Cultural Currency 34: Die tote Stadt produced by Biwako Hall

Opera—Concretizing the Universal

By Shimizu Minoru

2025.03.20

For composers, opera is like an ultimate goal of their career, and countless composers have created new works while reforming and expanding operas. Because the culmination of Western music is naturally regarded as the expression of its essence, it is fair to say that opera has been the most affected by essentialism. The “essence” of this essentialism is something rooted in the tradition and culture that has existed in Europe since ancient Greece, and is passed down hereditarily in the blood of Europeans. To put it another way, in a world in which essentialism has become consciously/unconsciously established (and this is not necessarily limited to the “white” world), opera is an extremely restricted genre where there is almost no place for non-white non-Europeans to be actively involved (Japanese singers → Madame Butterfly!).

Furthermore, because opera is the “essence” of Western music, it proliferated all over the world together with the spread of that music. In Japan, for example, the first opera performance by foreign instructors employed by the government in the Meiji period was in 1894 (Act 1 of Charles Gounod’s Faust [1859]), while the first performance by Japanese (in Japanese!) was in 1903 (Christoph Willibald Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice [1762]). Following this, from 1912 to 1918, the choreographer (!) Giovanni Vittorio Rosi/Rossi (1867–1940), who had been invited to Japan by the Imperial Theatre, organized the Japanese premieres of a number of major works including Hansel and Gretel and The Magic Flute, establishing the foundations for the acceptance of opera in Japan. Of course, these early performances were based on the assumption of an extremely limited audience, and general performances were not profitable. However, since the 1930s at the latest, for the pre-war elite, even though opera may not have been familiar, it was not something unknown. Already by 1935, Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 in D minor had been performed in its entirety for the first time by the Tokyo Academy of Music Orchestra under the baton of Klaus Pringsheim Sr. (1887–1972). In other words, there existed an audience that loved opera while appreciating works by a composer who had not written operas, even if their acceptance was poisoned by that “essentialism” that was shared by those doing the teaching and those being taught, as was commonplace at that time.

According to this essentialism, the possibility of Japanese, who do not have “blood” through which the essence of Western music flows, understanding opera is rejected from the outset. At the very most, all they can do is superficially mimic Western music and approach yet never arrive at “genuine,” “authentic” opera performances by repeating this. But if they truly believe this, what are non-European, non-white people who love opera actually doing? What do people who love musical theater based on stories that are far removed from current common sense and are in a sense absurd actually love to begin with? What is the essence of opera?

Marcel Duchamp’s gravestone bears the famous epitaph, “D’ailleurs, c’est toujours les autres qui meurent” (“Besides, it’s always the others who die”). These words, which seem to be so dehumanizing, actually touch upon the reality of death. All that is known to us is the death of others. Our own death is (or should be) something we experience only when we die, and that experience is not exchangeable. It is something unshareable that we have no choice but to experience alone. For mortal beings, death is the most universal event, but this “universality” is not an essence common to all of us. To varying degrees, life is full of such universality (foreign languages, musical instruments, sports, love, marriage, parenthood, etc.). What lies at the essence of opera (and art in general) is also this universality, but this universality exists only insofar as opera lovers find it in the “universality” they have experienced. Insofar that it is the sharing of the unshareable, the universality of artworks is a kind of miracle.

Marcel Duchamp’s gravestone bears the famous epitaph, “D’ailleurs, c’est toujours les autres qui meurent” (“Besides, it’s always the others who die”). These words, which seem to be so dehumanizing, actually touch upon the reality of death. All that is known to us is the death of others. Our own death is (or should be) something we experience only when we die, and that experience is not exchangeable. It is something unshareable that we have no choice but to experience alone. For mortal beings, death is the most universal event, but this “universality” is not an essence common to all of us. To varying degrees, life is full of such universality (foreign languages, musical instruments, sports, love, marriage, parenthood, etc.). What lies at the essence of opera (and art in general) is also this universality, but this universality exists only insofar as opera lovers find it in the “universality” they have experienced. Insofar that it is the sharing of the unshareable, the universality of artworks is a kind of miracle.

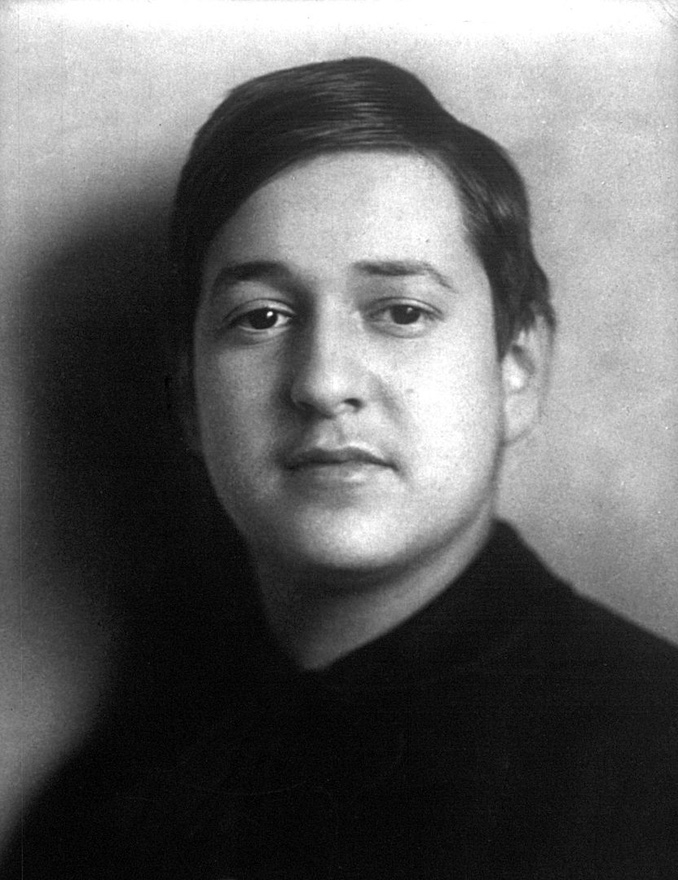

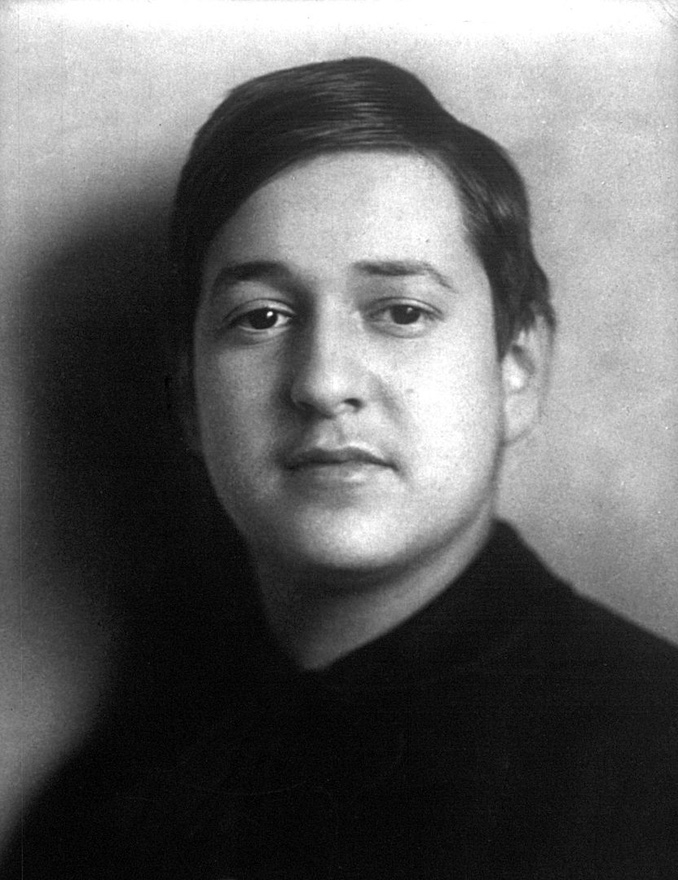

Firstly, Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s (1897–1957) Die tote Stadt, which premiered in 1920, was the third (!) opera written by the highly gifted and popular composer at the age of 23. The protagonist (Paul), who is unable to come to terms with the death of his ideal wife (Marie), tries to love a dancer (Marietta) who looks exactly like her. Ultimately, having awakened to reality after trying to kill Marietta in a vision, he recognizes that Marie is in the past and begins a new life. Die tote Stadt was a huge success, making Korngold known to the world as an opera composer. Life was smooth sailing, but when Nazi Germany annexed Austria in 1938, the Jewish composer fled to Hollywood, where he already had contacts through his work. Korngold likened movies to opera and is recognized as having innovated film music through the use of orchestration, which was still new at the time. If Die tote Stadt sounds a little “film music-like,” then the opposite is actually true, in that modern-day film music more or less originated with Korngold.

Firstly, Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s (1897–1957) Die tote Stadt, which premiered in 1920, was the third (!) opera written by the highly gifted and popular composer at the age of 23. The protagonist (Paul), who is unable to come to terms with the death of his ideal wife (Marie), tries to love a dancer (Marietta) who looks exactly like her. Ultimately, having awakened to reality after trying to kill Marietta in a vision, he recognizes that Marie is in the past and begins a new life. Die tote Stadt was a huge success, making Korngold known to the world as an opera composer. Life was smooth sailing, but when Nazi Germany annexed Austria in 1938, the Jewish composer fled to Hollywood, where he already had contacts through his work. Korngold likened movies to opera and is recognized as having innovated film music through the use of orchestration, which was still new at the time. If Die tote Stadt sounds a little “film music-like,” then the opposite is actually true, in that modern-day film music more or less originated with Korngold.

Just because the music is “film music-like” by no means makes it plain and simple. Due to the skillful orchestration it is not particularly conspicuous, but the score is complex, including chords daringly incorporating unconventional sounds tending towards atonality and noises intentionally deviating from tonality. But the City of Kyoto Symphony Orchestra captivated the audience with its lively, clear playing. Under the baton of Ban Tetsuro, this laid-back group of musicians exhibited a keenness as if it had been charged with 250V. If I were to award top marks to an aspect of this performance, I would award it to the orchestra.

Just because the music is “film music-like” by no means makes it plain and simple. Due to the skillful orchestration it is not particularly conspicuous, but the score is complex, including chords daringly incorporating unconventional sounds tending towards atonality and noises intentionally deviating from tonality. But the City of Kyoto Symphony Orchestra captivated the audience with its lively, clear playing. Under the baton of Ban Tetsuro, this laid-back group of musicians exhibited a keenness as if it had been charged with 250V. If I were to award top marks to an aspect of this performance, I would award it to the orchestra.

Next, Iwata’s twofold production consisted of an update of Kuriyama’s production and a memorial to that production itself. As part of the former, he turned the start of Act 2 into a wonderful scene change in which the stage emerged from a fantastic play of light involving the intersection of veils and video. In the latter, the Kuriyamas were remembered by superimposing the history of Japanese opera, which has been developed in a sustained manner while grappling with deep-rooted essentialist prejudices, over the story of the protagonist, Paul (Kuriyama Masayoshi). The person unable to come to terms with the death of their ideal (“opera” as the essence of Western music) and try to love it by replacing it with something that looks exactly like it (Japanese opera as a copy of “opera”), only to awaken to reality after trying to kill this copy in a vision, recognize that “opera” is in the past and tread a new path (opera as the concretization of the universal), is the modern-day director. Kuriyama is perhaps being remembered as a member of the last generation to be shackled by essentialism. In the scene in Act 3 where Marietta (Japanese opera) and Paul (Kuriyama Masayoshi) confront each other, if my memory serves me correctly, the shadow of Gaston (mourner? reminiscer?) closely observes the exchange without uttering a word. When I looked up, I saw that without my realizing it the moon in the background had acquired a rectangular frame and turned into a tilted rising sun. At the end, together with a lit candle, Kuriyama’s original stage set was presented unadorned.

Next, Iwata’s twofold production consisted of an update of Kuriyama’s production and a memorial to that production itself. As part of the former, he turned the start of Act 2 into a wonderful scene change in which the stage emerged from a fantastic play of light involving the intersection of veils and video. In the latter, the Kuriyamas were remembered by superimposing the history of Japanese opera, which has been developed in a sustained manner while grappling with deep-rooted essentialist prejudices, over the story of the protagonist, Paul (Kuriyama Masayoshi). The person unable to come to terms with the death of their ideal (“opera” as the essence of Western music) and try to love it by replacing it with something that looks exactly like it (Japanese opera as a copy of “opera”), only to awaken to reality after trying to kill this copy in a vision, recognize that “opera” is in the past and tread a new path (opera as the concretization of the universal), is the modern-day director. Kuriyama is perhaps being remembered as a member of the last generation to be shackled by essentialism. In the scene in Act 3 where Marietta (Japanese opera) and Paul (Kuriyama Masayoshi) confront each other, if my memory serves me correctly, the shadow of Gaston (mourner? reminiscer?) closely observes the exchange without uttering a word. When I looked up, I saw that without my realizing it the moon in the background had acquired a rectangular frame and turned into a tilted rising sun. At the end, together with a lit candle, Kuriyama’s original stage set was presented unadorned.

If there was one aspect of this performance that did not do so well it was the singers. Paul’s voice was not powerful enough and he could not sustain the high notes, thus he was overshadowed by Marie. Marie was not bad, but I wanted her to overwhelm the audience more. Fritz, the Pierrot, was the best, and his performance in Act 2 of the aria (“Mein Sehnen, mein Wähnen” – My yearnings, my fantasies), which follows a reference to Wagner’s Das Rheingold, resonated with Iwata’s production and left a deep impression.

If there was one aspect of this performance that did not do so well it was the singers. Paul’s voice was not powerful enough and he could not sustain the high notes, thus he was overshadowed by Marie. Marie was not bad, but I wanted her to overwhelm the audience more. Fritz, the Pierrot, was the best, and his performance in Act 2 of the aria (“Mein Sehnen, mein Wähnen” – My yearnings, my fantasies), which follows a reference to Wagner’s Das Rheingold, resonated with Iwata’s production and left a deep impression.

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University Die tote Stadt was performed on March 1 and 2, 2025, at Biwako Hall Center for the Performing Arts, Shiga. This text was written based on viewing the March 2 performance.

*

The reason I have gone on at length about this subject is that the performance of Die tote Stadt (The Dead City) produced by Biwako Hall was also a performance in memory of the opera director Kuriyama Masayoshi (1926–2023), who staged this opera for the first time in Japan in 2014. As well as reproducing Kuriyama’s stage direction from 11 years ago, the director of this performance, Iwata Tatsuji, also superimposed on it the history of opera direction in Japan as exemplified by Kuriyama.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress)

Kyoto Symphony Orchestra at rehearsal

Ban Tetsuro

Iwata Tatsuji

Kuriyama Masayoshi

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University Die tote Stadt was performed on March 1 and 2, 2025, at Biwako Hall Center for the Performing Arts, Shiga. This text was written based on viewing the March 2 performance.