This Wolfgang Tillman’s retrospective was postponed for 18 months due to the pandemic, and to that extent it was prepared carefully over time. As if returning to his beginnings, the artist splendidly retraced his steps over the last 30 years using the very early presentation approach that gave rise to so many imitators: installations in which works of different sizes are scattered around the entire museum space like a constellation, or an electronic music score.

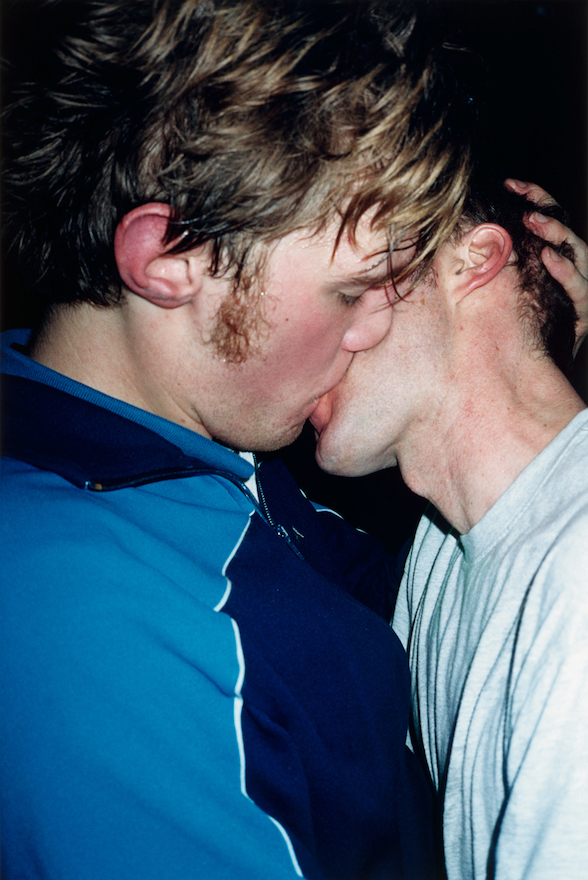

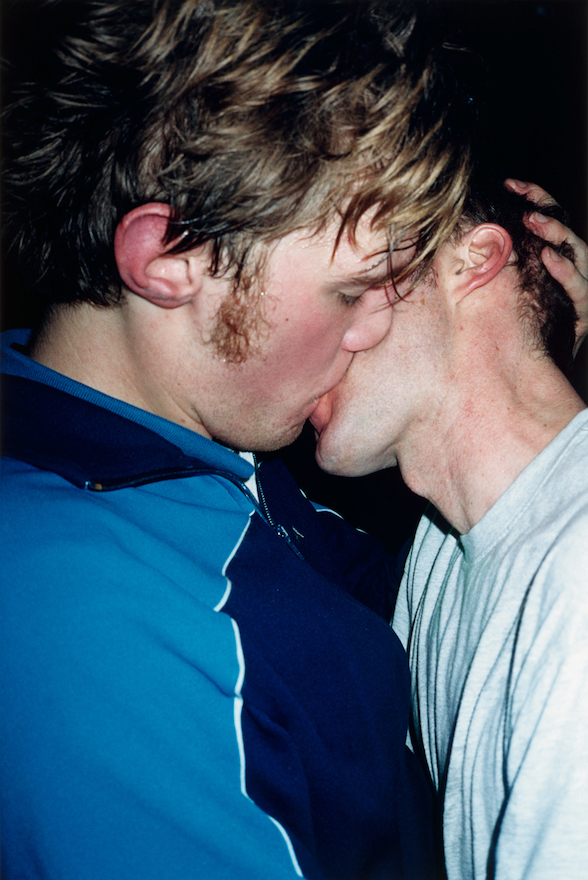

1 The spirit of borderless freedom that swept through Europe for several years after the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the rave culture that so enraptured Tillmans; the love affair with the painter Jochen Klein, whom he met during this time; the two contracting HIV and Jochen dying of AIDS-related complications; the “Concorde” series as memento mori;

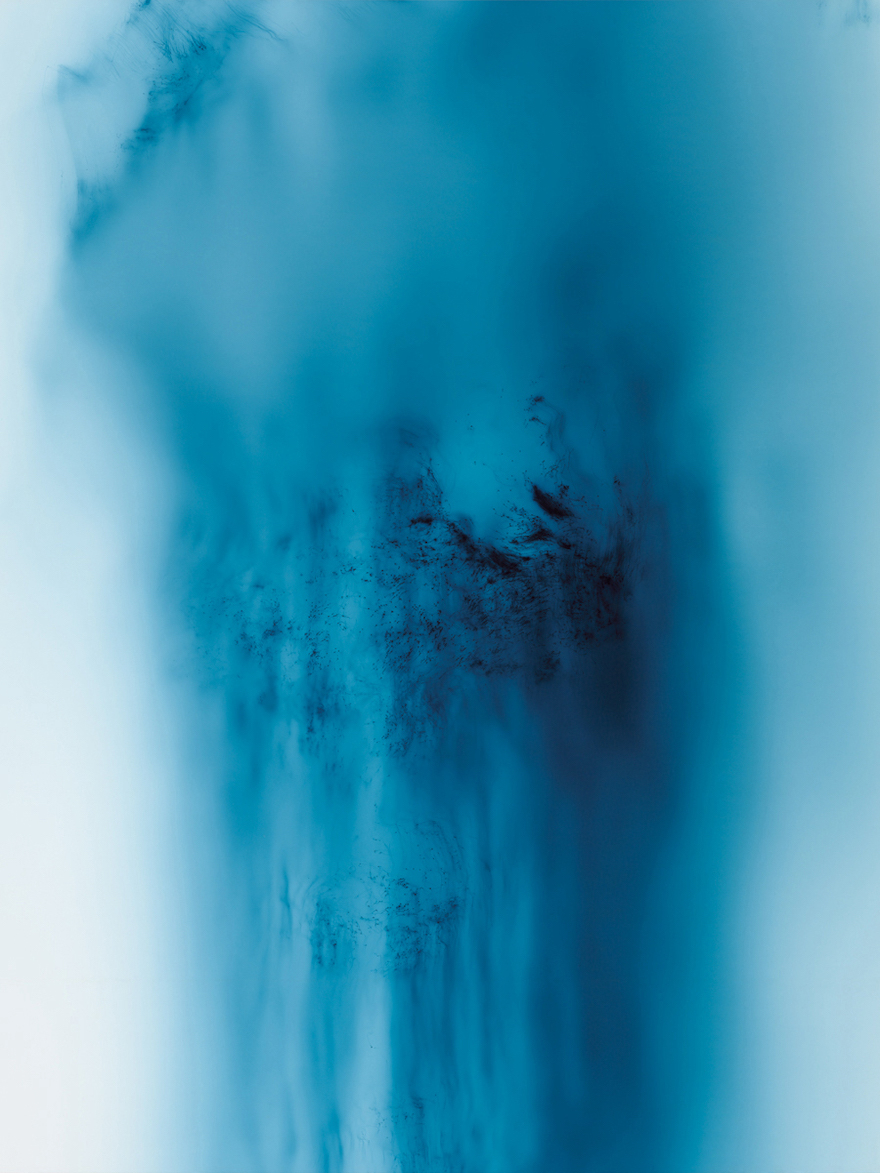

I don’t want to get over you (2000), an abstract photo stemming from Tillmans’ denial of Jochen’s death (not being able to take new photos of him ever again);

2 a sense of helplessness in the face of neo-liberalism and globalization; the wars and terrorism occurring all over the world; Truth Study Center, a project in opposition to the flood of information and images;

3 turning to digital photography, actively accepting the capabilities of digital technology (high resolutions far exceeding the naked eye, light sensitivity, printing technology), and producing

Neue Welt, which vividly captured fleeting, local scenes all over the world after the passage of the wave of globalization against backdrops of cosmic space-time (solar and lunar eclipses, the transit of Venus across the Sun, the “great” conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn);

4 Brexit, which completely frustrated Tillmans, moving to Berlin, the rise of Alternative für Deutschland and the Ukrainian crisis; Tillmans’ inclination towards music and video demonstrating a patent nostalgia for ’80s technopop; and at the end of the exhibition, in front of a scene of morning sun shining on the remnants of an all-night (30-year-long?) party, two towers of mirrors erected in such a way that those who step between them are reflected infinitely in both directions (past and future?).

Installation view of Wolfgang Tillmans: To look without fear, on view at The Museum of Modern Art, New York from September 12, 2022 through January 1, 2023. Photo: Emile Askey

The Cock (kiss) (2002). Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Venus transit (2004). Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

So direct and beautiful it calls to mind the proverb “A bird taking wing does not leave muddy water behind,” this solo exhibition is also like an autobiography written prematurely by the 54-year-old artist. If we recall Tillmans’ activities over the last decade or so, which has seen him continue to actively push back as an artist-activist in the face of a weakening EU, retreating democracy buffeted by the waves of post-truth politics and an awareness of national borders and barriers being restored, then one might even be inclined to suspect that he is using the symbolic place that is New York’s Museum of Modern Art to gracefully bid farewell to the art world.

5 Neither is it a wonder that the reviewer at

The New York Times described it as “One of the saddest museum exhibitions I have ever attended.” “Those late, sweaty ’90s nights: then, we were sure we had met the chronicler of a new millennium’s freedoms. What if Tillmans was instead a harbinger of the artist as entrepreneur of the self, and of how we would all go on posting pictures even as our misfortunes piled up offscreen?”

6 The term “entrepreneur of the self” calls to mind Foucault, and while the words are chosen carefully, the point seems to be that though Tillmans has achieved distinction, crowned by a retrospective at MoMA, the times have now caught up with him and he is nearing the end of his career. But even though this could be the bittersweet first impression this retrospective gives, it is not how it should be understood.

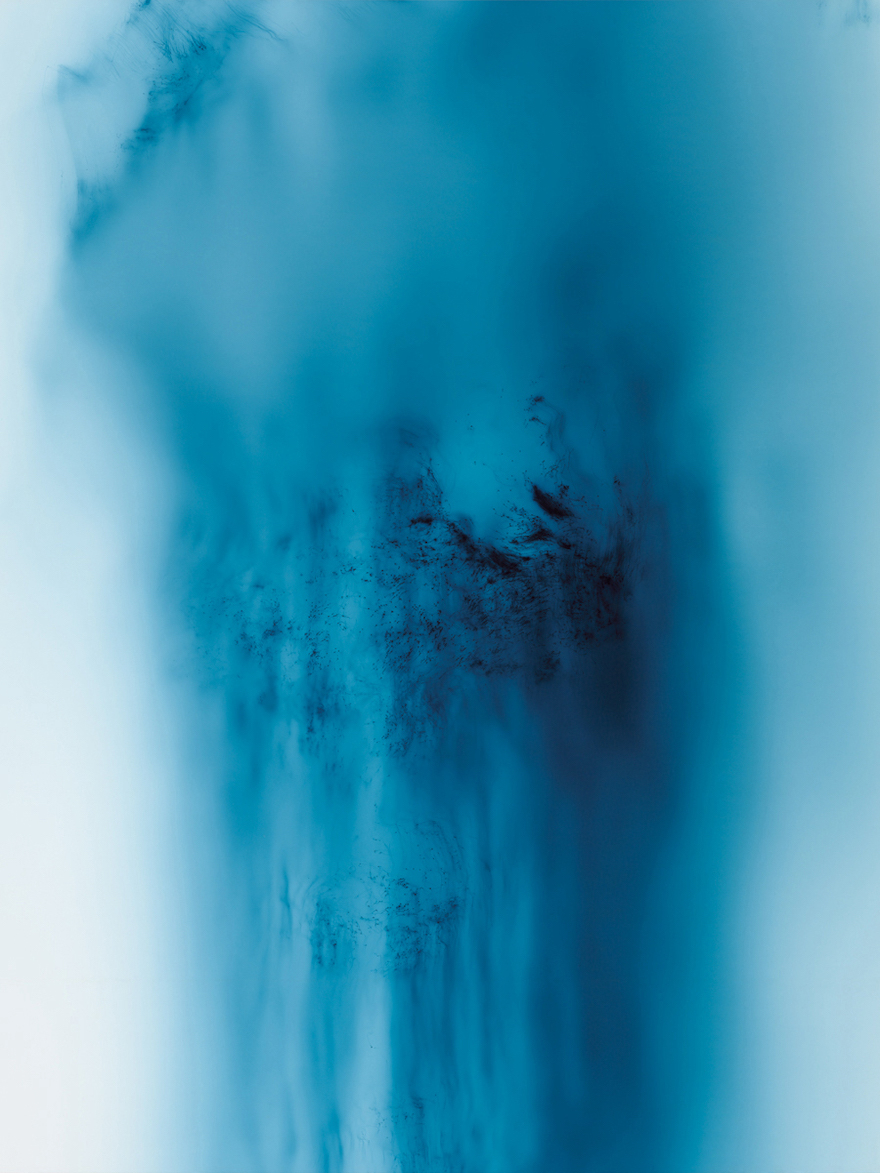

Freischwimmer 230 (Free Swimmer 230, 2012). Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Concrete Column III (2021). Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

What I feel first of all is that American critics have no sense of being personally involved in the crisis that is beginning to envelop Europe (the revival of fascism). Tillmans’ politicization over the last ten years or so—the knowingly uncool title of the Truth Study Center,

the naïve posters urging people to vote in the EU membership referendum, the deliberate uncoolness of the Righteousness with a capital R of going as far as bringing up the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights—stems directly from his sense of crises as someone personally involved.

7 It cannot be helped that people in the New World who do not share the uneasiness concerning the return of the dark past that people in the Old World probably feel viscerally cannot understand Tillmans’ political art—which began with “Freedom from the known” (MoMA-PS1, 2006) and has been developed extensively by way of digital photography since

Neue Welt (2012)—and can only view the photos of street demonstrations and the AIDS Foundation as “self-righteousness,” but the responsibility for this should not be borne by the artist.

Lutz & Alex sitting in the trees (1992). Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Next, the old-fashioned argument that Tillmans’ photos are indistinguishable from snapshots taken by amateurs or today’s Instagram photos is due to viewers recognizing in them nothing but a non-style style, which is to say a staged naturalness. However, looking at the photos Tillmans took for use in advertising, it is clear that on the contrary their essence lies in the naturalness of their unnaturalness. For example, at a glance,

Lutz & Alex sitting in the trees (1992), here presented in an extra-large size, does not look like a natural photo, and judging from the direction of Alex’s gaze, the photographer is on top of a tall stepladder or has climbed a nearby tree. A kind of intimacy arises from the staging in which childhood friends are stripped naked and made to pose in a tree wearing nothing but raincoats, but because this is positioned not at the level of reality (all the participants behaving honestly) but at the level of staging (all understand it is acting), the staged unnaturalness turns into naturalness.

Silver 152, chromogenic print, 21 5/16 × 25 1/4″ (54.2 × 64.2 cm) (2013). Image courtesy of the artist, David Zwirner, New York / Hong Kong, Galerie Buchholz, Berlin / Cologne, Maureen Paley, London

Moreover, Tillmans’ photographs are not complete as individual works; rather, they resonate or are continuous with other groups of photos through equivalency (the superficial feeling that pervades the captured images, e.g. elasticity, insertion, protrusion, luster),

8 through repetition of the same image in different sizes,

9 through the relationship between parts and the whole

10 or through comparisons of analog and digital versions of the same motifs.

11 The abstract photos that appeared following Jochen’s death developed as both pure expressions of equivalency and meta-photography-like works concerning analog photography (

the “paper drop” series and

Studio Light as familiar pinhole phenomena, photographs as photochemical change itself, i.e. “Silver”), and are in the process of developing further due to the kind of digital technology mentioned above (e.g. the massive “Silver” series). Once one notices the multilayered resonances among the groups of images spread across the entire exhibition, the story of “decline from the brilliant ’90s” becomes all too unilinear and too closely aligned with the life of the artist himself. After all, this is the second exhibition looking back in detail on his own past (the first, “If one thing matters everything matters” [Tate, 2003], cataloged in chronological order all of Tillmans’ works going back as far as the astronomical photographs he took at age ten). Wolfgang Tillmans is an artist who periodically settles the past and becomes empty. He does this not to think back on a lost past but to free himself from the past. The symphony played by the groups of images is neither a song of joy nor a requiem.

——————————–

1. For example, Karlheinz Stockhausen’s score STUDIE II (1954) (detail).

2. See Shimizu Minoru, “Memento mori: Tillmans chūshō shashin no tanjō” [The Birth of Tillmans’ abstract photographs], in Shimizu Minoru, Hibikore shashin [Every day photographs] (Tokyo: Gendai Shicho Shinsha, 2009).

3. See Shimizu Minoru, “Yuganda shikakkei: Wolfgang Tillmans to shashin no kūkan-sei” [Distorted rectangles: Wolfgang Tillmans and the spatiality of photography], in ibid.

4. See Shimizu Minoru, “Rifurein to sanshu: Wolfgang Tillmans no ‘desukutopputaipu’ reiauto” [Refrain and dissemination: Wolfgang Tillmans’ ‘desktop-style’ layout], in Wolfgang Tillmans (Tokyo: Bijutsu Shuppansha, 2014).

5. “Tillmans said he had met with lawmakers to discuss standing for the Bundestag, Germany’s lower house of Parliament.” Now 54, “he has been thinking, ‘Maybe it’s time to take responsibility.’ [From the perspective of socially engaged practice] [p]eople are ‘more and more into politics,’ he said, ‘but no one is going into politics.'”[Bracketed comment mine] Matthew Anderson, “Wolfgang Tillmans: Older, Wiser, Cooler,” The New York Times, August 29, 2022; updated September 1, 2002.

6. Jason Farago, “Disappearing World of Wolfgang Tillmans,” The New York Times, September 8, 2022; a review published with god-like speed immediately after the press preview!

7. This deliberate uncoolness is reminiscent of Takahashi Yuji’s transformation to the Suigyu-Gakudan [Water Buffalo Band].

8. See Shimizu Minoru, “Wolfgang Tillmans: The Art of Equivalence” in Wolfgang Tillmans truth study center (Cologne: Taschen, 2005).

9. In this exhibition, Room 1 Wall 1-4 Springer 1987 → Room 11 Wall 2-2 Springer 1987. The room and wall numbers are as printed on the map in the exhibition pamphlet.

10. There are numerous examples, including Room 1 Wall 2-15 Adam redeye 1991 → Wall 2-17 Adam redeye (photocopy) 1991.

11. Good examples include the photos of the night sky and nightscapes, as well as the photos of club interiors late at night. Unlike the analog versions of the former, with the digital versions (from Room 7 onwards), the photographer was not looking at such scenes with the naked eye at the time the photos were taken. These are scenes that first began to exist when they became photographic images (e.g. Room 7 Wall 7-9 Munuwata sky 2011, Room 8 Wall 4-6 The Spectrum/Dagger 2014, Room 11 Wall 4-5 crossing the international date line 2020).

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University.

Wolfgang Tillmans “To look without fear” is being held at

the Museum of Modern Art, New York, through January 1, 2023.