Memorial Symposium

Ryuichi Sakamoto and Kyoto (Part 1)

Akira Asada, Shiro Takatani, Lucille Reyboz, Yusuke Nakanishi, Akeo Okada, Kazuko Okada, Kohei Nawa, Marihiko Hara, Ko Kado and Oussouby Sacko

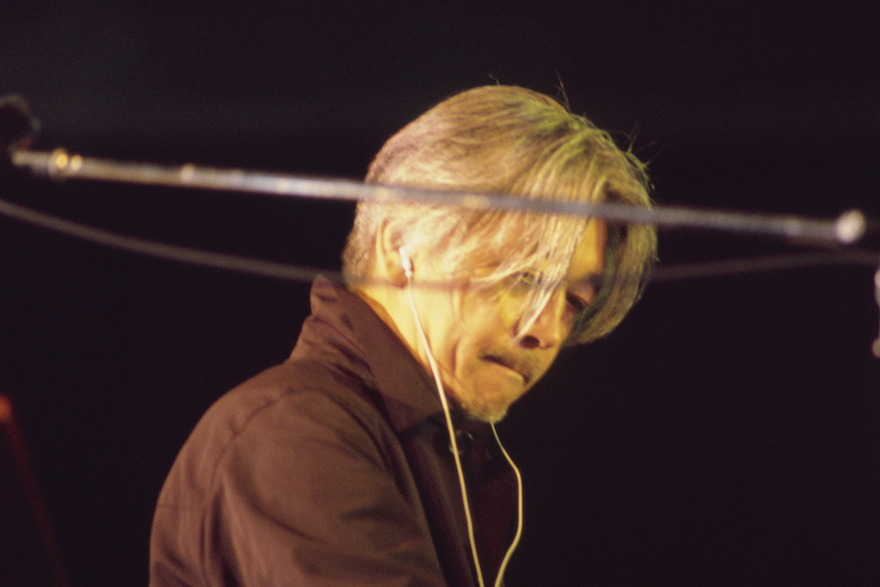

Photo by Shiro Takatani

Shiro Takatani (Artist)

Guest commentators (in order of appearance): Lucille Reyboz (Co-founder/Co-director, KYOTOGRAPHIE International Photography Festival)

Yusuke Nakanishi (Co-founder/Co-director, KYOTOGRAPHIE International Photography Festival)

Akeo Okada (Musicologist/Professor, Institute for Research in Humanities, Kyoto University)

Kazuko Okada (Composer/Professor, Kyoto City University of Arts)

Kohei Nawa (Sculptor/Professor, Kyoto University of the Arts)

Marihiko Hara (Musician)

Ko Kado (Karakami Craftsperson/Owner, Kamisoe Shop)

Oussouby Sacko (Spatial Anthropologist/Director, Center for Africa-Asia Contemporary Studies, Kyoto Seika University)

Moderator: Tetsuya Ozaki (Editor-in-chief, REALKYOTO FORUM, ICA Kyoto/Professor, Kyoto University of the Arts)

Editing and Composition: REALKYOTO FORUM

——————————–

Moderator (Ozaki): As we are all aware, on March 28 of this year [2023], Ryuichi Sakamoto passed away. At just 71, one might say his death was far too early. Not surprisingly, considering his extensive and boundary-crossing career, memorial events continue to take place worldwide. Interestingly, Sakamoto also had a substantial connection with Kyoto, and today, we have the privilege of welcoming two Kyoto-based speakers who were intimately acquainted with Sakamoto-san: critic and ICA Kyoto Director, Akira Asada, and artist Shiro Takatani, who will share their insights into Sakamoto’s work. We also welcome eight individuals who, in various ways, had connections with Sakamoto-san here in Kyoto. Later on, we’ll ask them to join us as guest commentators to offer their reflections on the multifarious activities of this one-of-a-kind musician.

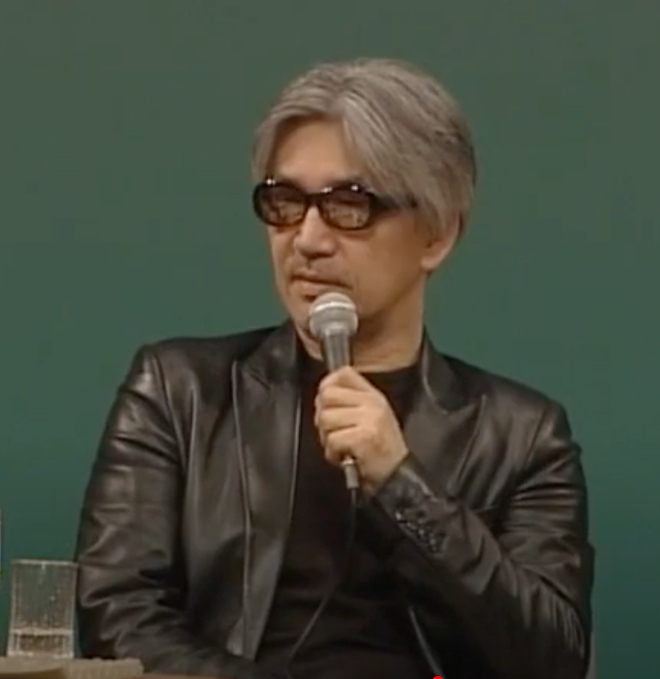

Shiro Takatani (left) and Akira Asada

Photo by Kenryou Gu

Around the time Asada first met Sakamoto, Shiro Takatani co-founded the artist collective Dumb Type in 1984 with associates from Kyoto City University of Arts. Along with his Dumb Type activities, Takatani has pursued a solo career in photography, film, and performance. This has included collaborating extensively with Sakamoto in ways likely to be illuminated in today’s conversation. Last year (2022), Dumb Type represented Japan at the Venice Biennale, pinnacle of contemporary art festivals. The composition of Dumb Type’s members is fluid, and during the Biennale period Sakamoto was also part of the group.

To begin our discussion, I’d like to ask Asada-san to share with us his perspective on the achievements and significance of the artist Ryuichi Sakamoto. – From Classical to Modern and Postmodern Asada: As Ozaki-san mentioned, since the death of Ryuichi Sakamoto a multitude of people across borders and genres have been expressing their condolences, and offering their memories of him. Due to my long association with Sakamoto, stretching back to 1984, I thought I knew a lot about him, but I’ve come to realize there are many aspects of him that I wasn’t aware of. The depth of his connection with Kyoto may be one. I suspect our discussion today will help us to paint a broader picture of this remarkable man.

How to describe the presence that was Ryuichi Sakamoto? While each of you may have your own image of him, let me provide some information that serves as a common starting point. In the context of Japanese mass media reporting especially, the image of Ryuichi Sakamoto usually begins with the band Yellow Magic Orchestra (YMO), formed in 1978. However, to truly gain a complete picture of Sakamoto, we need to trace back a bit further.

Ryuichi Sakamoto was born in 1952. His father was a literary editor who worked with legendary writers such as Yukio Mishima and Yutaka Haniya, and his mother was involved in hat design. So he was raised in a household steeped in the post-war cultural zeitgeist. Familiar with French music such as that of Debussy, after experimenting with the avant-garde he eventually transitioned to techno-pop. However, prior to all of this, his musical knowledge was rooted in classical music of German and Austrian origin, most prominently that of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, a.k.a. “the 3 Bs.” He not only played their music on the piano but also studied assiduously the analysis of their compositions, and their composition techniques. Even as an adult Sakamoto continued to love learning and, under the title “Schola,” produced CD books and a TV series in an effort to study music anew, covering everything from classical to folk and pop. During this time, I had the opportunity to study alongside him to a considerable extent. Even when selecting recommended performances for the series, he chose true orthodox figures of the pre-war era like the conductor Furtwängler and singer Wunderlich, rather than post-war popularized figures like Karajan or Fischer-Dieskau. For Debussy’s string quartet, instead of recordings by ensembles like the LaSalle Quartet, he chose recordings by the Budapest String Quartet that he first listened to as a child. In this sense it is essential to emphasize that in terms of both cultivation and tastes, his musical foundations were literally classical.

As an extension of this, Sakamoto, awakened to music through Debussy, closely followed the development of modern music by figures such as Schoenberg in the German-speaking world, Debussy in France, and Stravinsky in Russia, along with Bartók in Hungary. After the war, contemporary music was developed by avant-garde pioneers such as Messiaen, followed by Boulez, Stockhausen, Nono, and Cage. Japan had it own pioneer in the person of Toru Takemitsu, who starting from Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop) performed the most worldwide of any Japanese avant-garde composer, also becoming widely recognized through film and television.

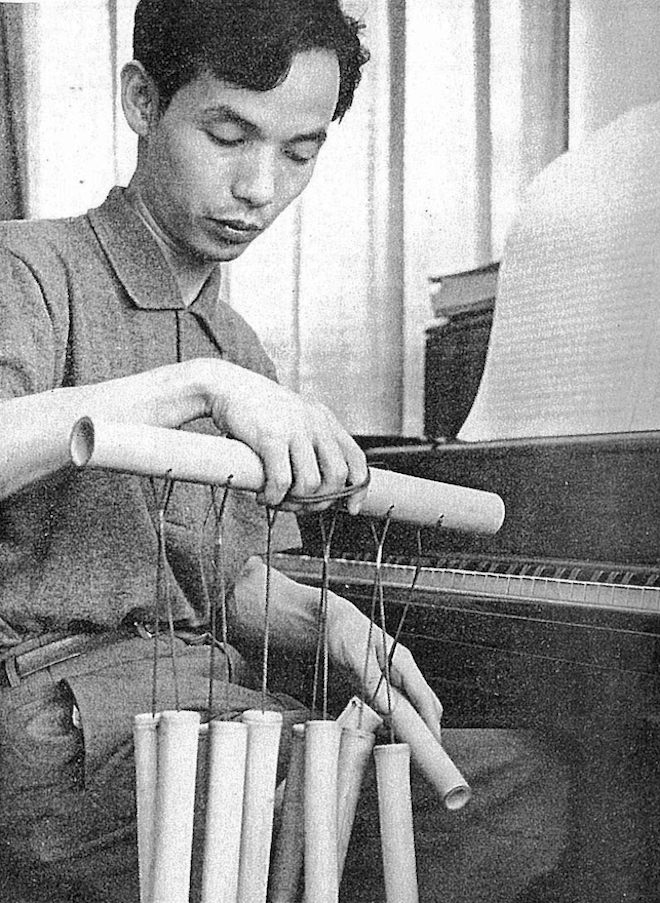

Toru Takemitsu in Geijutsu Shincho magazine, July 1961

Steel Pavilion, Expo ’70, Osaka

Space Theatre Program of Steel Pavilion at Expo ’70 CD, 2004

Iannis Xenakis, 1975

CC-BY-2.5

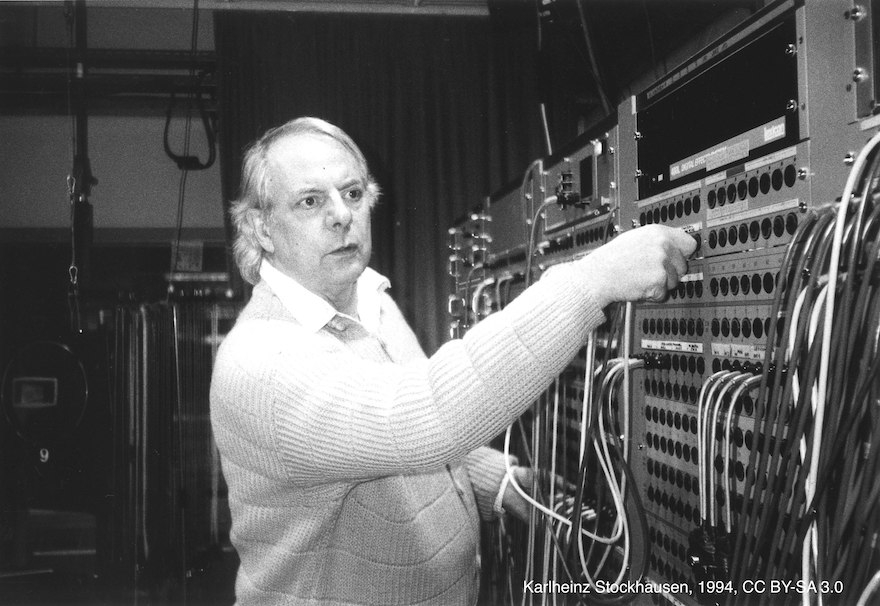

Karlheinz Stockhausen, 1994

CC BY-SA 3.0

Stockhausen’s Spherical Concert Hall, German Pavilion, Expo ’70, Osaka

© Karl-Heinz Stockhausen, Fritz Bornemann

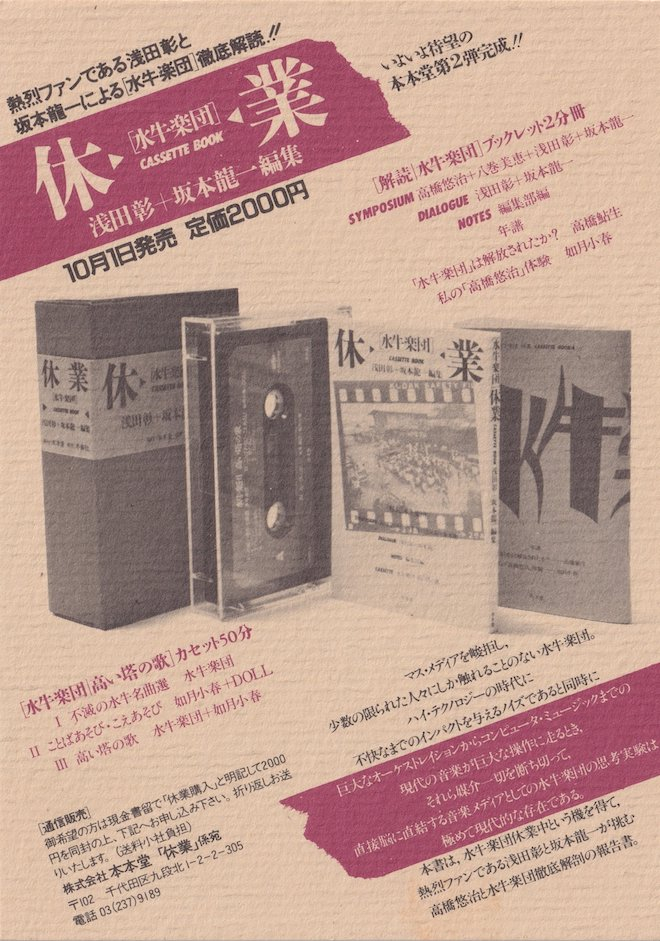

Suigyu Gakudan (Water Buffalo Orchestra), Kyugyo (Vacation), 1984

Cornelius Cardew, Stockhausen Serves Imperialism, 1974

Ryuichi Sakamoto, surprisingly, attended concerts by Yuji Takahashi, in his early teens. He might have admired Takemitsu and Takahashi. However, once Takahashi’s generation had pushed the avant-garde to its limits, Sakamoto couldn’t simply follow the same path. Musicians like Holger Czukay who studied under Stockhausen in Germany, found themselves in a similar situation. In response they spun out into rock, forming a band called Can. Others close to Can formed Kraftwerk. Kraftwerk used electronic sound, but didn’t delve into complex and challenging avant-garde music like Stockhausen, instead preferring the endless mechanical repetition of very straightforward, catchy phrases. Their music was completely opposite to that of the avant-garde, which had discarded predetermined rhythms such as the diatonic scale and the likes of tonic-dominant harmony and the fixed rhythms of 4/4 and 3/4, in its pursuit of radicalization and complexity. It became known as techno, and YMO’s music, influenced by it, came to be called techno-pop.

Rock was also popular in Germany of course, but people in the English-speaking world would often mockingly say that rock could only be in English, and belittle Germans as being stiff know-it-alls with zero groove. Kraftwerk could be seen as turning this stereotype on its head. They may well have thought, “Oh, yeah, that’s right. We’re robots, so we might as well make mechanical repetitive music.” As this approach became more widespread, an animalistic groove began to emerge, exemplified by James Brown, and music that could be described as a fusion of Kraftwerk and Brown came to be referred to as techno once again.

Can Taizen, edited/supervised by Shinya Matsuyama, 2020

Kraftwerk, 1976

Photo by Ueli Frey. CC BY-SA 3.0

Ryuichi Sakamoto, Thousand Knives, 1978

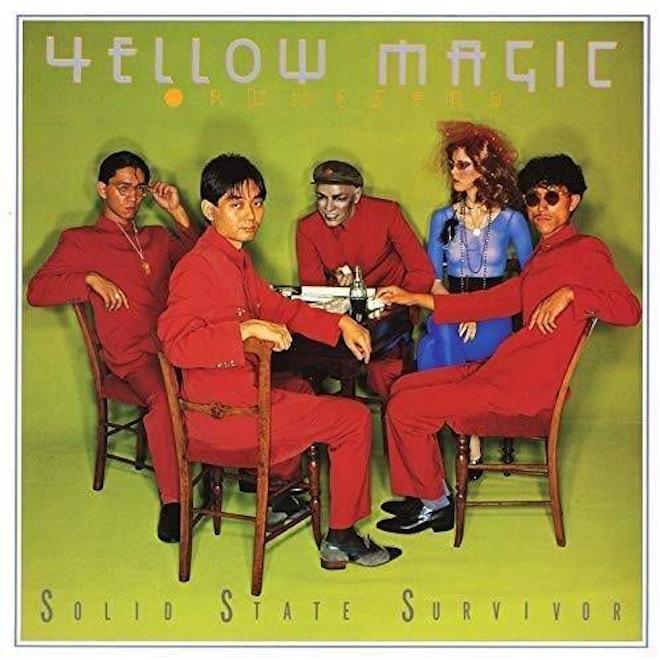

Yellow Magic Orchestra, Solid State Survivor, 1979

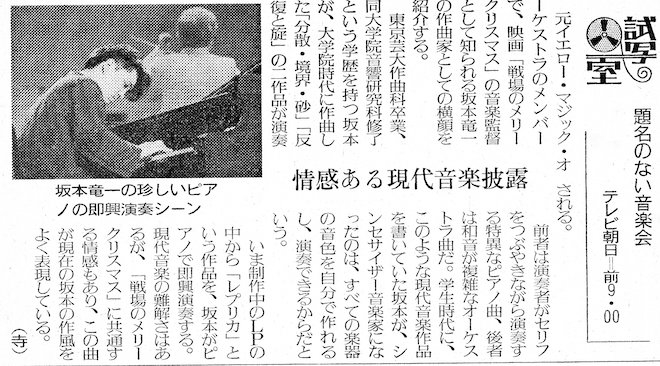

Newspaper article about “Daimei no nai ongakukai” [Untitled Concert], 1984

Ryuichi Sakamoto, B-2 UNIT, 1980

Ryuichi Sakamoto, Illustrated Musical Encyclopedia, 1984

Concept book of Illustrated Musical Encyclopedia, 1985

Poster for Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence

On the other hand, as mentioned earlier, 1983 was the year I published my first book, Kozo to Chikara (Structure and Power). It was also the year Shinichi Nakazawa released Chibetto no Mootsuaruto (Mozart in Tibet). This period marked the beginning of the popularity of structuralism/post-structuralism, in other words, the onset of postmodern thought. In this intellectual landscape, Ryuichi Sakamoto and I drew closer, as did Haruomi Hosono and Shinichi Nakazawa, though Sakamoto and Nakazawa maintained a long friendship, later embarking on a journey to explore Jomon culture together. In the architectural realm too, the late Arata Isozaki, who passed away late last year, completed the Tsukuba Center Building, a paradigm of postmodern architecture, in 1983. This era witnessed a postmodern boom in Japan, setting the stage for my first encounter with Ryuichi Sakamoto in 1984.

During this period, the Seibu Group (later the Sezon Group) served as a major driving force in postmodern culture. For example, this was when people were talking about the advertising copy of Shigesato Itoi. On the art scene, there were exhibitions by Joseph Beuys at the Seibu Department Store’s art museum, and Nam June Paik (a Fluxus artist and one of the founders of video art) at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum and Galerie Watari (now Watari-um). Beuys and Paik performed at the Sogetsu Kaikan, a venue associated with avant-garde music in Japan. Paik was invited by Ryuichi Sakamoto to participate in performances that brought together not only avant-garde musicians such as Yuji Takahashi, but pop practitioners like Sakamoto, Haruomi Hosono and Hajime Tachibana. This collaboration also exemplifies the transition from modernist avant-garde to the hybrid experimentation of postmodernism. In the same year, 1984, Laurie Anderson made her debut in Japan, holding performances in Kyoto. This was also the year that students from Kyoto City University of Arts including Shiro Takatani founded the multimedia performance group Dumb Type. Takatani: We started around the time of Illustrated Musical Encyclopedia. Back then it was mainly Teiji Furuhashi and Toru Yamanaka creating music, and listening to their works again, it is obvious they were heavily influenced by Sakamoto-san’s album. Everyone seems to have been sharing the sound and rhythm of the synthesizers that were becoming popular during that era, to the extent that it might be mistaken for copying. I have a feeling we might have been creating performances inspired by minimal music, by the likes of figures such as Steve Reich. Asada: The role of minimal music was indeed substantial, with figures like John Cage pushing the boundaries of music to the point of a tabula rasa with his work 4’33” where the pianist remains silent for that specific duration. Following this, Steve Reich, Philip Glass, La Monte Young, and Terry Riley, who now resides in Japan, started minimal music by mechanically repeating simple musical phrases to create alternative orders. In the visual arts, having reached the extremes of a white or all-black canvas (as seen in the works of Rauschenberg, who revisited the achievements of avant-garde art), Minimal Art had emerged that featured small forms or mechanically arranged elements like sticks or boxes, and this was essentially the musical version of that. However, while Minimal Art is considered a late-stage phenomenon in art history’s modernist phase, figures like Reich started incorporating real-world sounds by looping tape recordings, and works like the famous Different Trains suggest a more apt description would be postmodern. The sight of Reich and Kraftwerk sharing the stage at music festivals was certainly a postmodern phenomenon.

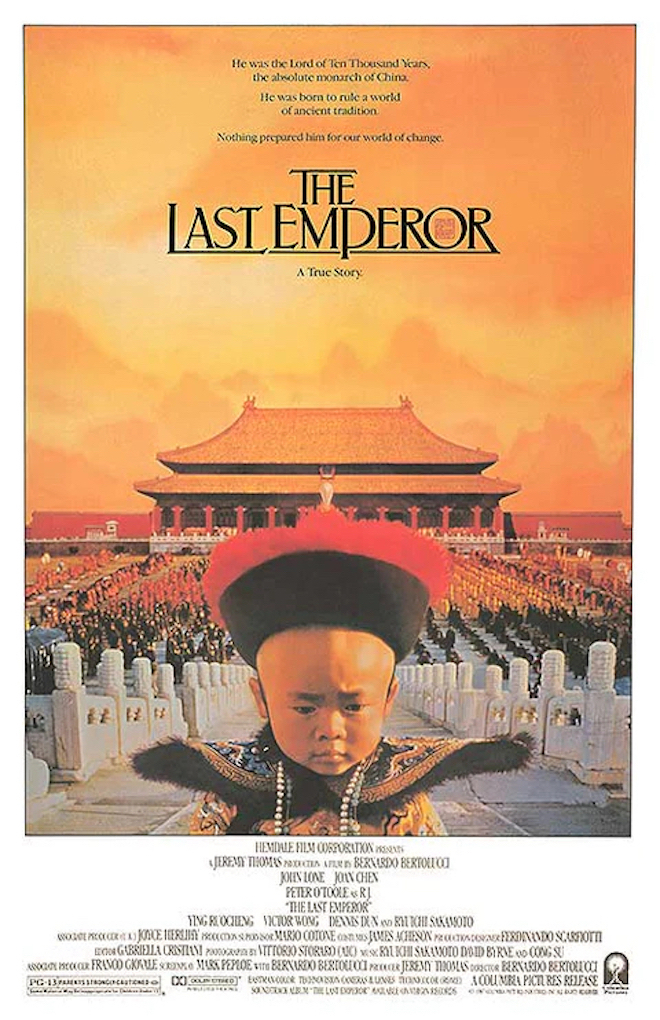

Incidentally the term minimal music was first used by Michael Nyman in a review of Cornelius Cardew, mentioned earlier. Nyman gained prominence through his album Decay Music (1976), one of Brian Eno’s Obscure Record issues. Eno went on to create what is now known as ambient music, and in his early days was a star in the rock group Roxy Music, broadly speaking playing a role akin to that of Ryuichi Sakamoto. – From Contemporary Music to Film Music Asada: Ryuichi Sakamoto delved into film music with Nagisa Oshima’s Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence in 1983. Following this collaboration with Oshima, he went on to win the Academy Award for Best Original Score for Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor in 1987. Sakamoto and Bertolucci were in a way in similar positions. Bertolucci began his career in filmmaking as assistant director on Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Accattone (1961). However, he was (as was Pasolini) most fascinated by Jean-Luc Godard, at the forefront of the French New Wave in the 1960s. After becoming politically radicalized and experiencing setbacks during his trip to Palestine, Godard temporarily disappeared from the commercial cinema scene. The question for Bertolucci was whether spectacle in cinema was still possible after Godard’s dismantling. This became his inquiry, and he progressed from works like The Conformist (1971) through to The Last Emperor.

Poster for The Last Emperor

Takatani: Sakamoto-san took quite good photos , but mentioned that he did not shoot film himself. Nonetheless, he had a deep interest in and knowledge of camera work. His involvement in The Last Emperor, where Storaro’s cinematography and Bertolucci’s direction align, seemed almost destined.

Asada: Sakamoto’s ability to synchronize music precisely with the moment the camera starts moving or when a smiling face clouds over slightly was exceptional. He mentioned working on a microsecond basis, aligning the music precisely with a single frame. However, directors in film, being typically chaotic, might say, “I changed the edit later,” leaving Sakamoto to exclaim, “Oops!” (laugh).

Moderator: We have an unusual video to share; let’s take a look. [Screening of the video “Field Work”] Asada: “Field Work” (1985) is a promotional video for the song composed by Ryuichi Sakamoto and performed by Thomas Dolby. Dolby served as the director and lead actor, with Sakamoto also making an appearance. Sakamoto mentioned that the video didn’t turn out exactly as he envisioned, and there may have been some directorial disagreement with Dolby. What’s interesting is that Sakamoto played the role of a Japanese sergeant who, having hidden on Iwo Jima after the war, is discovered and now lives in New York as an elderly man. The character is reminiscent of individuals like Shoichi Yokoi or Hiroo Onoda (more the latter), who remained in hiding without knowing about, or perhaps acknowledging, Japan’s defeat. In Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence Sakamoto portrayed a Japanese POW camp commandant. “Field Work” is his attempt to confront the memories of war in line with Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, drawing inspiration from pre-war expressionist cinema, with the exaggerated expressions of that era, also akin to Merry Christmas. In his later years, Sakamoto engaged in his own fieldwork with natural sounds, creating music directly from nature, but in this context, “field work” represents historical fieldwork. And note that in The Last Emperor he portrayed Masahiko Amakasu, head of the Manchurian Film Association in Manchukuo, manipulating Puyi, the last emperor of the Qing dynasty and also emperor of the puppet state, in the manner of a movie director.

Moderator: Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence was made in 1983, The Last Emperor in 1987, and “Field Work” in 1985, placing it between these two films.

Asada: When asked by Haruomi Hosono in YMO, Sakamoto agreed to write “catchy, saleable songs,” and went on to compose tracks like “Behind the Mask.” Michael Jackson of all people was enthralled by “Behind the Mask,” and it was supposed to be featured on his immensely successful album Thriller, but due to copyright issues, this did not happen. The fascinating aspect of YMO is how they seamlessly transitioned from avant-garde music, relatable only a few, to the level of Michael Jackson.

Similarly, when invited by Bernardo Bertolucci to help shoot a spectacular film even after Jean-Luc Godard had deconstructed cinema, Sakamoto managed to pen a majestic score befitting Vittorio Storaro’s magnificent visuals.

Later on, influenced by the bossa nova of Brazil’s Antonio Carlos Jobim, and Argentina’s tango, Sakamoto performed his versions as part of a trio, captivating Mexico’s Iñárritu with “Bibo no Aozora” (“Beautiful Blue Sky”). He truly did have the capability to do anything.

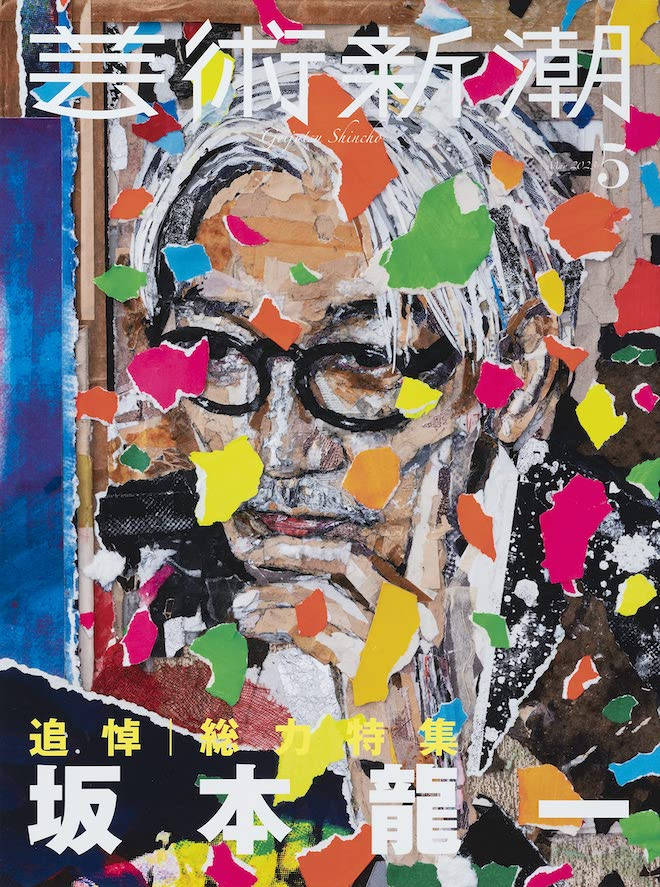

Geijutsu Shincho magazine, May 2023

Firstly, during the era of Kraftwerk and YMO, I actually felt that Kraftwerk’s total cynicism, where they fully became robots and mechanically repeated simple phrases, made them cooler than YMO, who were like half-human, half-robots, and therefore somewhat half-baked. Fortunately or unfortunately, YMO had an incredibly skilled bassist and a drummer, creating a groove that made listeners dance. Although Ryuichi Sakamoto wore the mask of an emotionless mechanical being, underneath that mask he was actually having fun. Especially during live performances, you could see YMO with Akiko Yano in the background energetically dancing as they performed. So YMO, despite being considered a postmodern musical machine, was all too human, and actually, musically danceable. The same can be said for his film music, tango, and other types of music.

In reality, Ryuichi Sakamoto just loved music, and more specifically, sound. The term “amateur” comes from the French word meaning someone who loves. Though styling himself as a professional studio musician, able to handle any music requested, Sakamoto actually loved every kind of music and, in fact, sound itself. To call him a cynical postmodern music machine would be mistaken. For the sake of the publication, this point was excessively simplified, so I wanted to amend it here. The postmodern music machine, and the human who listens to the world’s sounds with his entire body and transforms them into his own music, are the starting and ending points of his career as a musician. In fact, it might be more accurate to say that the face of the amateur initially hidden behind the mask, gradually came to the surface.

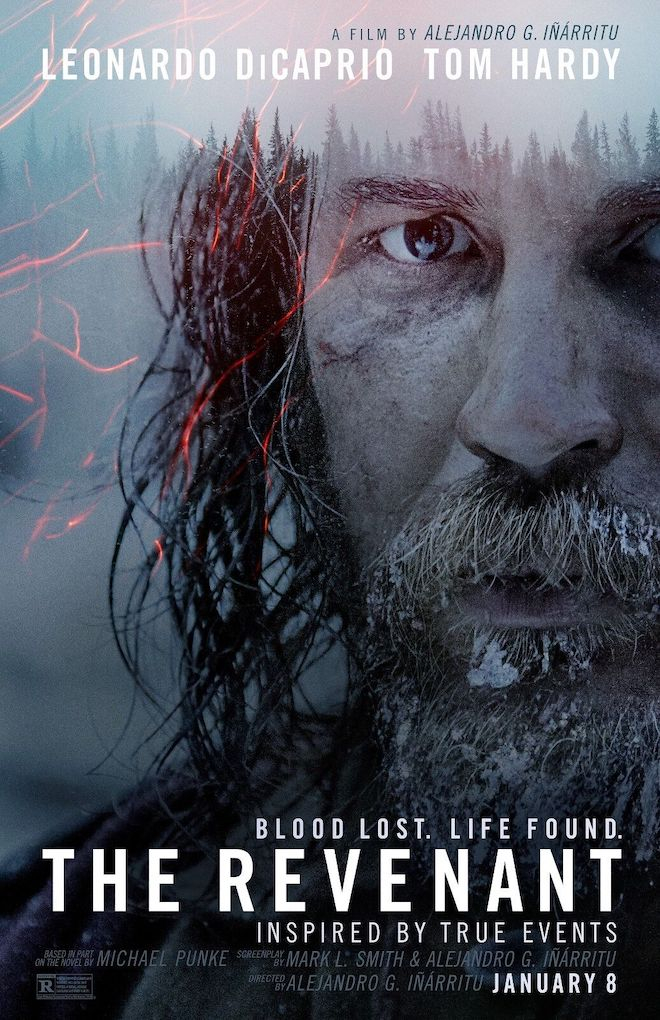

Moderator: In 2015, Ryuichi Sakamoto was in charge of the music for Alejandro González Iñárritu’s The Revenant.

Poster for The Revenant.

Set in a wintry northern land, the film features Leonardo DiCaprio as the protagonist. He fathers a son with a Native American, then referred to as an Indian, but the son is killed by savage white men. The story revolves around the protagonist repeatedly almost dying but returning to this world to seek revenge. The narrative is intense, and the harsh filming conditions led to DiCaprio suffering frostbite multiple times. He also won his first Academy Award for Best Actor. DiCaprio, who had previously portrayed a nefarious and brutally unjust slave owner who proclaimed the biological inferiority of black people in Tarantino’s Django Unchained (reminiscent of Shelly’s Prometheus Unbound), here takes on a role distinct from other white characters, portraying someone close to nature and the Native American way of life. This main character is attacked by a bear, sustaining serious injuries. His occasional utterances become barely audible, yet against this backdrop, there is music that evokes the opening of Mahler’s Symphony No. 9. The sheer scale of the music that seems to mimic the gasping of someone near death creates what feels like a faithful reproduction of the sounds of the majestic northern landscape. This work can be seen as the beginning of Ryuichi Sakamoto’s later style, breaking through to the point of not structuring music by organizing sounds (musical tones) excluding noise, but rather converting the echoes of nature and the very cries of the world into music. This music and sound design seemed to be beyond the understanding of the Academy, with its persistent devotion to theme tunes, and the Academy Award for Best Original Score in that year went to Morricone for Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight. A questionable decision, because The Hateful Eight could hardly be described as an outstanding example of Tarantino’s work, nor the music exceptional in terms of Morricone’s compositions. I believe that The Revenant is far superior. Nonetheless, the Oscars are merely an industry award, so there’s no real need to dwell on this. – Encounter with Shiro Takatani

Ryuichi Sakamoto, async, 2017

Ryuichi Sakamoto, 12, 2023

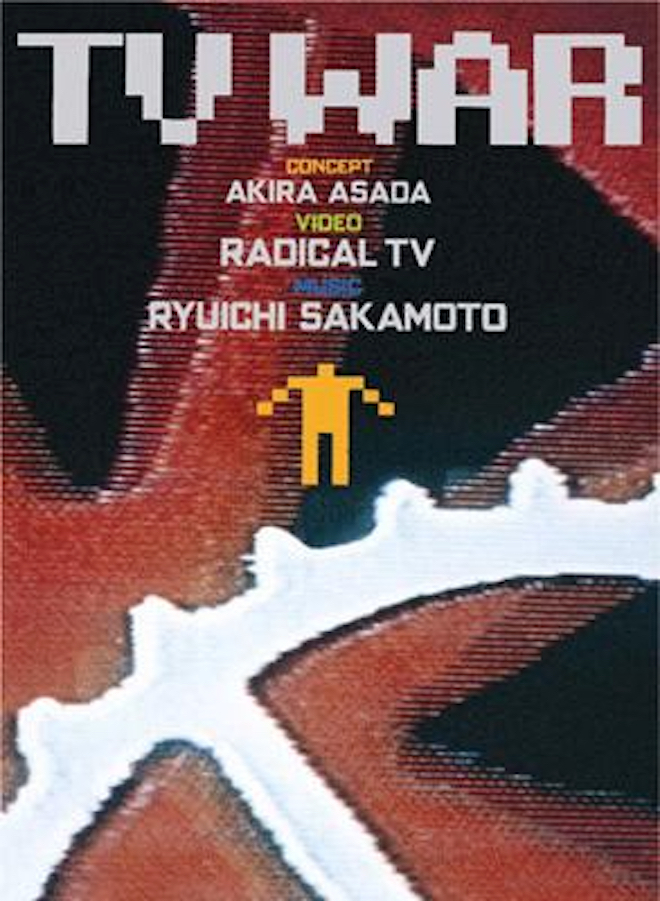

Akira Asada + Radical TV + Ryuichi Sakamoto, “TV War” DVD, 1985/2005

Ryuichi Sakamoto, LIFE a ryuichi sakamoto opera 1999, 1999

Teiji Furuhashi. Photo by Ryuichi Sakamoto (Original photo by Shiro Takatani)

Courtesy Kab Inc./ KAB America Inc.

After this, Teiji Furuhashi had stayed in New York with an ACC grant, and when I visited New York, I met with him and took him to meet HIV/AIDS activist Douglas Crimp (also known as a critic of postmodern art) to help prepare for an event related to the World AIDS Conference in Yokohama. During that time, he told me that he enjoyed watching CAVE by Steve Reich and Beryl Korot at the Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM), a venue known for the performances of artists like Bob Wilson and Pina Bausch. Although the live performance had already finished, there was an interesting video installation version being showcased at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). It was a soaring yet painstakingly-constructed piece of documentary music video theater, a sort of expanded version of Different Trains that incorporates recorded testimonies from a train conductor who shuttled between the East and West Coasts where Reich’s divorced parents lived during his childhood, Jewish people transported by train from Western Europe to Polish extermination camps during the same period, and post-war Americans. It also explored the theme of the cave in Hebron where Abraham and his family were buried, by collaging the words of Jewish people in Israel, Arab people in Palestine, and Americans, tracing the intonation of their narratives through musical instruments. As a result, I was introduced to Beryl Korot by Barbara London, a curator who had been dealing with video art at MoMA. Being one of the organizers, I decided to invite Korot to Japan for a pre-opening event for the NTT InterCommunication Center (ICC). It wasn’t exactly returning a favor, but in a way, we sent Takatani, who co-founded Dumb Type with Furuhashi, to the Sakamoto team for LIFE.

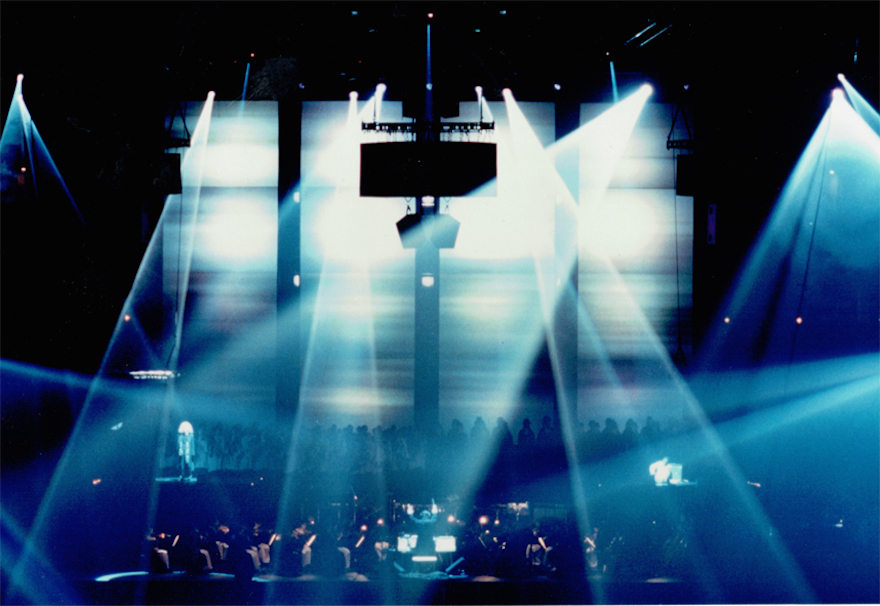

Moderator: Now, let’s watch an excerpt from LIFE.

[Screening of the excerpt of LIFE.]

Asada: LIFE was performed at the Nippon Budokan (Tokyo) and Osaka-Jo Hall. In the first part, the history of 20th-century revolutions, wars, and music is summarized through visuals and music. The second part presents a vision of ecological coexistence looking ahead to the 21st century, and the third and final part examines the multifaceted question of “Is there salvation?” The beginning features an imitation of the opening bassoon melody of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (1913), and towards the end, the melody transforms into a recurring theme for the Requiem without a savior. In between, 20th-century music is simulated successively, creating an astonishing masterpiece that could only be crafted by postmodern musical machinery. One notable segment features Churchill’s speech rallying the British people for a home ground battle against the Nazis, who had occupied France, adorned with Bartók-style music. Another part is Oppenheimer’s famous testimony recalling the atomic bomb experiment, stating, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” set to music resembling Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time. Consider these sections as Churchill’s Aria and Oppenheimer’s Aria. Oppenheimer, being a great intellectual, read the Bhagavad Gita in Sanskrit while leading the Manhattan Project to develop the atomic bomb. In it, Vishnu appears before Arjuna, who cannot decide whether to avoid the imminent battle. Vishnu speaks of the ethics of eternal recurrence, stating that the moment has been repeated countless times and will continue to be repeated and that even if Arjuna chooses pacifism this time, it will not change the course of destiny, therefore, he should accept his fate and fight. This dialogue culminates with the declaration, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” Meanwhile, from the second part onwards, various ethnic music, including Okinawan folk songs by the Okinawa Chans, accompanies biologist Lynn Margulis discussing the importance of symbiosis in the history of biological evolution.

Actually, after the performance of LIFE, Sakamoto-san and Takatani-san were planning to seclude themselves at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM) to create a DVD version. However, unexpectedly, an installation version of LIFE was produced instead, leaving only a recorded video for the opera version. This is fairly typical of creative artists, but it would be great to have something like a DVD book with essential information about the opera version of LIFE. For now, there is a booklet for LIFE, including a conversation between Ryuichi Sakamoto and me, and also a book called LIFE TEXT, a compilation of various quotes. I recommend these for a more in-depth understanding of what I have briefly explained here. – “Without LIFE, I wouldn’t be here right now.” Moderator: Now, let’s welcome the first of our guest commentators. We have Ms. Lucille Reyboz and Mr. Yusuke Nakanishi. They are the co-founders and co-directors of KYOTOGRAPHIE, the Kyoto International Photography Festival, of which eleven have been held to date. This year they have also initiated a music festival called KYOTOPHONIE. Interestingly, Ms. Reyboz’s life was literally changed by LIFE.

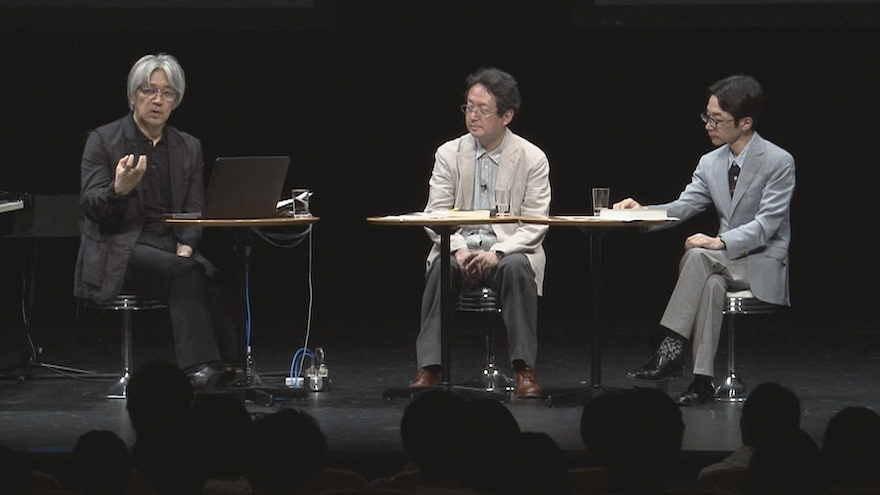

Lucille Reyboz (left) and Yusuke Nakanishi

Photo by Kenryou Gu

Nakanishi: Lucille always tends to cry when it comes to Sakamoto-san’s stories. She said she wouldn’t cry today…. Lucille Reyboz, originally a photographer, spent her childhood in Africa. Due to this background, she actively photographed record jackets for African musicians. Among them was the world-renowned musician Salif Keita, who was invited by Sakamoto-san to perform in his opera LIFE.

Reyboz: Salif asked me to accompany him and I stayed in Japan for about two months, capturing photos and videos. I had been a keen listener to Ryuichi Sakamoto’s music, and the invitation was extremely appealing to me, given my age of 26 at the time. My experience in Japan exceeded all expectations and was incredibly stimulating. Ryuichi possessed the talent to effortlessly transcend the boundaries of various music genres, blending classical and electronic music, while collaborating with outstanding creators from diverse fields. With Salif’s presence and musicians from around the world, including Mongolia, Okinawa, Sweden, Canada, Brazil, the project showcased a fusion of different musical traditions.

Everyone involved in the opera was inspired and had their hearts opened. Ryuichi not only looked back at the past but also opened the door to the future. We felt strongly connected to the world he envisioned and became a part of it. It was the most wonderful experience of my life.

I took a little video from backstage. I first met Shiro Takatani during the shooting, and later, various circumstances led me to live in Kyoto. If it weren’t for LIFE, I wouldn’t be here now. I am deeply grateful to Ryuichi.

Ryuichi Sakamoto, Yusuke Nakanishi, Lucille Reyboz, Shiro Takatani

Courtesy KYOTOGRAPHIE

I was deeply impressed not only by Sakamoto-san’s music but also by his statements on society and the environment. Through Lucille, we collaborated on the creation of the piece PLANKTON: The Origin of Drifting Life at KYOTOGRAPHIE 2016. During that time, I had a conversation with Sakamoto-san about life, and just listening to him was a profoundly moving experience.

Moderator: Nakanishi-san’s tearful dedication of KYOTOPHONIE to Sakamoto-san during the opening speech left a strong impression.

Nakanishi: It’s great to hear stories about Sakamoto-san from various people like this, and in Kyoto, there are many creators with connections to him, including those present in this venue. I hope that someday we can collaborate on exhibitions or stage productions about Sakamoto-san.

Moderator: That is definitely something to consider. Thank you very much.

Asada: As I mentioned at the beginning, Ryuichi Sakamoto was not the type of musician to say, “This is my song, listen to my song.” He was more like a mediator or organizer, interacting with various people, bringing them together, and encouraging a synergy that gave birth to various things. KYOTOGRAPHIE has become one of Kyoto’s defining cultural events, and it’s interesting to note that it all started through the good offices of Sakamoto. – Creation and Evolution of LIFE Moderator: Now, we have Mr. Takatani here, and he possesses invaluable materials, almost tantamount to trade secrets, regarding the creation and evolution of LIFE.

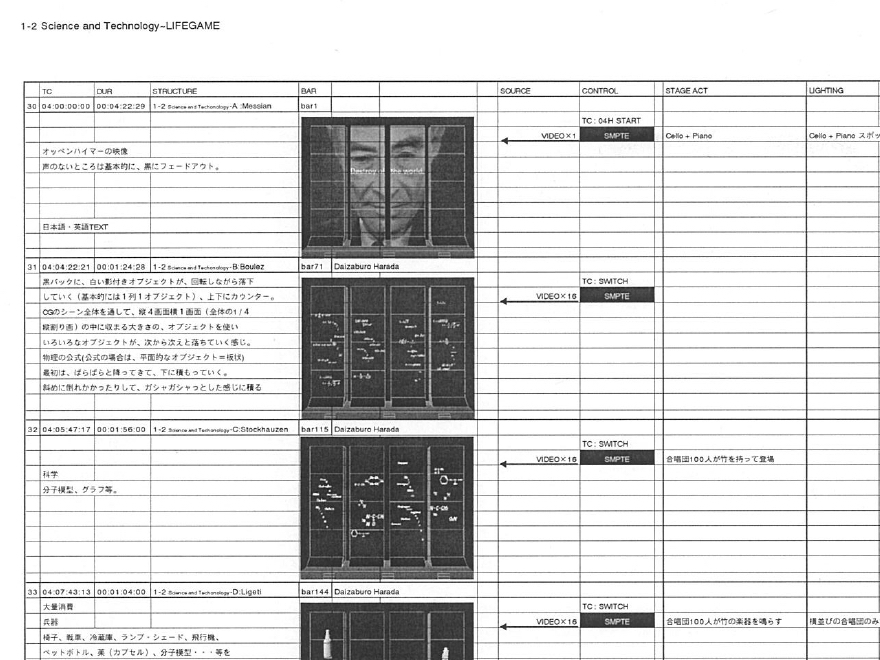

Score of LIFE

Courtesy Dumb Type Office Ltd.

Asada: The 1990s were still the analog era. Nowadays, AI might handle this kind of work, but having someone like this person was convenient (laughs).

Takatani: Absolutely (laughs).

Moderator: Asada-san’s role here is what we now call a “Dramaturg.”

Asada: No, I actually dislike dramas, and I also dislike trying to appear sophisticated by using German terms like Dramaturg. I was just an editor.

Takatani: Based on material like this we created a kind of timeline before entering the video editing room. Of course, we didn’t have access to all the footage, so Sora-san and others, who were managing the production, contacted archives overseas, obtained the rights for old videos and photos, and even prepared alternative footage in cases where we didn’t know until the last minute whether permission would be granted.

Moderator: Sakamoto-san said that the 20th century was the “century of war and slaughter,” simply put, the “century of destruction.” Is it accurate to say that the production started from assembling evidence for this?

Asada: While the first part of LIFE follows the history of revolutions and wars, the second part paints a vision of coexistence on the post-historical horizon. It explores how, from the level of nucleic acids, proteins, and microorganisms, symbiosis has shaped life on this planet.

Takatani: As we delved into the history in the first half, some have said that since this was a work created in Japan, there could have been more reflection on what Japan did in the past. However, including all historical events in the work was impossible, and this piece is not only from the perspective of “Japan” but was created with what all humans reflect on as humans in mind, and prioritizing significant events in human history. As Lucille mentioned earlier, it seemed important to capture elements that would hit the audience with a sense of “Can such expression be possible?”

Asada: From Sakamoto-san’s perspective, he had engaged with the memory of Japanese imperialism up to works like The Last Emperor . Then in LIFE he looked back on the entire 20th century more as an individual, addressing the question of how humanity would live in the upcoming 21st century. In the second part, themed around “symbiosis,” as mentioned earlier, we experimented with using the internet to connect dancers from various places around the world dancing at the same time. Since I had connections with William Forsythe’s Frankfurt Ballet, I brought in a highly talented dancer/choreographer from that ballet company, Tony (Anthony) Rich, and various others from around the world. In attempting to use the internet as a delay machine that creates slippage rather than realizing simultaneity, this showed Sakamoto-san’s characteristic approach as an artist. Although for better or worse, by this point the technology had already developed considerably, and there was hardly any noticeable delay.

Moderator: LIFE then evolved into installation form.

Takatani: In the process of creating LIFE we discussed how to transform the vast cache of material we’d collected into a work—whether through DVD-ROM, or some other suitable format. Since opera is a performing art with a beginning and end, this was an inevitable discussion. However Sakamoto-san sought a way for the audience to experience the work on a parallel timeline rather than a linear one. Which is why an installation format seemed most suitable.

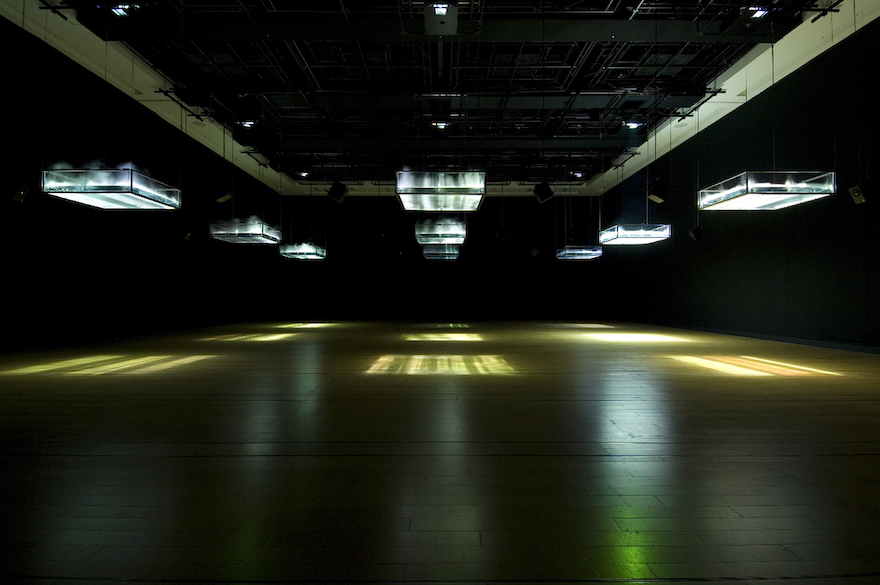

Ryuichi Sakamoto + Shiro Takatani, LIFE – fluid, invisible, inaudible…, 2007

Photo by Kazuo Fukunaga

Ryuichi Sakamoto + Shiro Takatani, LIFE – fluid, invisible, inaudible…, 2007

Photo by Ryuichi Maruo

Takatani: The work has nine tanks suspended from the ceiling, each 1.2 meters square, filled with water. Ultrasonic devices similar to those used in humidifiers generate mist in the water, and projectors project images onto the mist from above. In a completely dark space, visitors walk through as if strolling in a garden where nine water tanks are floating, viewing and listening to historical footage used in LIFE and interviews with various artists and intellectuals commissioned by Sakamoto-san.

Ryuichi Sakamoto + Shiro Takatani, water state 1, 2013

Photos by Ryuichi Maruo

Another piece, Forest Symphony, was created in collaboration with Sakamoto-san and YCAM InterLab. Trees convert solar energy through photosynthesis, and this work captures the bioelectric potential difference of trees from around the world as data. It then creates a “symphony by the forest” using the difference in electrical potential to generate sound.

Ryuichi Sakamoto + Shiro Takatani, LIFE – WELL installation, 2013

Courtesy Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Asada: I must mention that, although this is the work of Sakamoto-san and Takatani-san, much credit goes to fog sculptor Fujiko Nakaya. Her father, Ukichiro Nakaya, known as the “scientist of snow,” was a pioneer in the artificial synthesis of snowflakes. Fujiko Nakaya has been active as a fog sculptor since participating in the 1970 Osaka Expo Pepsi Pavilion project as a member of the E.A.T. (Experiments in Art & Technology) group. She is now recognized as a pioneer in environmental art. E.A.T. included artists like Robert Rauschenberg, and engineers such as Billy Klüver. In Osaka, David Tudor, known as Cage’s pianist and also a unique composer in his own right, played a significant role within the group. They asked Fujiko to do something for the “ugly” pavilion building, and that’s how the mist covering began. It’s an interesting building, but because E.A.T. followed the Buckminster Fuller philosophy, they weren’t pleased it wasn’t a Fuller Dome.

Fujiko is also a pioneer in video art, having experimented with communication networks using video as a medium, calling it “Video Hiroba,” (Video common) even in the pre-internet era. She gave her support to young, emerging video artists like Bill Viola, Gary Hill, Teiji Furuhashi, and Takatani-san. So Takatani-san has in turn supported her, like a dutiful son.

Takatani: Not really (laughs).

Asada: This work, LIFE-WELL, has mist emerging from a pond resembling a well surrounded by stone walls. Just like in LIFE – fluid… mentioned earlier, mist rises above the water tank, and projections come down onto it, creating beautiful layers similar to frost needles.

Takatani: Thank you. Nakaya-san’s mist is not a chemical mist using oil fog machines but rather a mist made of safe, drinkable water, akin to real clouds. Sakamoto-san was very interested in that. In LIFE-WELL, mist nozzles are installed under the bridge. When mist comes out, its shape is captured by a camera, and the sound changes according to that shape. So, it’s not music composed by Sakamoto-san playing; it’s how the mist changes in this compact environment that alters the music. Once again, note the lack of a “listen-to-my-song” attitude.

Asada: Watching this with me, Nakaya-san said without any malice, complimenting the beautiful work, “When Sakamoto-san and Takatani-san do it, even mist becomes fantastic art. I’ve always been anti-art.” Given her background working with Rauschenberg and Tudor, it’s an interesting comment. It’s as if she is saying, “In the wake of my constant commitment to anti-art, is it really OK to return to such beautiful art?”

Ryuichi Sakamoto + Shiro Takatani, LIFE – WELL performance, 2013

Courtesy YCAM

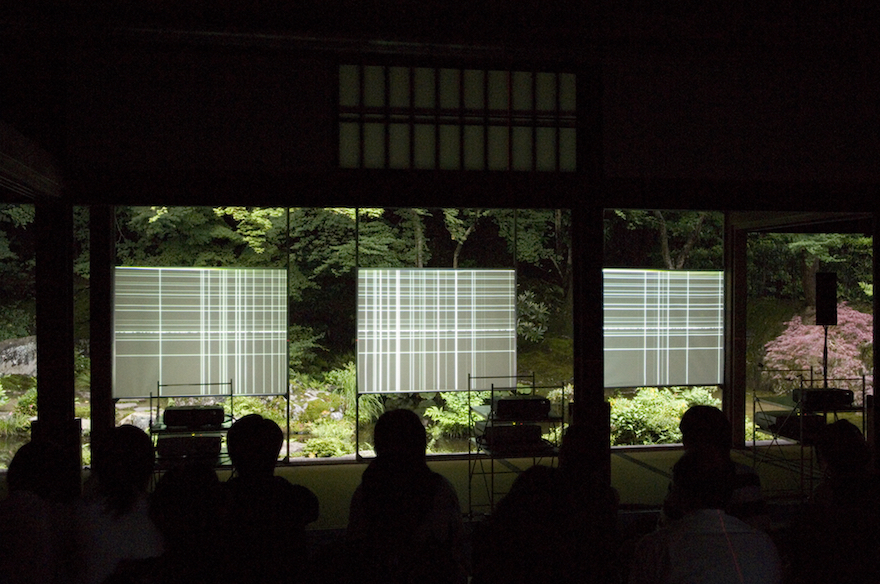

Live performance at Honen-in temple, 2005

Photos by Kazuo Fukunaga

Takatani: Sakamoto-san has always been interested in Kyoto, but he often said, “I don’t particularly like what is commonly referred to as tourism.” One day, I learned of various events taking place at Honen-in and thought it would be nice to have a live performance with Sakamoto-san at a temple. Sakamoto-san said, “I’d like to listen to music with about five people while looking at the garden,” (laughs). I set up three small screens facing the garden and projected prepared videos onto them in a random fashion. It was basically a live event where Sakamoto-san played music like a DJ, and the audience sat on tatami mats and enjoyed the performance.

Moderator: Just five people would have been pushing it I think (laughs). How many attended in the end?

Takatani: Around 70, I think.

Asada: What was interesting is that Sakamoto-san noticed that frogs responded to a certain sound by croaking. So he began to conduct the frogs during the performance, emphasizing that the croaking of the frogs was also part of the music.

Live performance at Yotoku-in, a sub-temple of Daitokuji, 2007

Photos by Susumu Kunisaki

Asada: Actually, we initially asked Sosho Yamada, head priest of the Shinju-an sub-temple at Daitoku-ji, if we could use Shinju-an. However it was so beautifully and perfectly crafted that there was no room to insert new art, so we decided to choose another location. When we were chatting in the Teigyokuken tearoom of Shinju-an (which is said to be favored by tea connoisseur Sowa Kanamori), it suddenly started to rain. For a while we listened in silence to the raindrops hitting the roof. That seems to have been an unforgettable experience for Sakamoto-san. To borrow a pun from artist Hiroshi Sugimoto, it was like Uchoten (the name of the tearoom at Sugimoto’s Enoura Observatory, meaning both “feeling on top of the world” and “listening to the sky with rain”).

Takatani: At the Yotoku-in we installed three mirrors in the garden, the angles of which could be adjusted using motors, allowing the audience to look at the sky reflected in the mirrors. Sakamoto-san played music in DJ fashion during this event as well. It began with very delicate, almost imperceptible sounds, and before you knew it, you felt surrounded by the music.

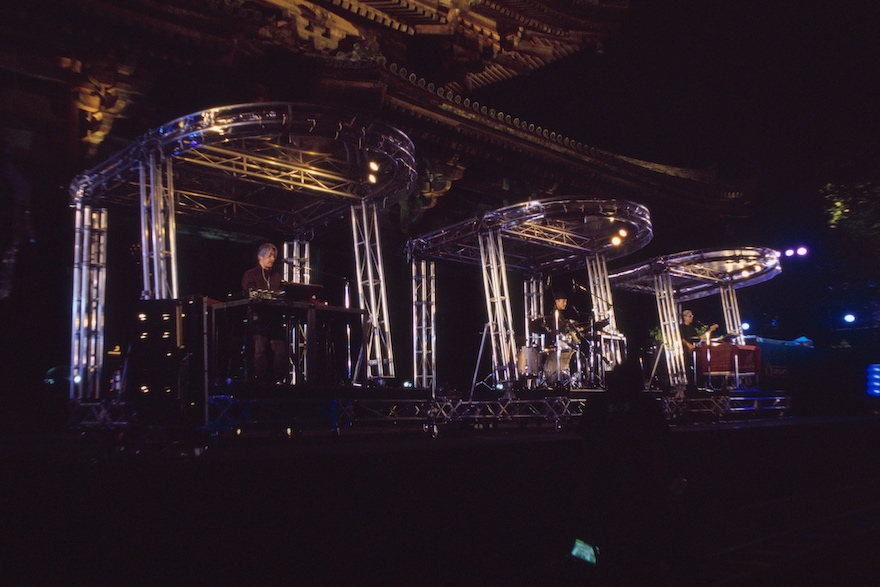

Yellow Magic Orchestra, “Live Earth,” Toji temple, 2007

Photos by Itaru Hirama

Asada: Michael Nyman also performed there. Despite his talk of post-minimal music, he had actually returned to tonal music, continuously pounding chords, which I wasn’t that fussed on at all….

Moderator: Moving slightly back and forth here, in 2005 a Susan Sontag Memorial Symposium was held at the Kyoto Art Theater – Shunjuza (currently part of Kyoto University of the Arts, formerly Kyoto University of Art and Design). Sontag was a prominent American intellectual, critic, novelist, theater director and filmmaker. Unfortunately, after a long battle with cancer she passed away in 2004. Since Asada-san was close to her, we thought of doing something in Kyoto. A symposium was held right here, followed by a live memorial performance by Sakamoto-san and Takatani-san.

Asada: The novel In America was quoted in the video, but in the end, only punctuation marks remained, and the music ended with noise… I’ll never forget the tremendous crash of the thunder at that moment.

Artist Summit Kyoto, 2007: (From left) Tatsuo Miyajima (moderator), Keun Byung Yook, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Ingrid Mwangi, Krzysztof Wodiczko, Gülsün Karamustafa, Jarupatcha Achavasmit

Courtesy Kyoto University of the Arts

With Junichi Konuma and Akira Asada at a live recording of Sukora, 2010

Akeo Okada (right)

It was a bit surprising to me that, for the Sukora series focused on classical composers, Beethoven was chosen after Bach. I expected Sakamoto-san might delve into Debussy, Satie, Cage, or minimal music. Beethoven’s intensity and cerebral quality seemed to somewhat contradict the “Ryuichi Sakamoto = Postmodern” image, so it was a little unexpected.

Anyone who knew him directly would probably agree that Sakamoto-san was very sincere —almost unusually so for an artist. His strong desire to be an honest citizen seemed to take precedence over being an artist. One suspects this tendency had its roots in his upbringing.

One more thing to note is that Sakamoto-san, although a top student at Tokyo University of the Arts (Geidai), was quite unexpected in his choice of composition teachers. The top students in Geidai’s composition department at the time often studied under Yujiro Ikeuchi, a French-influenced teacher. Students with an admiration for Debussy or Ravel tended to end up under Ikeuchi’s wing. However, Sakamoto-san’s teachers were Kanichi Shimoosa and Yoshio Hasegawa, both German-oriented and disciples of Kiyoshi Nobutoki, known for Umi Yukaba, a popular song among the military, especially with the Imperial Japanese Navy. It’s quite surprising that Sakamoto-san was a “grand-disciple” of Kiyoshi Nobutoki, but it may explain his deep admiration for Bach and Beethoven.

Moderator: Indeed, Sakamoto-san is generally associated with French music, so I think you have provided some very valuable testimony there.

Okada-san, we will hear from you again later, but for now, thank you very much. – Mallarmé Project Moderator: Next, let us watch a video from the Mallarmé Project, which took place three times over a span of three years starting in 2010. The venue, once again, is here at the Shunjuza. The project was conceived by the late French literature scholar and director Professor Moriaki Watanabe (who served as the director of Kyoto Performing Arts Center at this university) in collaboration with Asada-san. Professor Watanabe also directed the performances, with readings by both himself and Asada-san. Takatani-san was responsible for visuals and set design, while Sakamoto-san handled the music and sound. From the second version onward, dancers Tsuyoshi Shirai and Misako Terada joined the project.

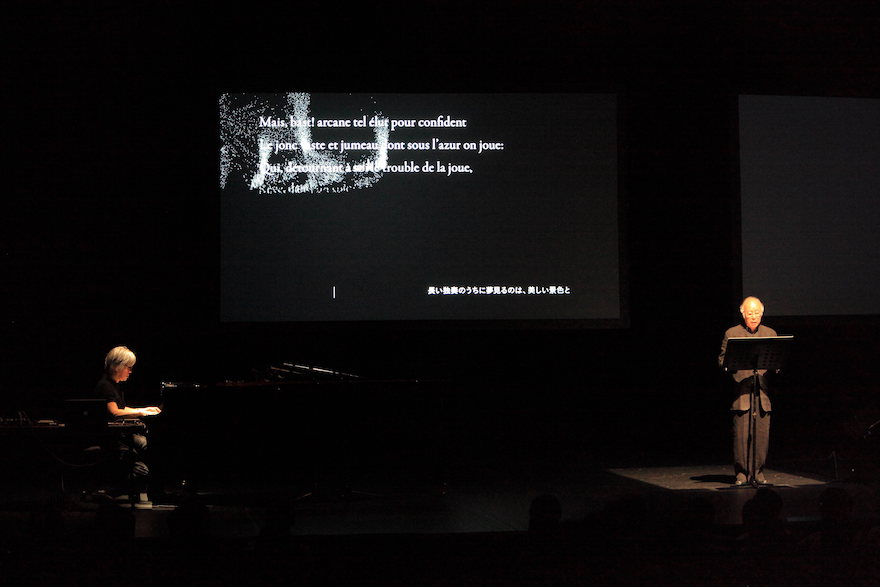

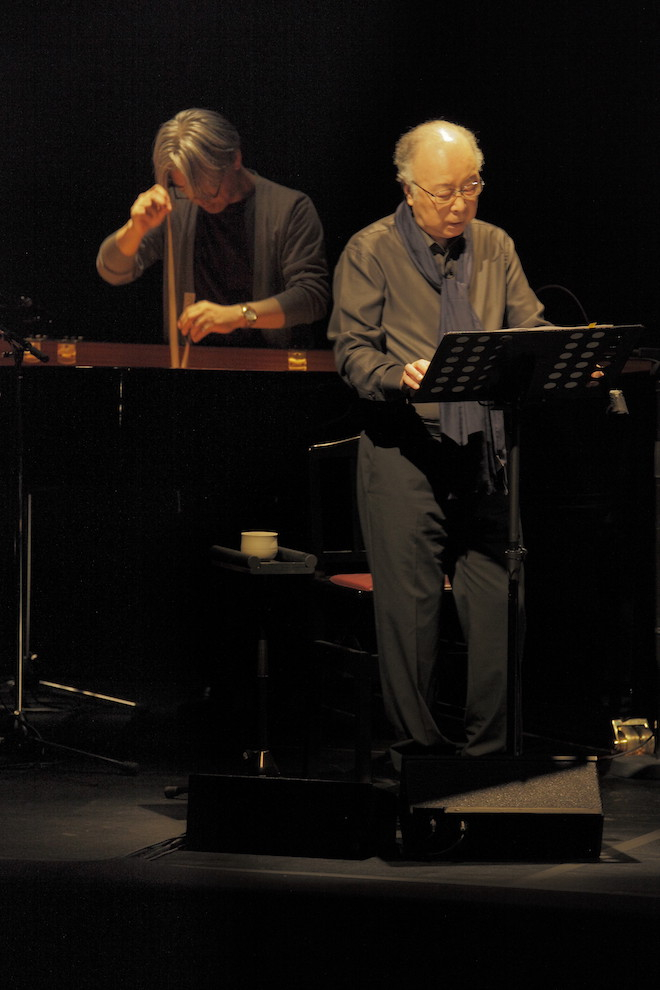

Mallarmé Project I, 2010

Photos by Toshihiro Shimizu

The poem “The Afternoon of a Faun” (1865-67) by symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé was written with the intention of being recited at the Comédie-Française, but the performance was rejected. In 1894, Debussy composed Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun, and in 1912, Nijinsky of the Ballets Russes choreographed and danced it himself, causing a scandal (the half-beast god, who had let the nymphs [water spirits] flee, makes a gesture reminiscent of masturbation at the end). However, especially in Japan, perhaps because Shintaro Suzuki’s translation was too old-fashioned and difficult to understand, many people only knew the name. Professor Watanabe retranslated it into an understandable form through oral reading, and he read it himself. Sakamoto-san, who loved learning, saw this as a perfect opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of Debussy and despite his busy schedule, accompanied us three times.

Mallarmé Project II, 2011

Photos by Toshihiro Shimizu

The Mallarmé Project unfolded assuming such trends implicitly. In the third production, we took up Mallarmé’s speculative novel Igitur (something like an abstraction of Hamlet) and recited it, incorporating several other poems. The dance theater and visuals adorning this, especially the subtitles in French and Japanese on the screen, were beautifully created under the direction of Shiro Takatani, with programming by Ken Furudate. Mallarmé would likely have rejoiced to see the countless points gathered to form letters like constellations, only to scatter again. In the end, “Afternoon of a Faun” was also recited, and listening to Watanabe-san’s well-paced reading was delightful. The dancers dancing naked behind a semi-transparent screen seemed to modernize the Impressionist water bathing scenes. Above all, I was once again amazed at Sakamoto-san’s exquisite improvisation in adding music with a minimum of coordination beforehand.

Takatani: Here is a view of the stage from directly above [shows a stage diagram]. Two large semi-transparent screens are installed on the rotating stage, opening like a book at 120 degrees. The screens can have images projected on them even as they rotate. We designed the stage like this for Igitur because it emphasizes changes in the timeline, shifting to the middle of the night, for instance.

Sakamoto-san plays the piano on the left, and on the right, Watanabe-san and Asada-san sit at the table and proceeded with the recitation. On the table is a crow from the PixCell series created by Kohei Nawa.

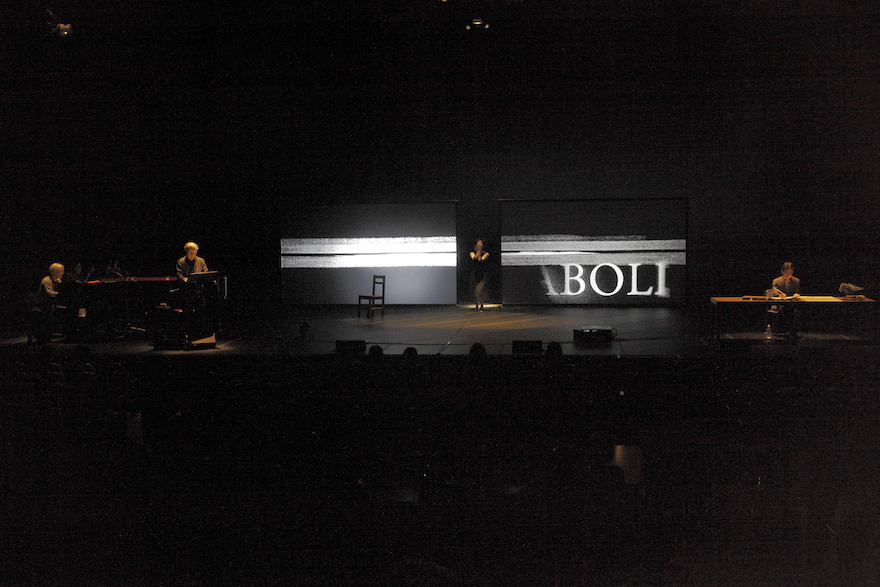

Mallarmé Project III, 2012

Photos by Toshihiro Shimizu

Watching a portion of the footage here, it feels like a dream that such a performance could have taken place in this theater. While it’s unfortunate that we couldn’t further refine and preserve it, like LIFE there are at least three recorded versions, and I think they ought to be compiled somehow, as a valuable legacy of the production.

Staff and cast

Photo by Toshihiro Shimizu

With Professor Moriaki Watanabe

Photo by Miho Kawahara, courtesy Kyoto University of the Arts

(End of Part 1)

This symposium was held on June 18, 2023, at the Kyoto Art Theater – Shunjuza.

Organizers/Operators: ICA Kyoto + Kyoto Performing Arts Center, Kyoto University of Arts

Planning cooperation: Kab Inc./ KAB America Inc. + Dumb Type Office Ltd.

Allow us to express our gratitude to the attendees for their generous contribution. Thank you all.

*Click here for Part 2.