AiR Report

Everything is in transition – in memory’s ephemerality

By Toda Itsuki

Located in the district of Nong Pho in Thailand’s Ratchaburi province, Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts & Culture (hereafter Baan Noorg) is a non-profit, artist-run initiative founded in 2011 by the artist duo jiandyin.

Baan Noorg’s activities are wide-ranging and aim to improve the sustainability of local communities through education programs and workshops.

At documenta fifteen, Baan Noorg presented Churning Milk: the Ritual of Things (2022), a project in Kassel that involved creating a skateboard halfpipe that anyone could use freely. In the project, aspects of Nong Pho’s history, including how a sharp fall in the price of rice in 1968 forced farmers to switch from rice cultivation to dairy farming as their main source of income, Thai traditional shadow puppetry (nang yai), and Kassel’s youth culture were complexly intertwined. A number of media organizations, including those in Japan, reported on the project, so many people have probably seen Baan Noorg’s work.

Baan Noorg also runs a residency space and studio and welcomes artists from around the world. Invited artists can create works and hold workshops while interacting with the local community in Nong Pho for between three weeks and three months.

Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts & Culture / Photo by Toda Itsuki

Welcoming this writer, who was feeling disoriented on their first overseas trip, after the one-and-a-half-hour journey by car from Bangkok, were members of Baan Noorg along with Holly, a curatorial intern from the National School of Fine Arts at the Villa Arson (Nice, France) and Heejung and Insane, two Korean artists who had already begun their AiR program.

My residency was somewhat irregular in that normally the stays of different artists do not overlap. Baan Noorg members were very busy making preparations for Heejung and Insane’s exhibition. The pair were using the residency space until April 14, which meant I had to lay out bedding and sleep on the second floor of the shared space. At first I felt dissatisfied with this treatment, but I ended up treasuring the time I spent together with Heejung and Insane, and as the time for their return home approached I felt sad at the thought of their leaving.

Following the completion of Heejung and Insane’s residency, meetings about my program were held regularly, with Tao and Yow, interns from Thailand’s elite Silpakorn University, also in attendance. We all ate fruit and drank beer at these meetings, and if the discussions grew heated they often turned into marathons lasting more than four hours. Because my work basically depends on the architectural features of the exhibition space I am given, I begin planning for the work after the exhibition location is finalized. However, from the perspective of Baan Noorg, who expect some kind of community-based output, the creating should be centered not on the situation in which the work is placed, but on the history of the location and collaboration with the people living there. Almost all the elements of the work are inevitably determined by means of research that verges on the meticulous. So my process, which for them could have been regarded as passive, was probably hard to understand, and coupled with the language barrier, the disharmony that arose from this weighed heavily on me.

I chose as my venue a small museum called the Tai Yuan Culture Center, where historical materials related to the Northern Thai people, or Tai Yuan, who settled in the area more than 200 years ago are displayed. The facility had previously been used as a medical center and feed warehouse, and still contained items that offered glimpses of what it would once have looked like. When I first went to look at it, the countless pieces of graffiti and traces of adhesive tape on the walls and the discoloration from the sun caught my attention. Having visited a number of museums during my stay, I felt there were sufficient documentary records and artifacts introducing the history of the local area, and my thoughts turned to the things that had been lost in the process of preserving these records and artifacts, and to their traces. I created two prints using magenta and yellow, two colors from the CMYK color model used in printing that are strongly affected by ultraviolet light, and displayed them facing the space’s windows. As they were exposed to the sunlight, the works gradually deteriorated, eventually losing their color completely. The monochrome color fields evoke forms of expression that distance themselves from object and subject, as typified by abstract expressionism, while the fading gives rise to figure-ground relationships on the picture planes, leading the viewer to find meaning in the images that appear there. In addition to this, I walked around houses and stores in Baan Noorg and obtained various objects from local residents on the condition that they were “things they were thinking of throwing away or familiar things they were indifferent to.” In contrast to the print works, in which I paradoxically tried to highlight the existence of things through their absence, my aim here was to once again turn a spotlight on existence that had become absent from the residents’ awareness. I purposely did not make reference to any episodes regarding the objects, some of which are due to be donated to the neighboring hospital and other places. During the opening reception, Gridthiya Gaweewong, artistic director of the Thailand Biennale Chiang Rai 2023, and others visited the venue, providing the opportunity for an informative exchange of ideas.

Artist-in-Residence Exhibition / Photo by Toda Itsuki

On April 26, when my residency was entering its final stage, I accompanied members of Baan Noorg to the Thailand Biennale Chiang Rai 2023 in Chiang Rai, where they were due to take part in the closing ceremony and dismantle their work.

This was the third edition of the Thailand Biennale, which has been held biennially since 2018. What makes this festival unique is that the location changes each time. The first was held in Krabi province, the second in Korat province and the third in Chiang Rai province. Tokyo Art Beat and other Japanese media have published detailed reports of the biennale, so I encourage readers to check them out.

The 2023 biennale was broadly divided between two sites: the Chiang Rai downtown area and the Chiang Saen district.

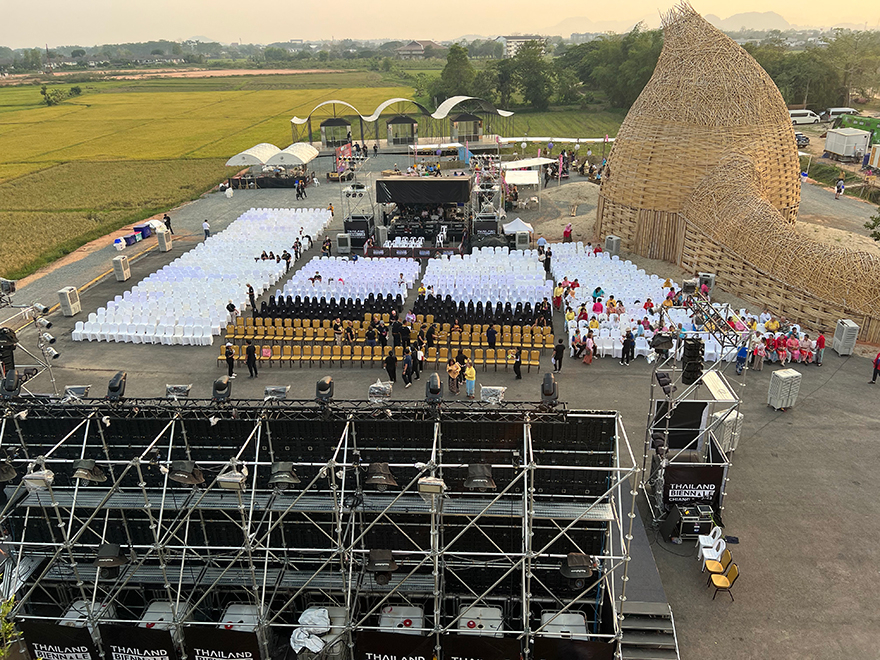

The main venue in the Chiang Rai downtown area was the Chiang Rai International Art Museum (CIAM), which was newly constructed to coincide with the festival. Here, works by internationally renowned artists such as Pierre Huyghe and Haegue Yang were displayed. From the museum’s roof, one could look out over a vast rural landscape, and with the huge LED signage and countless seats for the closing ceremony and various stalls set up on the ground below, a celebratory mood hung over the entire venue.

Chiang Rai International Art Museum (CIAM)/ Photo by Toda Itsuki

The Chiang Saen district, which is even further north than downtown Chiang Rai, borders Myanmar and Laos and is commonly known as the Golden Triangle. Opium poppies were once grown widely in this area, which was the largest opium-producing region in the world. At Chiang Saen, Hsu Chia-wei and Ho Tzu Nyen presented new works focusing on the history of the opium trade in Southeast Asia. Baan Noorg exhibited an inflatable stupa at the site of an abandoned temple. A replica of a stupa destroyed in the 19th century by the armies of Burma and Siam, the inflatable had a blower that directed air inside and was set up to stop at intervals. The way the stupa repeatedly inflated and deflated told of the migration and resurgence of the Tai Yuan, who were expelled from Chiang Saen and forcibly moved to Nong Pho.

Migration has existed throughout human history. During the state of emergency triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, in response to a statement by the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben, Kokubun Koichiro commented, “Freedom of movement is at the root of every freedom.” [*1] The restrictions on the freedom of movement due to COVID-19 imposed on us an inescapable feeling of entrapment. As well, in Japan, with the revision of the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act in 2023, the public is becoming increasingly interested in issues concerning immigration/refugees. Due to rapid advances in technology, we are on the verge of being able to travel anywhere with ease. At the same time, we need to turn our attention to the existence of people who cannot go anywhere even if they want to, and people who are forced to undertake unwanted migration. Having experienced the roots of the multi-ethnic country of Thailand, this is something I have come to sense strongly.

[*1] Kokubun Koichiro, “The Corona Disaster and World Philosophers: The Question of Giorgio Agamben,” Trends in Science, Vol. 26 (2021), No. 12.Toda Itsuki

Artist. born in 1999 in Osaka. Graduated from Kyoto University of Arts, Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Mixed Media Course.