Conversation between Nakahara Kodai and Sekiguchi Atsuhito : 2. In Kyoto

Moderator: Ozaki Tetsuya

Moderator: Ozaki Tetsuya

About three weeks after their conversation at the Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art, I asked the two artists if they’d oblige with a “sequel.” Partway through, a conversation that started with observations on the differences between video and painting as media took an unexpected turn. Nakahara Kodai is said to have “started distancing himself” from the so-called art scene following his participation in the “Aperto” section (1) of the Venice Biennale in 1993. However according to Nakahara, this breakaway was actually occasioned by the “Anomaly” exhibition (2) a year earlier. It is common knowledge in the art world that in this group show curated by Sawaragi Noi (3) and featuring Nakahara, Murakami Takashi (4), Yanobe Kenji (5) and Ito Gabin (6), Nakahara presented a work bearing an uncanny resemblance to one previously unveiled by the younger Yanobe. The truth about this incident – taboo at the time, never spoken of subsequently either – will be revealed here by the artist himself.

Nakahara Kodai and Sekiguchi Atsuhito / photo Kanamori Yuko

— Following the conversation at the Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art, Nakahara-san, you said there were still things left to discuss, and requested a second meeting. This time, can I just leave it entirely to you two (laughs)?

Nakahara : Sure. So can I start with a straightforward question? How long were you at IAMAS (7)?

Sekiguchi : Seventeen years. From 1996, I think.

Nakahara : How did you find it there?

Sekiguchi : In what respect?

Nakahara : That media art sort of stuff was pretty big back then, wasn’t it? I just wondered what it felt like to be in a place like that at the time.

◆Differences between video and painting

Sekiguchi : One thing was that having, since around the mid ’80s, no longer demanded of myself much in the way of grounds for the actual decision-making involved in producing works – decisions about things like motif and theme, that is – I wondered if it might be feasible to move toward purely calculation-based ideas. So I started experimenting with using a computer.

Nakahara : Up to then you’d said you wouldn’t do that sort of thing in physical form.

Sekiguchi : By which I meant, not produce any material output.

Nakahara : But then partway through you start wielding a paintbrush again, surely? Perhaps this was before IAMAS, but did some change occur that stemmed from what you were thinking at the time?

Sekiguchi : In the case of painting, part of me doesn’t think of it as being “material,” so I don’t really feel like I reverted to the material. Sure, there’s this field we call painting, which serves as a place to churn out images per se, but I’d never thought of it much in material terms.

Nakahara : There must be something in computer-aided methods that prompted you to use them.

Sekiguchi : I suspect I shifted to the computer and stopped painting because I lost patience with the processes involved in thinking up works, placing the colors and so on. With a computer things just appear, ready for use.

Nakahara : Meaning, in other words, you could skip those processes?

Sekiguchi : Yes. I find it more interesting to use a computer to find a basis for the work, using mathematical formulas and algorithms to an extent to come up with some sort of form. Plus it seemed to me the closest to a kind of stripped down sensation.

Nakahara : So why is it from that time in Sendai (8) you…?

Sekiguchi : Went back to painting, you mean? That’s quite a while ago, what year was it now…?

Nakahara : 2004 or 5, I think.

Sekiguchi : By about 2003 I was thinking it’d be OK to paint, but in the end on that occasion too, rather than painting, what I really wanted to do was for instance to go to various islands, seeking the sensation of painting alongside experience. Computers failed in quite a few ways to cater to my requirements. Some things were too challenging for the technology, the algorithms of the time. If I were a mathematician I could just get stuck in and do it I suppose, but I’m not, nor do I possess that kind of ability. Conversely, having been 17 years at IAMAS I have a fair idea of what can and can’t be done by computing. In fact, in the last two or three years our understanding of consciousness, of the brain, of human life, of the great questions of the universe has been transformed, and when moves emerge to analyze it all properly, I imagine computers would come in very handy.

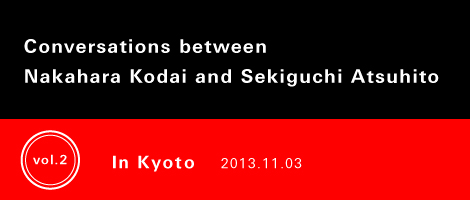

All: Sekiguchi Atsuhito

Ni Fu U Ke I 2, oil on canvas, 162.1x184cm

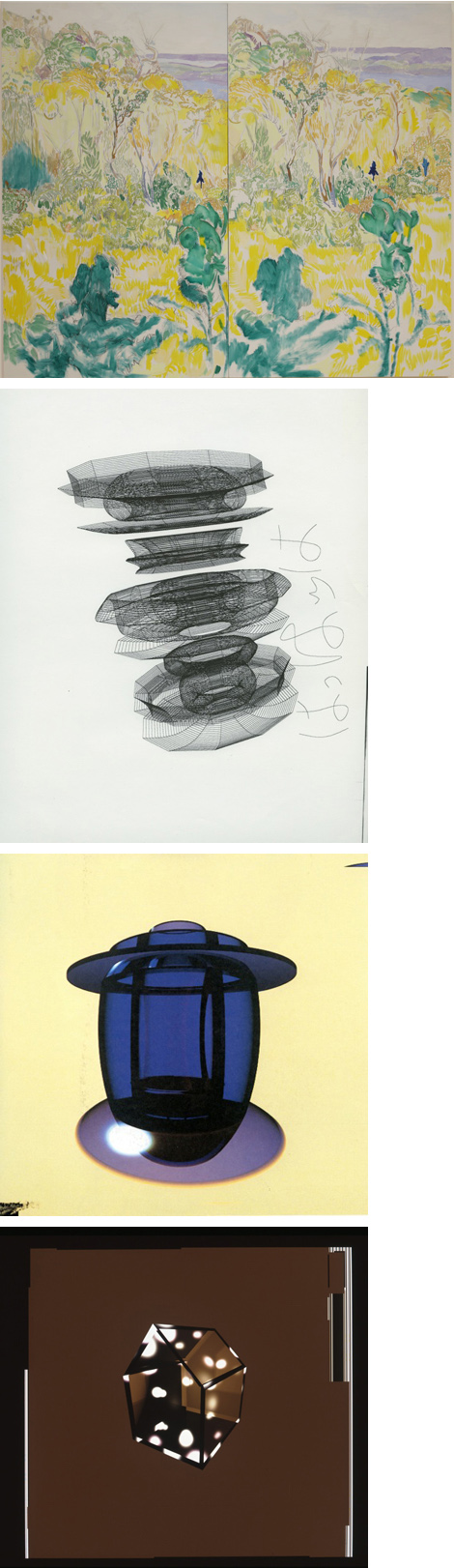

Solid of revolution of laughter, 1989, computer-generated plotter print

Solid of revolution of laughter, 1990, computer-generated print

House102 (Light house), 1989, computer-generated print

Nakahara : That includes at the level of artistic output, I assume? But it strikes me that to produce a thing as video imagery and to paint it are very different, surely?

Sekiguchi : Well, assuming you made them with the same object in mind, on video and in a painting I imagine they’d manifest in totally different forms.

Nakahara : So what is the difference? Video has this image of lacking substance, surely? I wondered if you’d gone back to painting because video alone “wasn’t enough.”

Sekiguchi : With video, if for example your body were made of mercury or suchlike, it would feel like images being projected on the surface. Being made of mercury your body could assume any shape, could even stretch, rubber-like, and it would be like an image was stuck to that. With paints, the colors might be the same, but the image inevitably seems to spread out across the surface, enveloping the contents. There’s nothing in between the two.

Nakahara : Is it that video feels very close to the real thing?

Sekiguchi : How to describe it…I imagine there could be video that appears to wrap around blobs of color, and the images I draw in my head have the same feel about them but… There’s that pebbly clump you made at the very beginning, the colors.

Nakahara : Which one was that?

Sekiguchi : The one that got broken and lost. What was that made of?

Nakahara : FRP, maybe. Was that a “video”?

Sekiguchi : No no, “paints.”

Nakahara : “Paints”? Oh, I see.

Sekiguchi : Mmm. Conversely that sense of all sorts of things arranged in parallel in fragmented form with different images quickly overlaid is “video,” I think.

Color volume Vol.2

1983, FRP, pigment, white marble, and other materials

(Installation view at Polyparallel 1, G art gallery, Tokyo, 1983)

◆A desire for more intense, direct stimulation

Nakahara : In asking those questions, I wanted to confirm that there was something in what you might call the insubstantiality of computers. That’s what I anticipated, anyway. I remember saying you didn’t need your work to have a physical form, so surmised that there had been a kind of correction, but that’s not the case, it would seem.

Sekiguchi : No, it’s not.

Nakahara : Does it mean, conversely, that you’ve never assumed a thing to exist solely as data, a state of truly no substance? Is mercury indeed required?

Sekiguchi : Something akin to mercury. A mercury-like state, of sorts, if one were to deliberately give it form.

Nakahara : That will do, I guess. But don’t you find, conversely, people around you who push on, affirming that insubstantial state?

Sekiguchi : One’s output changes in various ways, so I suppose it is viewed in various ways too.

Nakahara : Meaning it doesn’t jar with having said that you didn’t need your work to be “physical”?

Sekiguchi : What kind of objects did you see those “physical” things as being?

Nakahara : Things that exist there. Harking back to what we were saying earlier, mercury exists, and is projected on there. As if mercury and image were stuck together. As to whether the state of being shown on that surface exists as a sensation or not, I imagine you’ve always leaned toward it doing so. In that sense, maybe I’m very close to the “not” camp. However, does this therefore mean I can accept it not being there? From my actual feeling, I doubt it. I don’t really know if I’m deliberately trying to think that.

Sekiguchi : But in experiential terms surely you produce nothing but works that conjure up that sort of idea?

Nakahara : Meaning…?

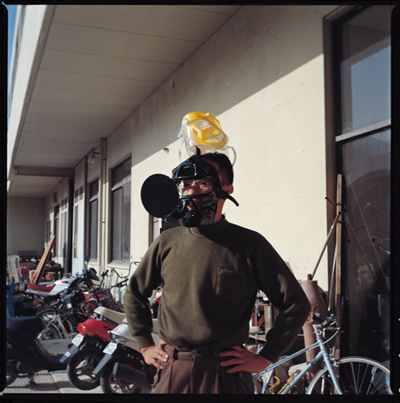

Sekiguchi : For example the ones with stuff stuck on your head (9) we talked about in Okayama. Putting that headgear on, one feels uneasy. A lot of your works offer that kind of sensation in tangible form. That’s why I found them so interesting when I first saw one in Kyoto.

— When was that?

Sekiguchi : In the early 1980s. When I asked if you wanted to do a show together. I’d never seen an artist producing that sort of thing in such a straightforward fashion. It was intriguing.

Nakahara : Can you jog my memory on that?

Sekiguchi : When we planned that show called “…polyp” or suchlike. Not that it ultimately came to fruition. I was wondering if it would be possible to show people the actual state of envisaging something shapeless, something originally “feels like this,” and there you were, just doing it. Sometimes there is a shape, sometimes there isn’t any at all, and sometimes you present it as that kind of experiential device. What were you feeling when you made those headgear pieces?

Nakahara : To be honest, I was striving for an emotion rather more vulgar than that. They told me a boy about elementary school age who came to the Okayama show started giggling when he saw it. As far as reactions go, for me that’s as good as it gets. Plus, the body is made from leftover parts from a radio-controlled car, and there’s a sense of being able to play with it here, there and everywhere. On first donning one you tense up, your heart starts to race a little. The catcher’s mask has something black sticking out of the mouth, a stay used for displaying model jumbo jets. I just love that way some other nerd in the know will think hey, that’s a stay for a jet. I was less interested in deep, expanding emotions than stuff happening instantly, electrically.

Sekiguchi : But it’s not that you home in on that right from the start, is it? Although the general sensation is I imagine consistent, and arises from the same source.

Nakahara : But although not obvious when I did that headgear, by then I’m already starting to run, as a preface, so to speak, and losing my detachment. It’s like I want to escalate things fast, to be stimulated more intensely.

Sekiguchi : I now understand that you were probably looking at things from a different angle, but at the time nobody really knew what you were up to.

— With that work, by wearing the headgear, the person doing the wearing and the person looking on embrace some kind of emotion or image, in the way that child laughed. Was that the purpose of the work?

Nakahara : Not so much that as, like hurtling full speed into that kind of realm. The question ultimately is whether that acts as a stimulus to myself. It’s not about this kind of emotion being hidden and that kind of mechanism sustaining that: someone laughing hysterically is more my “desired stimulation”. I’ve said it a number of times in connection with my Lego pieces as well: it’s not about what they mean, or how they came about. I’m happier if for example to be confronted by some guy grinding his teeth in excitement. Right from back then, among all the reactions I’ve seen and heard at art venues and other settings, there are some that cannot be viewed as stimulating, and when I try to pick up on those that can be seen as stimulating, they rapidly morph into something of that ilk. So rather than looking to be rich and profound in my work, I rapidly slide off in a stronger, more direct direction. Ever since a certain point in time, whenever I tumble, I find it is stimulation that was guiding me.

Sekiguchi : In my case, I make works with a sense of creating visually massive volume, but you’re different, and that’s what’s interesting. Generally I suspect people think a little more about the logical aspects, like mechanism, structure, when making things, but that’s not your starting point at all. The viewer inevitably tries to look at it logically, but you’re expert at making things while emphatically not in that state.

Nakahara : My own desires with regard to that get more and more pressing. It can’t be helped, really. Once I fall into that mode, it all starts to run away with me.

Headgear3 (Insect cage)

1991, Insect cage, catcher’s mask, plastic model

*Origianl destroyed, remade in 2013 (unfinished)

Lego, 1990-91, Lego

Collection of The National Museun of Art, Osaka

Photo Mukaiyama Kazushi

◆Shock of the “Magiciens de la terre” exhibition

Sekiguchi : At times like that, how conscious are you of your work being fine art, or art?

Nakahara : Initially, for instance when I made figurines at the Satani Gallery (10), or produced the revolving chair, I did have special dispensation of a sort, because partly I was convincing myself: saying see, I’m doing and showing this sort of stuff. The flip side of that is, you’re discarding responsibility for yourself. “I can do whatever I fancy because I’ve relinquished all responsibility.” I start to really loathe that.

Sekiguchi : On the other hand people are certain to demand that sort of thing from you, surely? Or perhaps it’s just the artist thinking that.

Nakahara : Which is why, according to the review you wrote, Ozaki-san, “Aperto” (1993) triggered the emergence and morphing of a story within myself, but in fact it was “Anomaly” (1992). For “Anomaly,” I exhibited a work that seemed a copycat version of one by Yanobe Kenji, but by doing so, I knew I might as well abandon any pretensions to professionalism. So I made a decision. It felt like what the hell, I don’t care if I’m no longer an artist, let’s just do it.

— It didn’t matter that people would think you were copying him?

Nakahara : Exactly. Inside I knew I should put a stop to it, because as an artist I knew it wasn’t on, but for example, if the person who makes a work uses a particular toy to play with, no one complains do they? If you abandon any viewpoint of doing it in a public setting, that is, if you make it like playing in your own home, those restrictions disappear. So I decided to take that tack. Since making that decision, my mindset has changed completely.

— So that’s what happened…

Nakahara : What I imagined, or rather maybe what I expected, was that I’d get a drubbing for it. But no one mentioned it. Not a word. Not what I anticipated at all.

Sekiguchi : It was taken in completely the opposite way, right?

Nakahara : That’s right, as in, similar but different, that sort of thing. Yet for my part, I thought I’d face the rejection of the whole meaning of my being there. Instead I found myself completely off the hook.

— Some say that to show you thought of the isolation tank concept before Yanobe-san, you exhibited dated drawings…

Nakahara : Dated drawings? I don’t remember that.

— What I mean is, if your intentions were as you say, that’s nonsense isn’t it?

Nakahara : Maybe I was doing that, in terms of the date on which the idea occurred to me, it is possible. The problem is that systemically, such a thing wouldn’t happen. So in that sense, I may well have done it. Moreover, the piece displayed was obviously unfinished – me having gone off on a university study trip to India or somewhere without completing it – but I deliberately left it like that. Meaning I felt it would be OK like that.

Module for floating with me and my wife, or our future child

1993, Iron tank, thermometer, fan, silicon rubber doll, and other materials

Installation view at Venice Biennale – Aperto ’93: “Emergency/Emergenze” 1993

*Tanks no longer existant

— As mentioned in your conversation at the Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art, on the caption for Gifucho it says that your thinking changed significantly after viewing the “Magiciens de la terre” exhibition (11) in 1989. Is that connected to what you’re discussing here?

Nakahara : In 1989 there was a kind of Belgium-Japan year, and Minemura Toshiaki (12) planned a group show of Japanese artists within an outdoor sculpture exhibition. (13) I showed things like the Snoopy-like stones that were at the Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art. While I was there I saw “Magiciens de la terre” at the Pompidou Centre, and “Open Mind” in Ghent. (14) It was these that made me think, hang on… And I guess if this story has a beginning that was it.

— What do you mean by “hang on…”?

Nakahara : That outdoor sculpture exhibition started with people like Lee Ufan (15), Suga Kishio (16), Koshimizu Susumu (17), and Sekine Nobuo (18), and included Toya Shigeo (19). It went right down through the generations, with the likes of Aoki Noe (20) and me being the youngest. At the time I myself was aware of “being there,” and was trying to think how to move from there to the next thing. But “Magiciens de la terre” mixed things like shamans, like folk art, with contemporary art. “Open Mind” featured paintings by the so-called mentally disturbed, alongside the work of artists like Ensor (21) and Magritte (22). What struck me then was how contemporary art completely failed to measure up. I can’t recall feeling the slightest bit moved. The huge difference between them was the difference between something with all its limbs wrenched off and devoid of teeth, and something truly dangerous, and not surprisingly, that kind of thing is vastly more powerful, and there really are things capable of transforming a person’s life. I suddenly wondered why I hadn’t being invited there as a magician, why I wasn’t there as one of the mentally disturbed? What exactly was I aiming for? It felt like my whole desire to become a contemporary artist had been misguided to begin with. Not, mind you, that I felt there and then that I wanted to turn into a magician or someone with a psychiatric disorder.

◆Ready to give it all up

— Then came the “Anomaly” show. That was a year or two before “Aperto,” wasn’t it?

Nakahara : Yes, that’s right. I came back from Belgium and made a piece from yarn, Viridian Adaptor at the Muramatsu Gallery. (23) With a glove piece for putting your hand in that I hadn’t done before. Up to then all my works had been just for looking at.

Sekiguchi : What year was that wool piece?

Nakahara : ’89.

Sekiguchi : How about Date Machine?

Nakahara : ’91 I think. What I found myself saying a lot around that time was that while there may be only a minor shift between trying to move something, and something moving, for me it was a huge adventure. That moment, I mean. But at the same time, still carrying the burden of a kind of history I was trying to shoulder. I felt this was pushing it a bit, and well, you could say I chose the easy route, but I decided to give it all up. To shed the whole of that load, and refuse to be responsible. The next step would have been to say OK, if all connection to that is now severed, how should I start to make things?

— The next step being “Anomaly”?

Nakahara : Stuff like the Lego, and Post Hobby (24) that I did at the Satani Gallery. First I had to start thinking about what to hang my work off, so to speak, and came up with a number of ideas: Lego, freezers, that sort of thing. It felt like first taking some parts not filled in myself and refilling them: several emerged, so for a while I worked on tucking them away. In the process, things I managed to retrieve in the task of filling, things that developed anew, carried on. But most ended, in terms of my mood, on the way to “Anomaly” etc. I felt that perhaps I’d done enough of that. Then, getting back to what I was talking about earlier, I do various things, but I started to feel, very strongly, that whatever I did I’d be safe doing it, because my own responsibility is still safely stashed away somewhere else: I suppose you could say I felt I had “special dispensation” that let me get away with that.

— Meaning, you’re part of the art world?

Nakahara : Yes, yes. My next thought was that in order for the responsibility for what I was doing to sheet directly home to me, I supposed I’d have to fuse the desire to do whatever I felt like, and my responsibility as a professional, as a member of society. And from around “Anomaly” onward, it feels like I headed in that direction.

Foreground: Viridian adapter + Koudai-no-morpho II

1989, woolen yarn (Viridian adapter) / Oil on plywood (Koudai-no-morpho Ⅱ)

Background: Electric revolving chair – What Nakahara Kodai can do for Kodai-shonen

1991, mixed media

Courtesy Toyota Municipal Museum of Art

Date machine, 1991, mixed media, dimensions variable

Installation view at “the First Canon ArtLab, 1991, Gaienmae TEPIA, Tokyo *Destroyed

Photo Narita Hiroshi

Sekiguchi : “Magiciens de la terre” was put together by Jean-Hubert Martin (25), and in the end, chimes exactly with what those such as Lyotard (26) were thinking. In short, people in places like Africa and South America took on board, through capitalism, the tools of art whose progress has been Western-centric. In assembling the show, he posed the question of how to position the expression of these people.

— Sekiguchi-san, how did the change in Nakahara-san after 1989 strike you?

Sekiguchi : I didn’t even notice any change at that point. I thought he was simply motoring on.

Nakahara : As in, that guy’s not going to last long (laughs).

Sekiguchi : If I thought about it at all, I just assumed you were doing what you wanted to do. There was a strong feeling that rather than viewing and commenting on individual pieces, understanding would only come with closer inspection.

— In the discussion on the headgear, Sekiguchi-san pointed out that it was the kind of work that “offered up sensation as object.” Were there no more works like that after 1989?

Nakahara : I love that sensation of something in my head appearing and coming into being, just as is. I can think of when that happens in some types of my work.

Sekiguchi : But while up to Gifucho you were doing that, subsequently, that need has clearly gone. Even in Gifucho you seemed to exude that sensation in a very formal way, and while more of it manifested in your previous work, in Gifucho there is no sense of that. In that sense, that piece is the least like you of any of them.

Nakahara : For just that moment, I was exhausted.

— But if what you said just now is true, Gifucho is the last work from the period when you were doing this.

Nakahara : I guess so. But it is, in large measure, consciously manipulated. It hasn’t just tumbled out.

Sekiguchi : There’s a sense of it being “placed.”

Nakahara : Exactly. I think that’s connected to the discussion about feeling responsibility.

Sekiguchi : And it’s amazing that offering that up within that whole illustrious context of Japanese art in Antwerp fits perfectly in the story.

— It’s the very last of a current that began with Mono-ha, really. Was that a new work you made because of the specific lineup of artists there?

Nakahara : In terms of the situation, obviously I’d heard it was open-air, and envisaged installing it in those conditions. I was trying to do it as the next step in the current of my own work, and I also displayed the “light worm” – second one I made – and worked on how to step forward from there. So as I mentioned, there is manipulation. I did it because I tried to do it.

◆No conscious link to art history

— Just to be sure, may I ask again: what do you mean by “not taking responsibility” as you were saying earlier?

Nakahara : I mean being irresponsible when it comes to, discarding responsibility for, “context.” Meaning my thoughts after that when I was doing Lego, the figurines and such were still that I’d shelved responsibility for what one might term” my own affairs.” I wanted to take them full on.

All that responsibility I had taken on myself with regard to context, suddenly I thought no, I don’t need any of that. I thought I’d say as much.

Sekiguchi : I imagine many artists reach that point, but whether they do anything about it is another matter entirely…

Nakahara : Did you come to that point?

Sekiguchi : Well….I suppose making works by computer was in a way me trying to take responsibility, compared to you.

Nakahara : Just before resigning (from Kyoto City University of Arts) Koshimizu-san invited Sekine Nobuo to give an intensive course of lectures, and I spoke a little to Sekine-san. He said that indeed, he does think about people in the past and himself following them. I’m totally oblivious to that. Maybe I only think I am, but not only do I mean in the sense of being connected to what’s happened immediately before; I’ve no awareness either of points connecting over long periods of time. Yet, nor did I feel I was actively endeavoring to be that way. At the risk of repeating myself, once I start tumbling, all I can do is keep rolling with it, unable to stop. It can’t be helped.

— How did you feel about responsibility and all that when you took on “Aperto”?

Nakahara : By “Aperto” my whole mindset had changed. So I actually hesitated to accept. To jump back again, to the likes of Yanobe Kenji suddenly emerging at Art Tower Mito (27): I was watching him right up to that point, and it was fascinating. To the extent that I thought if he tried to exist in society in that form, unmodified, the world might actually change. In fact, he and those who followed him worked hard to enter the place I had tried to leave. I think that was the moment we swapped places. But at that time, they weren’t asked to “Aperto,” they weren’t even close. Proof that they were in a dimension totally unrelated to the world symbolized by “Aperto,” a new state. How cool is that, I thought. I was incredibly bogged down with the question of why I’d been placed in the situation of having to think about whether or not to accept the “Aperto” offer, just like one of the old generation. To convince myself, I told myself it was a project, tried to make it about being related to my own real family, strove to come up with a narrative, and by doing so resolve it in my own mind, but half of it was just excuses. I still felt odd about having accepted that commission.

— If I may be very hypothetical here, if for example you were asked to do the Japan Pavilion at the Venice Biennale now, would you accept?

Nakahara : It would never happen, but if it did I would refuse, no question. There’s no common ground there.

— But with “Aperto” even, it was about being told to take responsibility, surely?

Nakahara : Which is why even if I feel that way, physically I haven’t caught up. I have regrets about it, for one thing, and there was an expectation that if the excuses I gave just now panned out, even as a non-professional there could be a different path for me, but ultimately, I find it hugely contradictory. I brooded over it for ages. Though I’m still grateful to those who cooperated with me during that time.

— Did you only get over it much later?

Nakahara : I didn’t so much get over it as gradually, found more and more moments where I was over it. Although compared to back then, I have a lot more going on now.

— I see. Today we’ve learned for the first time, I think, about the circumstances that led to you distancing yourself from the art world. Thank you for sharing with us.

Nakahara : If I might just say, on a final note, the term “distancing oneself” is the interpretation of someone standing still in the same place, or someone concerned about their relationship with that place. In reality, I want to go where I want to go, and being cognizant of how far I might be from art serves no purpose whatsoever. So I would never question myself about that.

November 3, 2013

Kyoto

—

Nakahara Kodai Artist. Born 1961 In Okayama Prefecture. Completed his MFA in 1986 at Kyoto City University of Arts. Spent 1996-1997 in New York on a grant from the Japanese Government Overseas Study Program for Artists provided by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. Currently Professor in the Department of Sculpture, Kyoto City University of Arts.

Sekiguchi Atsuhito Artist. Born 1958 in Tokyo. Completed graduate studies in 1983 at Tokyo University of the Arts. Held posts as Professor and President at IAMAS (International Academy of Media Arts and Sciences). Currently a Specially-appointed Professor at IAMAS and Professor in the Department of Design and Craft at Aichi University of the Arts.

—

| Notes |

1. “Aperto”

A section of the Venice Biennale introduced in 1980 dedicated to exploring emerging art. “Aperto ’93: Emergency/Emergenze,” in which Nakahara participated, was organized by Helena Kontova, directed by Achille Bonito Olivia, and had 13 curators, among whom were Francesco Bonami, Nicolas Bourriaud, and Jeffrey Deitch. The show featured works by 120 artists including Matthew Barney, Maurizio Cattelan, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Damien Hirst, Carsten Höller, Paul McCarthy, Gabriel Orozco, Philippe Parreno, Pipilotti Rist, Kiki Smith, Rudolf Stingel, Rikrit Tiravanija, and many others who would go on to achieve star status.

2. “Anomaly”

A group exhibition held in 1992 at Röentgen Kunst Institut in Omori, Tokyo. Curated by Sawaragi Noi. Participating artists: Ito Gabin, Nakahara Kodai, Murakami Takashi, and Yanobe Kenji. The exhibition was said to symbolize Japanese Neo-pop of the 1990s. Nakahara showed a work featuring an isolation tank, which was strikingly similar to a work that Yanobe had previously shown.

3. Sawaragi Noi

Critic, born 1962. Sometimes curator. Professor at Tama Art University. After graduating in philosophy from the Faculty of Literature at Doshisha University, he joined the editorial department of the art magazine Bijutsu Techo. His first criticism collection Simulationism, published in 1991, foresaw cultural movements of the 1990s and generated considerable controversy. Among his many other books are Japan/Contemporary/Art and World Wars and World Fairs. “Ground Zero Japan,” an exhibition he curated in 1999, advocated a resetting of established values, and featured works by artists including Aida Makoto, Ameya Norimizu, Ohtake Shinro, Okamoto Taro, Odani Motohiko, Murakami Takashi, Yanobe Kenji, Yokoo Tadanori.

4. Murakami Takashi

Artist, born 1962. PhD from Tokyo University of the Arts. Director of the art production company Kaikai Kiki. Known for his works that take subculture such as anime and figures as their subject matter and for promoting the theory of “Superflat.”

http://gallery-kaikaikiki.com/category/artists/takashi_murakami/

5. Yanobe Kenji

Artist, born 1965. MA from Kyoto City University of Arts. Professor at Kyoto University of Art and Design. Based on his experiences and memories of the Osaka Expo, Chernobyl, and the Great Hanshin earthquake, he creates large-scale sculptural works exploring the themes of the ruins of the future, survival, and revival.

http://www.yanobe.com

6. Ito Gabin

Editor and designer, born 1963. Graduated in economics from Seijo University. After editing the PC hobby magazine Login, he has been active in a variety of fields including game software development, editing, writing, producing exhibitions, and an on-demand T shirt project. Professor of design at Joshibi Junior College of Art and Design.

7. IAMAS

Institute of Advanced Media Arts and Science. Established in 2001 in Ogaki, Gifu as a media art school upholding “a fusion of advanced technology and artistic creation” as its founding principle. The International Academy of Media Arts and Science, which was founded in 1996, closed in 2012 and shares its acronym, was in effect its predecessor.

8. that time in Sendai

“Landscape – The Former Island,” a group exhibition planned by the participating artists – Sekiguchi Atsuhito, Nakahara Kodai, Takamine Tadasu – and held in 2005 at Sendai Mediatheque.

9. the ones with stuff stuck on your head

Nakahara’s “Headgear” series of works consisting of helmets and catcher’s masks with parts from plastic models or radio-controlled cars attached to them.

10. Satani Gallery

Art gallery established by Satani Kazuhiko in 1978 in the Kyobashi district of Tokyo, relocating to Ginza in 1982, and to Ogikubo in 2000. Satani Shugo, Kazuhiko’s son, has since taken over the operation and aims of the gallery, which he runs in Kiyosumi as ShugoArts.

11. “Magiciens de la terre”

An exhibition held in Paris in 1989 at the Pompidou Centre and Grande halle de la Villette. Curated by Jean-Hubert Martin to correct the problem of “100 percent of exhibitions ignoring 80 percent of the earth.” Martin selected 100 artists from around the world: half from the so-called “centers” of the world (the United States and Europe) and half from the “margins” (Africa, Latin America, Asia, and Australia), their works including masks and mandalas.

12. Minemura Toshiaki

Art critic, born 1936. Professor Emeritus of Tama Art University, Chairman of AICA (International Association of Art Critics) Japan. Graduated in French literature from the University of Tokyo, thereafter joining the Mainichi Newspapers. Involved in organizing and running the Tokyo Biennale in 1970. Member of the international jury and steering committee for the Paris Biennial from 1971 through 1975. Organized a great many exhibitions including the “Parallel Art” (1981-2005).

13. outdoor sculpture exhibition

An exhibition of Japanese sculpture held in 1989 at the Open-air Museum for Sculpture Middelheim in Antwerp, Belgium to coincide with the 20th Middelheim Biennale and 10th Europalia. In addition to Nakahara, the exhibiting artists included Lee Ufan, Miki Tomio, Sekine Nobuo, Suga Kishio, Koshimizu Susumu, Hikosaka Naoyoshi, Endo Toshikazu, Tsuchiya Kimio, and Aoki Noe. Curated by Minemura Toshiaki.

14. “Open Mind”

“Open Mind (Closed Circuits),” an exhibition held in 1989 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent. In addition to works by early-modern and contemporary masters ranging from Vincent van Gogh and Marc Chagall to Francis Bacon and Jan Fabre, it also featured a number of works by so-called “outsider” artists the likes of Adolf Wölfi. Curated by Jan Hoet.

15. Lee Ufan

Artist, born 1936 in Kyongnam, South Korea. Based in Japan, active internationally. Graduated in philosophy from Nihon University in 1961. Played a central role as the theoretical leader of the Mono-ha movement that emerged in the late 1960s. Professor Emeritus of Tama Art University.

16. Suga Kishio

Artist, born 1944. Graduated in painting from Tama Art University in 1968. Began producing works from the second half of the 1960s as a Mono-ha artist, participating actively in international exhibitions worldwide ever since. His works depict the “state” of things, and through relationships and arrangements study how things exist.

17. Koshimizu Susumu

Artist, born 1944. Retired from his professorship at Kyoto City University of Arts in 2010. Entered the Department of Sculpture at Tama Art University in 1966. Assisted Sekine Nobuo in 1968 in producing Phase – Mother Earth. Presented Paper at the group exhibition “Trends in Contemporary Art” (Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto) in 1969. Counted among the members of Mono-ha.

18. Sekine Nobuo

Artist, born 1942. Visiting Professor at Tama Art University. The history of Mono-ha is often cited as beginning in 1968 with unveiling of Sekine’s Phase – Mother Earth. Between ’68 and ’70, he produced work after work that would spearhead the Mono-ha movement

19. Toya Shigeo

Artist, born 1947. Professor at Musashino Art University. MA in sculpture from Aichi University of the Arts. Participated in the 43rd Venice Biennale in 1988. Known for chainsaw-carved wooden sculptures.

20. Aoki Noe

Artist, born 1958 in Tokyo. Visiting professor at Tama Art University. Received her MA in sculpture from Musashino Art University in 1983. Known for her large-scale iron sculptures, the material she has been working in since the early 1980s.

21. Ensor

James Ensor (1860-1949). Belgian Modernist painter. Known for his distinctive style using masks and skulls as a motif.

22. Magritte

René Magritte (1898-1967). Famed Belgian Surrealist artist. Through uncanny juxtapositions of ordinary elements and other tactics that defamiliarize the familiar, Magritte created enigmatic images that surprise and mystify the viewer.

23. Muramatsu Gallery

Art gallery opened in 1942 in the Ginza district of Tokyo, closing in 2009, that showed the works of important post-war Japanese artists including Domoto Hisao, Lee Ufan and Kikuhata Mokuma.

24. “Post Hobby”

Nakahara Kodai’s solo exhibition held in 1992 at Satani Gallery.

25. Jean-Hubert Martin

Born 1944 in Strasbourg, France. Graduated in art history from Sorbonne University. Served as the director of a series of major European art museums including the Kunsthalle Bern, the Centre Pompidou Musée National d’Art Moderne and the Musée National des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie in Paris and the Museum Kunstpalast in Dusseldorf. Director of the French pavilion for the 2011 Venice Biennale (featuring artist Christian Boltanski).

26. Lyotard

Jean-François Lyotard (1924-1998). French philosopher, who in one of his best-known books, The Postmodern Condition (1979), contended that the post-modern age marked the demise of the “grand narrative.”

27. Yanobe Kenji suddenly emerging at Art Tower Mito

Yanobe Kenji’s solo exhibition “Yanobe Kenji Paranoia Fortress” held at Art Tower Mito in 1992. Taking “survival” as his theme, he created and presented tools for surviving radioactive contamination.

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

(Publication of the English version: 7 April 2014)