Cultural Currency 33

The Shadow of Fascism

By Shimizu Minoru

2025.03.08

At the end of February I visited Vienna to do research on the art scene there, but the thing that left the strongest impression on me was the evening I spent at the Wiener Musikverein. The program, performed by the Vienna Symphony Orchestra conducted by Patrick Hahn with Kirill Gerstein on piano and Cornelius Obonya narrating, consisted of Arnold Schoenberg’s “Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte,” op. 41b, version for string orchestra, piano and narrator; Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat Major, op. 73; and, after an intermission, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, op. 55 (“Eroica”), with Napoleon clearly standing front and center.

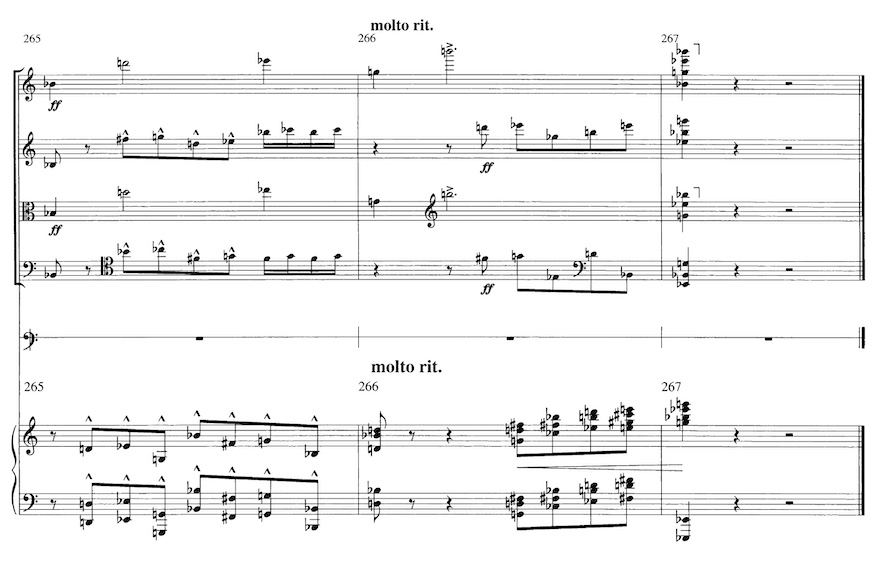

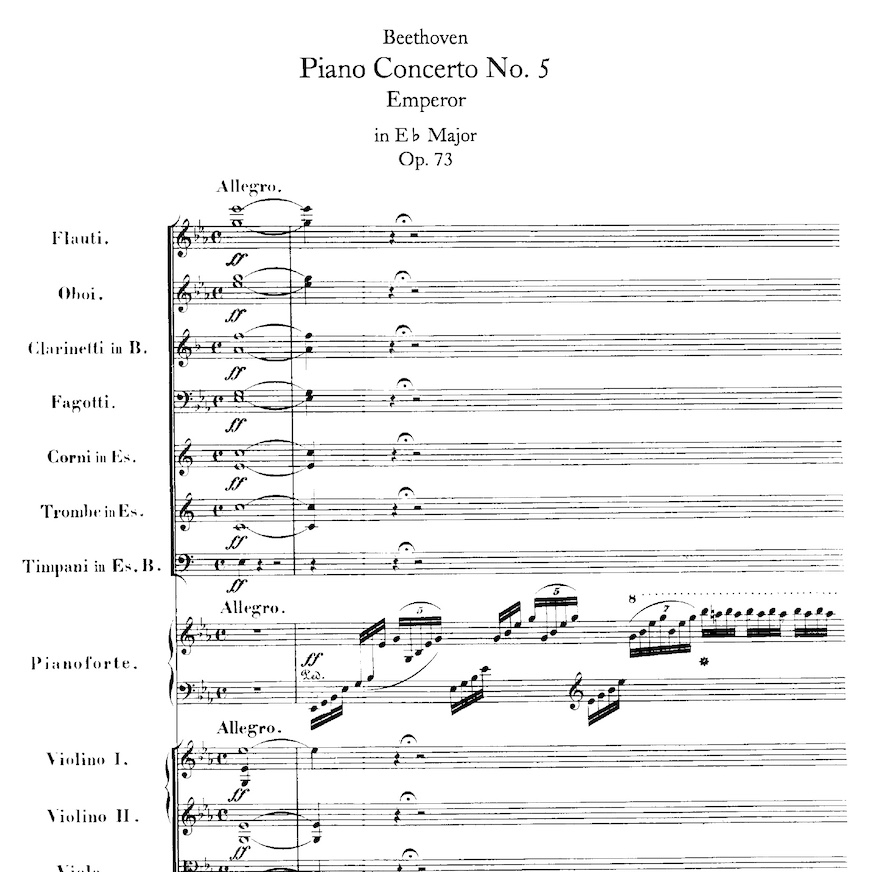

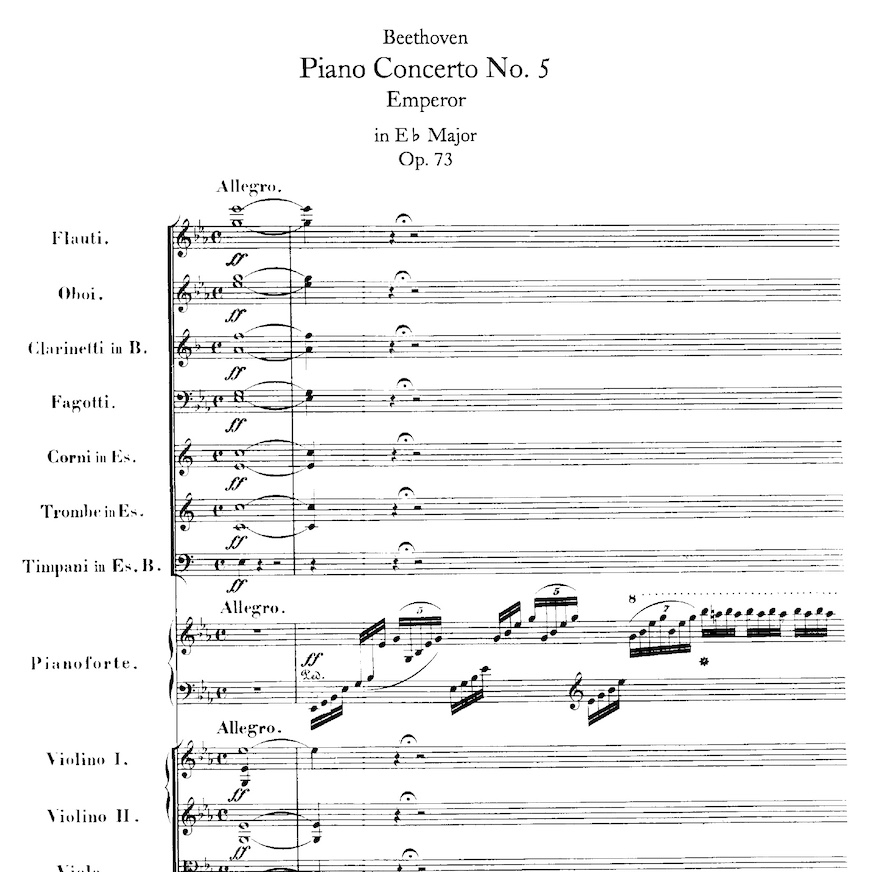

“Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte” was composed using the twelve-tone technique, but because its fundamental series is A—C—F—G♯—C♯—E; H—D—G—B♭—E♭—G♭ , with the final notes making up the I chord of E-flat minor, while it is a twelve-tone piece, it is possible to convert it into E flat major, which has the same keynote, and in fact Schoenberg’s work ends in the tonic chord of E-flat major (of course, Schoenberg had in mind Beethoven’s “Eroica”). Taking advantage of this, on the evening in question, the second work in the program, Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major (which opens with magnificent arpeggios of the tonic chord of E-flat major), began on the same note as the final note in the first work. Known by the epithet “Emperor,” this concerto was connected to the context of “Napoleon.”

“Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte” was composed using the twelve-tone technique, but because its fundamental series is A—C—F—G♯—C♯—E; H—D—G—B♭—E♭—G♭ , with the final notes making up the I chord of E-flat minor, while it is a twelve-tone piece, it is possible to convert it into E flat major, which has the same keynote, and in fact Schoenberg’s work ends in the tonic chord of E-flat major (of course, Schoenberg had in mind Beethoven’s “Eroica”). Taking advantage of this, on the evening in question, the second work in the program, Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major (which opens with magnificent arpeggios of the tonic chord of E-flat major), began on the same note as the final note in the first work. Known by the epithet “Emperor,” this concerto was connected to the context of “Napoleon.”

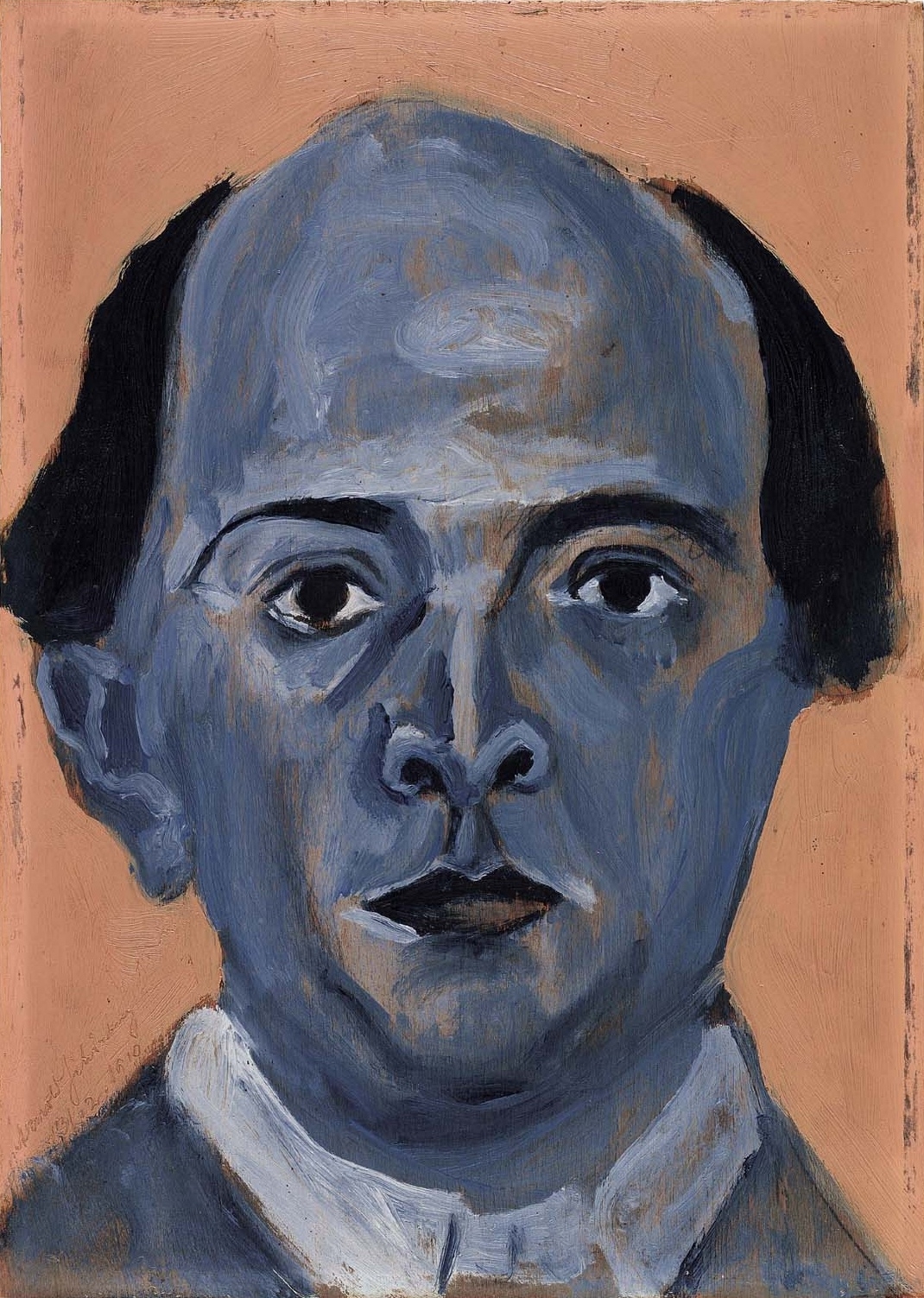

Schoenberg’s work, in which over a piano and string orchestra a narrator speak-sings a poem about Napoleon by Lord Byron that is impassioned and filled with love and hate, was composed in 1942 in the midst of World War II and likens Napoleon to Hitler. Napoleon shone as a beacon of hope for the masses but betrayed that hope and ruled as a dictator before falling from grace. As is commonly known, this process of hope and despair is reflected in Beethoven’s “Eroica” (1804). The cover of the published score of that work bears the statement, “Composed to celebrate the memory of a great man,” indicating that for the composer Napoleon was a hero (Beethoven later wrote “Wellington’s Victory” (E-flat major, op. 91, 1813) for his new hero).

Why the organizers put together such a program is clear if one knows even a little about the political situation in Europe. In last year’s Austrian legislative election, the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), regarded as a far-right party, won the most seats, since when efforts to form a government have gone nowhere. In Germany, too, the recent federal election resulted in a defeat for the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and a comeback for the old Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU)/Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU) alliance, but second place was taken by none other than Alternative for Germany (AfD). A wind of right-wing populism that is skeptical about the EU and opposed to immigration is raging over Europe. “Napoleon” was brought out as a musical symbol of this.

As if to emphasize this, as an encore before the intermission, “Rosen auf den Weg gestreut” (Roses scattered on the road), a 1931 poem by Kurt Tucholsky set to music by Hans Eisler, was sung. The German idiom “Rosen auf den Weg streuen” (to scatter the road with roses) is similar in meaning to the English “to damn with lavish praise,” and this is followed by the song’s intensely ironic refrain, “Küsst die Faschisten” (kiss the fascists).1 Intellectuals who cynically dismissed right-wing populism from on high have suddenly found themselves on the eve of fascism, just as they did a hundred years ago.

Schoenberg’s work, in which over a piano and string orchestra a narrator speak-sings a poem about Napoleon by Lord Byron that is impassioned and filled with love and hate, was composed in 1942 in the midst of World War II and likens Napoleon to Hitler. Napoleon shone as a beacon of hope for the masses but betrayed that hope and ruled as a dictator before falling from grace. As is commonly known, this process of hope and despair is reflected in Beethoven’s “Eroica” (1804). The cover of the published score of that work bears the statement, “Composed to celebrate the memory of a great man,” indicating that for the composer Napoleon was a hero (Beethoven later wrote “Wellington’s Victory” (E-flat major, op. 91, 1813) for his new hero).

Why the organizers put together such a program is clear if one knows even a little about the political situation in Europe. In last year’s Austrian legislative election, the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), regarded as a far-right party, won the most seats, since when efforts to form a government have gone nowhere. In Germany, too, the recent federal election resulted in a defeat for the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and a comeback for the old Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU)/Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU) alliance, but second place was taken by none other than Alternative for Germany (AfD). A wind of right-wing populism that is skeptical about the EU and opposed to immigration is raging over Europe. “Napoleon” was brought out as a musical symbol of this.

As if to emphasize this, as an encore before the intermission, “Rosen auf den Weg gestreut” (Roses scattered on the road), a 1931 poem by Kurt Tucholsky set to music by Hans Eisler, was sung. The German idiom “Rosen auf den Weg streuen” (to scatter the road with roses) is similar in meaning to the English “to damn with lavish praise,” and this is followed by the song’s intensely ironic refrain, “Küsst die Faschisten” (kiss the fascists).1 Intellectuals who cynically dismissed right-wing populism from on high have suddenly found themselves on the eve of fascism, just as they did a hundred years ago.

Incidentally, given that Beethoven’s works dedicated to Archduke Rudolf were all technically demanding and avant-garde (especially Piano Sonata No. 29, op. 106, (“Hammerklavier,” 1819)), he must have been extremely adept. As with Beethoven’s Piano Trio, op. 97 (“Archduke Trio,”1811), this sonata is in B-flat major. In other words, in Beethoven’s mind, Archduke Rudolf’s tonality switched from E-flat major to B-flat major. Because B-flat is the dominant of the E-flat major scale, this meant he occupied a position one rank below that of a hero, as it were. The Eisler encore at the Wiener Musikverein was in the key of G minor, G minor being the relative minor key of B-flat major. In other words, one could also interpret this encore as Beethoven “scattering roses” on the road to a short-lived hope, i.e. rule by an enlightened monarch. In fact, Beethoven ultimately expressed his desire for world peace not with E-flat major, but with D major (the final movement of his Symphony No. 9 (“Choral Symphony”) is in D major). The tonics differ only by a semitone, and after the sequence E♭—B♭—D, one wants to end on E♭. But D major and E-flat major are unrelated keys.

Incidentally, given that Beethoven’s works dedicated to Archduke Rudolf were all technically demanding and avant-garde (especially Piano Sonata No. 29, op. 106, (“Hammerklavier,” 1819)), he must have been extremely adept. As with Beethoven’s Piano Trio, op. 97 (“Archduke Trio,”1811), this sonata is in B-flat major. In other words, in Beethoven’s mind, Archduke Rudolf’s tonality switched from E-flat major to B-flat major. Because B-flat is the dominant of the E-flat major scale, this meant he occupied a position one rank below that of a hero, as it were. The Eisler encore at the Wiener Musikverein was in the key of G minor, G minor being the relative minor key of B-flat major. In other words, one could also interpret this encore as Beethoven “scattering roses” on the road to a short-lived hope, i.e. rule by an enlightened monarch. In fact, Beethoven ultimately expressed his desire for world peace not with E-flat major, but with D major (the final movement of his Symphony No. 9 (“Choral Symphony”) is in D major). The tonics differ only by a semitone, and after the sequence E♭—B♭—D, one wants to end on E♭. But D major and E-flat major are unrelated keys.

——————————–

——————————–

1. In one of the most important passages of Mozart’s The Magic Flute (Act 2, Scene 28), this idiom appears in a slightly different form. Pamina, who has been reunited with Tamino, sings, “Wherever you go, I shall be at your side. – I myself shall lead you – Love is my guide!” followed by “(Sie [=Liebe] mag den Weg mit Rosen streu’n, weil Rosen stets bei Dornen sein” (She [love] will strew the path with roses, for roses are always found with thorns). Here, this idiom is used as a metaphor for the ordeal of love. With this melody, the tune switches from F major to C major. C major is the tonality of the magic flute. In addition to Mozart’s own Freemasonry, the musical ideal of The Magic Flute is oriented towards C, not E-flat. ——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University

——————————–

“HAHN, OBONYA, GERSTEIN · SCHÖNBERG, BEETHOVEN” by the Vienna Symphony Orchestra was held at the Wiener Musikverein on February 20, 2025.

Photo by Shimizu Minoru

Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1800

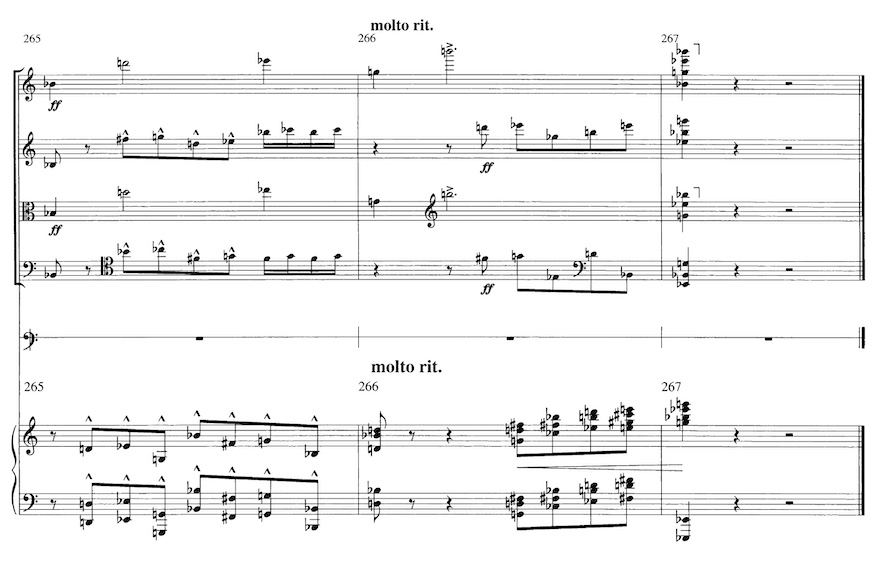

Ending of “Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte”

Opening of “Emperor”

*

In music history terms, the composition of “Eroica” in E-flat major gave this tonality a “Napoleonic” or “heroic” quality (for example, Richard Strauss’s “A Hero’s Life” is also in E-flat major). However, given that it contains three flat notes, it also symbolizes the Trinity and the sacred number three of Freemasonry, and it was also the tonality chosen by Mozart, who sought to transcend feudal society with the light of enlightened reason, for his final opera, The Magic Flute. To the extent that Napoleon represented this light, E-flat was the tonality of Napoleon the hero. Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 5 was composed in 1809, when Vienna was occupied by Napoleon’s army for the second time, and it was performed in private for the first time in 1811 with Archduke Rudolf of Austria (1788–1831), Beethoven’s pupil and patron, as the soloist. Incidentally, Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 26, op. 81a (“The Farewell,” 1809) was composed when the same Archduke Rudolf fled from Vienna to escape the ravages of war. Perhaps partly because both pieces are in E-flat major and were written just a few years apart, “The Farewell” contains passages that are almost identical to those in Piano Concerto No. 5 (especially the third movement). The epithet “Emperor” was given to this piano concerto solely because it is in E-flat major (i.e. it is “heroic”) and because it is grand, and given the circumstances of its composition, it is odd to connect this epithet with Napoleon. Both these pieces in E-flat major refer to Archduke Rudolf and were also dedicated to him. It was as if Beethoven, having been disappointed in Napoleon, instead pinned his hopes for enlightened reason on Archduke Rudolf.

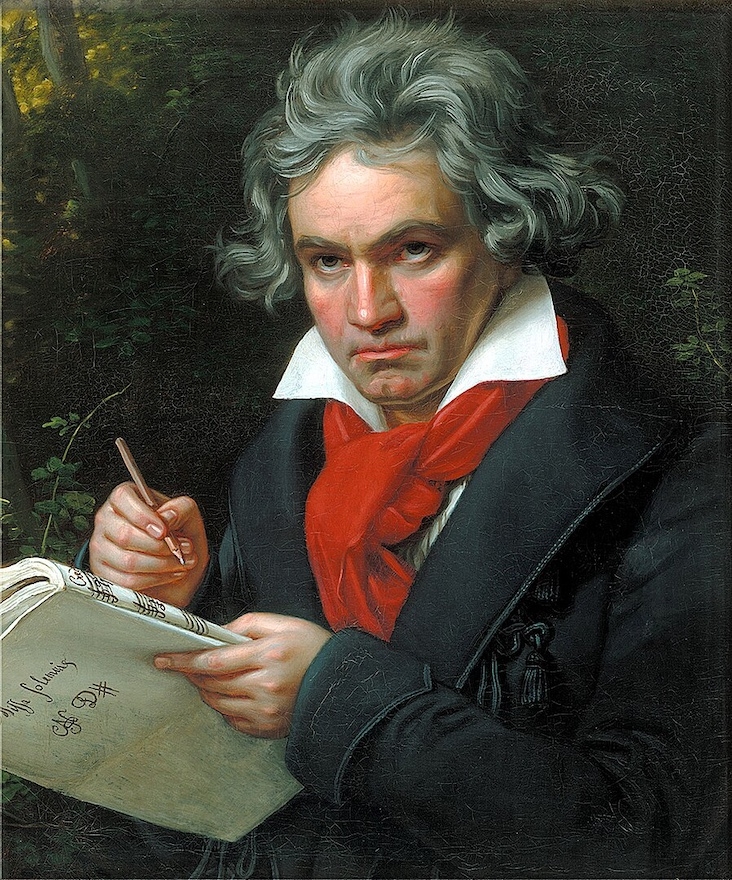

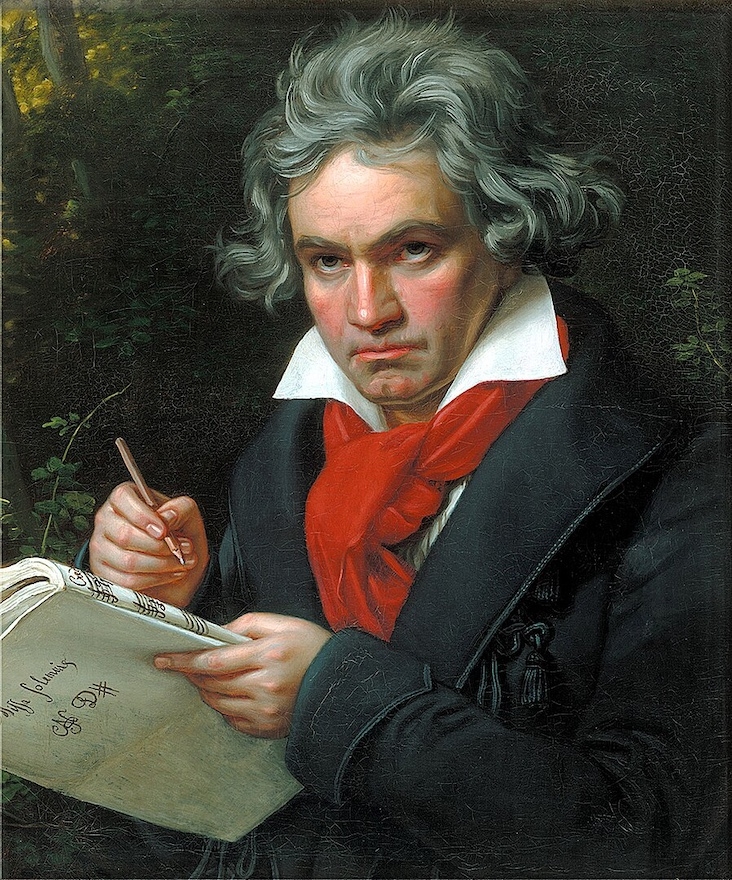

Joseph Karl Stieler, Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven when composing the Missa Solemnis, 1820

Johann Baptist von Lampi the Elder, Rudolf von Österreich, first half of 19th century

*

Beethoven’s hope and despair gave rise to “Eroica.” In the midst of fascism, Napoleon was invoked as a good example of what not to do, and in response to the right-wing populists of today, the satirical and ironic gestures directed at him were cited. But we also know that these were ineffective. Beethoven abandoned E-flat major (the light of enlightened reason, heroism) and discovered the world of D major. For Beethoven, this was a religious world (D major has two sharps, the German word for “sharp” (Kreuz) is also the word for “crucifix,” and Beethoven’s “Missa Solemnis” is in D major). What is the “world of D major” in 2025?

The Wiener Musikverein

C.Stadler/Bwag, ; CC-BY-SA-4.0.

1. In one of the most important passages of Mozart’s The Magic Flute (Act 2, Scene 28), this idiom appears in a slightly different form. Pamina, who has been reunited with Tamino, sings, “Wherever you go, I shall be at your side. – I myself shall lead you – Love is my guide!” followed by “(Sie [=Liebe] mag den Weg mit Rosen streu’n, weil Rosen stets bei Dornen sein” (She [love] will strew the path with roses, for roses are always found with thorns). Here, this idiom is used as a metaphor for the ordeal of love. With this melody, the tune switches from F major to C major. C major is the tonality of the magic flute. In addition to Mozart’s own Freemasonry, the musical ideal of The Magic Flute is oriented towards C, not E-flat. ——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University

——————————–

“HAHN, OBONYA, GERSTEIN · SCHÖNBERG, BEETHOVEN” by the Vienna Symphony Orchestra was held at the Wiener Musikverein on February 20, 2025.