Heiner Goebbels Lecture “Aesthetics of Absence”

Edited by William Andrews

Photo by Takuya Matsumi

Thank you for this wonderful invitation.

First I would like to give some insights into my productions and what I call the “Aesthetics of Absence.” My latest production, for example, was Louis Andriessen’s De Materie (The Matter), which I staged in 2014. I sometimes call this work a Copernican shift of the opera, because it is the opposite to any other opera I know: the human beings are not at the very center of attention but rather the reflection of the relationship between mind and matter. The themes are physics, political emancipation, religion, sexuality, art history, love, and death. Except at the very end, there are no performers in the fourth act of Andriessen’s score. In my production I tried to choreograph 100 sheep in a huge vast space with a Zeppelin circling above them. It was one of my most moving experiences as a director and, I think, a very moving experience for the spectators, too. Since there were no human beings on stage, it meant you were seeing something that cannot be explained. It is hard to understand how it works, even for us. We only knew how to get the sheep off stage by making a rattling sound with a food box. This is a good example of the “Aesthetics of Absence.” And it is not symbolic. There’s a certain relation between these two elements, the sheep and the Zeppelin. Two forces are in a counterpoint and they open up a space for imagination. And this is what you find a lot in my work.

Louis Andriessen: De Materie (2014)

Photo by Wonge Bergmann / Ruhrtriennale

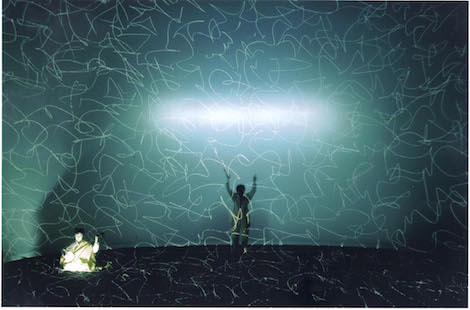

We will show Black on White in this space in October and there are a number of points about this production I wish to explain. Firstly, you can never be sure of its genre or format. It starts as a kind of installation: somebody writing and others making sounds while preparing instruments. Then all of a sudden, the musicians come on stage to play a concert, one after another, sitting with their backs to the audience. This is also part of what I’m generally interested in: not to show the obvious, not to show the expected. Even in this second scene, the concert, it is a strange formation for a concert. A few minutes later, a new category starts when the scene turns into a kind of game or play. The biggest challenge for me in this production was working with such a wonderful ensemble of musicians. I know they can play anything from Stockhausen to Pierre Boulez, but I tried to challenge them with different tasks.

“Ye who read are still among the living; but I who write shall have long since gone my way into the region of shadows.”

This is the beginning of the story Shadow by Edgar Allan Poe. It reminds us of what Roland Barthes wrote one century later in “The Death of the Author,” but also of the fact that Heiner Müller, the German author and my long-time collaborator, died during rehearsals. Black on White, thus, became a requiem for him. What I mean by “absence” starts very much with this work. The musicians sing, read, move, laugh, play games and music, and you see them in a very modest and humble, untheatrical way of performing. This is already the opposite of what usually is considered as the basic assumptions of theater, such as presence, intensity, expression, and addressing the audience. It’s a very intense and moving experience, but it’s not working with the classical registers of theater. It has more to do with a landscape painting perhaps, where you as a viewer can discover what you are interested in. You can focus yourself in this landscape of 18 musicians. Here, absence also means that there is no center. The center is the dead who are not on stage. There is no special figure, protagonist, actor, dancer, singer, or soloist. There is only a collective protagonist—the ensemble of musicians.

Black on White (1996)

Photo by Christian Schafferer

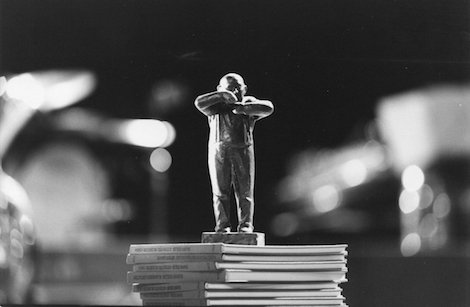

Eislermaterial was dedicated to a German composer in the first half of the 20th century, Hanns Eisler, who worked very closely with Bertolt Brecht. It is more obvious in this setting that the center of the stage is empty all the time. Usually in a concert the conductor is the center, but this piece has no conductor, just a little statue of Hanns Eisler in the middle of the stage. The musicians sit on three sides of the empty stage, which makes playing very difficult. They also have to do things which they are not so good at, such as singing, playing instruments other than their usual instruments, and so on. When playing such complex music over such a big distance, the music becomes quite fragile and shaky. I made it very difficult for them to be good musicians, but they like the challenge. They love to perform it and keep saying “This is our Haydn,” as Joseph Haydn’s music is meant to be the most difficult thing to play, though it seems so easy.

The groups of musicians—the strings, the brass, and the wood—are also not sitting together. When they have to play something very intimate, they have to communicate over this huge distance and the difficulty and communication becomes visible to the audience. For the composer, Hanns Eisler, who was a very political composer, it was always very important to find the right attitude to perform his music. Here the musicians have to be totally focused and so cannot address anything to the audience. And this is exactly what attracts the attention and perception of the public.

Eislermaterial (1998)

Photo by Matthias Creutziger

A drama in the 19th and 20th centuries was a story between representative figures on stage, performing psychological conflicts with each other. The audience could identify with one side or the other, but since the end of the 20th century the notion of “drama” has shifted more to being a drama of perception, and the stage away from being one of a representation but to a reality in its own right.

Originally I tried to reflect and change the traditional form of the concert. When I started with my first so-called “staged concerts” in the 1980s, I thought I was inventing a new genre. But in fact it was Harry Partch who had already invented this idea of staged concerts without a conductor in the 1950s and 1960s in California. Harry Partch thought that the European well-tempered system of tuning is mankind’s greatest crime. He believed that the 12 tones of the Western music scale were not enough to express all the colors he was looking for. Instead, he developed his own microtonal scale with 43 steps per octave. And since you cannot play this music on normal instruments, he built all his instruments himself. In Partch’s opera Delusion of the Fury (1964), the first act is based on a Japanese Noh play from the 15th century and the second part on an African tale. I staged it for the first time outside the US as another work without a center, but the visibility of instruments as the main part of the staging had actually already been pioneered by Partch. Again, the absence of the conductor here enables us to look into this landscape of musicians, instruments, communication, and activities. Another aspect in this opera is the absence of text. Though Partch used those two narratives, there’s only about 25 English words in one hour of music. He believes only in the artistic experience, in the experience of what we hear and see, without words.

Harry Partch: Delusion of the Fury (2013)

Photo by Wonge Bergmann / Ruhrtriennale

Before my work Stifters Dinge and staging De Materie, I experienced the prolonged absence of an actor in Eraritjaritjaka . It has two important moments when the actor disappears. One is when he leaves the stage after a reflection on life. Just an object is left on stage, a tiny little idyllic house in the center, with little windows lit and smoke coming out of the chimney. And at the same time, there is a massive noise. So it is actually a prop that becomes the protagonist, or the sound, or the counterpoint between prop and sound, or the space between what we see and hear.

A few scenes later, the actor performs a large and virtuous monologue on the conductor as a metaphor for totalitarianism, and what effect he has on the orchestra and audience. After the monologue he leaves the stage again. A camera follows him through the lobby, outside the theater and into a car. He drives away in the car for about 6 minutes. After this, he walks a bit through the city, arrives at his apartment and does very everyday things like reading the newspaper, writing notes, cooking, sorting his laundry, watching TV, and so on. You follow the live video projected on the white backdrop of the stage. And you can see he is doing everything in accordance to the music, a string quartet by Maurice Ravel performed live on stage. You notice the synchronicity. The string quartet is playing live on the stage and you see in the background of the kitchen a clock showing the very same time as while you sit in the audience. Similar to the question of “Who is choreographing the sheep?”, the audience is very intrigued in the mechanics of the work. How can he be synchronized with the music? Where is he? This goes on for 40 minutes until finally he goes upstairs and, while quoting words by Elias Canetti, he opens one of the windows and, with a shock, the audience becomes aware that he is on the stage again. Or has he never been away?

This is what I call a drama of perception. It’s a drama of the medium, a drama of the music all of a sudden being in the space. It’s a drama of a performer we assumed being far away, but all of a sudden we see him in the window. It’s also a complex twist of the inside and outside of this house, while all the time the center of the stage is empty.

Eraritjaritjaka (2004)

Photo by K. Bielinsky

A few years before Eraritjaritjaka, I made another piece, with the same wonderful actor, André Wilms, called Max Black. Here the idea of absence is translated and divided into a presence of sounds and objects. He’s a scientist in his laboratory. All the sounds in this space have their own life. The echo of the sounds he produces in his experiments don’t disappear; they choreograph his movements and words.

This is an element you see a lot in my work. I try to look for forces that can create difficulties for the musicians in Eislermaterial. Or the music that choreographs the movements and activities of the actor in the kitchen in Eraritjaritjaka. Or the benches in Black on White, which choreograph all the movements of the musicians.

Max Black (1998)

Photo by Christoph Kniel

In 2008, I worked with The Hilliard Ensemble, a quartet of British vocalists famous for the music of Dufay and Perotin. In I went to the house but did not enter , the absence is actually the absence of what they are known for. In the first 15 minutes they don’t sing; they are completely silent. They have other things to do. The first act is based on T.S. Eliot’s The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Only at the very end of this half-hour did they sing beautifully. There is also an absence of colors. Everything is many shades of gray, between black and white.

I went to the House but did not enter (2008)

Photo by Wonge Bergmann / theatre vidy

I get much inspiration from the American writer Gertrude Stein. She polemically once said, “Everything which is not a story could be a play.” She meant that theater can be much more than just a story. Theater can work on so many other levels. It can be a story of the light, the space, the movement, the choreography, the words, or the music and sounds. You could define absence in her work as an absence of making sense. I used her words in a piece called Hashirigaki, which I created for three female performers, based on a book by Stein called The Making of Americans in which she proposes a completely different use of language. It’s a very musical, repetitive, meditative use of language. I used music from The Beach Boys and traditional Japanese music performed by Yumiko Tanaka.

Hashirigaki (2000)

photo by Mario del Curto / theatre vidy

Let’s recapitulate these different concepts of absence so far. It can be a direct disappearance of the actor or performer from the center of attention, or even from the stage altogether. It can be a division of presence among all the things happening on stage. For example, the actor who had to divide his presence with the presence of the objects and the sounds in Max Black. It can be a division of the spectators’ attention to a collective protagonist, performers who very often hide their individual significance by turning their backs on the audience. Or it can also be the disappearance of the individual significance of the singers, as in The Hilliard Ensemble, when they create a sort of fifth voice. It can be the de-synchronization of listening and seeing, the separation between the visual stage and acoustic stage. It can be the creation of spaces, spaces to discover and spaces in which emotion, imagination, interpretation, or reflection can actually take place, not presented by the artists on stage but experienced by the audience. It can be the abandonment of dramatic expression or theatricality. Or it can be an empty center, the absence of a visually centralized focus. It can also be the absence of what we call a theme or linearity in the storytelling. Again I’d like to quote Gertrude Stein:

“What is the use of telling a story since there are so many, and everybody knows so many, and tells so many, so why tell another one.”

The absence can be understood by avoiding the things we expect, the things we have seen already, the things we have heard already, and all those things that are usually done on stage. Instead, the eye and the mind of the spectator should be able to wander around and focus on what he or she is interested in.

Stifters Dinge (Stifter’s Things) has no performers but five pianos, water, rain, fog, ice, stones and three pools. Above these three pools, four curtains go up and down in an unpredictable rhythm, while water runs from tanks into the pools. We hear voices recorded in 1904 in Papua New Guinea. The waves of water are reflected and mirrored in the curtains. Again, we have this separation of we see and what we hear. Our perception wants to connect these two stages. This desire actually spurs the imagination.

Stifters Dinge (2007)

Photo by Mario del Curto / theatre vidy

Once a woman in Belgrade came to me after the show and told me that she “saw God” in this scene with the curtains, light and waves. Somebody else said, “Thank you for the sundown at the beach.” Both are true. Everything an audience sees and feels is true. What the set and light designer Klaus Grünberg and I do is not meant to be a symbol to be understood in a very specific way. For us it’s only a projector, curtain and waves. What interests me in this scene even more is the upside-down relationship between light and voice and sound. When the light goes on, we hear the shutter and then the voice of this ethnographic recording reacting to it with a scream. So acoustically, the light also has a very active role in this dialogue.

Adalbert Stifter was a writer in the 19th century. It is quite amazing how he articulates our attention already in his writing by deceleration. He is famous for his very detailed descriptions, especially of what he doesn’t know, which he calls “things” (Dinge). It can be an object or somebody from a remote culture; a natural phenomena or an ecological catastrophe. In the story in my production, it is an icefall in a forest during winter. Only after about 10 minutes, after we hear this voice reading a story by Adalbert Stifter, the pianos are finally seen and give a “concert.”

It is the same deceleration we know from Stifter’s writings. My piece was perceived as ecological or ethnographical, which was not the intention but a result of the creative process in which we looked at the water and waves, and the reflections. Those elements ask for a certain timing of perception. At the end of the piece, when the water has changed, we hear an ethnographic recording from Greece. Again, it is not a scene with a symbolic function for us as producers. It is rather an offer, an invitation to meditate, reflect and imagine.

Stifters Dinge – The Unguided Tour (2013)

Photo by Wonge Bergmann / Ruhrtriennale

People who speak to me after performances have very different ways to interpret this image, since the music and the artworks and the voices in this piece simultaneously suggest different time zones, I sometimes also call the aesthetic experience an “anachronic experience,” which is not necessarily connected to a specific idea of “the contemporary.” The “contemporary” is how we see and perceive these works.

Edited by William Andrews

(Publication: July 31, 2017)Heiner Goebbels www.heinergoebbels.com

Heiner Goebbels / Ensemble Modern – Black On White –

Oct.27 [Fri],2017 -Oct.28 [Sat],2017 / Kyoto Art Theater Shunjuza

Visit the website for more information:

Kyoto Art Theater Shunjuza

KYOTO EXPERIMENT 2017