AIR and Me

Part 1: Sapporo as art studio—since “Ripple Across the Water ’95”

By Shibata Hisashi

The beginning of AIR and Me

Quite a long time has passed since I first became involved in artist-in-residence (AIR) programs in the regional city of Sapporo. Without my realizing it, I seem to have now become one of the longest-serving members operating an AIR program in Japan.

What does AIR mean to me? Having been given the opportunity to write about this topic, I would like to share over several articles some of its appeal (or magical powers).

In this first instalment, I would like to discuss the situation “on the eve of” the launch of the 1997 Artist-in-Residence program funded by the Agency for Cultural Affairs. This is also the story of the moment when by good fortune I was able to meet “the person I most wanted to meet in the world.”

Ripple Across the Water ’95

“Ripple Across the Water ’95” was a large-scale international art project staged 30 years ago involving locations all over Japan, with WATARI-UM, the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, in Tokyo handling most of the planning (an exhibition with the same title was apparently also held in 2021 [*1]). With Jan Hoet [*2], a curator with charismatic popularity at the time, as general director, it took the form of an international art exhibition featuring 47 artists (42 from overseas and five selected artists from Japan) exhibiting works at more than 30 locations in and around Tokyo’s Aoyama district for around a month in the summer of 1995. [*3]

Let me make it clear in advance that as far as I can remember, the “Ripple Across the Water ’95” exhibition was not discussed in the context of artist-in-residence programs. This is partly because artists were staying and creating work for an exhibition in Tokyo, so in most cases their stay was brief, and because the term “artist-in-residence” had yet to gain currency in Japan. However, having recently had the opportunity to meet people involved in the exhibition, I learned that like me, some of them went on to launch AIR programs. I recognized anew that it was an art project that led to regional AIR programs in Japan today.

The image behind the title “Ripple Across the Water” seems to have been of “a single drop of art causing ripples that spread to the regions and society around it.” The movement to “socialize art” to which the actions of this drop and these ripples were compared was not simply a poetic concept in the form of a metaphor. The main venue for the exhibition was the area in and around Aoyama where WATARI-UM is located, but in addition to Tokyo, participating artists were selected to create work in seven regional areas: Sapporo, Sendai, Noto, Tsurugi, Okue, Nagasaki, and Minamata. This exhibition, which originated in a particular art museum in Tokyo, had the ambitious goal of expanding into and involving areas all over Japan.

It appears this idea of staging a project in the regions stemmed from Jan Hoet having been pleased with “Jan Hoet in Tsurugi” (1991, 1994), which involved WATARI-UM inviting him to Tsurugi in Ishikawa Prefecture, where there are many traditional Japanese houses, and exhibiting contemporary art in these buildings, as well as to it attracting media attention.

[*1] “Ripple Across the Water 2021.” Organized by WATARI-UM, the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art, and staged across 27 locations in and around Tokyo’s Aoyama district. However, unlike “Ripple Across the Water ’95,” there was apparently no widespread participation by regional communities.[*2] (1936–2014). Founding director of SMAK (the Municipal Museum for Contemporary Art) in Ghent, Belgium. Artistic director of Documenta IX. Often introduced in the media as a “curator” or “freelance curator.” (Around that time, institutions like the Watari-Um Museum in Tokyo were beginning to highlight the role of the “curator,” featuring figures such as Harald Szeemann) As the Japanese word for “curator,” gakugeiin, did not at the time fit the image of someone like Hoet who went out into the city and planned exhibitions, in Japan he was introduced using the English word, as like a new professional. I think it was around this same time that the occupation “curator” gained currency in Japan.

[*3] Numbers for participating artists and exhibition locations are taken from the exhibition catalogue. Some sources give different numbers.

Jan Hoet

On September 27, 1994, I was right next to the person I most wanted to meet in the world.

Around 20–30 local urban development and art insiders were gathered at a restaurant in Sapporo Factory, the venue for “A meeting to talk with Jan Hoet.” As the person most knowledgeable about the day’s guest, I was hastily chosen to be the moderator.

Friendly and approachable like a simple school teacher (he was a former high school teacher) before his address, Hoet began chain smoking and the look in his eyes grew intense when the discussion about art livened up. He was like a wild animal pacing back and forth inside a cage. His distinctive husky voice clearly had an excited tone. I understood that talk of him speaking for three or even four hours about a single slide if allowed to was not just rumor.

“Alle macht aan de kunst / All power to art.” [*4]

Hoet made these words his slogan. He was madly passionate about art, and this passion attracted even people with no interest in the subject.

He’s just like a shaman, I thought. This person gets high while speaking, and it is in that state that he emits his most captivating phrases. The audience strains their ears to hear the next phrase… Jan Hoet had a kind of charismatic aura.

An edited version of “Subete no chikara o ato no tame ni” (All power to art), an article I wrote for Bijutsu Open 84 (1994)

At the time, there were various movements devoted to taking artworks outdoors and turning cities into art museums, and Jan Hoet was involved in the “Chambres d’Amis” exhibition (1986) and Documenta IX (1992) among other initiatives.

While working as a gallerist in Sapporo, I was also in the position of receiving in a regional part of Japan the energy from the above-mentioned “ripples” as a member of the secretariat of the reception organization Kita no Daichi 21 / Art Frontier (director: Nishimura Hideki). Given that I had once aspired to become an artist and had just made the shift to the planning side of things via teaching, Jan Hoet, who had a similar background and had reached the summit of direction (artistic director of Documenta), was someone I revered. In fact, two years earlier, I had travelled all the way to Germany to see Documenta IX, which Hoet had curated, so for the person I most admired in the world to suddenly be heading my way from overseas was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

Here, let me touch on the significance of the “Ripple Across the Water ’95” project as viewed from the regions, something that has not been talked about very much.

[*4] The original phrase is in Flemish (Dutch): “Alle macht aan de kunst”. It was used by Jan Hoet as a slogan to emphasize the significance and autonomy of art. (Information provided by Minato Nanao)From the regions to Tokyo

“Ripple Across the Water ’95” was a project that made people reconsider not only the relationship between “art and society,” but also the relationship between “Tokyo and the regions” in Japan. At the time there was nothing resembling the later boom in international art fairs in provincial Japan. Viewed from the regions, the capital of Tokyo was the absolute center from which all things cultural were transmitted. This “transmission-reception” relationship always had dependent, “unilateral” vectors, including in terms of economic and other political matters.

However, what was unique about “Ripple Across the Water ’95” was that vectors in the opposite direction from “the regions to Tokyo” were actually in effect. While it had been decided in advance that Tokyo was the place where the works would be exhibited, the artists who made the regions their studios ended up living in the new locations assigned to them and also encountered regional resources and mingled with local people. Reverse vectors appeared in the sense that for these artists, the places where they were inspired and where their works came into being were actually the regions, with this made use of in Tokyo where their works were exhibited. (There were cases where works that could be viewed in regional venues could not be shown in Tokyo due to permission-related issues.)

This structure also affected the funding side of things. While I am not familiar with things in other regions that accepted artists, in Sapporo we not only provided human support to the artists, but also bore the artists’ share of accommodation expenses, materials expenses and the cost of transporting their works to Tokyo. In other words, “Ripple Across the Water ’95” was also an art project that only came together due to the financial participation of the regions.

However, in order to raise funds in the regions, having “contemporary art” as a theme was still regarded as problematic. For this reason, as well as necessarily connecting it with the revitalization of towns, the charismatic appeal of Jan Hoet was absolutely essential. His very movement in repeatedly coming and going between Tokyo and the provinces that served as bases was the movement of “ripples across the water.”

Kita no Daichi 21 / Art Frontier, the reception organization in Sapporo, eventually grew to have an executive committee of 180 people. In the six months from the fall of 1994 to the summer preceding the exhibition the following year, we received three visits from Jan Hoet, ran multiple programs aimed at people of various ages from children to adults (see photo below) and hosted talks the largest of which attracted 380 participants. In those six months I personally had the opportunity to moderate five small-scale talks.

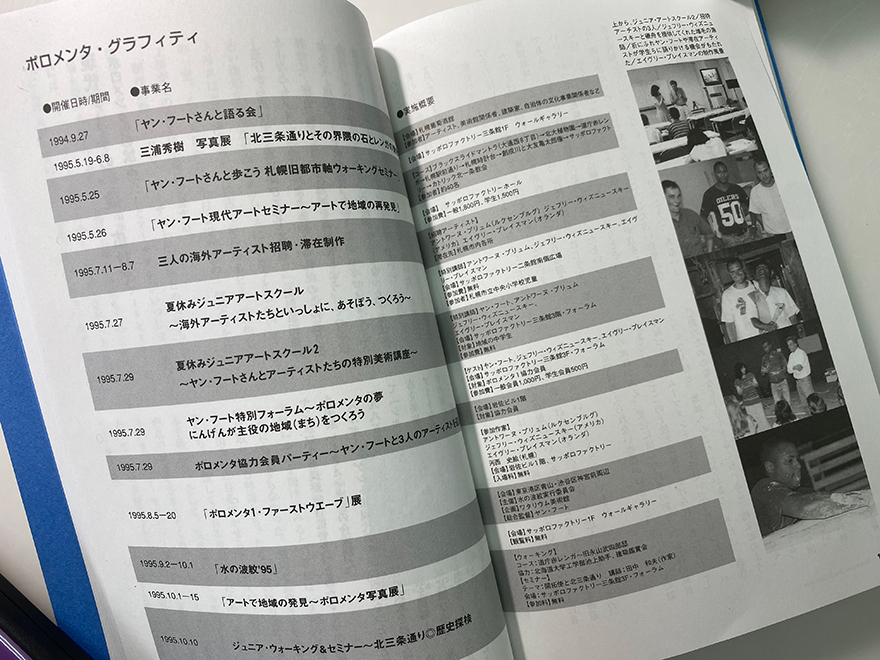

The line-up of events in Sapporo, including a lecture by Jan Hoet for elementary school students. “Poromenta,” a coined word combining the “poro” of Sapporo and the “menta” of Documenta, was used as the project title in Sapporo only. From Bakku mira: Nishimura Hideki ikoshu (Back mirror: A collection of posthumous writings by Nishimura Hideki), 2004, Nishimura Hideki Ikoshu Kankokai.

In the course of my involvement in this art project linking Tokyo and the regions, there is something I discovered as a resident of Sapporo. By this I am referring to the fact that there is a cultural facility that is easier to secure in the regions than it is in the capital of Tokyo, and that is a studio. As well, on the practical side of life, food is tastier, prices are lower, the scenery is better and there is more time to spare.

Though they cannot match major cities when it comes to exhibition spaces and business, when it comes to studios, lifestyle and other aspects of the creative environment, I think the provinces in fact have the edge.

It was this realization that later became the actual impetus behind my decision to quit the gallery in Sapporo and shift to a lifestyle centered on AIR. And today, 30 years later, I still think this decision was the right one.

Before long, AIR programs spread in Japan, but unlike other cultural programs, they did so first from the regions rather than from the capital of Tokyo.

(To be continued)

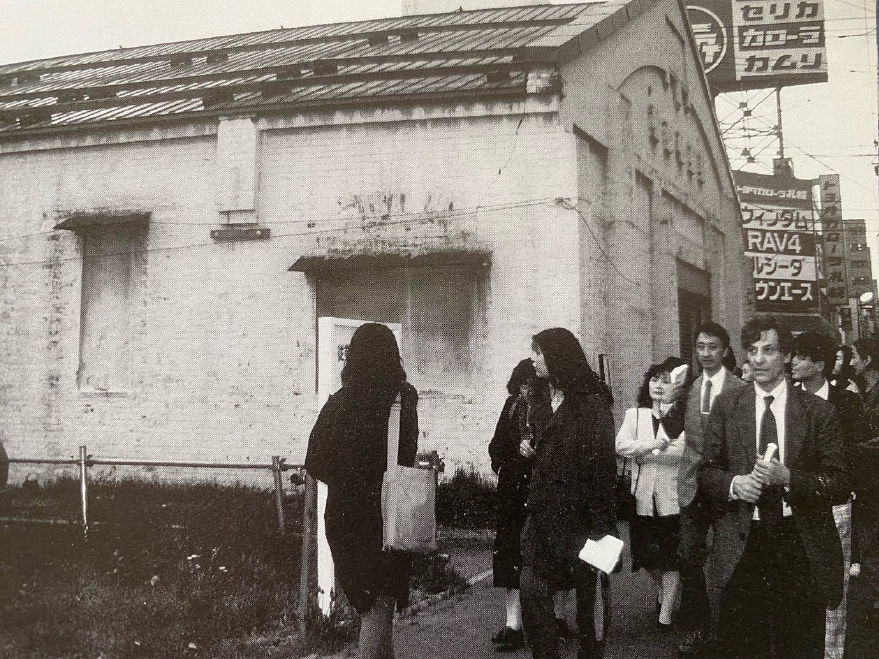

Jan Hoet’s walking seminar, in front of the Hokuren warehouse on Kita Sanjo-dori, Sapporo, May 25, 1995. From Bakku mira: Nishimura Hideki ikoshu, 2004, Nishimura Hideki Ikoshu Kankokai.

Shibata Hisashi

Director, NPO S-AIR / Director, AIR network Japan

Professor, Art Project Lab, Hokkaido University of Education, Iwamizawa

Shibata established Sapporo Artist in Residence (S-AIR) in 1999, which was registered as a non-profit organization in 2005, and awarded the Japan Foundation Prize for Global Citizenship in 2008. To date, S-AIR has hosted 106 international artists from 37 countries and regions, and sent 24 groups of Japanese artists to 14 countries for art residencies. Became a professor in 2014 at Hokkaido University of Education, Iwamizawa, where he heads the Art Project Lab. Co-author of What will change with the designated manager system? (Suiyosha), Basic research into the promotion of regional culture through art and cultural facilities utilizing abandoned schools (Kyodo Bunkasha), and Artist in Residence – The potential to connect towns, people, and art (Bigaku Shuppan).