Review

“Unlimited World/Murakami Saburo” Review

By Shimabuku

2022.01.29

To be perfectly honest, I pretty much knew Murakami Saburo solely as the “kami-yaburi (paper-breaking) guy,” and the reason I absolutely had to go see this exhibition was that Kosugi Takehisa, who passed away in 2018, had been such an admirer of Murakami. I’ll never forget him expounding excitedly on “Sab’s brilliance!” Plus the venue, the Ashiya City Museum of Art and History, was where Kosugi-san staged the final exhibition of his life. That show had also been the last time we’d met, so it was with thoughts of him in my mind, that I headed to the museum. The exhibition there turned out to offer a valuable overview of Murakami’s career and works.

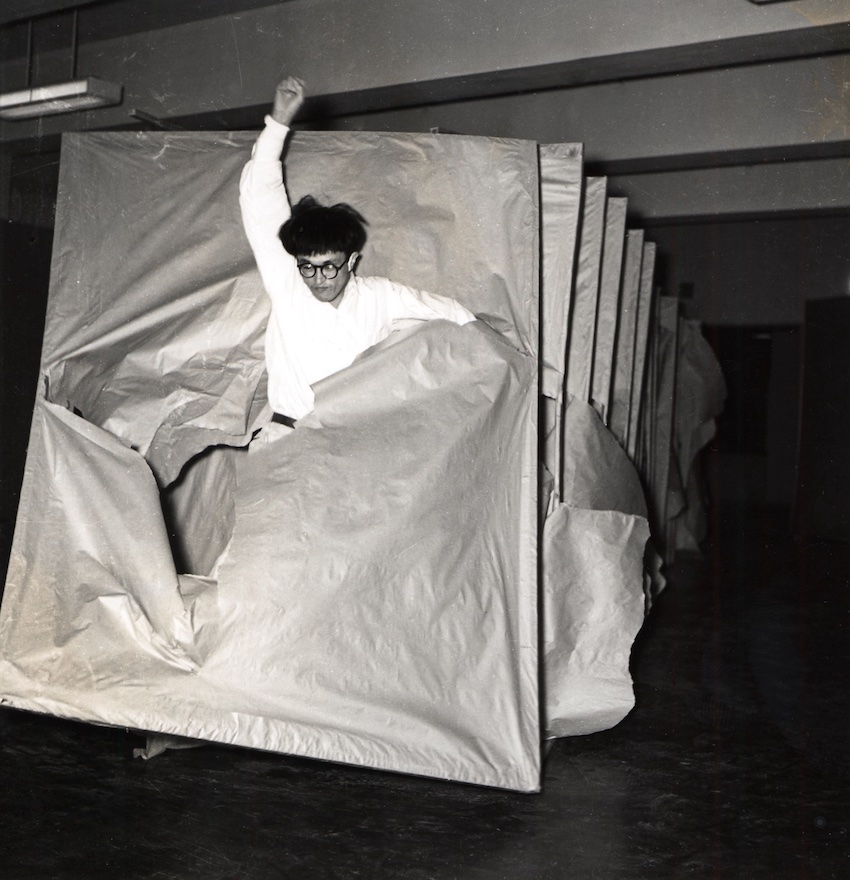

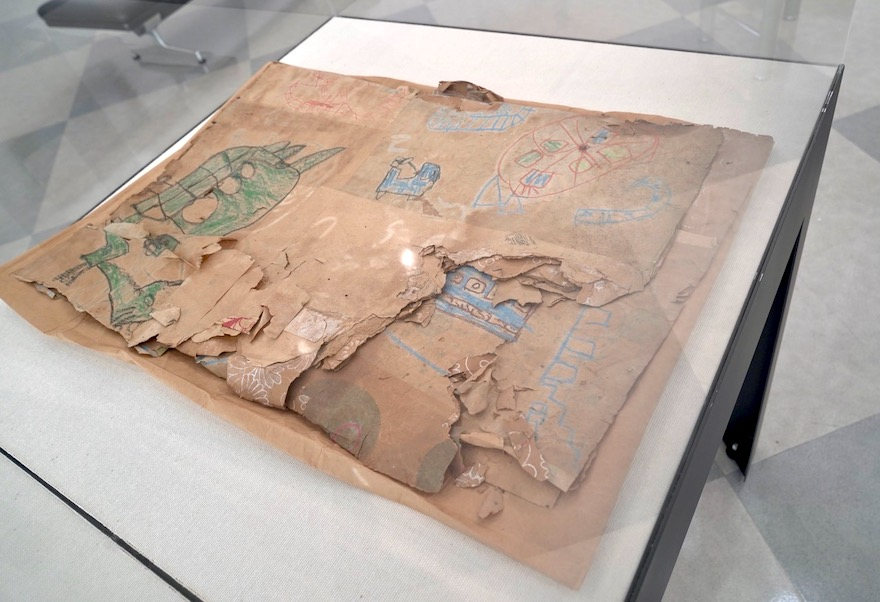

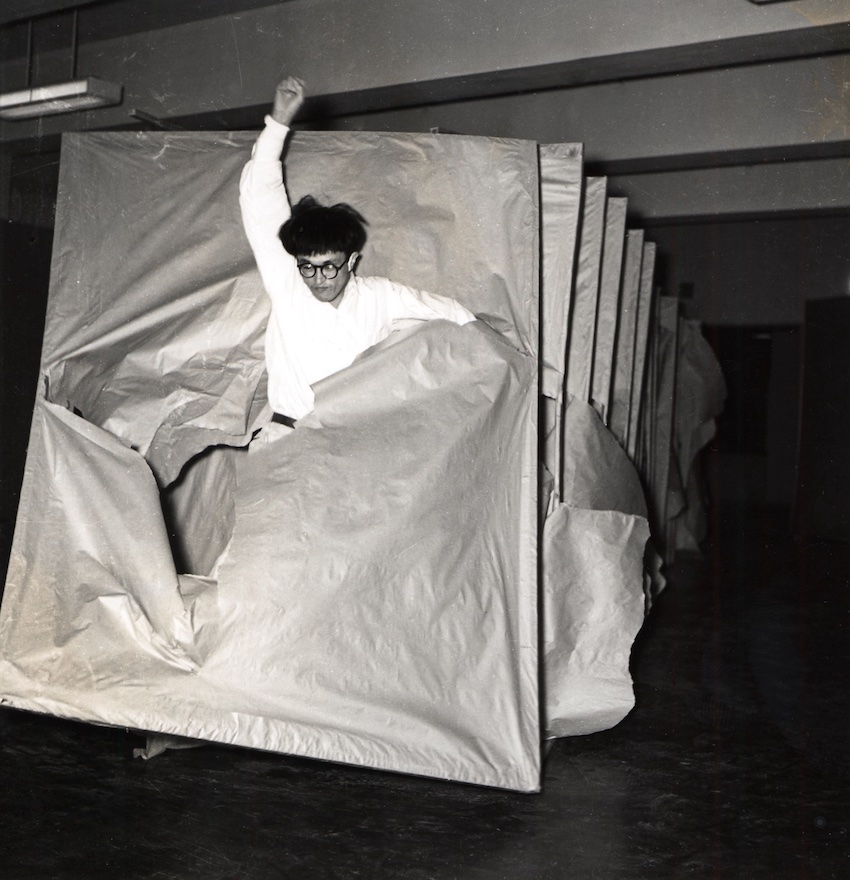

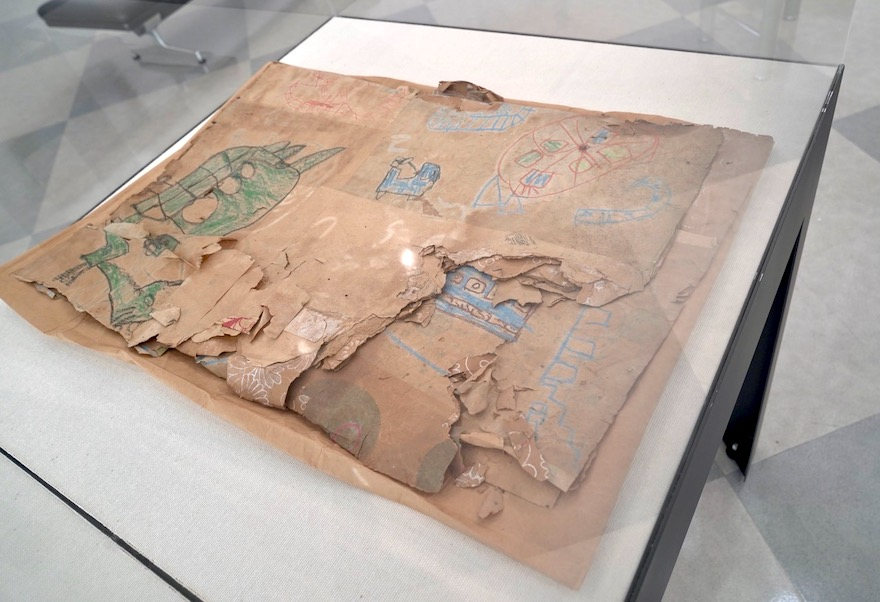

The beginning, on the ground floor with its atrium space, consisted entirely of “kami-yaburi” works. This was mainly in the form of displays of archival material, but what surprised me was the number of times Murakami actually staged his paper-ripping productions: almost forty, if you include associated projects, and in a slightly different iteration every time, say, for example, from a single sheet of paper to a succession. Size, color and conditions varied too. I also learned that each one had its own title, and “kami-yaburi” was just a general term for them all. The first, presented at the First Gutai Art Exhibition in 1955, was not in the form of a performance, but a picture Murakami had made at home, indicating that his kami-yaburi was inspired by painting. Apparently that first work was prompted by his three-year-old son bursting into the room through the fusuma (paper door), and the torn paper covered in crayon scribbles was displayed here like a venerated treasure. Other scraps of paper from kami-yaburi performances were also displayed, and I found myself feeling a strong affinity with the artist’s desire to hang on to anything and everything.

The beginning, on the ground floor with its atrium space, consisted entirely of “kami-yaburi” works. This was mainly in the form of displays of archival material, but what surprised me was the number of times Murakami actually staged his paper-ripping productions: almost forty, if you include associated projects, and in a slightly different iteration every time, say, for example, from a single sheet of paper to a succession. Size, color and conditions varied too. I also learned that each one had its own title, and “kami-yaburi” was just a general term for them all. The first, presented at the First Gutai Art Exhibition in 1955, was not in the form of a performance, but a picture Murakami had made at home, indicating that his kami-yaburi was inspired by painting. Apparently that first work was prompted by his three-year-old son bursting into the room through the fusuma (paper door), and the torn paper covered in crayon scribbles was displayed here like a venerated treasure. Other scraps of paper from kami-yaburi performances were also displayed, and I found myself feeling a strong affinity with the artist’s desire to hang on to anything and everything.

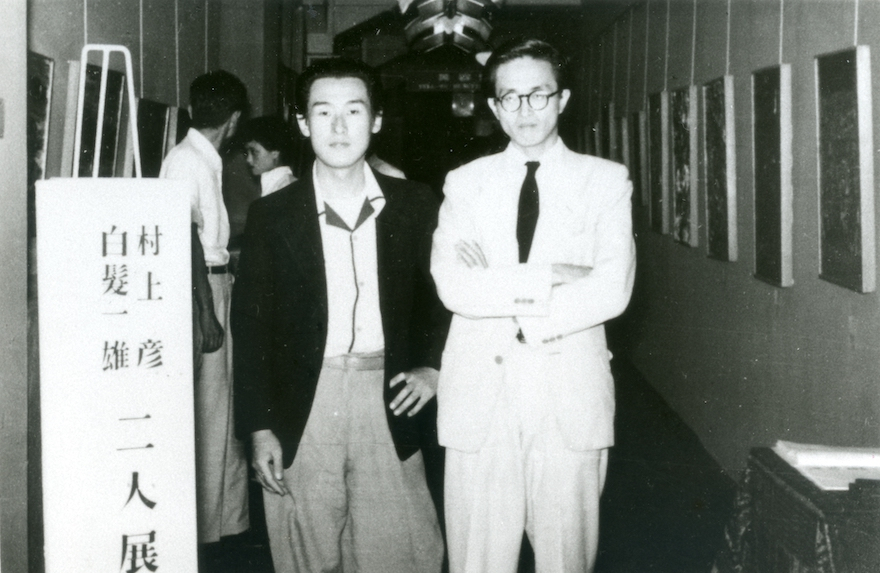

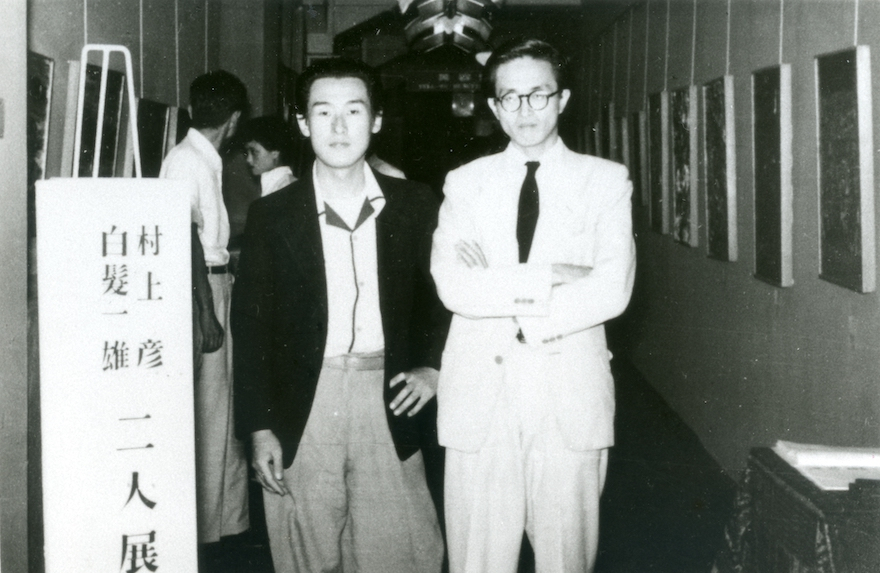

The display included a fascinating video compilation of several of Murakami’s kami-yaburi performances. Most of the footage was old and not very clear, but you could see the artist taking time to gather himself in front of the paper each time just before he burst through it. While ripping the paper he would abruptly flail his arms about, pushing his whole body ahead with some force. It struck me as similar in a way to the slashing of Japanese iai swordsmanship. I was reminded of Shiraga Kazuo, another Gutai artist, swinging from a rope fastened to the ceiling, thrashing about painting pictures with his feet. I learned later in the exhibition that Murakami and Shiraga were lifelong friends, and it didn’t surprise me that Murakami had exhibited alongside Shiraga early in his career, pre-Gutai. Their efforts were characterized by a calm, and a ferocious energy, akin to those seen in Japan’s ancient martial arts, partly due to the era, I suppose, and by a sense that this would never descend into parody. I contemplated the notion of the two of them, developing works together, aware of each other.

The display included a fascinating video compilation of several of Murakami’s kami-yaburi performances. Most of the footage was old and not very clear, but you could see the artist taking time to gather himself in front of the paper each time just before he burst through it. While ripping the paper he would abruptly flail his arms about, pushing his whole body ahead with some force. It struck me as similar in a way to the slashing of Japanese iai swordsmanship. I was reminded of Shiraga Kazuo, another Gutai artist, swinging from a rope fastened to the ceiling, thrashing about painting pictures with his feet. I learned later in the exhibition that Murakami and Shiraga were lifelong friends, and it didn’t surprise me that Murakami had exhibited alongside Shiraga early in his career, pre-Gutai. Their efforts were characterized by a calm, and a ferocious energy, akin to those seen in Japan’s ancient martial arts, partly due to the era, I suppose, and by a sense that this would never descend into parody. I contemplated the notion of the two of them, developing works together, aware of each other.

The last kami-yaburi, performed in 1994 at the Kawanishi City Shimin Hall, was the only one a little different. Here Murakami, dressed formally in black and wearing a hat, can be seen strolling in leisurely fashion from inside the building up to a sheet of white paper extended across what appears to be the hall door, and quietly breaking through it. A year or so after this, Murakami collapsed in front of his home, dying a few days later. It is almost as if he was predicting his own demise. What’s more, this kami-yaburi is titled Exit. Incidentally the most common title in the kami-yaburi series is Entrance. Murakami’s clothing and relaxed demeanor at this final kami-yaburi were reminiscent of American artist James Lee Byars, who was living in Kyoto around 1960. It struck me that with both artists residing in Kansai, they potentially could have met, and it would be interesting to look into this some more.

The last kami-yaburi, performed in 1994 at the Kawanishi City Shimin Hall, was the only one a little different. Here Murakami, dressed formally in black and wearing a hat, can be seen strolling in leisurely fashion from inside the building up to a sheet of white paper extended across what appears to be the hall door, and quietly breaking through it. A year or so after this, Murakami collapsed in front of his home, dying a few days later. It is almost as if he was predicting his own demise. What’s more, this kami-yaburi is titled Exit. Incidentally the most common title in the kami-yaburi series is Entrance. Murakami’s clothing and relaxed demeanor at this final kami-yaburi were reminiscent of American artist James Lee Byars, who was living in Kyoto around 1960. It struck me that with both artists residing in Kansai, they potentially could have met, and it would be interesting to look into this some more.

Heading upstairs I found a display of Murakami’s early figurative paintings, then in a room further in on the left were larger works from after his practice took an abstract turn, with glimpses here and there of Shiraga’s work, that is to say, of feet. It felt like seeing right into Murakami’s mind as he pondered how to confront Shiraga, who had invented such painting with the feet. Within that, Murakami himself had also been inventive, creating what again goes by a general term, that of “hakuraku suru kaiga” or “flaking-off painting,” and featured on the poster and flyer for this exhibition. These were originally about a size 500 canvas, of which apparently only sections remain today, and at first glance are fairly typical-looking abstract paintings in red and black. On closer inspection I found the black on the surface to be peeling and almost falling off; it seems paint does still flake off these pictures, the fallen fragments visible in the framed example. Here was a painting even now in progress, the aim right from the start being for the black to come off and expose the red paint below, and the white base. This sense of progressing, never stopping, is the true essence of Murakami Saburo, and applies just as readily to his kami-yaburi work. Murakami also takes the deterioration of works that is taboo in art and overturns it in splendid fashion akin to a decisive strike in a traditional Japanese martial art. I suspect this is also what Kosugi-san liked about Murakami’s work. I too am a big fan of this sensation of sword splitting bamboo with one precise cut.

Heading upstairs I found a display of Murakami’s early figurative paintings, then in a room further in on the left were larger works from after his practice took an abstract turn, with glimpses here and there of Shiraga’s work, that is to say, of feet. It felt like seeing right into Murakami’s mind as he pondered how to confront Shiraga, who had invented such painting with the feet. Within that, Murakami himself had also been inventive, creating what again goes by a general term, that of “hakuraku suru kaiga” or “flaking-off painting,” and featured on the poster and flyer for this exhibition. These were originally about a size 500 canvas, of which apparently only sections remain today, and at first glance are fairly typical-looking abstract paintings in red and black. On closer inspection I found the black on the surface to be peeling and almost falling off; it seems paint does still flake off these pictures, the fallen fragments visible in the framed example. Here was a painting even now in progress, the aim right from the start being for the black to come off and expose the red paint below, and the white base. This sense of progressing, never stopping, is the true essence of Murakami Saburo, and applies just as readily to his kami-yaburi work. Murakami also takes the deterioration of works that is taboo in art and overturns it in splendid fashion akin to a decisive strike in a traditional Japanese martial art. I suspect this is also what Kosugi-san liked about Murakami’s work. I too am a big fan of this sensation of sword splitting bamboo with one precise cut.

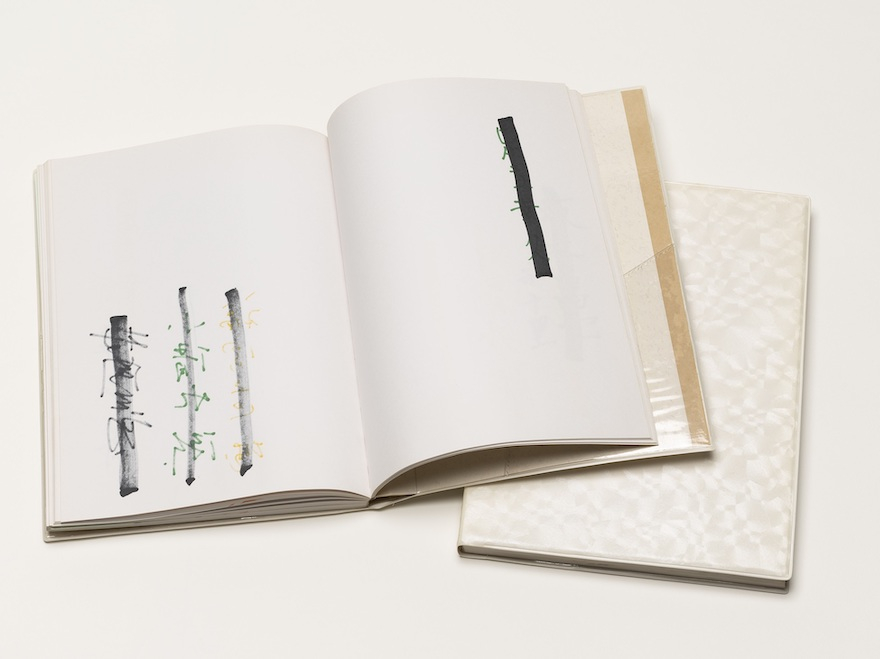

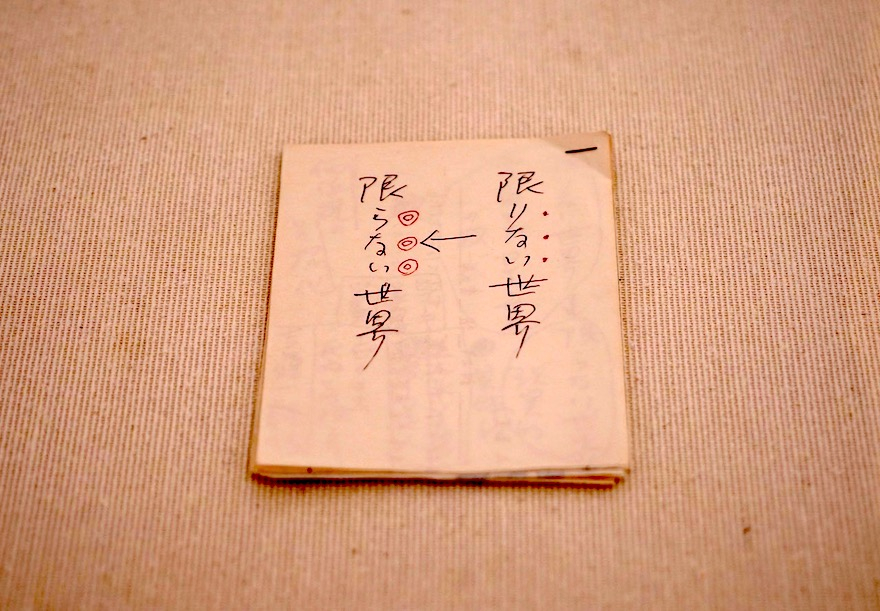

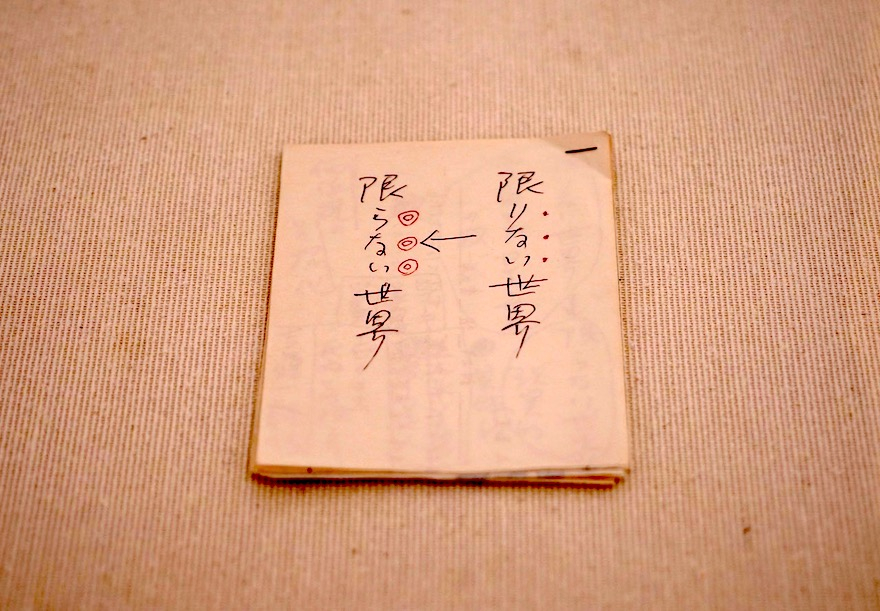

In the final room, the most interesting discovery for me was the record of solo shows by Murakami at small galleries in the 1970s. Here were Silence, in which one entered the gallery to find only a mute Murakami, communicating with visitors solely in writing, and Water, in which he moved water from a large bowl into another each time someone entered. What here at first appears a nonsensical action also seems to symbolize the daily movement of people by train to and from their workplaces. Then there was Displeasure by the Principle of Identity, in which the instant someone coming to the gallery signed the visitors’ book, Murakami would draw a black line through their entry. Which must be about as rude as it gets. How did people respond to this back then? One thing is certain: it would have been an unforgettable art experience for the spectator. I’m reminded of a work by Pierre Huyghe, a French artist about my age, in which he asks visitors their name at the entrance to the exhibition, and calls out those names one at a time, making the existence of the spectator for a moment part of the exhibition. Extinguishing and exposing the individual: for me anyway, the superimposing of today’s European conceptual art and Murakami’s idea from 50 years ago, like negative and positive images, was intriguing. Murakami apparently studied philosophy at university, and the notes he left behind do suggest a great deal of thinking from day to day, but I found it really interesting that in the gaps between, occasionally there would be these incredible ideas, leaps, explosions of a sort, with a haphazard, hell-bent quality. And in my view, that is precisely what art is.

In the final room, the most interesting discovery for me was the record of solo shows by Murakami at small galleries in the 1970s. Here were Silence, in which one entered the gallery to find only a mute Murakami, communicating with visitors solely in writing, and Water, in which he moved water from a large bowl into another each time someone entered. What here at first appears a nonsensical action also seems to symbolize the daily movement of people by train to and from their workplaces. Then there was Displeasure by the Principle of Identity, in which the instant someone coming to the gallery signed the visitors’ book, Murakami would draw a black line through their entry. Which must be about as rude as it gets. How did people respond to this back then? One thing is certain: it would have been an unforgettable art experience for the spectator. I’m reminded of a work by Pierre Huyghe, a French artist about my age, in which he asks visitors their name at the entrance to the exhibition, and calls out those names one at a time, making the existence of the spectator for a moment part of the exhibition. Extinguishing and exposing the individual: for me anyway, the superimposing of today’s European conceptual art and Murakami’s idea from 50 years ago, like negative and positive images, was intriguing. Murakami apparently studied philosophy at university, and the notes he left behind do suggest a great deal of thinking from day to day, but I found it really interesting that in the gaps between, occasionally there would be these incredible ideas, leaps, explosions of a sort, with a haphazard, hell-bent quality. And in my view, that is precisely what art is.

It was also interesting to learn that Murakami and Shiraga initially worked under the name Zero-kai (Zero Group), separate to Gutai, and were invited by Gutai later to join. The likes of Tanaka Atsuko and Kanayama Akira also seem to have been part of this Zero-kai, and now I have an inkling of why these four are some of my favorite people. They were people who endeavored to realize in their works the acts of moving, progressing, changing, and living. The title of this exhibition was “Unlimited World,” and it was a proclamation of freedom that continues to rapidly change and grow.

It was also interesting to learn that Murakami and Shiraga initially worked under the name Zero-kai (Zero Group), separate to Gutai, and were invited by Gutai later to join. The likes of Tanaka Atsuko and Kanayama Akira also seem to have been part of this Zero-kai, and now I have an inkling of why these four are some of my favorite people. They were people who endeavored to realize in their works the acts of moving, progressing, changing, and living. The title of this exhibition was “Unlimited World,” and it was a proclamation of freedom that continues to rapidly change and grow.

Shimabuku

Artist

https://shimabuku.net/top-en/ “Murakami Saburo: Unlimited World” was held from December 4, 2021 through February 6, 2022, at the Ashiya City Museum of Art and History.

https://ashiya-museum.jp/exhibition/16179.html

Murakami Saburo, Passage, 1956, at the Second Gutai Art Exhibition

Fusuma door paper that sparked Murakami’s “Kami-yaburi” performances (photo by Shimabuku)

Shiraga Kazuo and Murakami Saburo at their joint exhibition; courtesy the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka

From the archival footage of Exit (photo by Shimabuku)

Murakami Saburo, Work (detail), 1957; courtesy the Ashiya City Museum of Art and History

Murakami Saburo, Work (detail), 1957; courtesy the Ashiya City Museum of Art and History

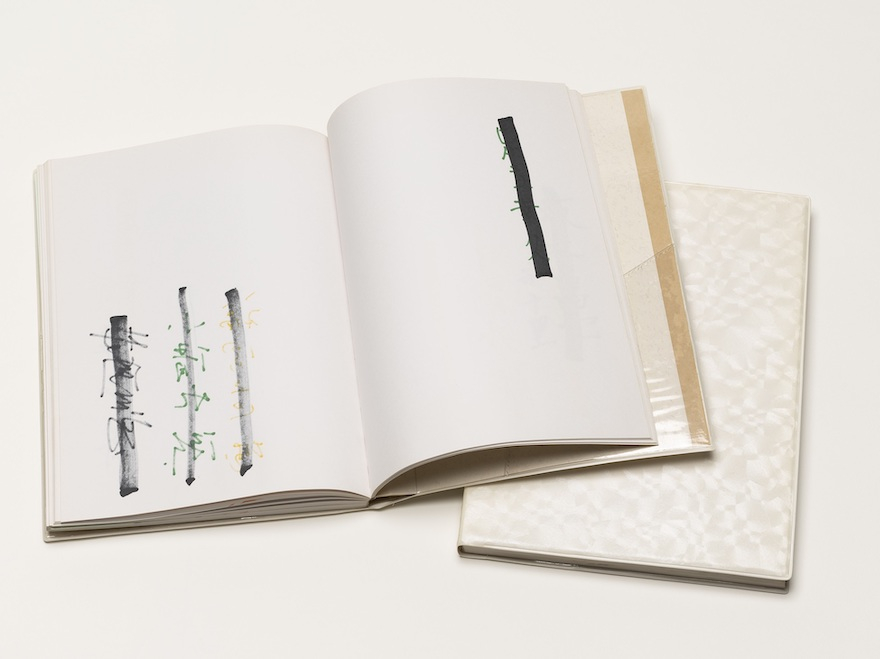

Guest book from Murakami Saburo’s exhibition “Displeasure by the Principle of Identity”; courtesy National Museum of Art, Osaka (photo by Fukunaga Kazuo)

Murakami’s note revising “Infinite World” to “Unlimited World” (photo by Shimabuku)

Shimabuku

Artist

https://shimabuku.net/top-en/ “Murakami Saburo: Unlimited World” was held from December 4, 2021 through February 6, 2022, at the Ashiya City Museum of Art and History.

https://ashiya-museum.jp/exhibition/16179.html