Cultural Currency 6: Kim Sajik “From the ‘Story’ series: Vessel is Walk on the Mountain” @ PURPLE

Being a concerned party

By Shimizu Minoru

2022.12.09

The June 1974 issue of the quarterly magazine Shashin hihyo [Photo review] was titled Tokushu: ‘kiroku’ wo megutte (Special edition: On “recording”) and featured a trialogue, “Rekishi=nichijo” (History=the everyday), involving Araki Nobuyoshi, Takanashi Yutaka and Kuwabara Shisei with Shigemori Koen as moderator. In it, a young and sharp Araki commented as follows:

“Story” was divided from the outset. On the one hand, because the artist is a Zainichi Korean and Korean customs and manners appear in much of her work, one would assume she is expressing her identity as a member of a so-called “minority.” On the other hand, motifs and forms from famous paintings and religious images unrelated to Korea—Jan van Eyck, triptychs, peaches from the Kojiki, rice ears from Shinto, Imperial Japanese Army bayonets, Peruvian mummies, etc.—are mixed in, and this identity becomes hybridized. In the post-colonial era, unless one is extremely ignorant of history or naïve, it is surely impossible to believe in such essential concepts as unitary ethnic groups, races or nations, myths and traditions, masculinity and femininity, and so one assumes the artist is standing on the side of non-essentiality, plurality and hybridity. But in her artist statements, outdated views of men and women of the kind that would give feminists goosebumps appear, such as, “I think that whereas men were looking for ways of connecting with society, women were continually looking for ways that lifeforces could connect,” and the essential dualisms I mentioned above remain.

“Story” was divided from the outset. On the one hand, because the artist is a Zainichi Korean and Korean customs and manners appear in much of her work, one would assume she is expressing her identity as a member of a so-called “minority.” On the other hand, motifs and forms from famous paintings and religious images unrelated to Korea—Jan van Eyck, triptychs, peaches from the Kojiki, rice ears from Shinto, Imperial Japanese Army bayonets, Peruvian mummies, etc.—are mixed in, and this identity becomes hybridized. In the post-colonial era, unless one is extremely ignorant of history or naïve, it is surely impossible to believe in such essential concepts as unitary ethnic groups, races or nations, myths and traditions, masculinity and femininity, and so one assumes the artist is standing on the side of non-essentiality, plurality and hybridity. But in her artist statements, outdated views of men and women of the kind that would give feminists goosebumps appear, such as, “I think that whereas men were looking for ways of connecting with society, women were continually looking for ways that lifeforces could connect,” and the essential dualisms I mentioned above remain.

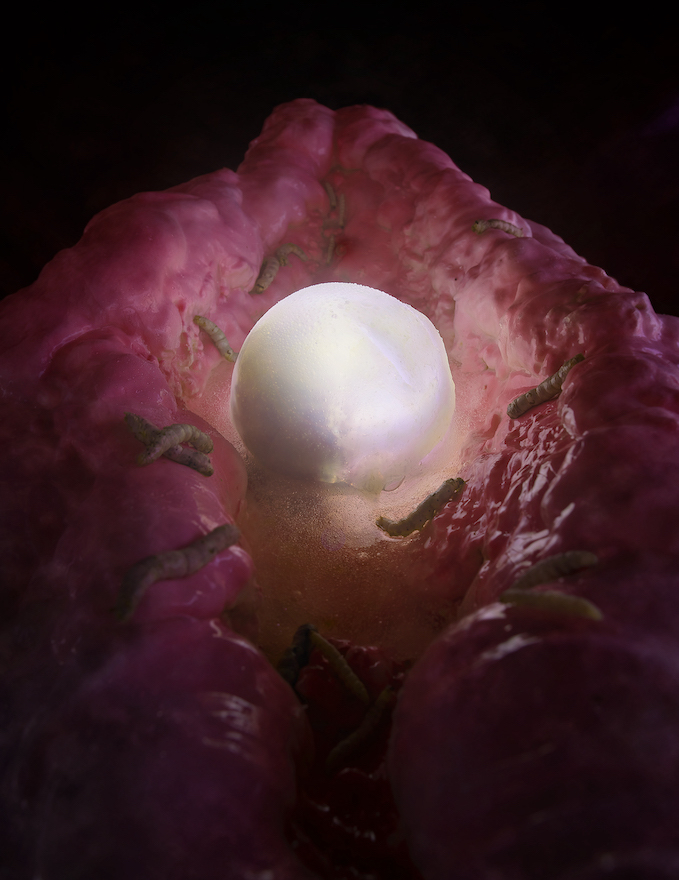

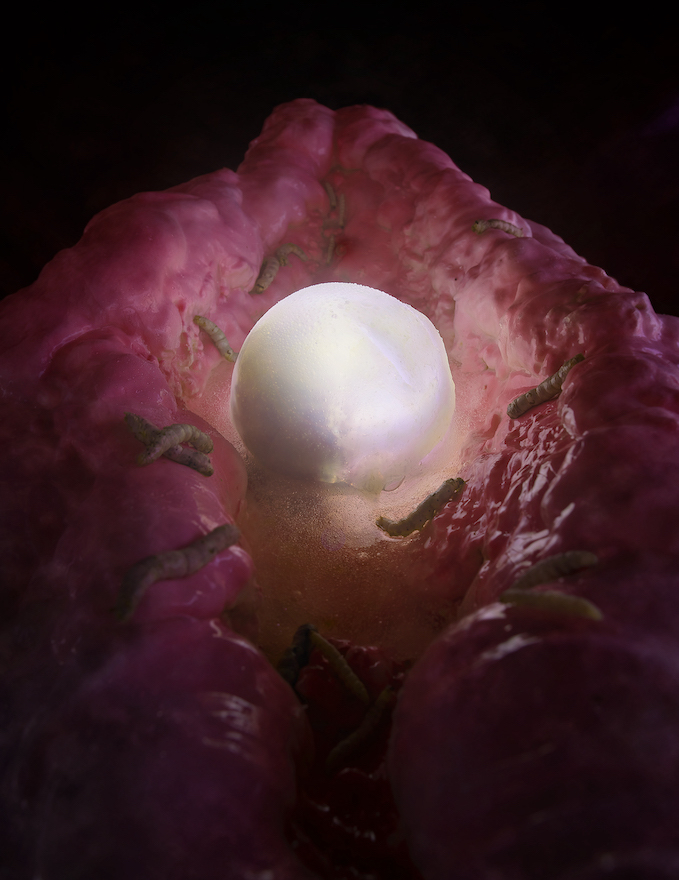

People who have viewed the entire series will no doubt realize that the theme of this book is none other than this “division.” Fallen from an androgynous utopia, a hen, Creator of the world, has its head chopped off and spouts flowers instead of blood. A pair of twins (one dressed in blue, the other in red) inhabit this place, at which point a story (history) divided in two begins. The twins grow up while wavering between such poles as life (pregnancy, birth, growth) and death (infertility, destruction, aging), male and female, stillness and movement, peace and violence, and nature and artifice, until a climax is reached in the central panel of a triptych watched over by two Asiatic black bears dressed in blue and red in which, as if referencing the history of photography, an image of the Virgin Mary (dressed in blue) clutching the dead body of Jesus Christ (dressed in red) appears. This image of the two figures witnessing the birth of a new life (a fertile egg) between the world of the Sun and the world of the Moon is reflected on the surface of a lake, where it is transformed into a Pietà with the figure in red holding the figure in blue.

People who have viewed the entire series will no doubt realize that the theme of this book is none other than this “division.” Fallen from an androgynous utopia, a hen, Creator of the world, has its head chopped off and spouts flowers instead of blood. A pair of twins (one dressed in blue, the other in red) inhabit this place, at which point a story (history) divided in two begins. The twins grow up while wavering between such poles as life (pregnancy, birth, growth) and death (infertility, destruction, aging), male and female, stillness and movement, peace and violence, and nature and artifice, until a climax is reached in the central panel of a triptych watched over by two Asiatic black bears dressed in blue and red in which, as if referencing the history of photography, an image of the Virgin Mary (dressed in blue) clutching the dead body of Jesus Christ (dressed in red) appears. This image of the two figures witnessing the birth of a new life (a fertile egg) between the world of the Sun and the world of the Moon is reflected on the surface of a lake, where it is transformed into a Pietà with the figure in red holding the figure in blue.

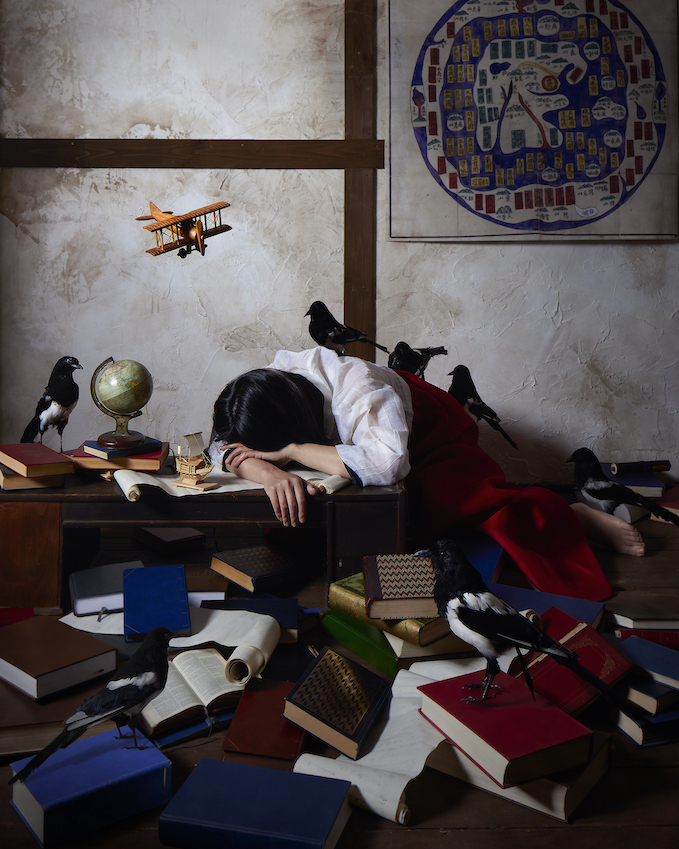

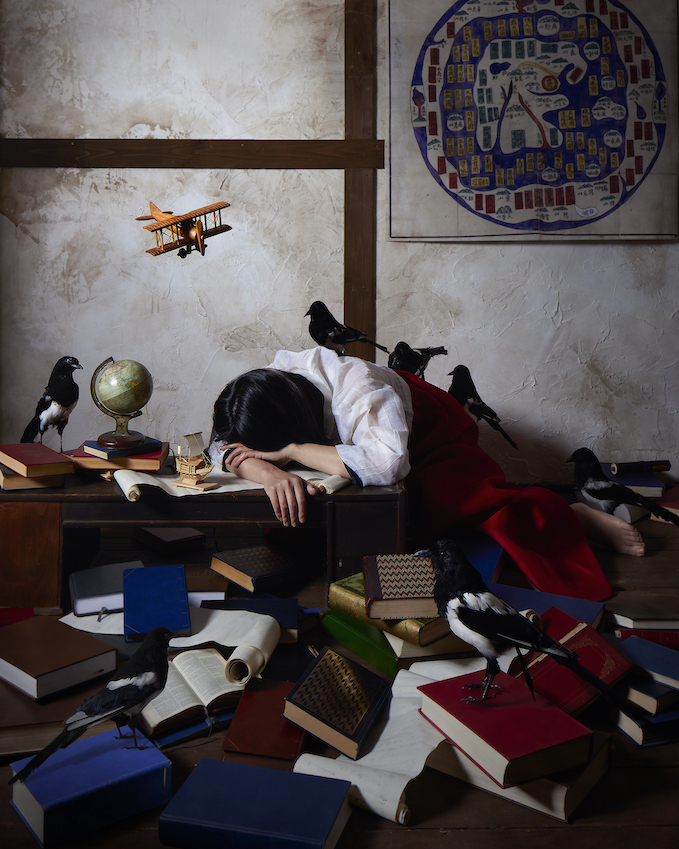

Throughout the series, the locations, textures of the clothing, skin and geological formations, materials and models have been carefully selected and the viewer never tires of looking at them. In particular, it seems time was taken to seek out elderly, male and child models, including obese giants, men with heavy jaws and arms, and a taciturn, absentminded-looking child Showa era in air. At the same time, in retrospect, Kim’s presentation is rather kitsch, lending the serious theme of the division experienced by those subject to discrimination a peculiar lightness. Some people will also no doubt find it difficult to control the urge to laugh at the undisguised stuffed specimen-like appearance of the Asiatic black bears.

Throughout the series, the locations, textures of the clothing, skin and geological formations, materials and models have been carefully selected and the viewer never tires of looking at them. In particular, it seems time was taken to seek out elderly, male and child models, including obese giants, men with heavy jaws and arms, and a taciturn, absentminded-looking child Showa era in air. At the same time, in retrospect, Kim’s presentation is rather kitsch, lending the serious theme of the division experienced by those subject to discrimination a peculiar lightness. Some people will also no doubt find it difficult to control the urge to laugh at the undisguised stuffed specimen-like appearance of the Asiatic black bears.

Kim approaches the difficult task of expressing the absurdity of this world as a concerned party in the position of a member of a minority not through “reality as it is” but through “story.” Because being a concerned party is to be forced into duality, neither singular nor plural, to be seized by and torn to pieces by dualisms. “Story” is local. It does not transcend Japan and Zainichi, male and female. The barrier of identity stands in the way. Kim knows this full well. But plurality! The identities of multiple individuals! Post-colonial non-essentialism! An identity-free, diverse society!… Confronted with such ideal, conceptual correctness to which everyone nods their head, the minds of concerned parties fill with rancor. This book is the sublimation of this rancor.

Kim approaches the difficult task of expressing the absurdity of this world as a concerned party in the position of a member of a minority not through “reality as it is” but through “story.” Because being a concerned party is to be forced into duality, neither singular nor plural, to be seized by and torn to pieces by dualisms. “Story” is local. It does not transcend Japan and Zainichi, male and female. The barrier of identity stands in the way. Kim knows this full well. But plurality! The identities of multiple individuals! Post-colonial non-essentialism! An identity-free, diverse society!… Confronted with such ideal, conceptual correctness to which everyone nods their head, the minds of concerned parties fill with rancor. This book is the sublimation of this rancor.

——————————–

1. Shashin hihyo [Photo review] 6 (1974): 46.

2. Ishikawa Takeshi, Minamata Note 1971–2012: Watashi to Yūjin Sumisu to Minamata [Me and Eugene Smith and Minamata] (Tokyo: Chikura, 2012), 137, 139–40. “Tomoko has endured and put up with so much while continually being exposed to television lighting and camera flashes.” “We don’t want to force her to endure this until she dies.” That the copyright holder, Aileen M. Smith, agreed to the withdrawal of the “Minamata Pietà” from further publication demonstrates that the relationship between the Smiths and Minamata was by no means a “lie” or a “charade.”

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University.

Kim Sajik “From the ‘Story’ series: Vessel is Walk on the Mountain” was held at PURPLE, October 27 through November 14, 2022.

Pre-order Kim Sajik’s Story from the PURPLE website.

The advertising system and the photography system are extremely close, much more so than has been the case with news photography till now. Put in extreme terms, so close they may as well be treated as equals. … Which is why I really like advertising. Magazine advertising pages seem so much realer that photo features. Because they come at you with a bang. That’s why advertising seems real, whereas Minamata is a lie. People will get angry at me for saying it’s a lie, but it’s a charade; advertising is realer.1

The photo Araki rejects as a “lie” and a “charade” is perhaps the most famous in the series contained in W. Eugene Smith’s Minamata: Life—Sacred and Profane (1973, Sohjusha), published the year before this trialogue took place. Known as the “Minamata Pietà,” it depicts the Minamata disease sufferer Kamimura Tomoko and her mother in the bath. Cradled by her mother and showing the symptoms characteristic of Minamata disease, Tomoko’s body and limbs form a sharp contrast with the loving gaze directed at them, the image at once assaulting the viewer and inevitably calling to mind images of the Virgin Mary holding the dead body of her son, Jesus Christ. What viewer would not weep at this “charade”? According to Minamata Note 1971-2012 by Ishikawa Takeshi, who worked as Smith’s assistant, the photographer himself was conscious of the fact that his own “Minamata” was a “failure.” Similarly, the family of Tomoko, who died several years later, grew uncomfortable as a result of the image of their daughter becoming an icon of Minamata disease and ultimately withdrew the photograph from further publication (1998). They did so because they believed the photo no longer showed the anguish or reality of the parties concerned, and regardless of the subjects (including the parties concerned), it would end up being used as catharsis—a heart-rending charade or piece of misery pornography.2

*

Kim Sajik gained attention in 2016 as the winner of the Grand Prize in Canon’s New Cosmos of Photography competition. Her winning entry, “Story,” consisted of a series of so-called “staged photos” in which the artist skillfully combined motifs borrowed from myths and legends from around the world with such conceptual pairings as life and death, male and female, natural and manmade and state (nation, majority) and ethnic group (Zainichi Korean, minority) to create a hybrid “story.” Once completed, the series will be published as a photobook by AKAAKA (due out in December 2022).

Sōtō no hakuja

Ken ni tsuchi

Futago

Jimen o kiriwakeru

Tamago ga shutsugensuru

Eien ni aruku hitobito

Yume ni miru musume (7 hiki no tori to)

——————————–

1. Shashin hihyo [Photo review] 6 (1974): 46.

2. Ishikawa Takeshi, Minamata Note 1971–2012: Watashi to Yūjin Sumisu to Minamata [Me and Eugene Smith and Minamata] (Tokyo: Chikura, 2012), 137, 139–40. “Tomoko has endured and put up with so much while continually being exposed to television lighting and camera flashes.” “We don’t want to force her to endure this until she dies.” That the copyright holder, Aileen M. Smith, agreed to the withdrawal of the “Minamata Pietà” from further publication demonstrates that the relationship between the Smiths and Minamata was by no means a “lie” or a “charade.”

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University.

Kim Sajik “From the ‘Story’ series: Vessel is Walk on the Mountain” was held at PURPLE, October 27 through November 14, 2022.

Pre-order Kim Sajik’s Story from the PURPLE website.