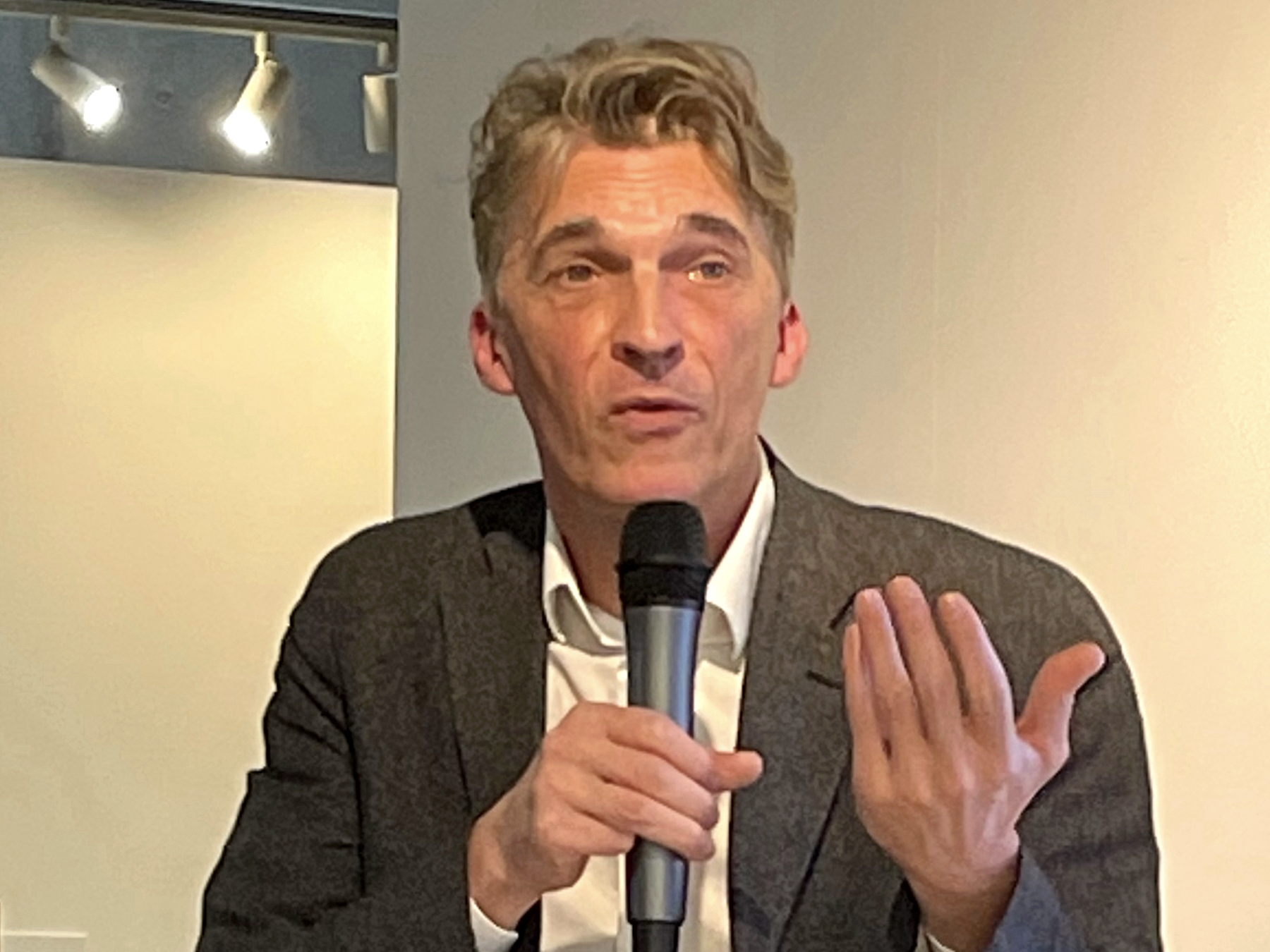

About Nicolas

Shimabuku

Last September, I met Nicolas Bourriaud in Paris for the first time in many years. I first met him in 1998 when I started showing my works at a gallery in Paris,

Air de Paris, and since then he has been coming to see my exhibitions almost every time. Occasionally we have dinner together at mutual friends’ places.

Passing through many exhibitions, Nicolas has intimate conversations with various artists sitting knee to knee with them. People call him a theorist or critic and Nicolas himself a curator, but to me he may be more aptly described as an anthropologist or field researcher. A curator per se should be like that. Nicolas creates his own exhibitions, focuses on the works, and weaves his own words while staying close to the artists. He himself once told me that he needs to curate exhibitions in order to think. When I was asked to participate in

the Taipei Biennale curated by Nicolas in 2014, he simply said, “Surprise me,” so I decided to exhibit

My Teacher Tortoise a work of a living tortoise.

On one occasion, Nicolas asked me for advice, he said, “I’ve been invited by

Art Collaboration Kyoto, an art fair in Kyoto, to give a talk in November. I wonder if there is anything else I can do?” I immediately thought of introducing him to Asada-san and Ozaki-san, and that a talk event with them would definitely be something interesting. Unfortunately, due to scheduling conflicts, it did not happen as an open discussion, but we ended up having dinner together. While choosing a place to eat, I asked him, “Is there anything you can’t eat?” and he said “I can eat anything. Even if it’s something I haven’t eaten yet!” So I prepared appetizers such as sea grapes and

jimami tofu from Okinawa where I live. Before dinner, we engaged in a short conversation. The discussion between Nicolas, Asada-san and Ozaki-san was as intense and interesting as I had expected, and I was very happy to be there.

“There were a lot of misspellings in Documenta 15”

Ozaki What do you think about the 2022 edition of

Documenta (d15)? I saw your tweet supporting its artistic director

Ruangrupa when they were accused of antisemitism. They have been strongly influenced by your idea of relational art. But apart from that, I really want to know your frank opinion about it.

Bourriaud It’s funny because I started reacting to the accusation against Ruangrupa before I actually saw d15 in August, after the opening. My main impression was a sense of monotony. If you make a movie, you don’t accumulate the same kind of scenes all along the movie. And if d15 was a movie, it would be a kind of slow traveling upon a quite monotonous landscape. At the beginning, I found it beautiful and full of energy. But after half an hour, I started thinking that I needed to see another type of landscape, a reversed angle, or a countershot. Yet there was no countershot, as if nothing existed beyond the scene the curators had selected. It was claustrophobic… So, the problem of d15 is a curating problem, I believe. And because it was not articulated in a complex way but in a one-sided way, all the collectives were just looking similar, working in the same direction. And this accumulation of look-alike experiences created a kind of boredom. In terms of curatorial grammar, there were a lot of misspellings. That’s my main criticism against d15.

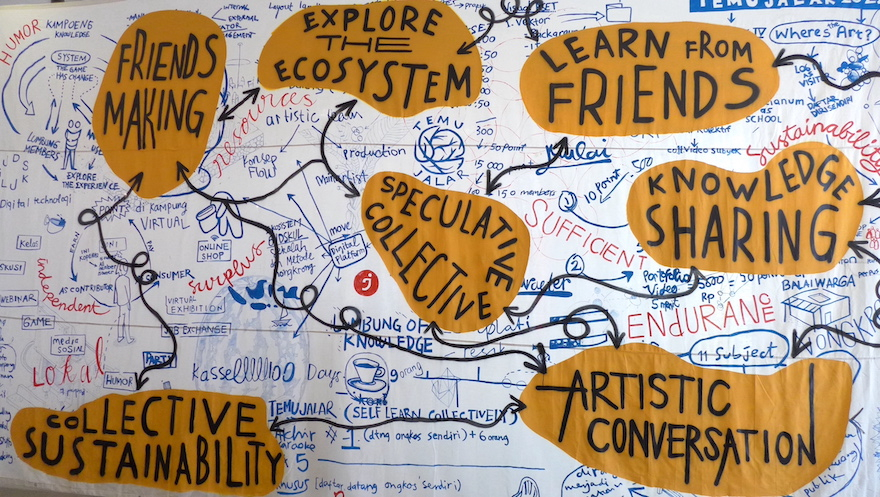

Installation view of Gudskul exhibition at Fridericianum, documenta 15

Did you see

the Okayama Art Summit 2022 curated by Rirkrit Tiravanija?

Bourriaud No. I didn’t.

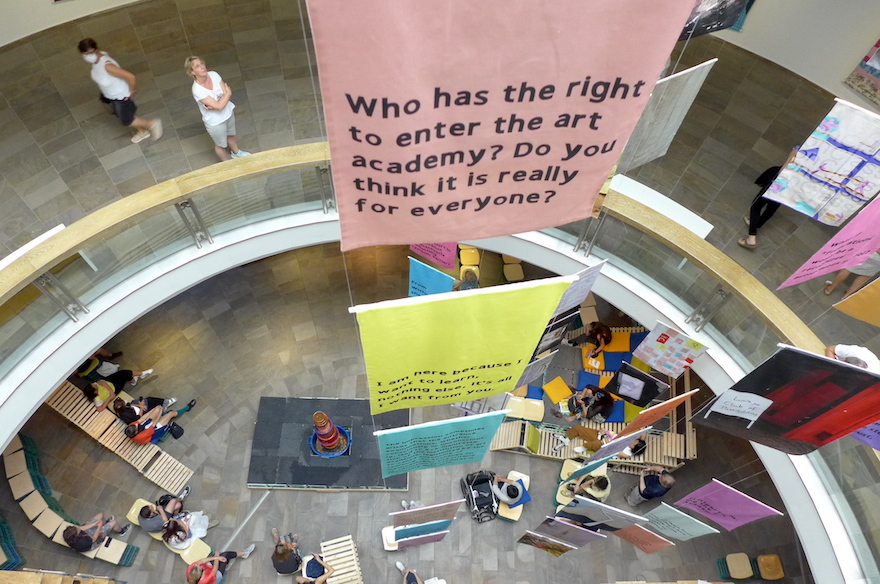

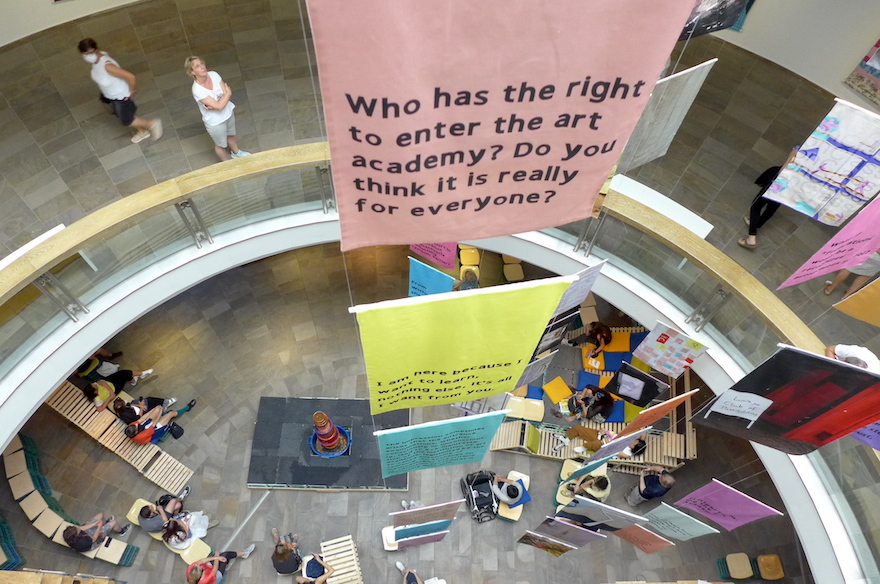

Installation view of *foundationClass*collective exhibition at Fridericianum, d15

After seeing these two festivals, I wrote

a short essay about the difference between the curations of Ruangrupa and Rirkrit.

Bourriaud I guess it’s very different.

Ozaki Yes, very different. On the surface there are some similarities. But in fact, they are totally different. So, I tried to compare the two by the distances from Marcel Duchamp’s famous question which is…

Bourriaud and Ozaki “Peut-on faire des œuvres qui ne soient pas «d’art»?” (“Can one make works which are not works «of art»? “)

Bourriaud It’s very interesting because obviously in d15 you had many participants who are not professional artists, who sometimes don’t fully comprehend the codes of presentation or, how to articulate their ideas, and how to formally organize the rendition of their activities.

Shimabuku Just like children who are shouting.

Installation view of Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts and Culture exhibition at documenta Halle, d15

Installation view of Taring Padi exhibition at Hallenbad Ost, d15

From the nineties we’ve been playing with the margins of art, looking at people who are not artists and including them in exhibitions. That’s a part of what I called “relational art”. But when the margin becomes the center, it becomes unproductive. Anyway, this is a good occasion to think about what curating is. You can make two exhibitions of Mondrian, for example, and one could be very interesting, and the other one very dull. It’s not only a rhetoric, but also a grammar: how to organize space, how to confront artworks one to another? It’s not as innocuous as people may think, it’s also producing a meaning. And depending on what is next to what, you have two different sentences. That’s what you see at d15, it’s a misspelling of art.

Ozaki Or a misediting.

Bourriaud Misediting. That’s a good one!

Asada For example, in Okayama, there are relational artworks and workshops. You can eat Rirkrit‘s curry with local ingredients at an open-air restaurant on the lawn of the former Uchisange primary school, on which you can read the sentence “Do we dream under the same sky.”

Shimabuku Without a question mark.

©2022 Okayama Art Summit Executive committee

And then Rirkrit invited primary school children to make a huge question mark during the opening. A very intriguing move.

Bourriaud There’s more poetry in this than in the whole d15, I think.

OAS2022: Untitled Band (Shun Owada and friends) performing on Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Untitled 2017(Oil Drum Stage), 2017. In the background is Sone’s Amusement Romana, 2002

But on the other hand, there are technically sophisticated artworks like Ryoji Ikeda’s

data.flux――an overwhelming flood of data symbols of every kind, shown on a gigantic LED display next to Okayama Castle. It’s a kind of “technological sublime.” You can’t decode it, you are just overwhelmed, and yet kids are fully absorbed into it when watching. Or in the case of his

spectra shown in the first Aichi Triennale, people just came and danced all night without understanding it ―― or maybe there’s nothing to understand at all. His artworks refuse easy understanding and therefore not “relational,” but involves people in a different way.

Ozaki Exactly. A totally different way.

OAS2022: Ryoji Ikeda, data.flux [LED version], 2021

Courtesy of the artist and TARO NASU

©2022 Okayama Art Summit Executive committee

Photo: Yasushi Ichikawa

Rirkrit arranged those totally different artworks to generate a highly heterogeneous field and embedded it in the City of Okayama. It’s a heterogeneity that seems lacking in d15.

Bourriaud Exactly, heterogeneity. “Where’s the other” and “who am I”. Who am I as the “other” of the exhibition, because at some point you feel easily excluded in this show. It’s the rule system of the exhibition that generates a kind of “other,” which is just the “other in reverse,” actually. And the “other in reverse” is the western white male, let’s say. It’s like the Leninist theory of the bent stick: to straighten the stick it had to be bent in the opposite direction to make…

Asada A balance.

Bourriaud Yes, to make a balance. And that’s the point we are reaching at the moment, which is okay for me. But I think this a priori exclusion is something which is in the end not very productive, I would say. It’s not by creating different lines for the same type of segregation that you reach a better place: it’s by building inclusive spaces, from scratch. I believe this would be more productive. That’s why it’s called inclusions with an “s”, because there are many possible ones for sure.

OAS2022: Shimabuku, Swan Gose to the Sea, 2012&2014

Courtesy of the artist

Collection of Ishikawa Foundation, Okayama, Japan

©2022 Okayama Art Summit Executive committee

Photo: Yasushi Ichikawa

OAS2022: Haegue Yang, Sonic Cosmic RopeーGold Dodecagon Straight Weave, 2022

Courtesy of the artist and Kukje Gallery

With a general contribution from Kukje Gallery

Supported by Okayama Orient Museum

©2022 Okayama Art Summit Executive committee

Photo: Yasushi Ichikawa

So, in Okayama, while Rirkrit and Shimabuku, for example, were doing their own “relational” things, Rirkrit also invited Ikeda’s “high-tech art,” or Yang Haegue’s sublime sound sculpture which was perfectly fitting to the serene space of the Okayama Orient Museum.

Bourriaud That’s right, she was also in the show.

Asada That kind of heterogeneity was interesting, while d15 was rather monotonous though it looked noisy and cacophonous.

Bourriaud d15 is not a cacophony, It’s more of a very rigid system of presentation. It sounds like Penguin Café Orchestra, a band from the eighties mainly composed of people who could not play. So, it was both awful and really inspiring. That was d15: The Penguin Documenta. [laughs]

Asada Penguin Café Orchestra was introduced through Brian Eno’s Obscure label. This label also released Gavin Bryars’ works and his Portsmouth Sinfonia might be another example. Or Takahashi Yuji’s Suigyu Gakudan (Water Buffalo Band). Takahashi was an avant-garde composer and pianist who premiered Iannis Xenakis’ hyper-complicated piece with Pierre Boulez for example, but in the end he abandoned that kind of modernist avant-garde, became Maoist, and started playing like an amateur with other amateurs. When I took part in his stage performance based on Kisaragi Koharu’s script, Takahashi, who is one of the best interpreters of Erik Satie in the world, told me to play Satie’s pieces instead of him, saying it would be more interesting. Of course, it was the most embarrassing experience for me. Nevertheless, it was a wonderful liberation from the already institutionalized avant-garde. But you can’t keep on doing that for decades. Again, it inevitably becomes monotonous.

Bourriaud Monotony is the enemy and “thought” is generated by differences. If there are no differentials, then you have no energy produced. As the differences between cultures are decreasing because of globalization, how can we recreate differences within? So, for me, it could also be differences between individuals, but it’s not the same type of energy that is created by very different cultural spheres.

Asada Gilles Deleuze distinguished singular/universal from particular/general. A and B are different, but this difference is only a part of the alphabet, or of a general classification system. For him, real difference is found between singular points which stick out of such a system. Now, when you started talking about relational art and relational aesthetics, it was about relations of singularities.

Bourriaud Yes, of course.

Asada Like Rirkrit or Shimabuku, they are not particular examples of generic “Relational Art”. Even if Shimabuku speaks Japanese, his Japanese is singular; it’s his own dialect. It’s the same thing for Rirkrit. Of course, I’m not suggesting a return to a kind of personality worship towards artists. But still, Shimabuku is singular, Rirkrit is singular, and that makes them artists. Now as “Relational Art” has become mainstream, some of them have lost their singularities and become generic.

Bourriaud But if you happen to practice a language in a singular way, it is because you also know this language, its grammar and its history. You can’t play with it if you don’t know it. That’s also the issue with d15. What’s the history of the forms that you’re using? If artists don’t have any clue of it, it’s problematic, because you end up repeating what has been done before and you can’t go further. As a result, this kind of spontaneous manipulation of forms then leads to a kind of monotonous situation.

“The constellation goes along, very often, with confusion”

Asada One of our students asked Ozaki-san, “why do we still have to study Duchamp?” Of course we have to study Duchamp. Otherwise you may unknowingly repeat one of his gestures in a much more naïve way. You have to start from the point where everything has been tried by modern and postmodern artists including Duchamp, and make something different, something singular. Cultural amnesia, on the other hand, inevitably leads you to a monotonous repetition.

Ozaki Unfortunately, with the Japanese art lovers, there has been almost no word on Duchamp after the deaths of him and his experts. Before his death, there were at least two very close Japanese friends/critics Takiguchi Shuzo and Tono Yoshiaki who were quite keen about introducing what Duchamp had said, did, and what the international critics wrote about him almost in real time. So it was okay in the sixties, even after Duchamp’s death in 1968, until the opening of the Pompidou Centre with the inaugural exhibition of Duchamp in 1977. But after the passing of Takiguchi in 1979 and the hospitalization of Tono due to a brain stroke in 1990, there have been significantly less discussions and publications about Duchamp. The Japanese version of

Duchamp du signe edited by Michel Sanouillet and Paul Matisse was published in 1995, Calvin Tomkins’

Duchamp: A Biography in 2003 and the exhibition

Mirrorical Returns: Marcel Duchamp and the 20th Century Art curated by Hirayoshi Yukihiro was held in 2004. That’s all. Nothing more after that, except a few exhibitions held on the 100th anniversary year of

Fountain in 2017.

Bourriaud I just saw

the Frankfurt’s exhibition.

Ozaki I saw it, too.

Asada But even though Ozaki-san is right about the temporary lack of interest in Duchamp, we in Japan have always been conscious of the history of modern art, postmodern art, et cetera. The big problem now in Asia, especially in China, is the almost total lack of historical perspective. Everything comes at once ―― premodern, modern, postmodern, everything. You can choose what you want, you can do whatever you want. That does not mean you can be free because when direction is lost, moving forward becomes very difficult.

Bourriaud The direction of time has changed in the last 30 years for me. Before we were all infested with this idea of progress, implying that time was going from one point to another point, like an arrow. Now we are moving to something diametrically opposed, which is the idea of constellations. Considering that everything is available now and from everywhere, from every time.

Shimabuku But don’t you think that everything is a kind of established style?

Bourriaud [Not responding to the question] What would be the equivalent? The constellation, the visible cosmos. If you look at the stars, you have it. You have stars which disappeared million years ago but still glow. And you have different types of periods of time in the same image. That’s more or less the metaphor of our culture, based on the internet which is a constellation. But in the end, it comes down to one type of restaurant. The one where you could actually sit down and ask for either a pizza or a burger or Kaiseki cuisine or…

Asada Chinese, Italian…

Bourriaud Yes. It doesn’t make sense! It doesn’t make sense. Those are the limits of this constellation system.

Asada Your metaphor of constellations reminds me of Walter Benjamin.

Bourriaud Yes. Of course.

Asada Stars in a constellation are not on the same surface. Their lights come from different distances, and consequently they have different ages.

Bourriaud But now we see it in a negative way, at least, not something which is productive and idea-generating.

Asada In a way, the constellation has lost spatial and temporal depths and has become flat.

Bourriaud The constellation goes along, very often, with confusion.

Another very important point about Benjamin; he indexed the notion of the artwork with the notion of aura. And the aura comes, as he writes, from the unique apparition of something faraway. We don’t have this anymore. I try to describe contemporary space-time as structured by the Larsen effect, or feedback effect, if you prefer, which happens in music when two emissions are too close to one another. In other words, the global space is diminishing and narrowing. For example, wild animals don’t have any space anymore to live. We are getting closer and closer to them. Everything is getting close and closer. This is the source of what I call the visual Larsen effect which creates strident sounds and noises. This has become frequent in contemporary art and in our visual culture. A Lack of distance and the disappearing of distances.

Asada Yes, that’s problematic also because they are not really close to each other, while they look close to each other on their tiny phone displays. They may be in totally different contexts, but there’s no context in those images simply juxtaposed with each other.

“Connecticut or Connect-I-Cut”

Bourriaud But if we go back to Duchamp, one of the strong points of his vision was also coming from the idea of distance. He was a Frenchman but living in New York. This was of tremendous importance to him and was the basis for understanding the two worlds of ‘Europe and America’. And this was only possible with distance.

Ozaki Yes.

Bourriaud If you are just the nose on an image, you see nothing, especially me, cause I’m getting long-sighted… [ laughs] Distance allows us to create new spaces for thinking. Without the art of distance, for example, there’s no possible importation. And Duchamp imported many things in art from faraway. If you don’t have it, if everything is available all the time, how can you create, dig a new space for thinking? This is an essential question that we could ask for ourselves today. The first artist might have been also someone who was coming from some other place. That’s how traders were actually despised of in western culture at the very beginning. Because they were coming from far, from abroad. They were the unknowns, the strangers, the aliens.

Ozaki They were not able to meet local people face-to-face, so they placed their treasures on the ground or on the beach.

Asada Then they would wait and see what would be brought in exchange to their treasures as an equivalent. This was the so-called silent trade.

Bourriaud And what was their job? It was taking something from one place and bringing it to another place. That’s what the traders in the original Neolithic societies were like. What did Duchamp do? He took one element from one place, at the BHV, and displaced it at the gallery: it’s exactly the same thing. But you need to come from afar, you need distance. Otherwise, there’s no magic, no benefit and no interest. Because receiving something that already exists is neither interesting nor beneficial.

Tsuru-Devaux It’s related also with what you were saying yesterday at the Art Collaboration Kyoto, about appropriation, maybe.

Bourriaud Yes.

Tsuru-Devaux You were saying that there is no art or culture without appropriation.

Bourriaud Yes. I also mentioned that appropriation is not the right term. Appropriation means property, whereas my vision of culture is based on “use”. We use things that came from somewhere else, but we never own them.

Ozaki I would like to pose the last question. What do you think about solitude? Nowadays a lot of people seem to consider meeting or connecting very important. But on the other hand, artists like Duchamp preferred to be alone. I think solitude is indispensable for any artist who desires to create something.

Bourriaud I don’t think it’s contradictory with relations, I think it’s complementary in a way. There’s a quotation that comes to my mind from Georges Bataille, which is like… I’d say better in French, but, uh… More or less it’s impossible for someone who’s alone to think and reflect on the world. Because you’re self-centered as long as you’re alone. When you are with someone, when you get into dialogue, the center moves, and then you can see the world and understand it. So, it’s impossible to think about the world by yourself. But at the same time, you need to take distance and I think taking distance does not necessarily mean being alone. You can take distance and be with others. That’s the good loneliness I tend to prefer.

Asada Gilles Deleuze notoriously said: “Philosophy has nothing to do with communication. It is creation.” But it doesn’t mean that he’s alone.

Bourriaud Yes. I am totally Deleuzian on this.

Asada Yes, but he was not alone. He even wrote books with Félix Guattari. I think their relation ― and their concept of relation ― is symbolized by a word in

L’Anti-Oedipe: Connecticut or Connect-I-Cut. Every time I am connected, I know I have to cut off the connection, but that means I am already connected, and vice versa.

Bourriaud Yes, it’s also continuity / discontinuity.

Asada So, it’s time to end our conversation and go to the restaurant. Thank you very much.

Nicolas Bourriaud, born in 1965, is a curator and writer. He is the founder of

Radicants. Bourriaud was the director of Montpellier Contemporain (MoCo), an institution he created, gathering the La Panacée art centre, the Ecole Supérieure des Beaux-Arts and the MoCo Museum, from 2016 to 2021. He was the director of the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris from 2011 to 2015. From 2010 to 2011, he headed the studies department at the Ministry of Culture in France. He was Gulbenkian Curator for Contemporary Art at Tate Britain in London from 2007 to 2010 and founder advisor for the Victor Pinchuk Foundation in Kyiv. He also founded and co-directed the Palais de Tokyo, Paris between 1999 and 2006.

Bourriaud’s recent exhibitions include

PLANET B. Climate change and the new sublime, Palazzo Bollani, Venice (2022);

Crash Test, La Panacée (2018);

Back to Mulholland Drive, La Panacée (2017);

Wirikuta, MECA Aguascalientes, Mexico (2016);

The Great Acceleration. Art in the Anthropocene, Taipei Biennial (2014);

The Angel of History, Palais des Beaux-Arts (2013);

Monodrome, Athens Biennial (2011) and

Altermodern, Tate Triennial, London (2009). Nicolas Bourriaud was also in the curatorial team of the first and second Moscow Biennials in 2005 and 2007. His selected books are

The Exform (Verso, 2016);

Radicant (Sternberg Press, 2009);

Postproduction (Lukas & Sternberg, 2002);

Formes de vie: L’art moderne et l’invention de soi (Denoel, 1999) and

Relational Aesthetics (Presses du réel, 1998).

Asada Akira (Critic / Director, ICA Kyoto)

Ozaki Tetsuya (Journalist / Realkyoto Forum Editor-in-Chief, ICA Kyoto)

Shimabuku (Artist)

Emilie Tsuru-Devaux (Art historian / Program Officer, ICA Kyoto)

This conversation took place on November 20, 2023 in Kyoto.

Portraits: Shimabuku (conversation) and Ozaki Tetsuya (talk at ACK)

Installation views of the exhibitions: Ozaki Tetsuya, Yoshida Hiroko and Ichikawa Yasushi

Transcription: Emilie Tsuru-Devaux

English translation of the lead: Ozaki Tetsuya

English proofreading: Huang Ellan