Review

The art and dynamic power of unending back-and-forth: Morimura Yasumasa’s Ningyo Joruri

By Yanagi Miwa

2022.04.05

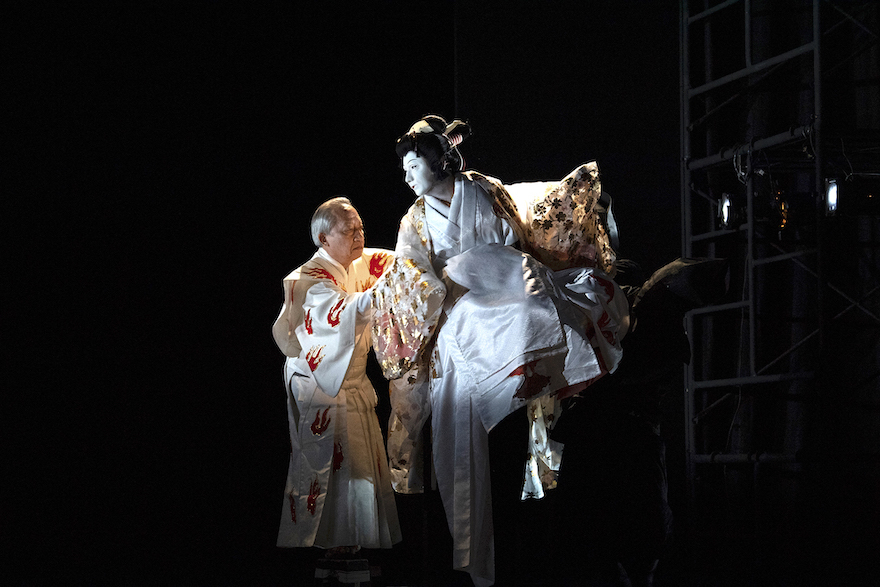

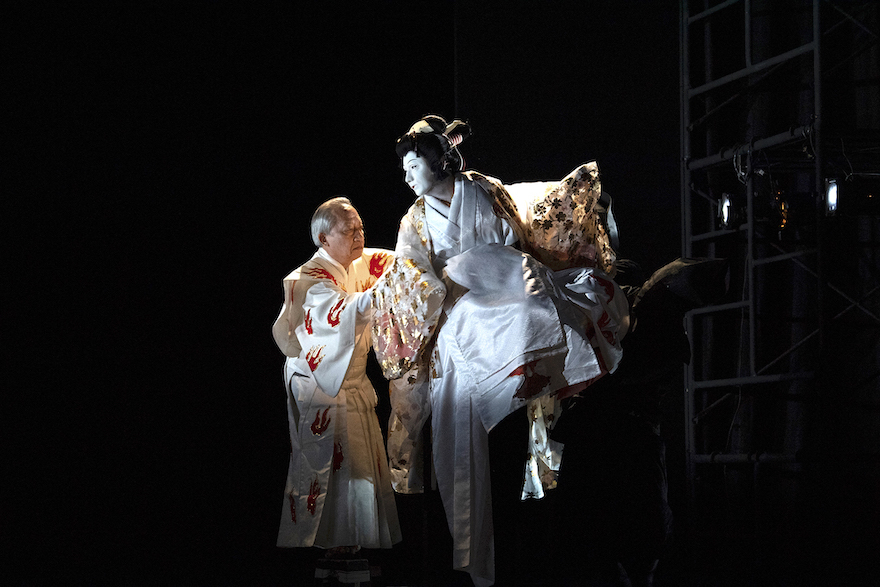

Ningyo Joruri was the perfect showcase for the versatile talents of Morimura Yasumasa. Morimura wrote the script (in the form known in puppet theater as yukahon), served as overall director of the show, and to top it all off, performed as a puppet.

Watching Ningyo Joruri reminded me of a small work of Morimura’s I acquired in the mid 1990s: a side-on polaroid photo of Morimura and a doppleganger doll, facing each other. In the center of the shot was the blank space separating the pair. How many times in the ensuing decades has Morimura shown us himself traversing back and forth across this divide?

Watching Ningyo Joruri reminded me of a small work of Morimura’s I acquired in the mid 1990s: a side-on polaroid photo of Morimura and a doppleganger doll, facing each other. In the center of the shot was the blank space separating the pair. How many times in the ensuing decades has Morimura shown us himself traversing back and forth across this divide?

I was also reminded of the actress whose body kept turning back to front, a character in a serialized novel published by Morimura during the same period, who fretted that the relentless flipping of her body “might become a habit!”

And here commenced yet another Morimura performance of reversal – human and puppet, this world and next – to the impassioned strains of shamisen and its joruri narration accompaniment.

A giant frame reminiscent of a Buddhist flame mirror installed onstage revolves at the climax of the performance. A prop built not to puppet but human dimensions, the frame recalls a chinowa kuguri grass hoop at a Shinto shrine. Showing both sides of this “mirror” simultaneously is one thing in a novel, photo or video, but to realize it live on stage requires command of something much larger. The weight and feel of the prop, the power and controls to work it, whether by hand or motor, the heat generated by all this “heavy work” explodes on the stage. Everything on stage acquires a vital warmth, giving it a corporeal quality. Percolating here is the slightly suspect but nostalgia-tinged, intoxicating scent of mass entertainment.

A giant frame reminiscent of a Buddhist flame mirror installed onstage revolves at the climax of the performance. A prop built not to puppet but human dimensions, the frame recalls a chinowa kuguri grass hoop at a Shinto shrine. Showing both sides of this “mirror” simultaneously is one thing in a novel, photo or video, but to realize it live on stage requires command of something much larger. The weight and feel of the prop, the power and controls to work it, whether by hand or motor, the heat generated by all this “heavy work” explodes on the stage. Everything on stage acquires a vital warmth, giving it a corporeal quality. Percolating here is the slightly suspect but nostalgia-tinged, intoxicating scent of mass entertainment.

In Ningyo Joruri the heroine O-kyo is transformed into an evil spirit, played by Morimura Yasumasa himself acting in ningyoburi fashion, that is, like a puppet. And a splendid job he makes of it. Ningyoburi, in which a character dances using the gestures of a puppet, is a special form of dramatic presentation, found in performing arts such as kabuki and traditional Japanese dance and said to have its origins in a fusion of actor and joruri narrative music back in the Genroku era. Especially fascinating are those scenes in which ningyoburi is performed by an actor, deliberately expressing in awkward puppet-like movements a person plunged into a frenzied state, stirred by violent emotions, for example in the piece “Yagura no Oshichi,” adapted from the story of a young girl who madly in love starts a devastating fire.

In Ningyo Joruri the heroine O-kyo is transformed into an evil spirit, played by Morimura Yasumasa himself acting in ningyoburi fashion, that is, like a puppet. And a splendid job he makes of it. Ningyoburi, in which a character dances using the gestures of a puppet, is a special form of dramatic presentation, found in performing arts such as kabuki and traditional Japanese dance and said to have its origins in a fusion of actor and joruri narrative music back in the Genroku era. Especially fascinating are those scenes in which ningyoburi is performed by an actor, deliberately expressing in awkward puppet-like movements a person plunged into a frenzied state, stirred by violent emotions, for example in the piece “Yagura no Oshichi,” adapted from the story of a young girl who madly in love starts a devastating fire.

Obviously, not every such instance of monogurui (as it is known) madness is choreographed as ningyoburi, but the attempt to overcome realism does ultimately arrive at the “puppet.” Presenting the body as mere vessel, moved by something, indicates to the audience that the body and spirit are separate. The role reversal by which a human copies the puppet that is supposed to copy a human is a perfect fit for Morimura.

An exuberant performance featuring music composed and played on shamisen by Tsuruzawa Seisuke, the gidayu recitation of Takemoto Oritayu, and puppetry of Kiritake Kanjuro is what brings about the miracle of this reversal. Doubtless it is in the skills of these consummate classical performing art professionals that Morimura identified the technique of making the body a vessel to transcend the domain of the self; because there is unmistakably something magical in the singing, music and dance of traditional performing art entertainment.

Kagura dance, odori nenbutsu, noh, kabuki, ningyo joruri puppetry: all retain vestiges of a time before the separation of religion and performing arts, and contain skills that take people out of themselves. These are handed down as kata, so are not always immediately obvious. Into this potent mix leaps Morimura, bodily, hitting the ground running. Leaping into and merging with distant gods and buddhas, giving them a flesh and blood presence, is part of the performer’s art. But Morimura Yasumasa is the artist who not only “merges” but always takes such great care to offer up the process of that “leap” for our delectation.

Kagura dance, odori nenbutsu, noh, kabuki, ningyo joruri puppetry: all retain vestiges of a time before the separation of religion and performing arts, and contain skills that take people out of themselves. These are handed down as kata, so are not always immediately obvious. Into this potent mix leaps Morimura, bodily, hitting the ground running. Leaping into and merging with distant gods and buddhas, giving them a flesh and blood presence, is part of the performer’s art. But Morimura Yasumasa is the artist who not only “merges” but always takes such great care to offer up the process of that “leap” for our delectation.

Transcending meta techniques to ask what a painting is, from within a painting, what a puppet is, from within a puppet show; endlessly repeating the back-and-forth jumping in and returning of chinowa kuguri, yet with that circle not confined to the same place; one cannot help but admire the long, fruitful journey taken here, steadfast and fearless, resembling a three-dimensional spiral expanding infinitely into space. But for the realm of Morimura Yasumasa to materialize on this new frontier, with the artist boldly tackling not just theater but a traditional performing art, requires the abilities of a specialist who knows the stage inside and out.

Ago Satoshi has already taken on a stage production role and guided to fruition five of Morimura’s works, starting with Nippon Cha Cha Cha! Building a theater space in an irregular, non-theatrical location, and getting the people gathered there from other disciplines to work together, is no easy task. Collaboration between people in different fields can be a particular source of discord, and the best creating occurs in settings where those engaged in traditional arts take the lead in creative inventiveness and ingenuity. In this show, contrary to what one might assume from the small number of puppets, and size of the temporary stage assembled at the museum, a large number of people end up jostling around in the darkness, hidden from the audience, and the director who keeps this Morimura theater up and running, with its puppeteers, prompter and stagehands, optimizing the performance of each while also ensuring their safety, makes a massive contribution to the show’s success. In complete contrast, the “unmanned theater” in Morimura’s “My Self-Portraits as a Theater of Labyrinths,” which started at the Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art the week after this puppet piece, is an automated show in Ago’s signature automata-heavy style, consisting primarily of recorded sound. Considering the complete absence of any material such as puppets or people, this work that succeeded in bringing vividly to life a small, empty tatami room using just Morimura’s narration, video and lighting, was indeed magical.

As Washida Kiyokazu and robotics engineer Ishiguro Hiroshi noted in their conversation/book, Ikirutte nanyaro ka? (What is living?), “Ecstasy is the moment when a human sheds human boundaries; separating from those boundaries allows them to acquire different identities, and moving back and forth across these boundaries is what it means for a human to be alive.” And indeed the human wish to expand the human domain, or arrive at a nonhuman level, is often fulfilled in literature, music, art, and the performing arts. Sometimes it happens by chance, even when it was not the creator’s intention. Needless to say this occurs in expression with a temporal dimension such as music, theater and film, and obviously also in painting. In waka poetry, the writer can be deliriously in love in the first three lines, and in the last two, gaze up at the moon and suddenly attain a state of sokuten-kyoshi, that is, relinquishing their ego and yielding to heaven and nature.

The ecstasy of transcending boundaries concealed by some artists, the rapture of moving back and forth, are things Morimura has expressed in forms visible to others since fairly early in his career. This has at times taken three-dimensional or multilayered form, manifesting as art in a surprisingly large number of ways. Transcending boundaries then returning to the self, in a robust circular system in which he never just “leaves” but always returns; Morimura tirelessly keeps this system going round, serving as its source of dynamic power, to keep on producing his self-portraits.

The ecstasy of transcending boundaries concealed by some artists, the rapture of moving back and forth, are things Morimura has expressed in forms visible to others since fairly early in his career. This has at times taken three-dimensional or multilayered form, manifesting as art in a surprisingly large number of ways. Transcending boundaries then returning to the self, in a robust circular system in which he never just “leaves” but always returns; Morimura tirelessly keeps this system going round, serving as its source of dynamic power, to keep on producing his self-portraits.

Yanagi Miwa

Artist/theater director

*Ningen Joruri was performed at the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka auditorium on February 26 and 27, 2022. This review was written based on the 16:00 performance on Sunday, February 27.

I was also reminded of the actress whose body kept turning back to front, a character in a serialized novel published by Morimura during the same period, who fretted that the relentless flipping of her body “might become a habit!”

And here commenced yet another Morimura performance of reversal – human and puppet, this world and next – to the impassioned strains of shamisen and its joruri narration accompaniment.

Obviously, not every such instance of monogurui (as it is known) madness is choreographed as ningyoburi, but the attempt to overcome realism does ultimately arrive at the “puppet.” Presenting the body as mere vessel, moved by something, indicates to the audience that the body and spirit are separate. The role reversal by which a human copies the puppet that is supposed to copy a human is a perfect fit for Morimura.

An exuberant performance featuring music composed and played on shamisen by Tsuruzawa Seisuke, the gidayu recitation of Takemoto Oritayu, and puppetry of Kiritake Kanjuro is what brings about the miracle of this reversal. Doubtless it is in the skills of these consummate classical performing art professionals that Morimura identified the technique of making the body a vessel to transcend the domain of the self; because there is unmistakably something magical in the singing, music and dance of traditional performing art entertainment.

Transcending meta techniques to ask what a painting is, from within a painting, what a puppet is, from within a puppet show; endlessly repeating the back-and-forth jumping in and returning of chinowa kuguri, yet with that circle not confined to the same place; one cannot help but admire the long, fruitful journey taken here, steadfast and fearless, resembling a three-dimensional spiral expanding infinitely into space. But for the realm of Morimura Yasumasa to materialize on this new frontier, with the artist boldly tackling not just theater but a traditional performing art, requires the abilities of a specialist who knows the stage inside and out.

Ago Satoshi has already taken on a stage production role and guided to fruition five of Morimura’s works, starting with Nippon Cha Cha Cha! Building a theater space in an irregular, non-theatrical location, and getting the people gathered there from other disciplines to work together, is no easy task. Collaboration between people in different fields can be a particular source of discord, and the best creating occurs in settings where those engaged in traditional arts take the lead in creative inventiveness and ingenuity. In this show, contrary to what one might assume from the small number of puppets, and size of the temporary stage assembled at the museum, a large number of people end up jostling around in the darkness, hidden from the audience, and the director who keeps this Morimura theater up and running, with its puppeteers, prompter and stagehands, optimizing the performance of each while also ensuring their safety, makes a massive contribution to the show’s success. In complete contrast, the “unmanned theater” in Morimura’s “My Self-Portraits as a Theater of Labyrinths,” which started at the Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art the week after this puppet piece, is an automated show in Ago’s signature automata-heavy style, consisting primarily of recorded sound. Considering the complete absence of any material such as puppets or people, this work that succeeded in bringing vividly to life a small, empty tatami room using just Morimura’s narration, video and lighting, was indeed magical.

As Washida Kiyokazu and robotics engineer Ishiguro Hiroshi noted in their conversation/book, Ikirutte nanyaro ka? (What is living?), “Ecstasy is the moment when a human sheds human boundaries; separating from those boundaries allows them to acquire different identities, and moving back and forth across these boundaries is what it means for a human to be alive.” And indeed the human wish to expand the human domain, or arrive at a nonhuman level, is often fulfilled in literature, music, art, and the performing arts. Sometimes it happens by chance, even when it was not the creator’s intention. Needless to say this occurs in expression with a temporal dimension such as music, theater and film, and obviously also in painting. In waka poetry, the writer can be deliriously in love in the first three lines, and in the last two, gaze up at the moon and suddenly attain a state of sokuten-kyoshi, that is, relinquishing their ego and yielding to heaven and nature.

Yanagi Miwa

Artist/theater director

*Ningen Joruri was performed at the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka auditorium on February 26 and 27, 2022. This review was written based on the 16:00 performance on Sunday, February 27.