Review

Inside a virtual cave – Voice of Void review

By Fukushima Ryota

2021.10.26

All the photos by Sawada Hana, Courtesy of Kyoto Experiment.

Ibuse Masuji’s well-known short story “Sanshouo” (Salamander) is the tale of a pitiful little creature whose head grows too large for him to leave the small cave he is in. Setting aside what Ibuse himself was trying to suggest allegorically here, it is certainly not hard to find parallels between the laughable figure of the salamander, and the intellectuals, in particular philosophers, of Japan’s modern era up to World War II.

Though not European themselves, thinkers during this period of Japanese history ploughed their way through the most impenetrable of European philosophy treatises, eventually arriving at some original ideas, such as the philosophy of Nishida Kitaro. It is hard not to be amazed by their dogged dedication. Yet when these same philosophers found themselves in the midst of a world war in the 1940s, their planet-sized brains conversely proved to be a liability. In particular, the inordinately abstract philosophy of the so-called “Kyoto School” formed the ideological counterpart to Japan’s wartime Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere, and as a result, underwent a purging of sorts in the post-war years. The flipside of the philosophers’ fall from favor was the rise of political scientists like Maruyama Masao to star status in academic circles.

Yet to claim the discourse of these men had any political validity would also be to overstate matters somewhat. The philosophy of the Kyoto School was truly in the “salamander” vein. Taking Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche et al as their starting point, they contrived to set out a “philosophy of world history” that dismantled Eurocentrism. But doing so had the effect of sealing them in a cave of swollen ideas, in turn sullying their reputations with the stain of wartime Imperial collaboration. That is to say, unable to support the weight of their ballooning brains, they ended up pratfalling. As a result, their grand, grandiose ideas now seem somehow comical, even ridiculous.

What Ho Tzu Nyen has tried to do in Voice of Void is to summon within a work of art the spirits of these philosophers driven into an odd ideological exile. Note that the thinkers appearing here, that is the “Big Four” of the Kyoto School – Kosaka Masaaki, Nishitani Keiji, Koyama Iwao and Suzuki Shigetaka – plus the likes of Miki Kiyoshi and Tosaka Jun, who are categorized as belonging to the Kyoto School left, are all of largely the same generation as Ibuse.*

What Ho Tzu Nyen has tried to do in Voice of Void is to summon within a work of art the spirits of these philosophers driven into an odd ideological exile. Note that the thinkers appearing here, that is the “Big Four” of the Kyoto School – Kosaka Masaaki, Nishitani Keiji, Koyama Iwao and Suzuki Shigetaka – plus the likes of Miki Kiyoshi and Tosaka Jun, who are categorized as belonging to the Kyoto School left, are all of largely the same generation as Ibuse.*

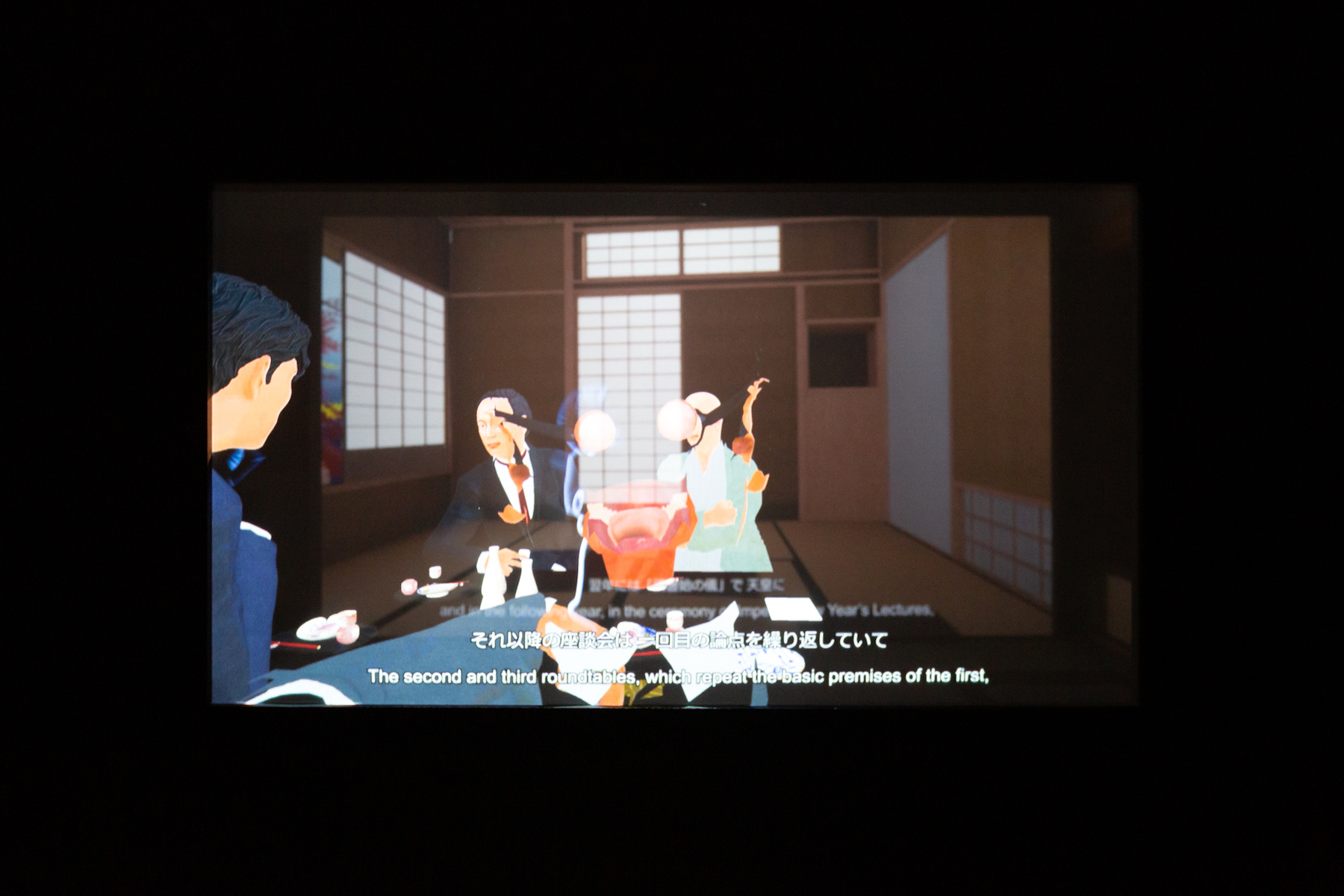

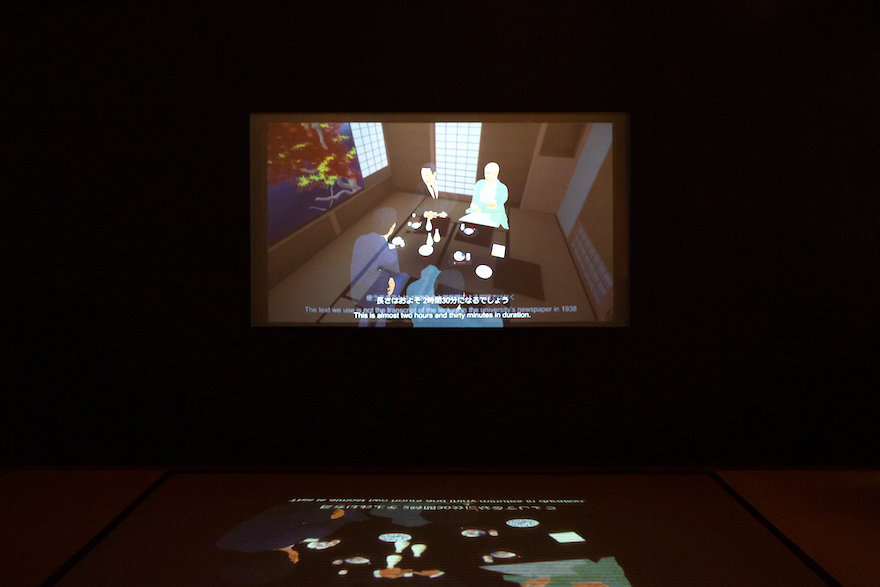

Centering his work on the Saami Tea Room, location of a round-table discussion titled “Sekaishi-teki tachiba to Nippon” (The standpoint of world history and Japan) involving Kosaka, Nishitani, Koyama and Suzuki, featured in the New Year 1942 issue of literary journal Chuo Koron, Ho has made the section above this “sky” and below it, “prison” and integrated the three layers using VR technology. While in the sky the mass-produced Zaku robots of Mobile Suit Gundam head off to battle, beneath the ground Miki and Tosaka – both of whom died of untreated scabies while detained under the Peace Preservation Laws – are shut in cramped jail cells. The tea room where the four philosophers sit is presented as a closed sphere, their voices echoing meaninglessly in this floating bubble.

Centering his work on the Saami Tea Room, location of a round-table discussion titled “Sekaishi-teki tachiba to Nippon” (The standpoint of world history and Japan) involving Kosaka, Nishitani, Koyama and Suzuki, featured in the New Year 1942 issue of literary journal Chuo Koron, Ho has made the section above this “sky” and below it, “prison” and integrated the three layers using VR technology. While in the sky the mass-produced Zaku robots of Mobile Suit Gundam head off to battle, beneath the ground Miki and Tosaka – both of whom died of untreated scabies while detained under the Peace Preservation Laws – are shut in cramped jail cells. The tea room where the four philosophers sit is presented as a closed sphere, their voices echoing meaninglessly in this floating bubble.

Making philosophy texts a setting for art was always going to require an unconventional approach, and to tackle the challenge, Ho chose VR technology. Confined within a virtual reality, the viewer experiences vicariously the philosophers in their literal sphere of ideas, the prisoners languishing in jail, and the robots heading off to battle (these three scenes are explained in more detail in videos in other rooms). This does not make for comfortable viewing: donning the weighty headset, subjected throughout to incursion by a voice whispering texts in the manner of an incantation, and rendered immobile like the salamander, in order to operate the VR the viewer must move their hand in the fashion of a stenographer transcribing the discussion. Seen from outside, that lack of freedom doubtless does look very comical.

Making philosophy texts a setting for art was always going to require an unconventional approach, and to tackle the challenge, Ho chose VR technology. Confined within a virtual reality, the viewer experiences vicariously the philosophers in their literal sphere of ideas, the prisoners languishing in jail, and the robots heading off to battle (these three scenes are explained in more detail in videos in other rooms). This does not make for comfortable viewing: donning the weighty headset, subjected throughout to incursion by a voice whispering texts in the manner of an incantation, and rendered immobile like the salamander, in order to operate the VR the viewer must move their hand in the fashion of a stenographer transcribing the discussion. Seen from outside, that lack of freedom doubtless does look very comical.

VR technology as it stands right now imposes a considerable physical burden on the viewer. Of course, this does in a sense tie in with the ideologically closed nature of the Kyoto School. Ho himself likely also has an obsession with masochistic self-closure. Perhaps recollections of philosophy and war are merely an excuse, and the true core of this work lies in guiding the viewer into a “virtual cave” governed by oppressiveness and suffocation.

VR technology as it stands right now imposes a considerable physical burden on the viewer. Of course, this does in a sense tie in with the ideologically closed nature of the Kyoto School. Ho himself likely also has an obsession with masochistic self-closure. Perhaps recollections of philosophy and war are merely an excuse, and the true core of this work lies in guiding the viewer into a “virtual cave” governed by oppressiveness and suffocation.

Personally, I was fascinated by the challenge Ho had set for himself, but feel duty-bound to also point out a number of problems with the work.

1. The video in the work is barely different to still images. Even the “sky” scene featuring the Zaku robots is seriously lacking in movement. Voice of Void patently comes off poorly compared to the technical sophistication of present-day anime. Even if more dynamic expression would not suit this particular work, the degree to which animation has already infiltrated our daily lives means that artists who use it need to have a rigorous strategy for their interventions. The video here did not seem like an animation to me.

2. The referencing of Gundam here struck me as rather unexpected. Gundam director Tomino Yoshiyuki was, after all, the filmmaker who endeavored to inherently move away from the previous generation of animations (such as Space Battleship Yamato) in which men marched in straight lines to overwhelm the enemy. In Gundam the drive for growth of friend and foe gathers pace, expanding, colliding, and triggering unforeseen chaos and disaster, in an ambitious recreation, within the framework of a robot cartoon, of the megalomania – whether Nazi Germany’s notion of a Thousand-Year Reich, for instance, or Japan’s concept of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere – that served as the signature tune of global war. Moreover, Tomino managed to do this while faithfully fulfilling his role as a businessman selling robot toys to children. Compared to Gundam, with this complex structure, or to the animated films of the likes of Miyazaki Hayao, Oshii Mamoru and Anno Hideaki, which have consistently dealt with war themes, the view of war in Voice of Void seems rather simplistic. Identification with Zakus is not enough to depict a war.

3. While in Voice of Void great care has been taken in the presentation, conversely, when it comes to the reinterpretation of Kyoto School texts, it has little new to offer. At least as far as I can see, the main thrust of the texts read out in this work is what is largely already known, with almost no surprises. If you’re going to make the effort to turn philosophy texts into a work of art, you do need, I think, to offer something extra.

Despite flaws like these that are hard to overlook, Ho’s revisiting of the Kyoto School does offer the viewer an access point for East Asian politics in the 21st century, because the “ghosts” of the Kyoto School still linger outside of Japan.

For example, Miki Kiyoshi’s cooperatism – a relationist philosophy preaching cooperation among the countries of Asia beyond the limits of liberalism, totalitarianism, and communism – has returned in today’s China as tianxiaism or the tianxia system (see the author’s book Hello, Eurasia). While critical of both self-righteous nationalism and individualistic liberalism, tianxianism lauds the concept of tianxia or “all under heaven” in which individuals are connected relationally, as the most universal type of system. Thought like this clearly corresponds ideologically to expansionist policies such as the Belt and Road Initiative, in the same way that the philosophy of the Kyoto School found its ideological equivalent in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch – born the same year as Tanabe Hajime, who is mentioned in Voice of Void – once said, “To think means to transgress” (The Principle of Hope [Das Prinzip Hoffnung]). Both the philosophers of the Kyoto School and China’s tianxiast ideologues unmistakably attempted to “transgress” something, that is, go out of bounds. However that “transgressive” thought process risks shutting them inside a cramped “virtual cave.” Voice of Void does accurately capture that paradox. It is thus ironic that the work itself has ended up similar to the salamander with the oversized cranium.

*Architect Kishida Hideto, film director Ozu Yasujiro, father of special effects Tsuburaya Eiji, critics like Kobayashi Hideo and Oya Soichi, and novelists such as Nakano Shigeharu and Kawabata Yasunari also belong to the same age cohort as Ibuse. They were the first generation of Japanese modernists to concern themselves with the power of technology to upset established humanism (needless to say they were also of the same generation as Emperor Hirohito, a biologist). The work of the Kyoto School and figures like Ibuse Masuji is not unrelated to this ideological context.

Fukushima Ryota

Literary critic. Associate Professor, Graduate School of Arts Field of Study: Comparative Civilizations, Rikkyo University. His latest book, Hello, Eurasia was published in 2021 by Kodansha.

※【KYOTO EXPERIMENT】Ho Tzu Nyen Voice of Void In collaboration with YCAM was held at Kyoto Art Center until October 24, 2021.

Though not European themselves, thinkers during this period of Japanese history ploughed their way through the most impenetrable of European philosophy treatises, eventually arriving at some original ideas, such as the philosophy of Nishida Kitaro. It is hard not to be amazed by their dogged dedication. Yet when these same philosophers found themselves in the midst of a world war in the 1940s, their planet-sized brains conversely proved to be a liability. In particular, the inordinately abstract philosophy of the so-called “Kyoto School” formed the ideological counterpart to Japan’s wartime Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere, and as a result, underwent a purging of sorts in the post-war years. The flipside of the philosophers’ fall from favor was the rise of political scientists like Maruyama Masao to star status in academic circles.

Yet to claim the discourse of these men had any political validity would also be to overstate matters somewhat. The philosophy of the Kyoto School was truly in the “salamander” vein. Taking Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche et al as their starting point, they contrived to set out a “philosophy of world history” that dismantled Eurocentrism. But doing so had the effect of sealing them in a cave of swollen ideas, in turn sullying their reputations with the stain of wartime Imperial collaboration. That is to say, unable to support the weight of their ballooning brains, they ended up pratfalling. As a result, their grand, grandiose ideas now seem somehow comical, even ridiculous.

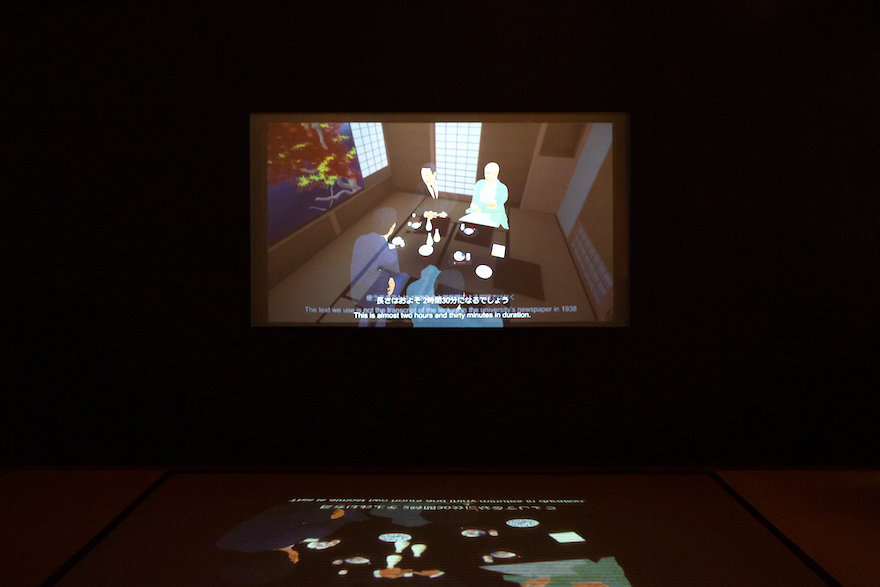

Installation view at Kyoto Art Center.

All the photos by Sawada Hana, Courtesy of Kyoto Experiment.

Personally, I was fascinated by the challenge Ho had set for himself, but feel duty-bound to also point out a number of problems with the work.

1. The video in the work is barely different to still images. Even the “sky” scene featuring the Zaku robots is seriously lacking in movement. Voice of Void patently comes off poorly compared to the technical sophistication of present-day anime. Even if more dynamic expression would not suit this particular work, the degree to which animation has already infiltrated our daily lives means that artists who use it need to have a rigorous strategy for their interventions. The video here did not seem like an animation to me.

2. The referencing of Gundam here struck me as rather unexpected. Gundam director Tomino Yoshiyuki was, after all, the filmmaker who endeavored to inherently move away from the previous generation of animations (such as Space Battleship Yamato) in which men marched in straight lines to overwhelm the enemy. In Gundam the drive for growth of friend and foe gathers pace, expanding, colliding, and triggering unforeseen chaos and disaster, in an ambitious recreation, within the framework of a robot cartoon, of the megalomania – whether Nazi Germany’s notion of a Thousand-Year Reich, for instance, or Japan’s concept of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere – that served as the signature tune of global war. Moreover, Tomino managed to do this while faithfully fulfilling his role as a businessman selling robot toys to children. Compared to Gundam, with this complex structure, or to the animated films of the likes of Miyazaki Hayao, Oshii Mamoru and Anno Hideaki, which have consistently dealt with war themes, the view of war in Voice of Void seems rather simplistic. Identification with Zakus is not enough to depict a war.

3. While in Voice of Void great care has been taken in the presentation, conversely, when it comes to the reinterpretation of Kyoto School texts, it has little new to offer. At least as far as I can see, the main thrust of the texts read out in this work is what is largely already known, with almost no surprises. If you’re going to make the effort to turn philosophy texts into a work of art, you do need, I think, to offer something extra.

Despite flaws like these that are hard to overlook, Ho’s revisiting of the Kyoto School does offer the viewer an access point for East Asian politics in the 21st century, because the “ghosts” of the Kyoto School still linger outside of Japan.

For example, Miki Kiyoshi’s cooperatism – a relationist philosophy preaching cooperation among the countries of Asia beyond the limits of liberalism, totalitarianism, and communism – has returned in today’s China as tianxiaism or the tianxia system (see the author’s book Hello, Eurasia). While critical of both self-righteous nationalism and individualistic liberalism, tianxianism lauds the concept of tianxia or “all under heaven” in which individuals are connected relationally, as the most universal type of system. Thought like this clearly corresponds ideologically to expansionist policies such as the Belt and Road Initiative, in the same way that the philosophy of the Kyoto School found its ideological equivalent in the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch – born the same year as Tanabe Hajime, who is mentioned in Voice of Void – once said, “To think means to transgress” (The Principle of Hope [Das Prinzip Hoffnung]). Both the philosophers of the Kyoto School and China’s tianxiast ideologues unmistakably attempted to “transgress” something, that is, go out of bounds. However that “transgressive” thought process risks shutting them inside a cramped “virtual cave.” Voice of Void does accurately capture that paradox. It is thus ironic that the work itself has ended up similar to the salamander with the oversized cranium.

*Architect Kishida Hideto, film director Ozu Yasujiro, father of special effects Tsuburaya Eiji, critics like Kobayashi Hideo and Oya Soichi, and novelists such as Nakano Shigeharu and Kawabata Yasunari also belong to the same age cohort as Ibuse. They were the first generation of Japanese modernists to concern themselves with the power of technology to upset established humanism (needless to say they were also of the same generation as Emperor Hirohito, a biologist). The work of the Kyoto School and figures like Ibuse Masuji is not unrelated to this ideological context.

Fukushima Ryota

Literary critic. Associate Professor, Graduate School of Arts Field of Study: Comparative Civilizations, Rikkyo University. His latest book, Hello, Eurasia was published in 2021 by Kodansha.

※【KYOTO EXPERIMENT】Ho Tzu Nyen Voice of Void In collaboration with YCAM was held at Kyoto Art Center until October 24, 2021.