Cultural Currency 38

Tatsuki Masaru: “Mama” @ Gallery Side 2|Joiners of pieces

By Shimizu Minoru

A photograph is a fragment of the world, yet unable to state unequivocally of what exactly it is a fragment. Defenseless against words, yet at the same time utterly neutral with regard to words of any kind. Affixing the caption “Former execution ground” to an unremarkable landscape shot, for example, or commenting on a quotidian portrait, “In the final stages of cancer” doubtless has considerable influence on how we view the photograph in question. With no change however to the photograph itself. A photograph is never colored by words; never the tool of some garrulous teller of tales. Yet details in a photo may excite the viewer’s knowledge or experience, inducing a memory, association, or fragmented narrative. Joining many photographs, many pieces, can at the least comfortably hint at a “whole” existing before the fragmentation occurred.

This exhibition has an accompanying photobook of the same title—Mama. The artist’s text for his book gives a definitive meaning to the photos therein, as a whole; serving as an answer for the whole, so to speak.1 Is it not possible, one wonders, to obtain that “answer” comfortably from the photographic works themselves?

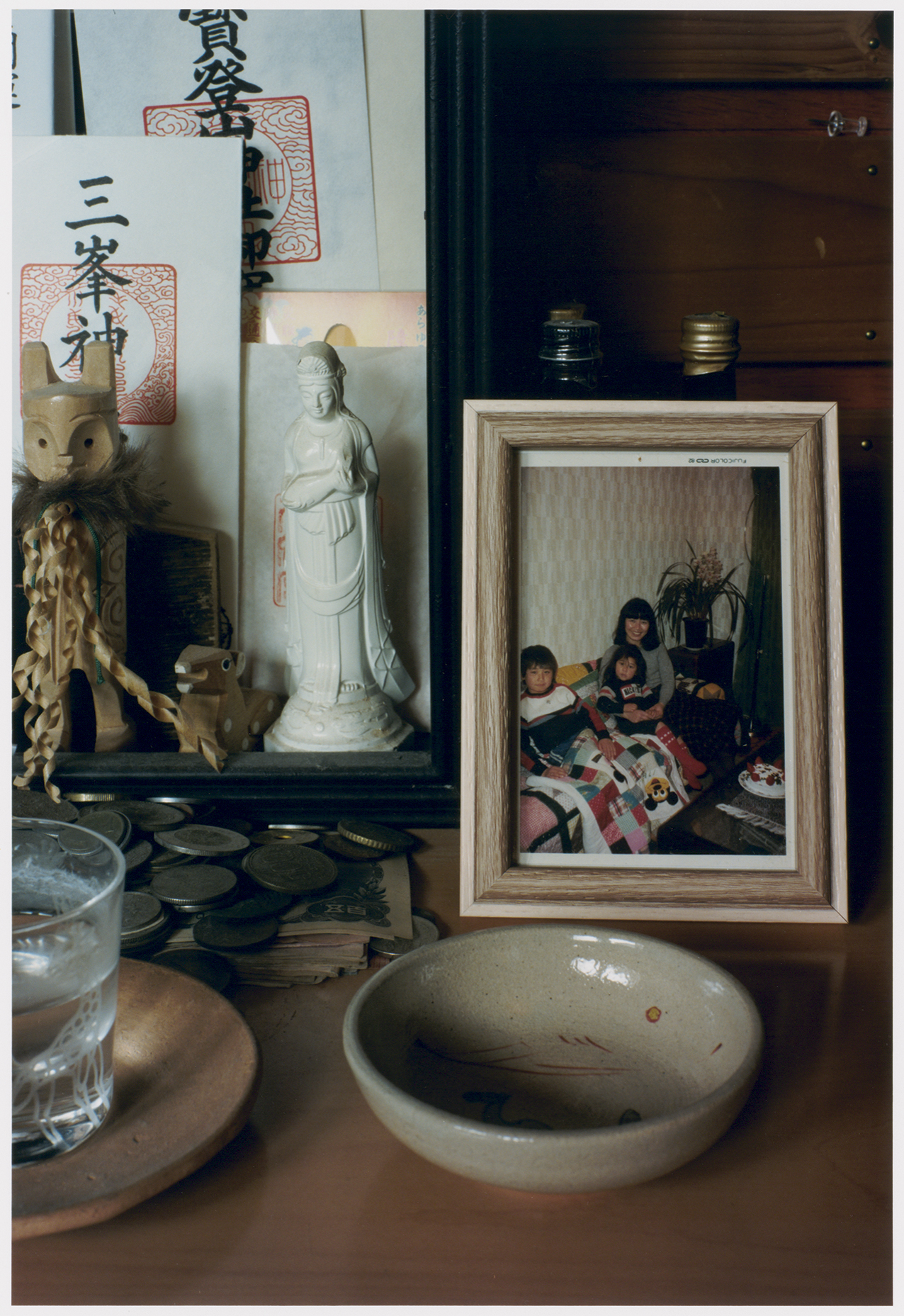

Mama opens to the left from the colophon. The cover photo shows a Buddhist altar of the type found in many Japanese homes, clarifying from the outset that this is a collection of photos taken in mourning and remembrance for the deceased “Mama.” On the altar is a family snapshot of a mother, brother and sister, the age of the siblings indicating that the “Mama” of the title was a word spoken by these children. This family snapshot of wife and children was probably taken by a “Papa.” “Papa” has positioned Mama in the center of the vertically-oriented frame, and also inserted a cake (a birthday cake? Judging by the number of strawberries, a sixth birthday perhaps) on the coffee table, leaving the older brother on the sofa cut off at the left-hand corner. The complete absence of this “Papa” from the photobook is the first mystery.

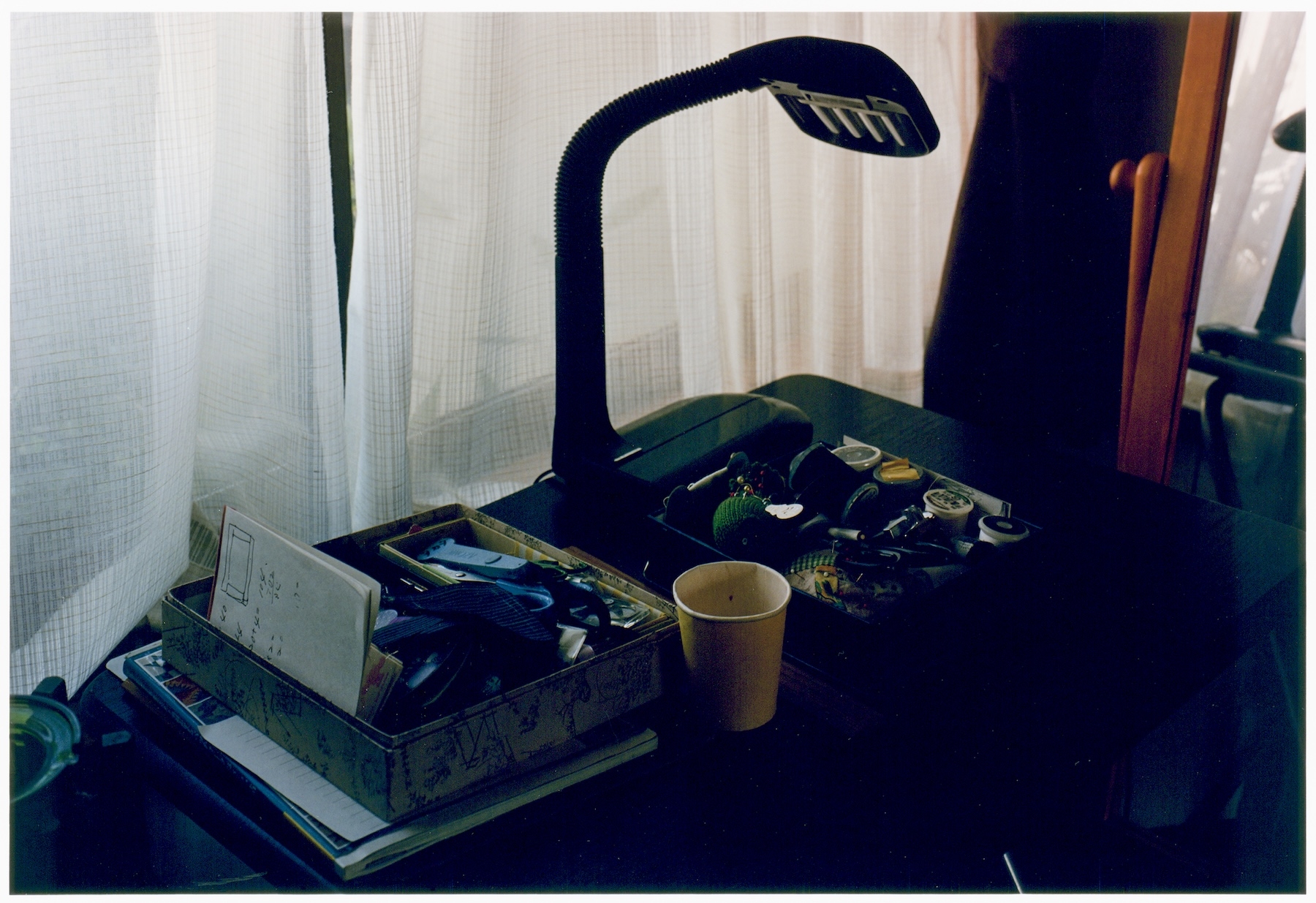

Tatsuki Masaru, Sewing Box, 2025, photographed April 2024, Toyama

Tatsuki Masaru, Bed Cover (Detail), 2025, photographed February 2024, Saitama

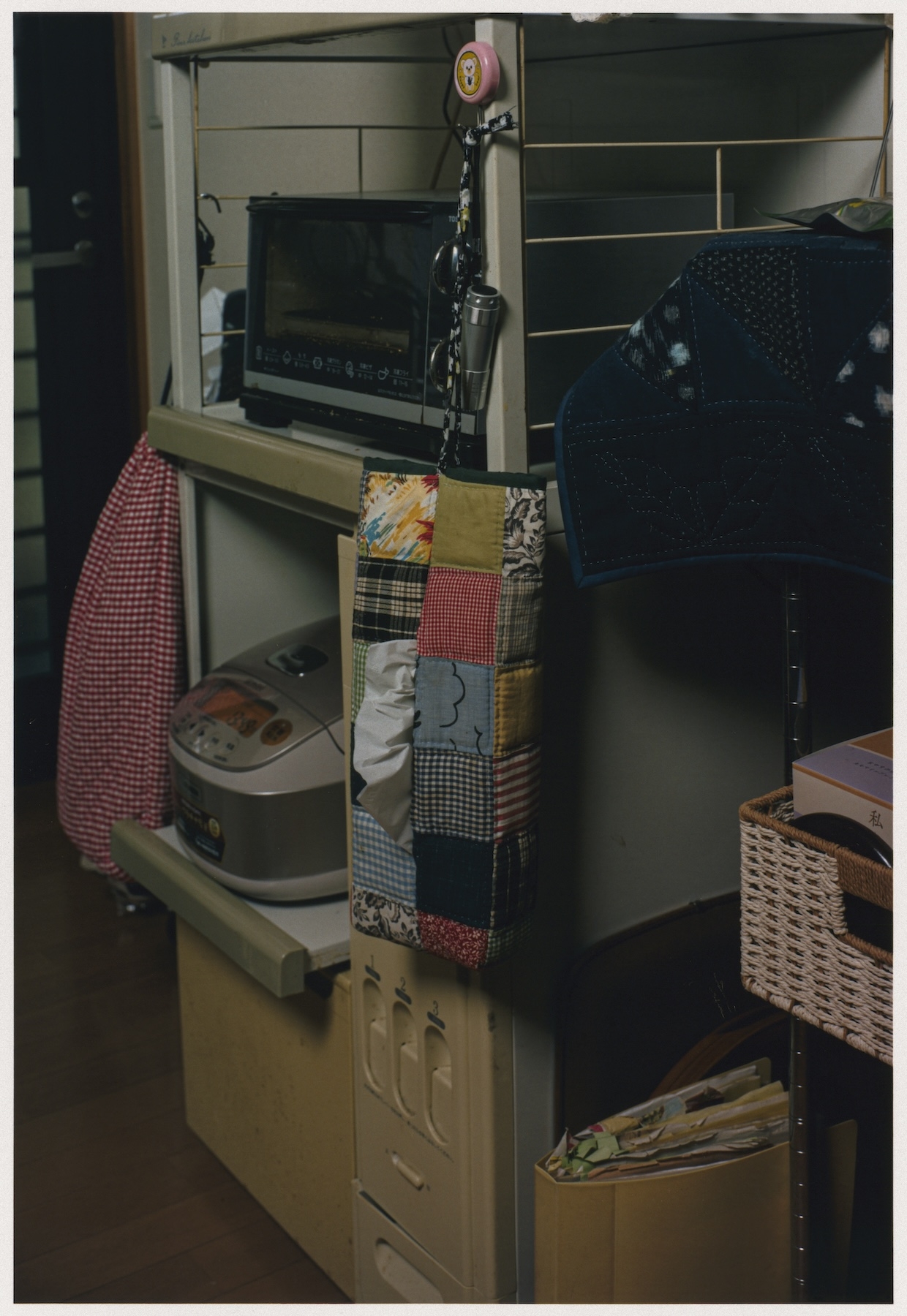

Tatsuki Masaru, Tissue Case, 2025, photographed August 2024, Toyamaより

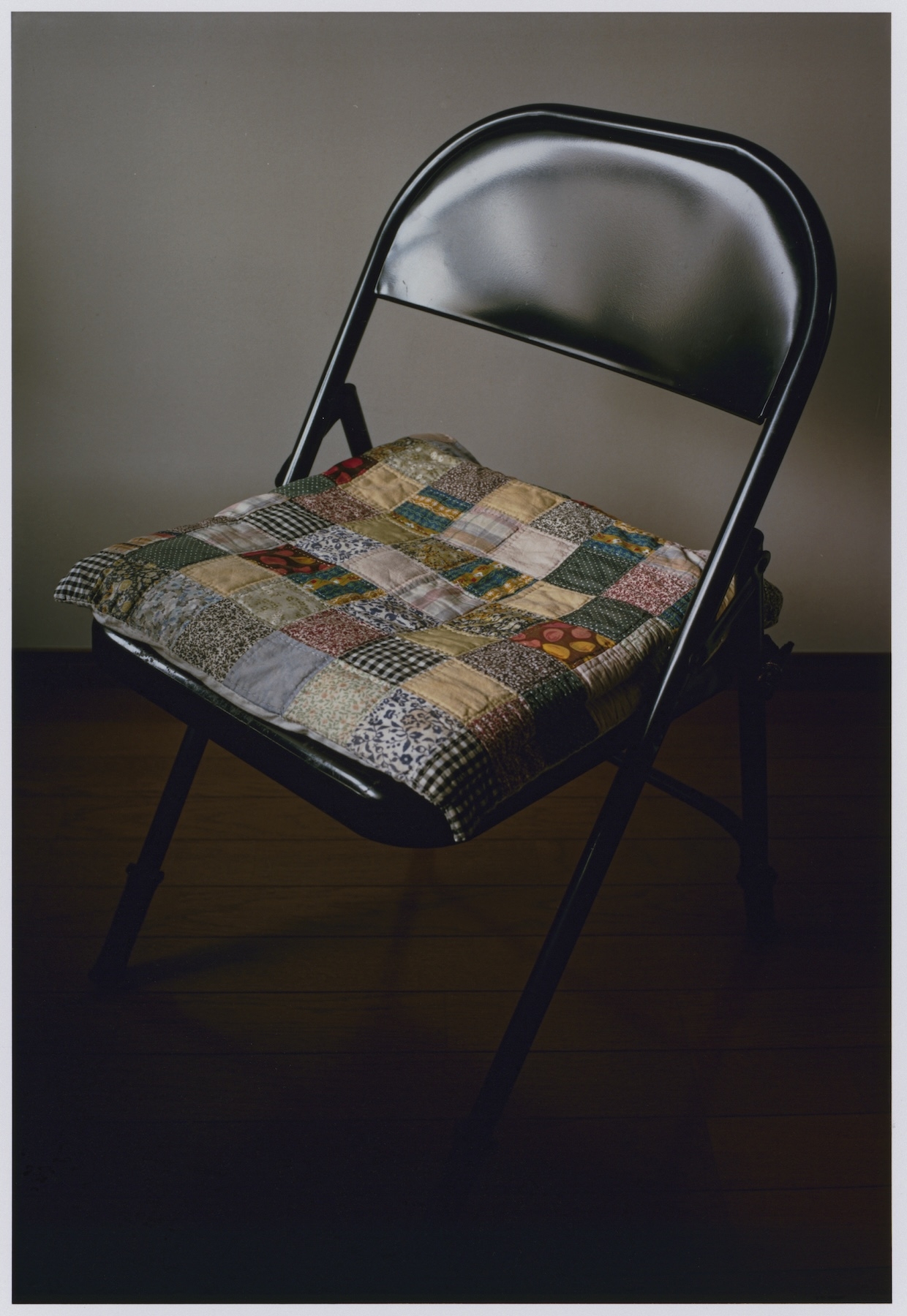

Tatsuki Masaru, My School Pouch, 2025, photographed February 2024, Saitama

From the second photo onward we find still life relics of the deceased. In order of appearance these are: the interior of a sewing box; a quilted bag tucked away in a corner; closeups of stitched quilting (multiple); a quilted tissue case; cute characters and soft toys, applique; quilted wall hangings (several), a smooth, shiny kettle and quilted trivet, a pot-holder (corner of the kitchen); a cover for an electric heater (?) (with Mickey Mouse motif; quilted, naturally); a quilted bag for “Reiko” (the sister, one presumes); a quilted drawstring bag (with Mickey Mouse applique ) for “Masaru” (the brother); a quilted bedcover; folding chair with square quilted cushion; scraps of fabric for quilting; the mother’s sewing table (dimly lit); a portrait of her; a living room sofa bereft of its owner; and a quilted wall hanging.

What does this set of photographs tell us? Firstly that the “Mama” in question was a dedicated quilter. Sewing was her hobby, and she probably mended old clothes, and made all the children’s apparel and other fabric items herself. Leftover scraps of fabric were quickly turned into quilting. But a look at the larger pieces, such as the wall hangings, reveals these to be of a level above and beyond the mere recycling of fabric oddments. It is obvious that the quilting in these instances was a more proactive endeavor, an artistic offering. The second mystery is “Mama’s” obsessive pursuit of this passion.

Photos like the closeups of quilting, the thimble from the sewing box, are images of seams and stitching, and reflect the time spent quilting, one stitch at a time, by the “Mama” wearing the thimble. Some seams are scrupulously neat, others not so even; each reflects the sewer’s state of mind at the time. The polished kettle, the spotless kitchen walls, the sheen on the conscientiously-wiped synthetic leather back of the folding chair, on which “Mama” likely sat, all point to a punctilious personality.

Tatsuki Masaru, Mother’s Work Chair, 2025, photographed July 2024, Toyama

Mickey Mouse appears four times in total: on the knee rug in the snap on the cover, on Masaru’s drawstring bag, the cover for the heater, and a quilted knee rug (the same one that is on the cover). Mickey is affixed to items that cover or envelop (for keeping warm, for protecting equipment from dust), acting as a guardian of sorts. And the knee rug on the cover, and drawstring bag, make a connection between “Masaru” and that guardian.

Tatsuki Masaru, Mother’s Work Table No Longer in Use, photographed July 2024, Toyama

Overall the photographs are dark/underexposed in tone. Hardly surprising, one might say, for a collection assembled in grief. Yet the shot of the mother’s worktable, which appears immediately prior to her portrait, is the only double-page spread in the book, and the fact that around half the setting for this prolific quilter’s creative endeavors is sunk in darkness, must surely mean something.2 It suggests a dark side to her quilting, and in turn that the passion, or persistence, with which she applied herself to it, was a product of this dark side. It is not difficult to imagine a connection to the “Papa” absent from the photographs. The darkness is an attribute of “Papa.” He was around until Masaru was six or so, then no longer.

Quilting is the art of taking disparate scraps of fabric and joining them together in accordance with a new order. Each piece (of sewing material, or upcycled fabric) has a history (in the vein of, “You used to love that, you wore it when we went to the zoo, didn’t you?) In other words, when those scraps were still actively in use, was when “Papa” was still around. And the quilted items were already being produced. The passion for quilting is a passion for taking the disparate, the disjointed, and re-joining it to make something new each time. Now all becomes clear: it is family that is at risk of being torn apart, by “Papa’s” “darkness,” family that was in constant danger of shattering. “Mama” was continually stitching it all back together. Quilting was her way of resisting. “Masaru” played the role of guardian.

Tatsuki Masaru, First Photo from Mars, 2018, Asahi Shimbun July 21, 1976, photographed March 15, 2016, Suginami, Tokyo, from the series “KAKERA”

Tatsuki Masaru has a series titled “KAKERA,” for which he visits museums in various locations and photographs shards/fragments (kakera) of Jomon pottery accompanied by the newspaper originally used to line the storage box. The resulting works superimpose the 10,000 years of the Jomon era; a temporal snapshot from the newspaper current when the fragments were placed in storage (early Showa era onward); the present, in the form of our eyes “now,” and a distant future in which our civilization is similarly reduced to kakera. One suspects that as he photographed his mother’s quilting, Tatsuki came to realize her craft was no different to the act of taking photos (turning into fragments) and composing (rejoining) those fragments into a book or exhibition.

Masaru Tazuki “Mama,” with ceramics by Yuriko Morioka was held December 13, 2025 through January 30, 2026 at Gallery Side 2, Tokyo.

1. That answer is as follows: “During third or fourth grade I became strongly aware of that man I refuse to call my father being violent toward my mother, shouting abuse, breaking things in the house. When my sister started school and my mother returned to the nursing career she had left on marrying, and was juggling job and housework, the violence and verbal abuse grew even worse, until finally he left and went to live elsewhere. My mother, sister and I were still living in the house for a while, and one night, he suddenly turned up, shouting as he opened the front door and tried to come in. My sister hurried to the door and desperately pulled the knob, straining to shut him out. I took kendo lessons back then, and as he persisted in trying to force his way in, slashed at him with my bamboo sword, furiously striking and stabbing. Witnessing him in pain, I felt a curious sense of achievement. And simultaneously, fright at the realization that I could feel such an emotion.” From the final page of the Mama photobook.

2. The description of half the setting being sunk in darkness refers not to the photographic data here, but the photograph in the book.

Shimizu Minoru

Art critic. Professor, Faculty of Global and Regional Studies, Doshisha University. Regularly contributes essays and critics for art/photography books, magazines and museum catalogues including those of Daido Moriyama, Gerhard Richter, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Wolfgang Tillmans and other Japanese and international artists.

Selected publications: “The Art of Equivalence” in Wolfgang Tillmans, truth study center (Taschen, 2005); “Shinjuku, Index” in Daido Moriyama (Editorial RM, 2007); “Fiction and Restoration of Eternity” in Hiroshi Sugimoto: Nature of Light (Izu Photo Museum/Nohara, 2009); “Daido Moriyama’s Farewell Photography” in Daido Moriyama (Tate Modern, 2012); “Guardian of the Void” in Palais no. 19 (Palais de Tokyo, Paris), 2014; “Post-Provoke et Post-Conpora: La photographie Japonaise depuis les années 1970” (Pompidou Metz, 2017).