GAT 031 Yoshitake Mika

My Evolving Role as a Curator: Part 2

As an international curator Yoshitake Mika has been involved in many projects in museums and galleries. What are the differences in the circumstances and objectives of working in museums or galleries? The following is an excerpt from an online talk given on December 11, 2021.

ISHII Jun’ichiro (ICA Kyoto)

My Evolving Role as a Curator: Part 1

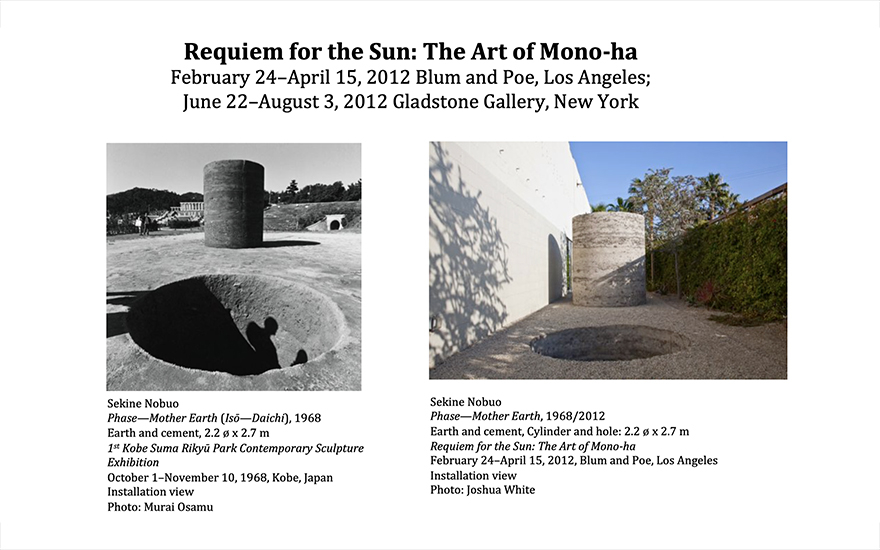

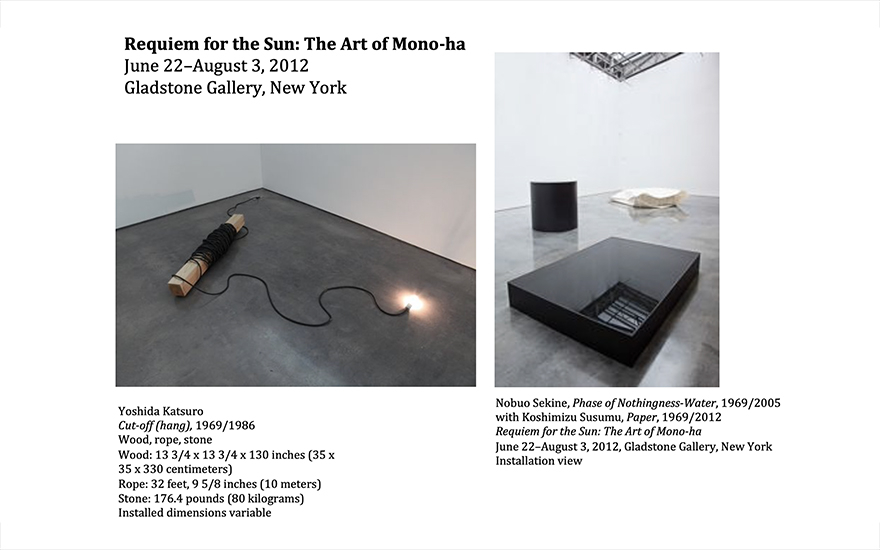

Next, I wanted to introduce my special projects at Blum & Poe, one “Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha”. This was a culmination of my dissertation on Mono-ha, where the objective of the exhibition was to revisit the artists ideas, as well as their works in a historically in a new context, but the space of the catalog was where I really explored the archival works as well as the theories and ideas of the artists where I also translated their writings, but the space of the exhibition was where I experimented with introducing the works themselves and they have their own language.

This is the Sekine Nobuo’s «Phase – Mother Earth», which is the legendary work that really introduced the movement and so, we had to site-specifically recreate this piece because it was no longer – it was a site-specific work, obviously.

I mentioned the objective for the exhibition was also a new understanding of the art subject within the terms of post-war Japanese art, as well as sculpture more broadly. The exhibition introduced specific terms and concepts introduced by the individual artists, as well as the methods where in which their works could be understood together.

My own role is as a second generation of – after a number of historic exhibitions that Mono-ha has presented since the early 80s, really, so, what was my contribution and I really thought very deeply about what could I do and so, as a student of contemporary art, foremost, I wanted to position the works through this comparative lens of post minimalism, land art, arte povera, but not applying those concepts onto them, but really focusing on the artists own ideas, and really trying to foreground that as part of the show.

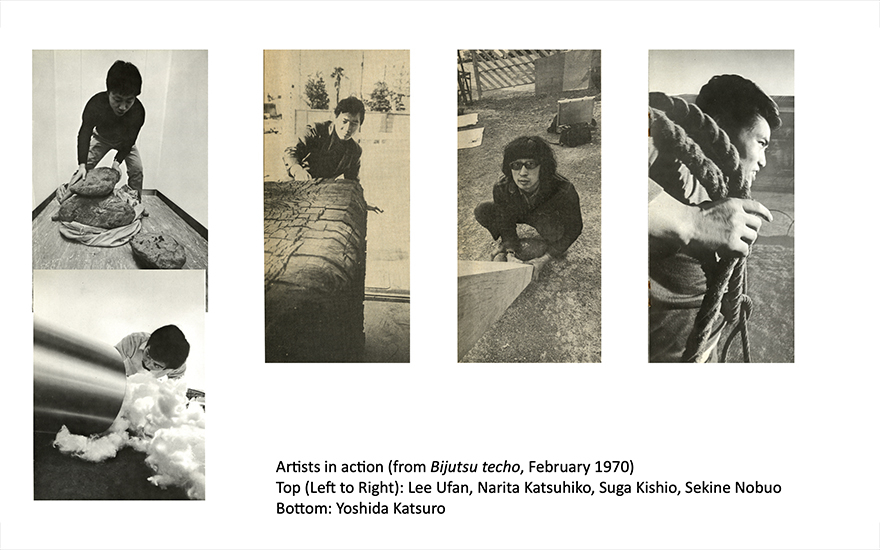

So for example, the Bijutsu Techo issue from 1970. This was actually, my mother had the whole collection of journals, but I saw these photos. This is when I first really learned about their work, but it was very process based, so I realized the works are act are live, there what I would call living structures, not static objects.

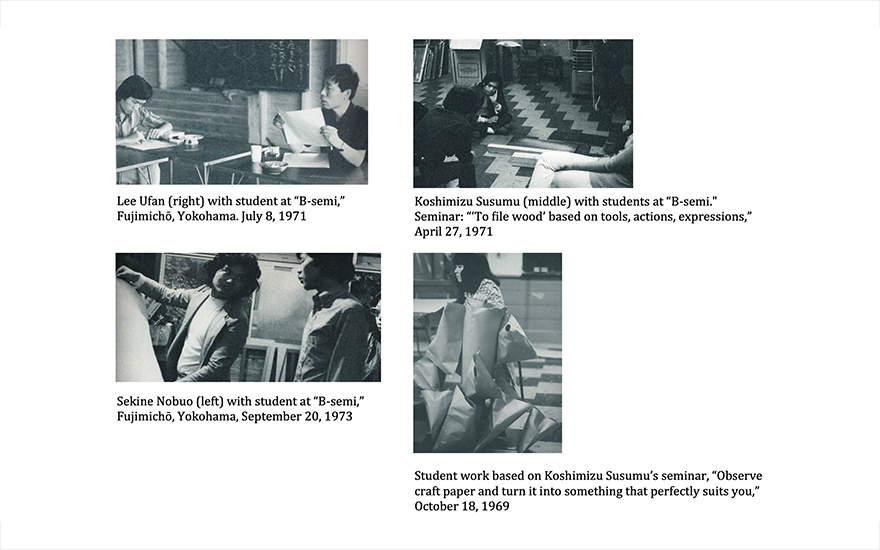

I also learned about their pedagogy at B-Semi, which was a different type of art school, each artist had their own teaching methodology, where they would have students experiment with different materials and spaces. So that was very eye opening for me.

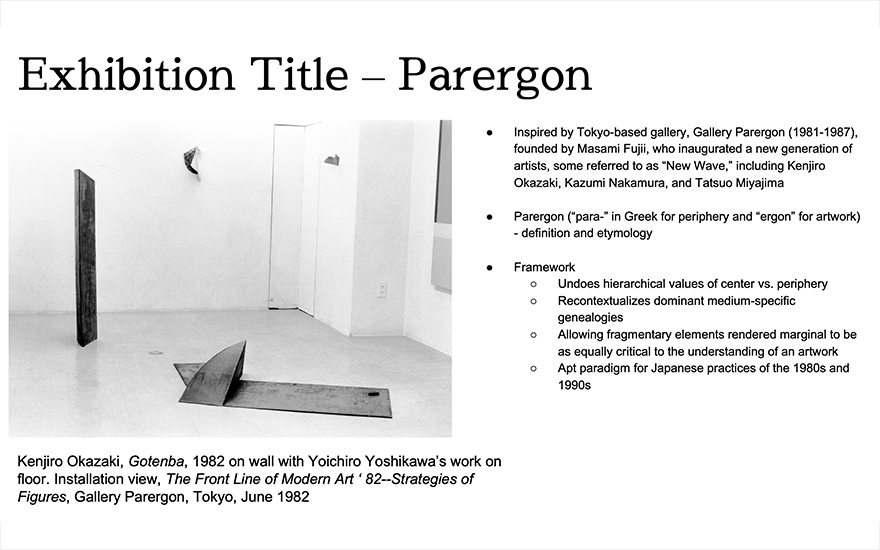

Next exhibition, the “Parergon” exhibition was the one that I had recently organized, inspired Tokyo-based gallery called Gallery Parergon (1981-1987), founded by Fujii Masami, who inaugurated a new generation of artists, some referred to as “New Wave”, including Okazaki Kenjiro, Nakamura Kazumi and Miyajima Tatsuo.

The term “Parergon” it is split between “para-” in Greek for periphery and “ergon” for artwork. It is basically a framework that undoes hierarchical values of center versus periphery, recontextualizes dominant medium-specific genealogies that allows for fragmentary elements rendered marginal to be as equally critical to the understanding of an artwork and it was a good paradigm for Japanese practices of the 1980s and 90s.

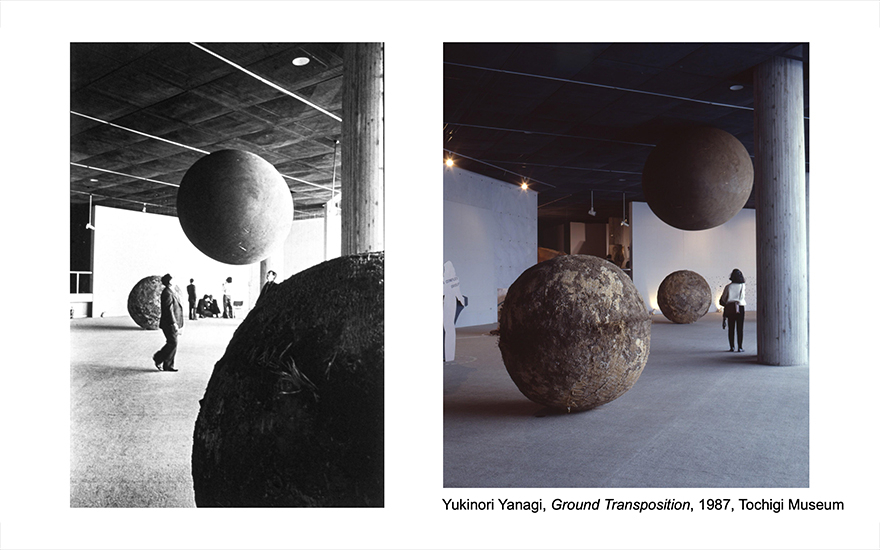

The show was also inspired by my own undergraduate thesis on Yanagi Yukinori and ground this installation called «Ground Transposition – 139°52’09” 36°33’52″» from 1987.

This work was influenced by Mono-ha and I learned about Mono-ha through Yanagi actually, this was connection. So, it was quite interesting to have this piece open the show.

It’s not just about Earth Art, but it pushes the institutional boundaries of what an artwork can be. The work is made of one helium balloon but surrounded by soil that is from in the original version, it was from Tochigi, but this helium balloon would go into other artist’s spaces. That was interesting for Yanagi to always kind of have this rebellious way of pushing the boundaries of – it was a Kinetic piece.

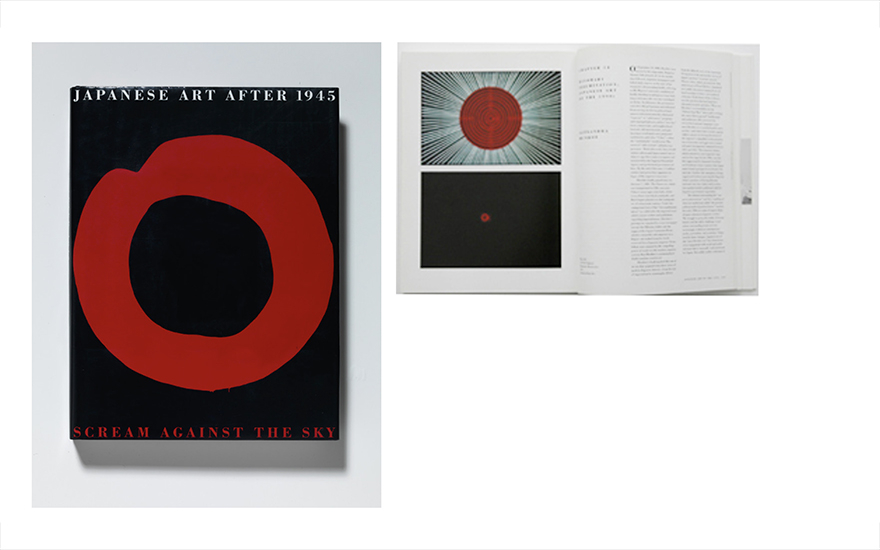

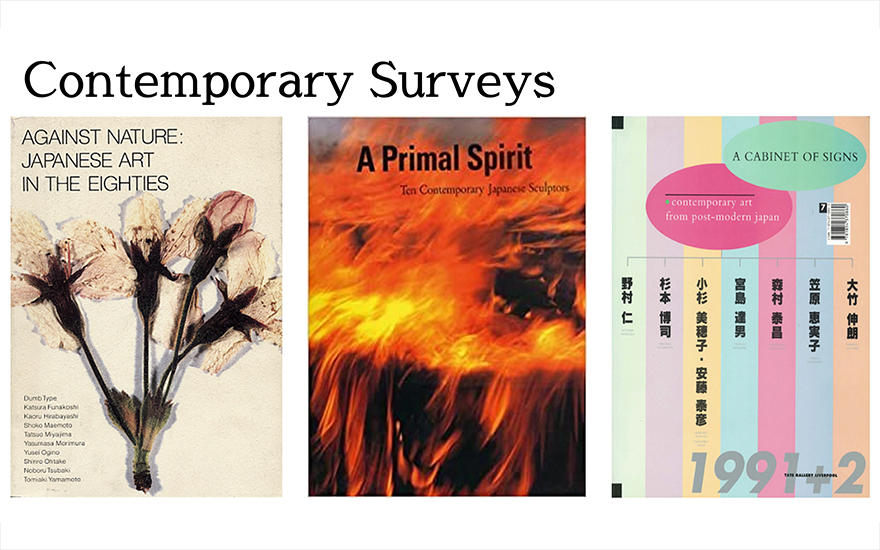

He was obviously introduced in Alexandria Monroe’s “Japanese Art after 1945: Scream Against the Sky” (1994-1995), and then I also was looking at various contemporary surveys of Japanese art in the US from 1989 around the time of the shift from Showa to Heisei, and very different kinds of shows, “Against Nature : Japanese Art in the Eighties” (1989), “A Primal Spirit: Ten Contemporary Japanese Sculptors” (1990) and “A cabinet of signs: Contemporary art from post-modern Japan” (1991).

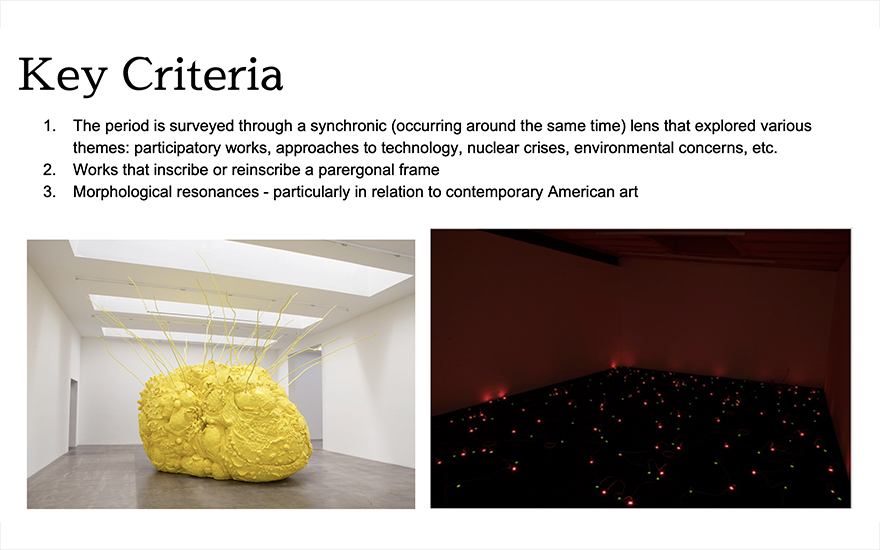

Some of the key criteria for the show was to survey the period through a synchronic, basically works that are occurring at the same time, there are a lot of works from 1989 that explored various themes, such as participatory works, approaches to technology, nuclear crises, environmental concerns. And then second, works that inscribe or reinscribe a parergonal frame. And then third, morphological or formal resonances, particularly in relation to contemporary American art.

What you see here is Tsubaki Noboru’s «Fresh Gasoline» as well as Miyajima Tatsuo’s «Sea of Time» both of which were introduced in 1989. We wanted to include in the exhibition of Blum & Poe, but also to reflect on it, I guess, 30 years later.

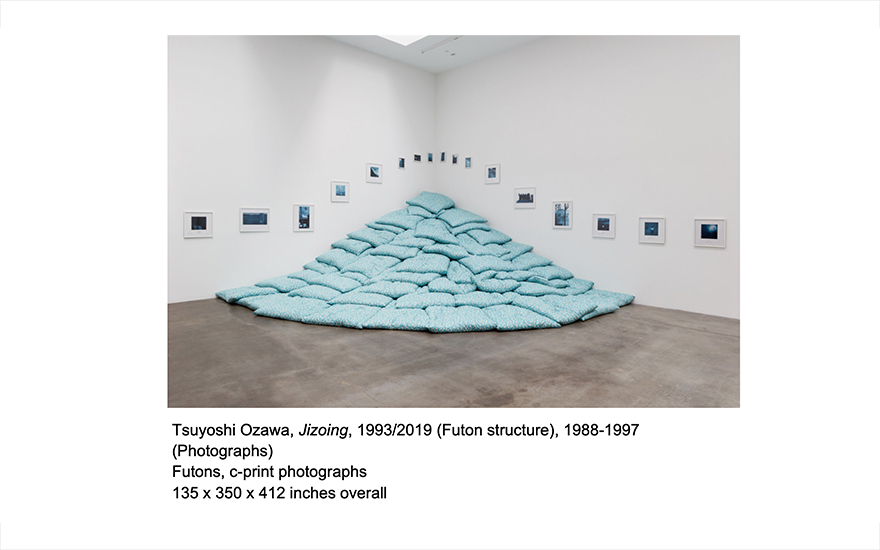

Participatory works Ozawa Tsuyoshi’s «Jizoing» which was probably one of the most popular works in the show, which you can climb up and then see the photographs, which are very politically charged sites. Sites of protest, sites of crises, various political movements.

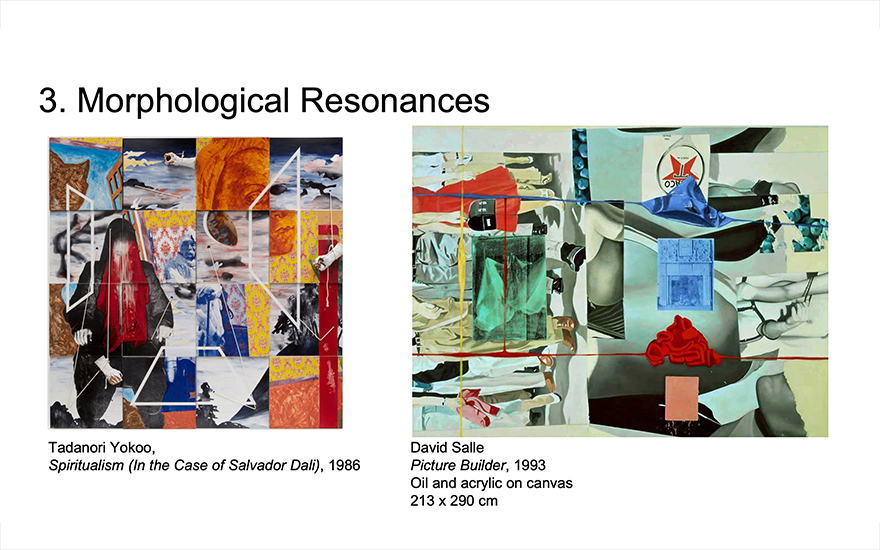

These are the morphological resonances. Yokoo Tadanori’s work was, we thought in relation to, for example, Neo expressionist painting from the U.S and I thought it was very resonant with some of David Salle’s paintings, especially these cut canvas works and I had a chance to really think about the differences, as well as similarities.

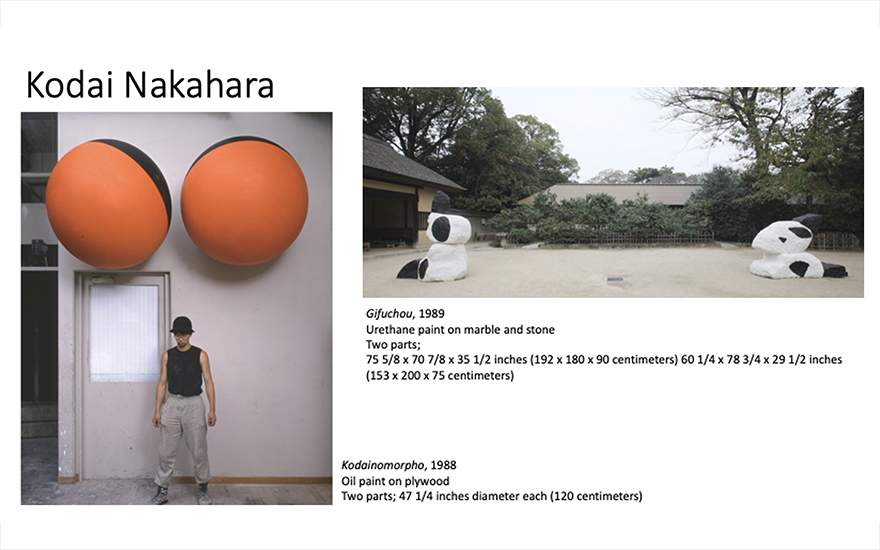

Nakahara Kodai’s work, which I was thinking in terms of new types of humorous, this almost surreal kind of sculpture, through other artist works like Irwin Wurm and Jim Hodges.

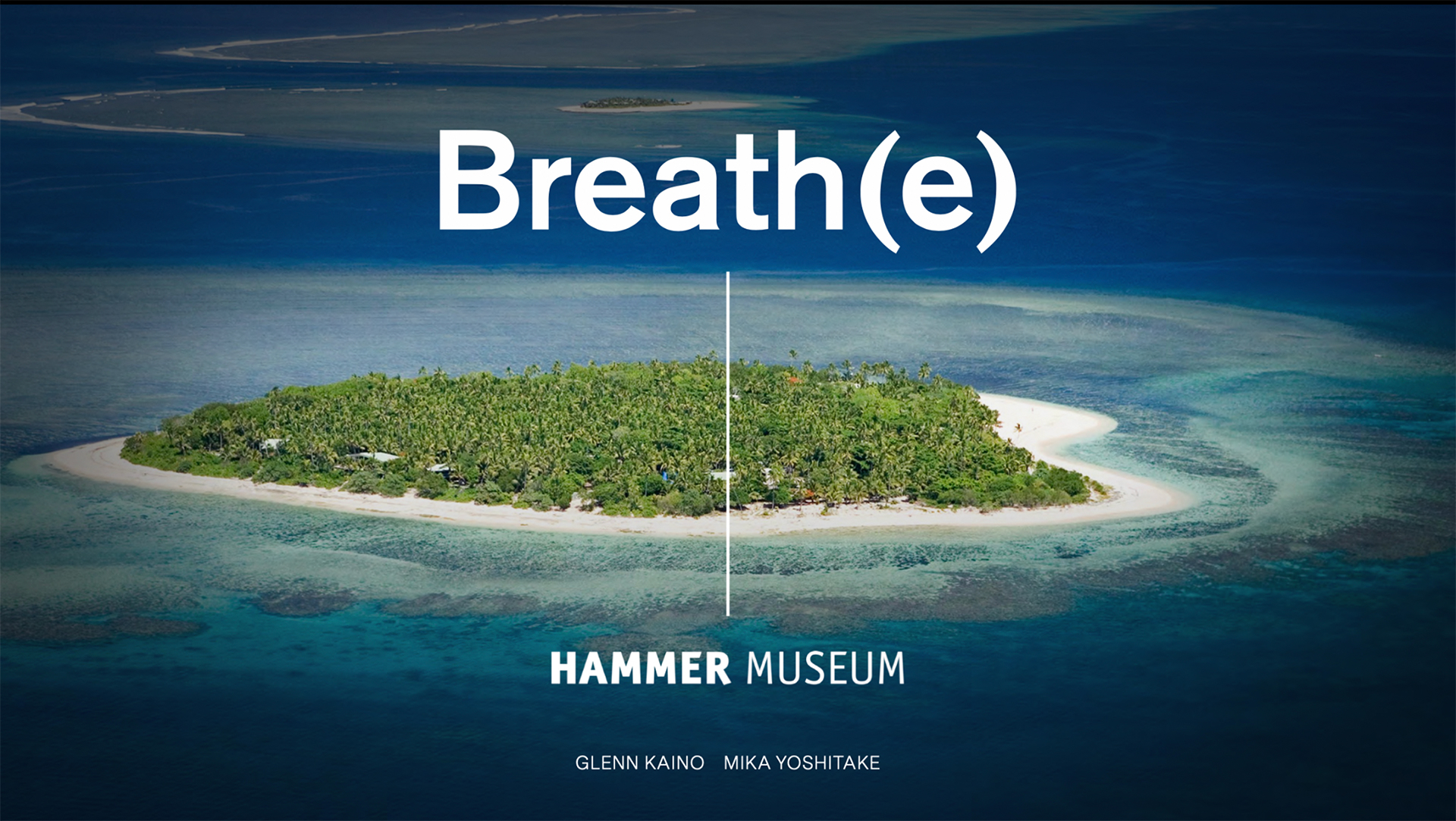

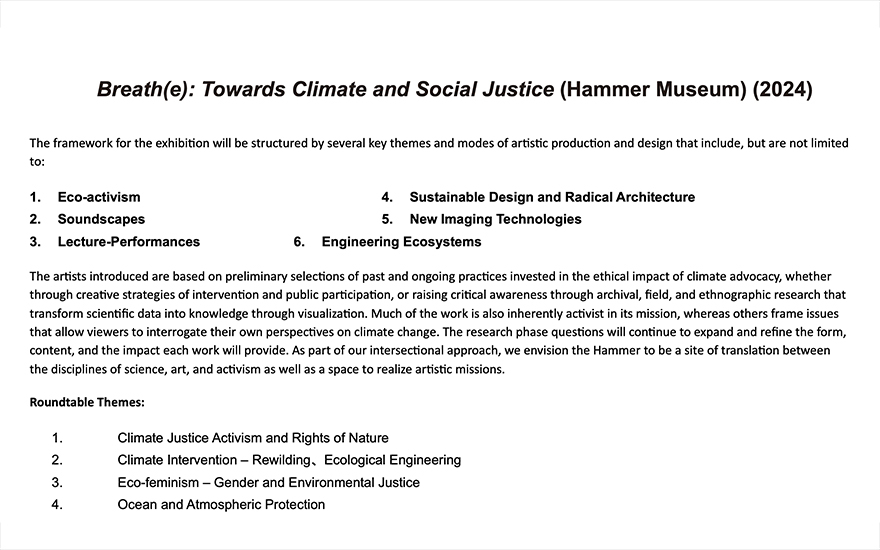

Finally, the upcoming show that I’m working on with Glenn Kaino, who’s an artist based in LA. The intention of this exhibition is an intersectional dialogue between climate justice and social justice, and we are working with carefully selected group of intergenerational and transdisciplinary contemporary artists, scientists, designers, architects, to create further knowledge about climate justice.

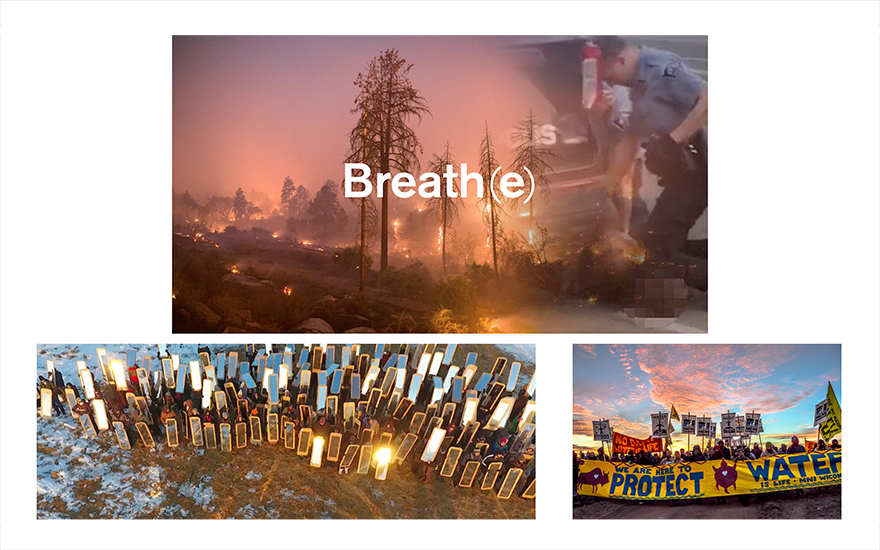

“Breath(e)” the exhibition title exists in a liminal state between objects and action, and it functions with, of course, the idea to assemble objects together for display but also to embrace praxis. A lot of the artists that we are we’re looking at really intervenes in and very Activist artwork.

We planned to look at unextractable links in-between racial violence and economic inequality, and the way the contemporary activists and artists have brought these issues to rights. A powerful example is protectors in Standing Rock against Dakota Access Pipeline, where accessed water was being threatened to indigenous communities. This is a piece called «Mirror Shield» by Cannupa Hanska Luger, who is from Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. These are DIY shield that are facing toward police, but also kind of activist installation or performances that really activate the community.

And of course, as an art historian, I have looked at some past exhibitions about the Earth art, eco aesthetics, sustainability. These are just some examples going into systems art, institutional critique and that really activate, it’s not just a representation of the artwork but or of climate change, but it’s really trying to instigate change in policy.

These are some of the key themes and modes of artistic production that we are considering. These are not final, but some that I can introduce are eco activism, soundscapes, lecture performances, sustainable design and architecture, new imaging technologies and engineering ecosystem.

Critically, how can we think inter relationally about the causes of climate change? This is important because, it’s not just all different kinds of categories, but how they all are affecting and impacting one another. The rising of ocean temperatures and ocean acidification, deforestation, overfishing, these are all they impact one another.

We’re looking at artists who can think inter relationally about these impacts. What are strategies that bring awareness to an intervene in the impacts of climate change. How can we assess solutions proposed by governments and institutions and individual actions against the power structures of political and economic interests and this is really critical, because we want to be self-reflexive about the museum’s role.

Especially since the Hammer Museum was founded by Occidental Petroleum, there’s inevitably questions surrounding that association, as well as the Getty Center is also founded by petroleum company. So, how can we utilize or think about the institution and the way that they are promoting the show, because there have been other examples, protests against museums that are sponsored by petroleum companies and stuff like that. So, you have to be very careful.

Then the visual cultures of climate change. There’s so many movies and documentary films that are so powerful, even mass media protests, so an investigative journalism, so how can Art really play a role in this vast cultural industry of visual climate change? What are the effective interdisciplinary artistic strategies? Integrating Art, Science, Engineering Design? And then finally, a much more philosophical question about how do we assume what constitutes the human and a shift towards the conceptual coexistence with nature.

How could we think about more ethically connected ways of using technology, highlight how technology can be used to interact with natural life more delicately, and also, to think about, the goal is really to ignite empathy and action for the protection of various ecosystems against climate change.

Mika Yoshitake

Mika Yoshitake is an independent curator with expertise in postwar Japanese art. She earned her MA and PhD in Art History from UCLA, which culminated in the AICA-USA award-winning exhibition Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha (2012). As former Curator at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (2011–18), she organized the six-venue North American tour of Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors (2017–19). Recent exhibitions include Parergon: Japanese Art of the 1980s and 1990s (2019) at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, Yoshitomo Nara (2021) at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and KUSAMA: Cosmic Nature (2021) at the New York Botanical Garden. She has forthcoming exhibitions at M+ Hong Kong and Breath(e): Toward Climate and Social Justice at the Hammer Museum as part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: LA x Art x Science in 2024.

* This talk was held online on December 11, 2021.