Conversations between Nakahara Kodai and Sekiguchi Atsuhito : 1. “KODAI NAKAHARA: Migration or Retrospective” (Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art)

Moderator: Takashima Yuichiro

➔Conversation between Nakahara Kodai and Sekiguchi Atsuhito : 2. In Kyoto

Moderator: Takashima Yuichiro (Curator, Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art)

Since around 1990 Nakahara Kodai, who first came to public attention in the 1980s as a standard-bearer for Kansai New Wave (1) and Japanese Neo-pop (2) – to the extent of being celebrated as a “genius” by some – has steadily drawn a line between himself and the conventional art world. However, an exhibition of drawings in 2012 at the Itami City Museum of Art has since been followed this past autumn by a show at the Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art: the first ever major Nakahara exhibition at a public art museum. What prompted the long silence of this legendary artist? What inspired works such as his Lego and figurine pieces, huge influences on those who came after? Following is the transcript of a dialogue between Nakahara and longtime friend and confidant, artist Sekiguchi Atsuhito, held during Nakahara’s solo show at Okayama.

2013.10.12 / Courtesy Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art

— Since the early 1980s the two of you have exhibited together at every available opportunity, consistently inspiring each other artistically. This includes the 1995 group show “Art Labyrinth” (3) here at the Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art. Today’s dialogue came about when we asked Nakahara-san to take part, and he replied he would like you to join him, Sekiguchi-san. If we could start with you Sekiguchi-san: what is your view on the exhibits here?

Sekiguchi : I’ve seen quite a variety of work by Nakahara Kodai. His output is dominated by really big pieces that home in on topical concerns. There is definitely a sense of that in this show. The bits the audience would usually reject through a lack of understanding instead make one wonder, “Just why is it like this?” I’d have to say though, I get the impression those helping with the exhibits would have found it tough (laughs).

It’s pretty hard to grasp on what basis that sense of volume has made it to this point. It strikes me that you have an image of something big, yet you’re not trying to get it all out in one go. Would that be right?

Nakahara : I’m not sure that it’s directly related, but let me explain a particular episode mentioned in the exhibition pamphlet. As a child, when you learned of dictionaries, I’m sure you looked up all the odd, naughty words like “poo” and “wee” (laughs). In the same vein, on first acquiring a kanji dictionary, you get this urge to look up things like the meaning and etymology of your own name. The first character in my first name is the kanji 浩, that is, “water” combined with tsugeru meaning to communicate or inform, and on looking I found it meant “big with lots of water,” which led me to think of myself as basically “a jolly great mass of water.” I’ve never forgotten that. I always have this image of myself as hard to pin down, as having all this stuff sloshing about inside me. So I suspect the way of thinking and behaving you’ve mentioned are probably pretty much on target.

◆1989: watershed year

Sekiguchi : To me your works of the ’80s hinted at an external form viewed from the inside, something amorphous like you describe, but then you went on to do the opposite: pursue the surface, in a sense, while staying mindful of the content. Was this a conscious decision?

Nakahara : The black and white painted marble piece in this show is from 1989. Broadly speaking this was an end point, of one particular current. I took that piece soon after making it to an exhibition of Japanese contemporary outdoor sculpture in Antwerp (4), but partway through had a change of heart, and for quite a while it didn’t see daylight, not until the show at Korakuen the year before last (5). I took it in ’89, it came back in ’90, then languished in storage until 2011. I’d have to say that things up to that work, and after it, did have a different feel.

Gifucho, 1989, Marble, urethane paint on stones

Photo Nagare Satoshi, courtesy Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art

Sekiguchi : Why the title Gifucho (the butterfly Luehdorfia japonica)?

Nakahara : There was a sculpture Katakuri to gifucho I showed at the same time, the marble being the butterfly, and the bronze the katakuri (dog’s-tooth violet). Originally it came from a photo of such a butterfly hanging off a violet, but obviously the name is another way of describing the substance of the image, not the work in concrete, unmodified terms. So in terms of the difference in substance, that was the “gifucho” part. So I think of it as “gifucho” but actually, it could just as well have ended up “Untitled” (laughs).

Sekiguchi : But surely you were also the artist who never let a particular work see the light of day again? As in, it wouldn’t matter if it disappeared.

Nakahara : I have a storage place in Kurashiki, and most of what’s on display in this show is from there. Gifucho was in there. Three of us were jointly renting a storage-cum-studio sort of facility in Kyoto too, but that burnt down in 2010, reducing almost everything inside to ashes. There were other works as well.

Storage-cum-studio in Wachi, Kyoto / 2010.08.06

Photo Nakahara Kodai

Sekiguchi : Did the other two also lose their work?

Nakahara : Yes. But they kindly saved my pieces that had ended up like this, before turning to their own. This is the marble piece Hikari no mimizu (Light worm), my graduation work.

Storage-cum-studio in Wachi, Kyoto / 2010.08.09

Light worm?, marble

Photo Nakahara Kodai

Sekiguchi : So this is what happens to marble…

Nakahara : Marble is hopeless, really. Once heat gets in it just falls apart. Almost everything else was ruined too, with just a few pieces rescued, in this state. What the fire really brought home to me was how many of my notes, sketchbooks and such were in there. Even the ones that survived were carbonized and I couldn’t peel the pages apart. Initially it didn’t affect me that much emotionally, but it does gradually creep up on you, that sort of thing.

Sekiguchi : Is this a silicon piece?

Nakahara : Plaster. Today I finally managed to get just a section of it preserved and placed in a green plastic case near the entrance to the exhibition space. The rest of it is still being worked on by the cultural property preservation and restoration faculty at Kibi International University. Wondering what to do, I started communicating back and forth with Takashima-san, the curator, who told me about the university, so I began consulting with them on the treatment and care of scorched marble, plaster and so on. Initially I had trouble recalling with any accuracy what had been there and burned, then gradually things started to come to mind, as in “I’m sure that must have been there…” I’d actually pretty much left the Kurashiki storehouse alone too, and hardly been to take a look. So it struck me I should have another dig around and see what was there.

As you say, part of me felt that it wouldn’t matter if it all went. All those models piled in display cases were my collection at the time, purchased anew, but they stayed like that: hardly anything assembled. I’d just buy the stuff and leave it in the box. As long as I had it, it didn’t even seem to matter what was inside.

Storage-cum-studio in Wachi, Kyoto / 2010.08.09

Stuffed toy of Kodai’s descendant, plaster

Photo Nakahara Kodai

Display of plastic models, remake, 1992/2010-13

Photo Nagare Satoshi, courtesy Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art

Sekiguchi : Well, everyone has some idiosyncrasy of that sort. I have about twenty boxes myself.

Nakahara : As long as they’re in your possession; in fact, as long as they’re around somewhere. In a sense it was a case of well, it’s not like we can reproduce things that come about from time to time just by repeating them, so that single moment in time will suffice, but having this fire happen has altered my feelings on that, little by little… To something like OK, let’s start with what we can do. In terms of the models that meant trying to collect the same ones again, buying them in auctions, starting at one end and working my way through.

◆The difficulty of remaking

Sekiguchi : So does this mean your image as an artist changed, in a way? As in, there are two Nakahara Kodais: one who sprinted ahead without a backward glance, doing the most interesting thing in his immediate line of vision, and one taking another look back. Though observing this latest show, I don’t really sense any looking back.

Nakahara : No. I don’t seem to be consciously trying to recap and put things in any kind of order. More like a reaction, without any real reason, to that fact that they’re gone, what to do?

Sekiguchi : So in a good sense, this is not a retrospective at all then (laughs).

Nakahara : It’s the museum that wanted to make it a retrospective (laughs). But I have to say, remaking things is really hard. Finding myself unable to buy stuff that’d been easy to get pretty much anywhere, for a start.

Sekiguchi : Mmm, I suppose it must be tough.

Nakahara : I actually haven’t managed to set about remakingmost of the works that were burnt. The process of remembering all sorts of things, collecting materials and so on is progressing well enough, but I haven’t managed to get as far as remaking, so those works are not in the exhibition. Among what is there are several pieces in which the original survived, albeit somewhat deteriorated, and was used as a reference to make another copy. The original of the piece with the polystyrene dog on top of a radio-controlled vehicle is held by Gallery 16 (6) in Kyoto, and studying the actual thing I realized it had indeed deteriorated quite a bit over the years, so decided to make another one. Setting out to do so, what surprised me most was, take those big marbles I stuck in for eyes, that I just bought at some random toyshop: you can’t get them now. Then there was the collar: those thick black studded ones are not fashionable these days, so I had to search for an end-of-line one online. And so it goes on. One other thing was, I’m sure that for the dog I shaved the polystyrene quite roughly, and completed it in less than a week. Trying to make it again, I find there’s no way I can reproduce that method. It’s hard, actually. I just can’t manage it.

Left: Radio-controlled vehicle 4, 1989-1990

Right: Radio-controlled vehicle 4: Rune, 2011

Radio-controlled vehicle kit, proportional system, expanded polystyrene foam, and other materials

Photo Nagare Satoshi, courtesy Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art

Sekiguchi : Isn’t it a bit like an aging artist reproducing a good work from his youth?

Nakahara : I don’t think so… actually, maybe it is?

Sekiguchi : Close, then (laughs)?

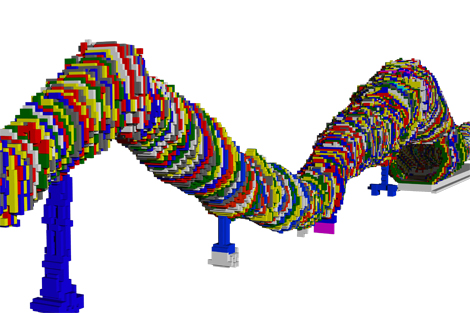

Nakahara : I just can’t imitate the originals. Even that Lego work as you come down the stairs, when you form the Lego into a loop: in the original the number going up and down don’t match (laughs). I imagine I started with the big part, and only noticed later. To hide that, there’s another layer over the top.

Sekiguchi : I think you might’ve told me that just after you made it.

Nakahara : And another thing. I imagine I did this when I first showed that piece at the Heineken (7) in Tokyo, then again for the National Museum of Art, Osaka (8), but when I drew up the plans this time to make it again, the surfaces contacting the floor were all over the place. In desperation, I’ve just dropped about seven steps’ worth right at the end. I imagine that unable to connect straight, it’s been twisted, and finally, I’ve had no choice but to deliberately offset it like that to make it join up. There are loads of quirks in it thanks to that sort of half-baked construction. In the end, I managed to get the number going up and down to match, at least, but to be honest, I couldn’t fix the rest. You can’t beat that randomness. Although initially I actually thought I’d try making it like it is now again, without taking any measurements or such.

Untitled (Lego worm), remake, 2013

Lego, epoxy resin

Photo Nagare Satoshi, courtesy Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art

Untitled (Lego worm), 3D drawing made from original by Nakahara Kodai at the time of the remake

◆Not everything has to be turned into a work of art

Sekiguchi : There’s a worm from a few years back that is similar to this Lego effort, isn’t there? The one that burnt. They’re presumably the same, so is there any connection between them?

Nakahara : Just a form I happen to like, I suppose.

Sekiguchi : As in, slithery, wiggly things?

Nakahara : Mmm. When you make something from stone, for various reasons – money for example – it has to fit within certain dimensions, but if those limitations did not exist, as with Lego, it might end up a different way. But as to that earlier worm and the Lego worm being the same proportions, and whether that was important to me: when I did the Lego worm it was much more about what “using Lego” indicated.

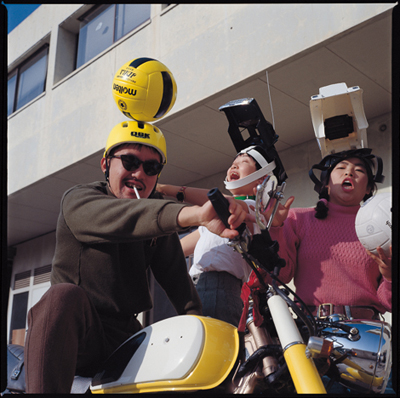

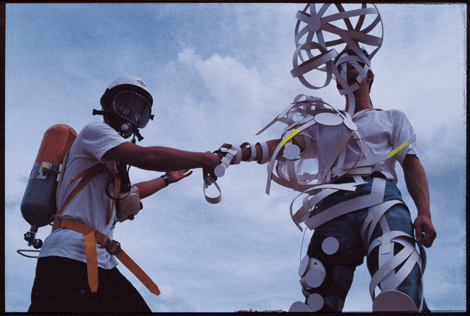

Sekiguchi : By around ’91 you’d started to produce works that involved affixing tools to the head; does this mean you shifted toward wondering how you would sense yourself when wearing them? The idiosyncratic form of those pieces is what catches the eye, but was it more about the condition of the person wearing them, or things like the experiential sensation of them – sitting in a chair, floating in space?

Nakahara : Hmm, I suppose so. I would say though, that there is also this sense of being watched. Sensing someone’s gaze, the feeling of being watched by people.

Sekiguchi : So you prefer to do things yourself, rather than others doing them?

Nakahara : I prefer to deal with my own feelings, rather than those of others, yes.

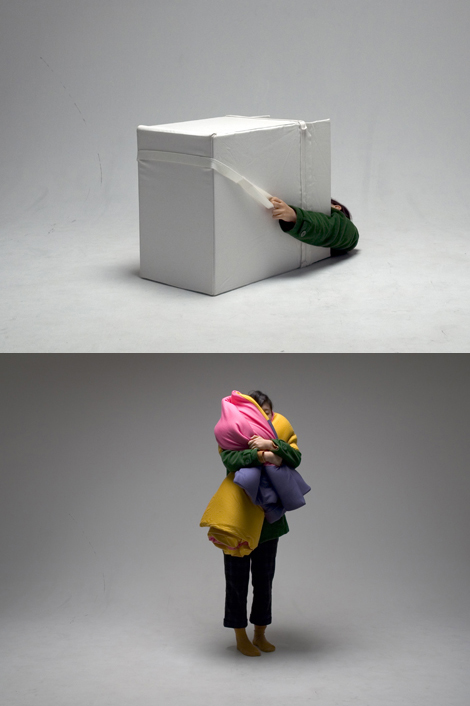

Sekiguchi : You’re also a fan of “containers” aren’t you, like that box you made in collaboration with Inoue Akihiko (9).

Nakahara : Not so much containers perhaps as that sense of touching, contacting.

Sekiguchi : Touching, coming into contact are regional, surely. Is it not more important to enter fully into the whole, to be enveloped?

Nakahara : I don’t actually imagine the sensation of being surrounded very much, and though I know it’s odd to describe it as “Linus’ blanket,” it’s more the fact that something is just there. By sensing that one is touching something, one confirms the sensation of being there. It strikes me that the object of contact, the area or size of the contact, is largely immaterial. Fingertip to fingertip is adequate, and I suspect it wouldn’t change much if my whole body was bound.

Sekiguchi : A lot of your pieces are big and weighty, but what makes them work is the way they partially contact. It’s a contact no constructed object could achieve, almost like a poem fragment. In a sense you are achieving that with a body, with material.

Nakahara : I’m gradually losing my objectivity. In part that’s intentional… I find myself gradually objecting to trying to be objective, if you will. With that feeling comes various ways to respond.

Sekiguchi : But you don’t reject the idea of making things into works?

Nakahara : I just don’t have the slightest desire to turn everything into a piece of art. Producing works of art is tough for the art museum, but tough for me too (laughs). So there’s no way I can imagine making things on the assumption that every time, they’ll be a piece of art. If there hadn’t been a reason, I don’t think I would’ve done this lot either. If, hypothetically, I worked alone at home, and that was sufficiently satisfying, then I guess that would be most straightforward. Once other conditions come into play, all sorts of restrictions arise, as well as issues with labor, finances and so on. So when I don’t have the will to make a thing happen despite all that, I deliberately don’t make that kind of choice, I think. Basically, if I can get away with pottering around at home, I’d rather be doing just that.

Headgear1 (Volleyball) / Headgear2 (Convoy truck)

Headgear4 (Bullhead) (destroyed in fire)

1991, volleyball, helmet, plastic model, leather

Collaborative research between Kyoto City University of Arts and National Space Development Agency of Japan (NASDA; currently JAXA)

AAS – Artistic approach to the universe, 2001-2003

Above: Prototype for “Linus’ blanket,” in environment of microgravity (box-type), 2003

Below: Prototype for “Linus’ blanket,” in environment of microgravity (blanket-type, ver.Nakahara), 2003

◆It’s the realness of a place that seduces

Sekiguchi : When you were working with paper in Shizuoka (10) I thought by following all the processes you’d arrive at some sort of form, but that it wouldn’t be a work. Yet when traces start to appear like they did there, a thing can start to look like a work of art. And when I went to visit you at home, you were using a marker pen to diligently trace the trail of a river snail, and that also emerged as a work. It struck me that the vestiges of things you see in day-to-day living just seem to naturally remain, like they did there.

First Kamiwaza Award, Plaza Oruri (Shimada, Shizuoka), 1991

Nakahara Kodai, wearing his Shimada Suit 2, with Bonbe otoko (Cylinder man) Hibino Katsuhiko

Fish tank, 1995, tracing of a rivers snail’s movements

Nakahara : If it hadn’t emerged as a job to do after the studio burning…that is, the things on display here are not so much placed there as artworks, but brought along as proof, in a way to convince myself, I guess. If not, when it comes to the snail I should be able to just mark its trail at my own home, and stuff I did like repeatedly playing around with ephemeral things that appear only to disappear in Shimada in Shizuoka, is also the sort of thing that is fine to disappear in that instant, in fact in my view that is the purest form. Yet as you say, searching through the warehouse there were lots of all sorts of things in boxes. What is that about, I wonder…?

Sekiguchi : I think interesting artists increasingly go that way, because the distinction between the public and private sides of their lives naturally starts to disappear, and they find themselves exposed.

Nakahara : I don’t like the sound of that at all (laughs). If there’s no reason to disturb me, I’d rather be just left alone.

If I may mention the “Landscape” exhibition (11): round that time, in summer I was going down to the riverbed to photograph swallows, when the idea of doing that group show occurred to me. I then found that my feelings about going to the riverbed changed completely. One starts to get a vision of photographing a thing, compiling it, then arranging it for display. The moment that occurred, something that had been such fun suddenly filled me with guilt (laughs). It’s the realness of a place that seduces you over and over. The realness of chasing something that doesn’t make sense, day in, day out, and still finding you don’t understand it. From those shots, the ones from days where the photos weren’t good are excluded, the ones that look good are chosen, then because there’s only so much space for displaying them the number is prescribed…you have to do all that, and it really hits you that this is far from what you want to do. That was a real struggle for me.

Sekiguchi : If you were to really get serious I suppose you’d have to become a biologist. But there you are, an artist.

Nakahara : Indeed. Not then though (laughs). Going down to the riverbed I came across an ornithology professor, doing surveys and suchlike. He asked me what I was doing, I replied that it was nothing especially scientific, and he gave me a few expert tips. Imagine being an expert on swallow ecology…that’d be great. Maybe I will actually do it.

swl_ujr_040803_01 The riverbed of Uji River – Mukaijima, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto from the series “Swallow“

Photographed 2004.08.03, printed 2005

Sekiguchi : You take an interest in the ecological and concentrate on that, but perhaps what actually feels viscerally real to you is the “state,” would that be right?

Nakahara : It’s not that I’m not attracted to the visual, of course: I have a huge desire to “see.” The thing is, that’s not say, once a month, but repeatedly, day in, day out, the motivation being that feeling of, well, today it was like this, wonder what it’ll be like tomorrow? So I soon end up going the next day. Wondering what it’ll be like for a season, from the start of summer to end of autumn. Miss a day and I feel really uneasy, wondering how that day was. It’s these feelings that take me back to a place every day. Over that particular period, I think I spent more days on the riverbed than the ornithology professor. There are things you see from day to day, but what about the grand overall rhythm? There’s also a sense of being propelled along by that.

In this show there’s a piece consisting of animated graffiti in frames, made in 1995-6, which with any luck people will be able to see in a video booth, but for some reason while I was on the riverbed I was reminded of it. Every frame is rendered randomly, and as an animation plays thirty frames per second. At first glance there appears to be no such thing as a story, which may partly be because the finished piece is so short, but I imagine that if it could be extended, a certain rhythm or flow would emerge, heading out from after the rainy season to autumn of that year, and after an interval, doing the same the following year…I get the feeling it relates to that feeling of how time passes. At one stage I thought I’d like to do a sequel. Later I re-recorded an “A-movie” and a “B-movie” in which the colors change, on DVD.

Sekiguchi : When was this?

Nakahara : I made the DVD version between 2009 and 2011. I did a piece of graffiti on each of those DVDs, and made those into an animation that became the “C-movie.”

A-movie, B-movie / DVD Stack Edition 2009-2011, Drawing on DVD

Courtesy Gallery Nomart

◆Not pinning hopes on ‘mutual understanding’

Sekiguchi : What sort of mood were you in when you did the “fruit graph”?

Nakahara : Well the circumstances of that were, at the first gallery I had them install Donald Judd’s (12) relief Untitled (Progression) (13) on one wall, and placed the “fruit graph” in front of the opposite wall. It was me who requested that work of Judd’s, for some reason it appealed to me in a physiological sort of way. I wanted to position something of my own facing it, and that’s what we ended up with. This is what happened when I tried to do something in a dialogue vein with that work of Judd’s.

Sekiguchi : So what’s with using such perishable material?

Nakahara : Well yes, it does rot… I didn’t especially want to show it decomposing, so I replaced the fruit several times over the period of the exhibition.

Sekiguchi : Judd produces works that create the same moment no matter who sees them, when or where. Do you mean that instead of this, you wanted to show “an instant”?

Fruit graph

Installation view at “KODAI NAKAHARA: Migration or Retrospective”

2013.10.12 Courtesy Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art

Nakahara : The thing is, I wanted to make a statement to the effect that “change is not the process of decaying.” In other words, because an exhibition runs for a certain period, things may have to be replaced several times, but in fact, that instant, that just completed state, may be perfectly adequate. The “thing completed in that moment” I was looking for may be able to be described as complete in that instant. I feel no responsibility for it. The other day you made a comment along the lines of painting having to “pass on everything in a moment,” and that really resonated with me. Yet I feel that I, personally, don’t have that obligation. I can draw an image of being present with “a moment” or “more variable time.” But it struck me that perhaps I don’t have the idea of understanding an image at a glance, that all information is emitted from there. What does it mean to convey something in an instant?

Sekiguchi : I guess it’s because I started with painting. When you paint, you strive to see to what extent you can propagate the same value across the whole of the canvas at once, which if you take it to its logical conclusion, means conveying all the information in an instant. But I don’t sense that sort of thing in you, nor do I think you’d be better off that way.

Nakahara : You paint and you also work in different media: is it the same?

Sekiguchi : No, but even in the likes of installations and media interactions using video, it does come out at times. Not always intentionally, I might add.

Nakahara : Perhaps there’s no need to tie it in with the features of the medium, but I can’t recall having that feeling myself. I don’t think I can, because I don’t see in myself any sense of generating information accurately to start with. I mean, I don’t think I have the ability for mutual understanding, so I don’t have any great expectations in that area.

Sekiguchi : There are people who interpret things their own way, depending on the work.

Nakahara : Fundamentally that doesn’t bother me.

Sekiguchi : I’m sure you’ve had all sorts of things said to you?

Nakahara : You mean with the figurines, Lego and such? When I was doing that I had a fair bit of “Go play by yourself then.” And the symbolism of it, what it meant, that sort of thing. Although in reality I never made anything in response to that.

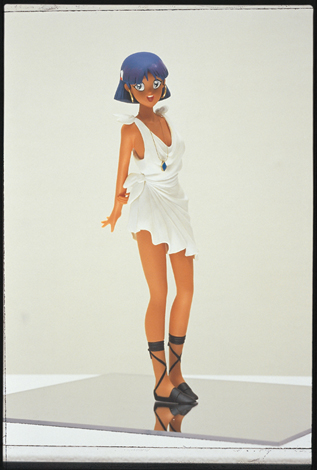

When I was about thirty, I had this urge to remind myself of what a lunar module looked like, and went to a model shop for the first time in ages. All they had though was space shuttles, so I set off on a trek around the shops. Along the way, in a showcase in one shop, I found a tiled bathtub built on a cheap-looking acrylic mirror, with Lum-chan (14) taking a shower (laughs). It was a bit creepy, you know, immature, dumb. I was quite disturbed by it. As I was thinking “Ewwhh, what’s this?” I was informed that it was a “Lolicon” figurine garage kit, a soft vinyl kit for making a two-dimensional anime character. But I couldn’t bring myself to get it. I was too embarrassed to buy it. Then on another day, I got friends, my students to stand behind me so I couldn’t escape, took a deep breath, and bought it.

Sekiguchi : I wonder what your friends thought of that?

Nakahara : Weeelll…who knows (laughs)? That lot were helping me look for “space stuff,” and I think they quite enjoyed doing that sort of thing. In the evening, as soon as they finished work at the university, they’d dash off. “Couldn’t find it here either” “Found that here” “OK I’ll take three then”… They’d order things on the way home. But I just couldn’t bring myself to get that kit. Morally I’ve no problems buying an Ultraman monster, but buying a doll with its skirt flicked up: another matter entirely (laughs).

Nadia, 1991-1992

Color on soft vinyl figure-model

Private Collection. Photo Narita Hiroshi

◆No action without appetite

Sekiguchi : In the end, you produce the thing you want most right now, or thing you want to do. That’s what you’ve always been like. Even if you go through a period of hardly showing anything, you’re still beavering away behind the scenes. What I find amazing is how you can then put that stuff out in such a straightforward, drama-free manner.

Nakahara : Conversely, without that appetite I don’t think I can do anything.

Sekiguchi : So you don’t get motivated without it?

Nakahara : I don’t think so. That’s what it means to have a pile of half-finished projects. Of course, I’ll probably notice at some point that they’ve disappeared (laughs).

Sekiguchi : I’m sure some people say to you, “This work is interesting, why don’t you persist with it?”

Nakahara : I get the opposite as well. “You’ve messed up a perfectly good piece again haven’t you? What’s that about?”

October 12, 2013 at the Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art

—

Nakahara Kodai Artist. Born 1961 In Okayama Prefecture. Completed his MFA in 1986 at Kyoto City University of Arts. Spent 1996-1997 in New York on a grant from the Japanese Government Overseas Study Program for Artists provided by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. Currently Professor in the Department of Sculpture, Kyoto City University of Arts.

Sekiguchi Atsuhito Artist. Born 1958 in Tokyo. Completed graduate studies in 1983 at Tokyo University of the Arts. Held posts as Professor and President at IAMAS (International Academy of Media Arts and Sciences). Currently a Specially-appointed Professor at IAMAS and Professor in the Department of Design and Craft at Aichi University of the Arts.

—

| Notes |

1. Kansai New Wave

A group of young artists – including Morimura Yasumasa, Tsubaki Noboru, Ishihara Tomoaki, Matsui Chie, Sugiyama Tomoko, and Complesso Plastico (Matsukage Hiroyuki + Hirano Jiro) – who came to the fore in the Kyoto-Osaka-Kobe area in the 1980s. On the whole their work was characterized by bold colors and forms, but varied widely, of course, in style.

2. Japanese Neo-pop

Influenced by Pop Art, Neo-pop was an art movement that emerged in the 1980s, best represented by the artist Jeff Koons. In Japan, the March 1992 issue of the art magazine Bijutsu Techo, under the editorial direction of Kusumi Kiyoshi, published a round-table discussion among the three artists Nakahara Kodai, Murakami Takashi, and Yanobe Kenji as part of a special feature titled “Pop/Neo-pop.” The feature also carried a “proposal” that called for “Assembling, for the sake of art, the values of all sorts of otaku, and trying to control this giant construction through the methodology and philosophy of contemporary art. This would become our ‘art of consumer desire’.”

3. “Art Labyrinth”

“Art Labyrinth: A viewpoint to Japanese Contemporary Art.” Participating artists, in addition to Nakahara and Sekiguchi: Kawaguchi Yoichiro, Complesso Plastico, Fukuda Miran, Fujimoto Yukio, Mikami Seiko, Yanagi Yukinori, and Yanobe Kenji.

4. Exhibition of Japanese contemporary outdoor sculpture in Antwerp

An exhibition of Japanese sculpture held at the Open-air Museum for Sculpture Middelheim, Antwerp in 1989 for the 20th Middelheim Biennale – Europalia ’89 Japan in Belgium. Artists, along with Nakahara, included Lee Ufan, Miki Tomio, Sekine Nobuo, Suga Kishio, Koshimizu Susumu, Hikosaka Naoyoshi, Toya Shigeo, Endo Toshikatsu, Tsuchiya Kimio, and Aoki Noe.

5. Korakuen

An exhibition linking art and nature held in 2001 at the Korakuen garden in Okayama as a pre-event to the “Okayama Geijutsu Kairo (Okayama Art Corridor) festival. Artists, along with Nakahara, included Sudo Yoshihiro and Tomii Motohiro.

6. Gallery 16

A contemporary art gallery in Kyoto launched in 1962. <http://www.art16.net>

7. Heineken

Heineken Village. A gallery run by the beer company from the second half of the 1980s through the early 1990s.

8. …then again for the National Museum of Art, Osaka

For the exhibition “Centrifugal sculpture” held in 1992.

9. Inoue Akihiko

Artist and designer born in 1955. Professor at Kyoto City University of Arts. collaborated with Nakahara projects such as KCUA’s “Artistic Approach to Space” project conducted in cooperation with the National Space Development Agency of Japan (currently the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency).

10. …working with paper in Shizuoka

An art project for the 1st Kamiwaza Competition held in Shimada, Shizuoka in 1991.

11. “Landscape – The Former Island”

A group exhibition held at Sendai Mediatheque in 2005, planned and featuring works by Sekiguchi Atsuhito, Nakahara Kodai and Takamine Tadasu.

12. Donald Judd

American artist, born 1928. Best known for the box-like sculptures he called the “specific object,” his work placed him at the forefront of the Minimalist Art movement. Died in 1994.

13. Untitled (Progression)

A series of sculptures that Judd began in the 1960s. To a long horizontal bar or tube are affixed multiple boxes whose lengths and spaces between are ordered arithmetically, e.g., doubling as in the sequence 1, 2, 4, 8, 16; or joined in an inverse series of natural numbers (1-1/2 + 1/3-1/4 + 1/5-1/6…); or based on the Fibonacci sequence (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8…) and so on.

14. Lum-chan

The protagonist (heroine) in Takahashi Rumiko’s manga Urusei Yatsura.

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)

(Publication of the English version: 7 April 2014)