GAT 037 Rayyane Tabet

Space, Story, Situation

Rayyane Tabet, based in Beirut and San Francisco, creates sculptural works that explore his interest in the “history of materials,” “the process of making objects,” and “the transformation of narratives into physical forms.” Drawing from his personal experiences and extensive research, his work reexamines geopolitical events and social contexts, reconstructing them into tangible and visual expressions. With a background in architecture from his undergraduate studies, he incorporates his knowledge of materials and structures to develop new approaches to sculpture. How does he use personal narratives to interpret history and political phenomena? The following is an excerpt from a talk held on December 20, 2022.

Edited by Ishii Jun’ichiro (ICA Kyoto)

* Rayyane Tabet focused on his early work series, Five Distant Memories, when discussing the background of his artistic practice. For more details on this series, please refer to the previous article.

The reason why I usually take a lot of time describing or talking about this first series of works because for me they really became formative in my way of working and thinking, which is precisely this idea of the history of materials, the importance or the – my interest in object making, but also this obsession with how stories can be transformed into things or how stories can be kept into things. So I always consider these 10 years as – that it took me to make the series as also a lesson in how to balance the relationship between research, between object making and storytelling.

While working on this first series, I realized that in order for me to understand the world that I was born into, I had to figure out how this world came to be.

So I had to look at the geopolitical reality that made the conditions in which I was born. And that’s when I started the second series called the «Shortest Distance Between Two Points» that looks at the history of the world’s longest oil pipeline that connected Saudi Arabia to Lebanon.

It was this American multinational corporation that built and operated this pipeline as a way to get oil out of Saudi Arabia to European and North American markets, very quickly and cheaply, at a time right after World War II, where Europe and North America were concerned about their access to oil. This pipeline was operational between 1950 to 1983 and was responsible for the extreme wealth that was brought into Lebanon.

Lebanon became a very rich country because Saudi was exporting basically more than 50% of its oil from it. But the pipeline quickly could no longer – with the transformation of the region geopolitically, the pipeline became under attack. And so by 1983, following the wars in 1956, 1967, and 1973, it could no longer basically, carry this material.

The company collapsed and the pipeline stopped working. So today, this piece of abandoned infrastructure is the only physical object that crosses the borders of Saudi, Jordan, Syria, the Golan, and Lebanon, which are five political entities that are very conscious of their borders. And for me, it’s became a really interesting moment of thinking about infrastructure and geometry as vehicles for a reflection on politics and geography.

The main piece in this series is an attempt at actually remaking the pipeline in these sections. Every time I’m invited to show this particular series, I try to produce a section of it, usually in the country where I’m showing the project in. And so every section is the same diameter as the original pipeline, which is 80 centimeters. It’s the same thickness, which is 6 millimeters. And I produce it in 10 centimeter sections. And every section is engraved with how far you are from the point of origin, the longitude, the latitude and the elevation.

This piece that appears almost like a minimalist sculpture, when you get close to it, you’re drawn into the geography of these kind of places. But I was also interested in how –with the this pipeline no longer working, it actually turns from a piece of infrastructure to almost like a piece of land art. And this work then helps me think about its surrounding as much as it helps me think about itself.

When you see it in different contexts, it’s as much about the architecture or the conditions of where it’s shown than the piece itself. For example, here, we see it in relationship to the architecture of the Sharjah Art Museum or in relationship to the High Line in New York, which is a repurposed railroad that was turned into a park or in the interior of a music conservatory in Venice, or even as shown, back home in the desert of Al-Ula in Saudi Arabia.

I would say that a lot of the thinking behind the series is moments of foreshadowing, how can the past actually tell us about the future, and particularly in the history of this oil pipeline being a project that failed. In it is the beginning of understanding the failure of such projects in the future. And particularly today, when there is conversation again about resources and oil pipelines and who owns the oil, actually, this project really all of a sudden becomes very present, and that’s something that I’m really interested in.

In a way, if the «Shortest Distance Between Two Points» was me trying to understand the world that came right before my birth, then I was very curious to understand the world that came before the pipeline.

The next series that I’ll talk about is a series called «Fragments» that looks at an archaeological dig that happened at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of 20th century on a site in – that today sits on the border between Syria and Turkey, called Tell Halaf.

This site had been excavated by a German archaeologist called Max von Oppenheim who had also worked as a diplomat between basically, Egypt and Iraq and had to uncover this very unusual site that he became obsessed with. And in a way by virtue of accidents or history, my great grandfather had worked on this very site as Max von Oppenheim’s personal secretary for a period of 6 months.

In 2016 I was invited to do an artist residency in Berlin. I decided to basically follow the story and see where it would lead me. When I started doing research on Max von Oppenheim, I quickly learned that most of the objects that he brought back with him to Berlin were held at the Pergamon Museum. So I just contacted the conservators at the museum, asking if I could just meet them to show them some of the photographs that I had found in my family archive of my great grandfather working on the dig.

A week after arriving to Berlin, I met with them, which was supposed to be just a very quick, 1 hour casual meeting. And then when I showed them the photos that I had with me, they looked at me and they said, we’ve been waiting for you for all these years. Because in all the photos they had, which are the official photos of the dig, my great grandfather, which is a minor character in the story is always standing in the background, and he has no name. But in the photos that I had, he’s standing in the foreground and his name, because I know his name.

And that’s when this almost accidental encounter turned into this very complicated, story. And that’s when I heard these stories that basically in the 1930s when Max von Oppenheim returned to Berlin with all the objects that he had uncovered in Syria, he had tried to donate them to the Pergamon Museum, who refused them.

He opened his own private museum in Berlin. And during the Second World War, during the allied bombing of Berlin, that museum was actually targeted. And most of the objects that were held there were destroyed into 27,000 fragments that had then been gathered by Oppenheim and kept in storage in the Pergamon Museum until the reunification of Germany in 1990, when these two conservators that I had met, started piecing back together this puzzle made out of 27,000 pieces.

The exercise of bringing back together all these fragmented pieces took them 10 years. And at the end of those 10 years, they were left with 1,000 pieces that came from inside these sculptures that they could not put back together. And so they were left with these objects that, in a way, they couldn’t do much with them. They can’t show them in the museum, but they also can’t throw them away. And so I started a conversation with them about this idea of these unidentified objects.

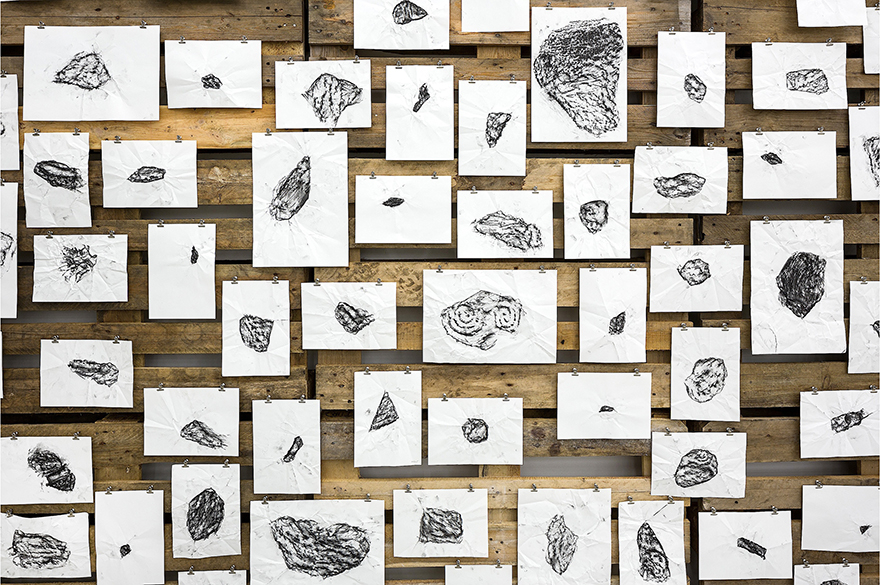

Basically, for me, the power of the story, lied not in the objects that they were able to put back together, but precisely in these 1,000 fragments that no longer could be put back together. I asked if I could access these 1,000 fragments and if I could make rubbings of every single one of them in a way to keep not only a record of them, but to give them – by way of these installations, give them importance or center stage. This material that’s supposed to be left over, that’s supposed to be the failure of this kind of exercise of bringing back together, becomes very similar to the figure of my great grandfather, the most important part of my project.

This led to a series of collaboration with these two conservators on other pieces that really thought a lot about this idea of fragmentation, preservation, particularly at a moment where, around 2016, there was a lot of conversation about the preservation of cultural heritage, particularly with the news that was coming in from Syria. And for me, it was an important reminder that the history of preservation should also take into account, destruction of cultural heritage that happened in the West, by allied forces, seemingly for freedom. In order for us to think critically about – again, our present moment, we had to expand these questions to include a past in which maybe we are also perpetrators of the crimes we accuse others of doing.

Maybe the last project in this series that I’ll talk about is this piece, that maybe brings back together those two elements that I was talking about, a personal aspect and a very almost scientific or objective way of looking at things. And it’s the story of a rug that was made out of goat hair that was given to my great grandfather by the Bedouins of Tell Halaf right before he finished his work there in 1929.

Before my great grandfather died in 1983, he had no money or property to give to his children. His will was that this rug be divided into five pieces so that each of his children would get one piece, with the provision that each child has to cut their piece among their children and so on and so forth until the rug will eventually disappear.

The rug today is divided across five generations in, I think 24 pieces. And so in it is that, almost again, beautiful, poetic, perverse, magical moment where, an original object, weirdly enough, in order for it to be preserved, has to be actually cut apart.

* Tabet went on to introduce his more recent works as well, but due to space constraints, not all of them can be included in this article. We hope to feature his latest projects in a future opportunity.

Rayyane Tabet

Rayyane Tabet is an artist who lives and works between Beirut and San Francisco. Drawing from experience and self-directed research, Tabet explores stories that offer an alternative understanding of major socio-political events through individual narratives. Informed by his training in architecture and sculpture, his work investigates paradoxes in the built environment and its history by way of installations that reconstitute the perception of physical and temporal distance. His most recent and upcoming solo shows include the Sharjah Art Foundation, Walker Art Center, Storefront for Art and Architecture, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art, The Louvre Museum, Carré d’Art in Nîmes, Kunstverein in Hamburg, and Kunstinstituut Melly (former Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art). His work was featured in the 7th Yokohama Triennial, Lahore Biennial 2, Manifesta 12, the 21st Biennale of Sydney, the 15th Istanbul Biennial, the 32nd São Paulo Biennial, the 6th Marrakech Biennale, the 10th & 12th Sharjah Biennial, and the 2nd New Museum Triennial.

* This talk was held at the Kyoto University of Arts on December 20, 2022.