādo de yomu gendai nihon shashin [Japanese photography read via keywords] (Tokyo: Fimartsha, 2017).

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

(Publication: 6 May 2018)