Op-ed column

On the removal of Okazaki Kenjiro’s work from Faret Tachikawa

Text by Fukunaga Shin

2022.11.01

News reached me, totally out of left field, that the work by Okazaki Kenjiro might be removed from Faret Tachikawa. I made inquiries with the artist, with Faret Tachikawa art planners Kitagawa Fram / Art Front Gallery, and with the Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C. shopping center, where the work is installed,*1 and was informed that the sculpture will indeed be removed, the reason being that as of January 31 the Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C. department store precinct will close, and following construction work in autumn, a (provisionally titled) “Place du Marché” set up that will have no place for Okazaki’s creation. So the Faret Tachikawa Art management committee and Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C. are currently exploring their options with a view to removing and/or relocating the work. A start date for the new construction has yet to be finalized, but temporary fences will be going up around the site from February 1, so if you have the chance, try to go see the work in person before then.

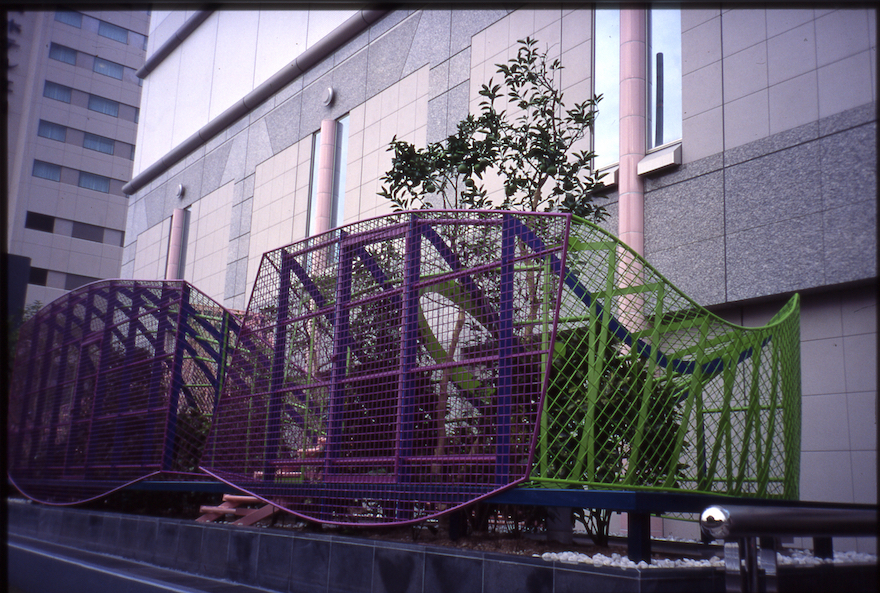

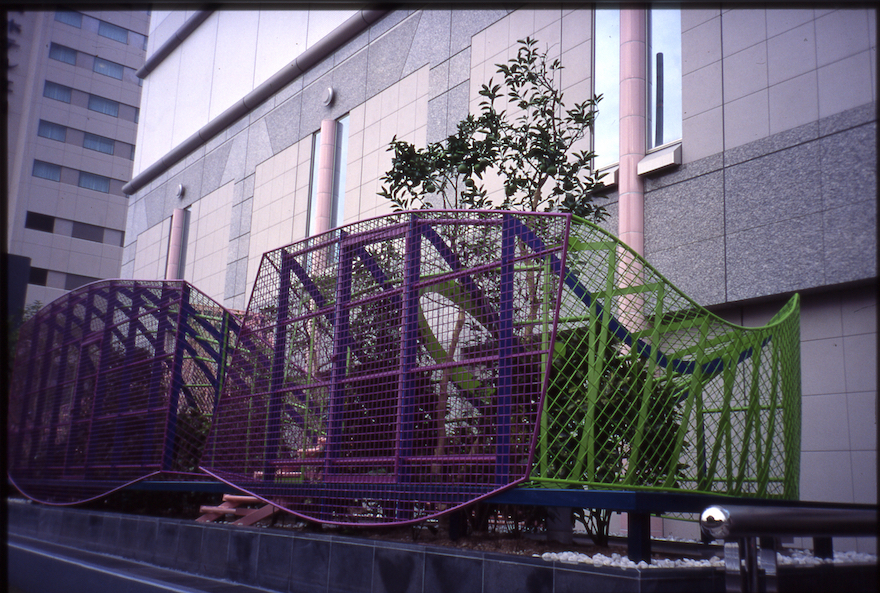

Mount Ida – The boy Paris is still shepherding (1994) by the then 39-year-old Okazaki Kenjiro is a work of public art at Faret Tachikawa. It is a fence located at the back of the Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C. building, serving as a cover for the underground parking ventilation outlet. Inside it are various plantings. Faret Tachikawa unfolds mainly in a commercial redevelopment around Tachikawa Station, and consists of 109 works of art each serving a dual purpose as a bench, car stop or the like, installed in a manner that incorporates the surrounding environment. Foot traffic links the individual works, these loosely curated connections forming a large part of the project’s allure.*2 Obviously, the absence of one work will impact significantly on the whole project. Okazaki’s work, moreover, serves as the foundation stone of the Faret Tachikawa concept (with part of the actual project concept apparently being based on an idea of Okazaki’s). There is no denying that Faret Tachikawa occupies an important place in Japan’s public art history. Removing a work from a project like that takes quite some nerve; it certainly creates a huge problem. One that deserves to be addressed in a public forum.*3

Discussions concerning removal did take place between owners of the work Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C., and the Faret Tachikawa Art management committee. The latter is the organization that carries out maintenance at Faret Tachikawa. Art Front Gallery served as a go-between, finding out what the artist thought, and relaying that, and the issue was addressed specifically on about six separate occasions between mid-June and October. The reality is, an owner-instigated proposal to remove a work is hard to oppose, and with Mount Ida failing to fit the owner’s plans for their commercial property, there seems to have been almost no chance from the start of it being left in situ. This being the case, talks soon shifted to studying the possibilities for “relocation.” On this topic the artist also made a number of suggestions in writing via Art Front Gallery, including concerning the conditions under which his copyright on the work would be protected if it were dismantled, for example by 3D data. Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C. has indicated it is happy with this. Word has it they are currently investigating new locations for the work, and although a suitable spot has not been found in Tachikawa, it looks like dismantling can be avoided (a caution against complacency though: if no new location can in fact be found, removal will indeed mean dismantling).

Mount Ida – The boy Paris is still shepherding (1994) by the then 39-year-old Okazaki Kenjiro is a work of public art at Faret Tachikawa. It is a fence located at the back of the Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C. building, serving as a cover for the underground parking ventilation outlet. Inside it are various plantings. Faret Tachikawa unfolds mainly in a commercial redevelopment around Tachikawa Station, and consists of 109 works of art each serving a dual purpose as a bench, car stop or the like, installed in a manner that incorporates the surrounding environment. Foot traffic links the individual works, these loosely curated connections forming a large part of the project’s allure.*2 Obviously, the absence of one work will impact significantly on the whole project. Okazaki’s work, moreover, serves as the foundation stone of the Faret Tachikawa concept (with part of the actual project concept apparently being based on an idea of Okazaki’s). There is no denying that Faret Tachikawa occupies an important place in Japan’s public art history. Removing a work from a project like that takes quite some nerve; it certainly creates a huge problem. One that deserves to be addressed in a public forum.*3

Discussions concerning removal did take place between owners of the work Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C., and the Faret Tachikawa Art management committee. The latter is the organization that carries out maintenance at Faret Tachikawa. Art Front Gallery served as a go-between, finding out what the artist thought, and relaying that, and the issue was addressed specifically on about six separate occasions between mid-June and October. The reality is, an owner-instigated proposal to remove a work is hard to oppose, and with Mount Ida failing to fit the owner’s plans for their commercial property, there seems to have been almost no chance from the start of it being left in situ. This being the case, talks soon shifted to studying the possibilities for “relocation.” On this topic the artist also made a number of suggestions in writing via Art Front Gallery, including concerning the conditions under which his copyright on the work would be protected if it were dismantled, for example by 3D data. Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C. has indicated it is happy with this. Word has it they are currently investigating new locations for the work, and although a suitable spot has not been found in Tachikawa, it looks like dismantling can be avoided (a caution against complacency though: if no new location can in fact be found, removal will indeed mean dismantling).

While taking my hat off to those putting in all this effort, I have a couple of sticking points with the whole proceedings.

The first is the dearth of information. Faret Tachikawa has almost mythical status in Japanese public art, and for one of its constituent elements—one of its works—to no longer be there, is a pretty big deal. Information on this change should have been made widely available early on. But no information was disseminated at all. I just happened to hear from someone involved that “it looks unfortunately like Mount Ida‘s going to be removed” (early October), and surprised, asked the artist about it. Why has nothing been said? It would seem because ultimately, there has been no proper consensus around the removal. In the aforementioned discussions, matters are proceeding on the basis of de facto agreement, but because a formal decision has not been made, it would seem no information can be released externally. Thus there is a risk that information will only be made available immediately prior to the work being carted off. Public art is, as the name suggests, public, and not merely “property.” The owner is not the only party with a say in its fate, and for almost thirty years Mount Ida has been integral to the environment, a familiar feature in countless lives. It was designed specifically as a fence for the air vent, so if “relocated” would lose one of its vital elements: that of also having a practical purpose. If only we had known about all this much earlier: for the sake of those wanting to see it before it is relocated, and of any Faret Tachikawa fans or locals wanting to express their opposition to its removal.

My other issue with this is a concern that coordination between the artist, and Art Front Gallery serving as the middleman, may be less than ideal. I spoke to the artist himself on the phone on October 16, and on that occasion, though touching on the possibility of the work being dismantled, Okazaki told me that this would mean accepting breaking the work, creating a dangerous precedent, so he could not readily OK such an operation. In other words, the artist was under the impression that things could still be halted, that removal/dismantling or relocation could be overturned. Hardly surprising when no formal agreement has been reached. The person at Art Front Gallery however didn’t seem to feel revoking the work’s removal was a viable option. This despite the fact that no “consensus” has been reached. Art Front Gallery has consistently taken the attitude that there will be no backtracking on Mount Ida‘s removal unless the owner decides to do so, and told me on the phone that “we are only observers” and “our position is neutral.” (Neutral? Aren’t you the lot who did the art planning?) AFG’s strong assertion of Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C.’s ownership rights, while saying nothing in particular about copyright, did not sit well with me either. It seems to have taken my intervention (?) for them to even notice the difference between their perception of the matter, and that of the artist, and one couldn’t help feeling that artist and art planners were not exactly in lockstep here.

Okazaki’s sculpture was conceived as an area of plantings or garden inaccessible to humans, but accessible to birds, cats, insects etc. (plants were specifically chosen that birds would peck at). The branches of trees covered in summer foliage protrude from the fence, altering the strangely twisted and severed form created by the artist. Inadvertently invalidating the cut-surface shapes as if soothing a wound, the trees are a lovely sight. But that sight will no longer be seen. (Will the plants be “relocated” as well? Will the animals just be abandoned?) Okazaki said Mount Ida was for animals, but it has plenty for humans too. Whether for relaxing, eating lunch, napping in the sun, or as a rendezvous point, people really love this place, and surely it is the perfect fit for a “(provisionally-titled) Place du Marché.” There could be no “warmer” place from a commercial viewpoint either. Just leave it alone.

——————————–

*1 I emailed the artist on October 15, then as written here, called him, subsequently emailing back and forth several times, and speaking on the phone once more. On October 18 I sent four questions to Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C. via their online inquiry form, and on the 20th received a reply from Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C. owner/operator Toshin Development Co., Ltd. Basically the same questions were sent on the same day, the 18th, to Art Front Gallery through their website, then on the 21st I received a call from a member of staff who generously spoke with me for over an hour. “On the removal of Okazaki Kenjiro’s work from Faret Tachikawa” is based on these conversations. Allow me here to thank those who took the time to talk with me.

*2 According to the website the official title is “FARET Tachikawa Art,” but it is also often referred to as the Faret Tachikawa Art Project. Most generally though, it is known simply as “Faret Tachikawa.” The author has written about Faret Tachikawa previously, including in the REALKYOTO blog that preceded this column, ie “Faret Tachikawa turns 21”.

*3 In his book Faret Tachikawa Public Art Project: Art Transforms a Base Town (Gendai Kikakushitsu, 2017) Kitagawa Fram notes that when it comes to the remodeling or demolition of buildings in the complex, in order to avoid unilateral decisions by the owner around the preservation or removal of any artworks installed on the site, “such decisions are made through discussions between the owner, artist and planners” (in this case Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C. and Okazaki Kenjiro and Kitagawa Fram/Art Front Gallery/the Faret Tachikawa Art management committee). Kitagawa’s book takes a fascinating, in-depth look at the origins of Faret Tachikawa, including the financial aspects of the project. Its embattled art planner, Kitagawa, in his late 40s at the time, was exploring how to inject fresh ideas, and a totally new concept, into the hidebound field of public art. This book gives an insight into some of his ideas, and is essential reading for any aspiring curator. I think this would be a good opportunity for Kitagawa himself to reacquaint himself with its contents.

——————————–

Fukunaga Shin

Novelist

While taking my hat off to those putting in all this effort, I have a couple of sticking points with the whole proceedings.

The first is the dearth of information. Faret Tachikawa has almost mythical status in Japanese public art, and for one of its constituent elements—one of its works—to no longer be there, is a pretty big deal. Information on this change should have been made widely available early on. But no information was disseminated at all. I just happened to hear from someone involved that “it looks unfortunately like Mount Ida‘s going to be removed” (early October), and surprised, asked the artist about it. Why has nothing been said? It would seem because ultimately, there has been no proper consensus around the removal. In the aforementioned discussions, matters are proceeding on the basis of de facto agreement, but because a formal decision has not been made, it would seem no information can be released externally. Thus there is a risk that information will only be made available immediately prior to the work being carted off. Public art is, as the name suggests, public, and not merely “property.” The owner is not the only party with a say in its fate, and for almost thirty years Mount Ida has been integral to the environment, a familiar feature in countless lives. It was designed specifically as a fence for the air vent, so if “relocated” would lose one of its vital elements: that of also having a practical purpose. If only we had known about all this much earlier: for the sake of those wanting to see it before it is relocated, and of any Faret Tachikawa fans or locals wanting to express their opposition to its removal.

My other issue with this is a concern that coordination between the artist, and Art Front Gallery serving as the middleman, may be less than ideal. I spoke to the artist himself on the phone on October 16, and on that occasion, though touching on the possibility of the work being dismantled, Okazaki told me that this would mean accepting breaking the work, creating a dangerous precedent, so he could not readily OK such an operation. In other words, the artist was under the impression that things could still be halted, that removal/dismantling or relocation could be overturned. Hardly surprising when no formal agreement has been reached. The person at Art Front Gallery however didn’t seem to feel revoking the work’s removal was a viable option. This despite the fact that no “consensus” has been reached. Art Front Gallery has consistently taken the attitude that there will be no backtracking on Mount Ida‘s removal unless the owner decides to do so, and told me on the phone that “we are only observers” and “our position is neutral.” (Neutral? Aren’t you the lot who did the art planning?) AFG’s strong assertion of Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C.’s ownership rights, while saying nothing in particular about copyright, did not sit well with me either. It seems to have taken my intervention (?) for them to even notice the difference between their perception of the matter, and that of the artist, and one couldn’t help feeling that artist and art planners were not exactly in lockstep here.

Okazaki’s sculpture was conceived as an area of plantings or garden inaccessible to humans, but accessible to birds, cats, insects etc. (plants were specifically chosen that birds would peck at). The branches of trees covered in summer foliage protrude from the fence, altering the strangely twisted and severed form created by the artist. Inadvertently invalidating the cut-surface shapes as if soothing a wound, the trees are a lovely sight. But that sight will no longer be seen. (Will the plants be “relocated” as well? Will the animals just be abandoned?) Okazaki said Mount Ida was for animals, but it has plenty for humans too. Whether for relaxing, eating lunch, napping in the sun, or as a rendezvous point, people really love this place, and surely it is the perfect fit for a “(provisionally-titled) Place du Marché.” There could be no “warmer” place from a commercial viewpoint either. Just leave it alone.

——————————–

*1 I emailed the artist on October 15, then as written here, called him, subsequently emailing back and forth several times, and speaking on the phone once more. On October 18 I sent four questions to Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C. via their online inquiry form, and on the 20th received a reply from Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C. owner/operator Toshin Development Co., Ltd. Basically the same questions were sent on the same day, the 18th, to Art Front Gallery through their website, then on the 21st I received a call from a member of staff who generously spoke with me for over an hour. “On the removal of Okazaki Kenjiro’s work from Faret Tachikawa” is based on these conversations. Allow me here to thank those who took the time to talk with me.

*2 According to the website the official title is “FARET Tachikawa Art,” but it is also often referred to as the Faret Tachikawa Art Project. Most generally though, it is known simply as “Faret Tachikawa.” The author has written about Faret Tachikawa previously, including in the REALKYOTO blog that preceded this column, ie “Faret Tachikawa turns 21”.

*3 In his book Faret Tachikawa Public Art Project: Art Transforms a Base Town (Gendai Kikakushitsu, 2017) Kitagawa Fram notes that when it comes to the remodeling or demolition of buildings in the complex, in order to avoid unilateral decisions by the owner around the preservation or removal of any artworks installed on the site, “such decisions are made through discussions between the owner, artist and planners” (in this case Tachikawa Takashimaya S.C. and Okazaki Kenjiro and Kitagawa Fram/Art Front Gallery/the Faret Tachikawa Art management committee). Kitagawa’s book takes a fascinating, in-depth look at the origins of Faret Tachikawa, including the financial aspects of the project. Its embattled art planner, Kitagawa, in his late 40s at the time, was exploring how to inject fresh ideas, and a totally new concept, into the hidebound field of public art. This book gives an insight into some of his ideas, and is essential reading for any aspiring curator. I think this would be a good opportunity for Kitagawa himself to reacquaint himself with its contents.

——————————–

Fukunaga Shin

Novelist