Cultural Currency 35: The City of Kyoto Symphony Orchestra’s 700th Subscription Concert

En Blanc et Noir

By Shimizu Minoru

2025/05/17

Kyoto Concert Hall

(c)City of Kyoto Symphony Orchestra

Recent subscription concerts by the City of Kyoto Symphony Orchestra have consisted of works centering on a single, common theme. Being aware of this theme while listening to the performances makes the listening experience richer. For example, for the previous subscription concert (the 699th, featuring Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs, and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 in B Minor, op. 74 (“Pathétique”) and Hamlet overture-fantasia, op. 67), the final works written by the two composers were performed together in such a way that calmly accepted death (Strauss) and life ended with one’s own hand (the theory, contradicted by biographical research, that Tchaikovsky committed suicide) formed a powerful contrast. Believing that the truth lies not in the composers’ life stories but in their very music, conductor David Axelrod construed the muted brass in the Hamlet overture-fantasia as signifying the need to remain mute, i.e. silent, to stifle the truth, and interpreted the same muted playing in the “Pathétique” as expressing the composer’s anguish at not having been able to openly declare his homosexuality, overwhelming the audience with a madly passionate performance.

As was made clear at the beginning of the program, the theme of the 700th subscription concert, featuring Heinz Holliger’s Elis, Drei Nachtstücke (version for piano solo and version for orchestra), orchestral arrangements by Holliger of two late piano works by Franz Liszt (Nuages gris and Unstern!), Toru Takemitsu’s Dream/Window and Schumann’s Symphony No. 1 in B-flat Major, op. 38 (“Spring Symphony”), was solo piano and orchestral versions of the same pieces. This addressed the question of arrangements that can be seen often throughout the history of music, the mysterious interchangeability of piano scores (a world of white keys and black keys) and orchestral scores (a world of instruments possessed of various tone colors) and ultimately the question, “What is color in music?”

There are many figures of speech linking colors and sounds. A chromatic scale is a musical scale with color, and harmony can refer both to the harmony of colors and of chords. Similarly, in Kandinsky’s Über das Geistige in der Kunst (Concerning the Spiritual in Art), colors are treated as entities that “resonate” (klingen). Generally, the most fundamental element connecting music and other fields (mathematics, astronomy, architecture) is “proportional relationships.” It is not unusual for specific proportional relationships to transcend different genres. The structure of Guillaume Du Fay’s motet Nuper rosarum floress is based on the proportions of the pillars of the Florence Cathedral, for example, and Fibonacci sequences are used in Bartók’s Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion. Sounds and colors are also connected not simply by the tonal colors of instruments, but by certain relationships. Similarly, the concept of “tone-color-melody” discussed by Schoenberg at the end of his Harmonielehre (Theory of harmony, 1911) does not involve different instruments playing the individuals sounds of a melody. The tones of sounds are structural and originate in proportional relationships, something that was particularly true in the case of his tonal music. This is because the essence of its sense of color lies in modulation. In tonality, because there is a hierarchy of importance among the twelve notes of a single octave, a gravitational field is formed around the single most important, central note. Tonal music is “cadential” (from the Latin cadere, “to fall”) music that constantly seeks to fall towards this central note, and the understanding of music is none other than the recognition of the direction of this fall. In this context, modulation means music that is falling in accordance with one gravitational field (tonality) changing so that the direction of its fall is towards a different gravitational field (a different tonality), or in other words a structural change of direction.

The reason why the world of just black and white (the piano) and the colorful world of the orchestra are interchangeable is because the color of tonal music originates not in the tone colors of instruments, but in the structure (the auditory gravity) of tonality. If tonality collapses, such a sense of color is impossible. Beginning with Liszt’s late piano works, many composers around the turn of the century tried to escape from gravity through atonal music, which is to say a new musical structure, but for all of them “color” was an important concept. Atonal (i.e. zero-gravity) music demands new principles of color. The pursuit of atonality was the pursuit of a new kind of tone color.

In order to realize atonality, equal importance needs to be given to the twelve notes of a chromatic scale. As is commonly known, Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique was a method of ensuring the frequency of the appearance of each note was equal by creating tone rows of the twelve notes of an octave and composing music by repeating them horizontally/vertically. At this time, composers realized that the tone of each work was influenced by the interval relationships among the notes making up the tone rows. For example, from tone rows containing many of the consonant intervals such as perfect fourths and fifths that represent the principle of tonality arose pseudo-tonal tone colors. All-interval twelve-tone rows containing all eleven intervals within the octave gave rise to tone colors with the least sense of tonality. In Vom Wesen des Musikalischen (“On the essence of music,” 1920), Josef Matthias Hauer, another theorist of twelve-tone music, wrote as follows: “The understanding of tone-color always requires a creative musical imagination, because ‘hearing colors’ … arises in humans purely ‘spiritually.’” The tones of notes arise from the proportional relationship between individual notes, or in other words from intervals. Hauer’s most fundamental equation was intervals = color. “Musical color theory is nothing more than interval theory. The myriad intervals within an octave form the tonality of color in music.” (Über die Klangfarbe (“About tone-color,” 1918))

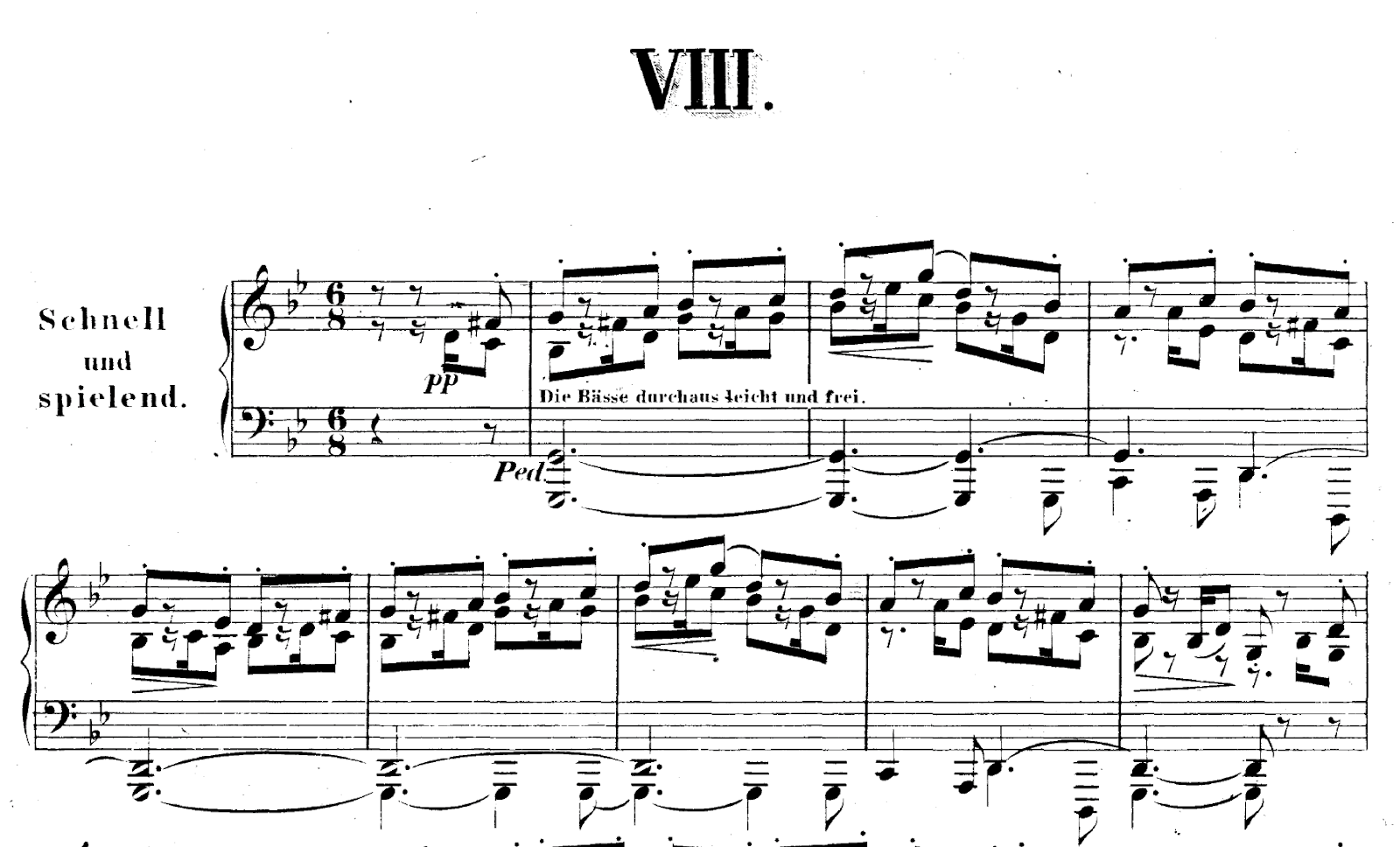

One could say that Holliger’s arrangements are translations of such color principles of atonal music into the color tones of an orchestra. With Elis, which is based on a poem of the same title by Georg Trakl, he painted separately for piano and orchestra the “golden,” “rosy,” “blue” and “black” colors that are characteristic of the poet. The arrangements of the two works by Liszt were beautiful and possessed of a subtlety reminiscent of Webern’s orchestrations. On the other hand, the Schumann symphony is a euphoric work that according to legend was written in just four days in 1841 after Schumann was finally able to marry Clara Wieck following a lengthy legal wrangle, though partly because it is Schumann’s first symphony, the peculiar writing technique that can be heard in the composer’s earlier piano works reveals itself throughout. In other words, it is almost like a piano piece arranged for orchestra. This is perhaps most evident in the appearance in the second theme of the fourth movement of the theme from the beginning of the eighth movement of Kreisleriana, Schumann’s masterpiece from 1838 when he was agonizing over not being able to marry Clara, in the same tonality.

The second theme of the fourth movement of Schumann’s Symphony No. 1 (“Spring Symphony”) appearing in the woodwind section.

The theme from the beginning of the eighth movement of Kreisleriana.

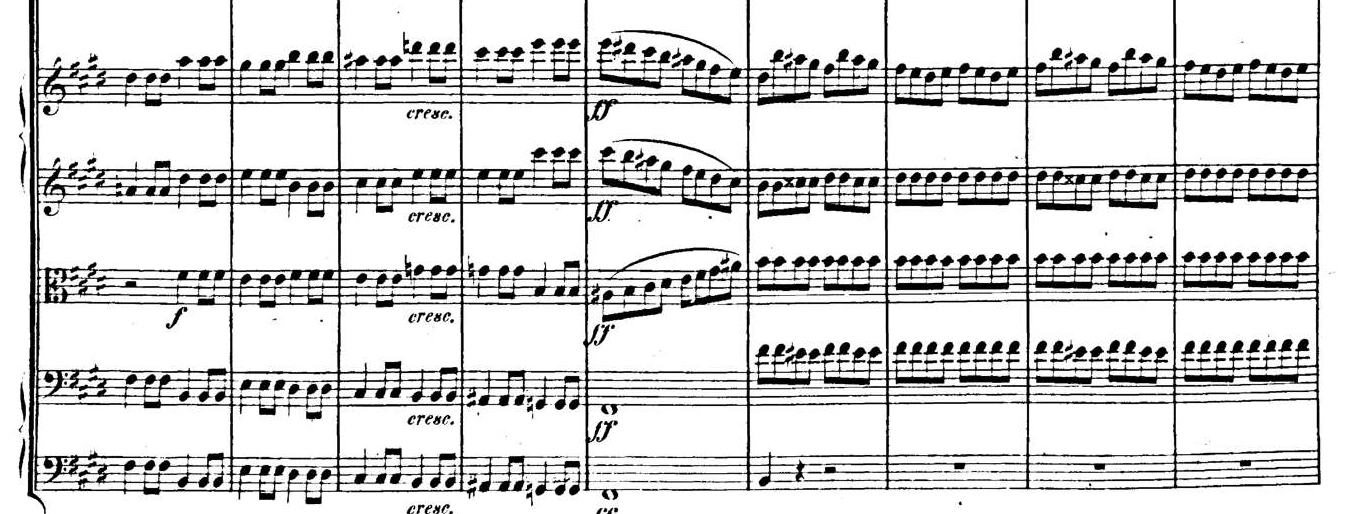

The most striking performance in the latest CKSO subscription concert was this “Spring Symphony.” Perhaps it is my prejudice, but light, bright, heavenly music such as Mozart and Mendelssohn (and Schumann’s “Spring Symphony”) cannot be said to be the forte of Japanese orchestras. By this I mean that the awareness of “trying to match” the sound pattern typical of classical music that moves around meticulously and rapidly (ta-la-li-la, ta-la-li-la, ta-la-li-la, ta-la—li-la…) is too strong, resulting in a subtle emphasis on the first beat (ta-la-li-la, ta-la-li-la, ta-la-li-la, ta-la-li-la…), and this becomes a brake causing the original light, soaring music to turn into a military march.

From Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream overture

This time (though, possibly due to the influence of Dream/Window, the beginning of the first movement was somewhat dreamy (?) and heavy), this was not the case at all, and while indeed the soaring of the idealistic A Midsummer Night’s Dream was perhaps missing, there was a keen lightness that was adequate for a joyful Schumann symphony. Conductor Holliger reminded us once again of the appeal of Schumann’s “overly piano-like” symphony.

(c)City of Kyoto Symphony Orchestra

[*1] Toru Takemitsu’s Dream/Window was added to mark the 700th subscription concert and is therefore beyond the scope of the theme of this essay. The 700th Subscription Concert

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University