Cultural Currency 17: Mugyuda Hyogo "Iroseki Sorasaki Ikikaekakaka" @ Kyoto Art Center

At the end of a steady gaze, the photography of Mugyuda Hyogo

By Shimizu Minoru

2023.10.26

Mugyuda Hyogo resembles a pianist who has perfect technique but cannot rid himself of peculiar habits. Like a musician who can produce great songs from even the most mediocre humming, this photographer turns anybody, any ruins or trash, beautiful and strange-looking alike, he finds along the Keihan and Gakkentoshi lines, which is to say the rustic suburbs of Osaka and Nara, into fascinating photographs. A skilled technician, Mugyuda is also a genius who makes people let down their guard, getting a man he met ten minutes ago to leap naked into a pond and ten minutes later entering the home of a stranger to shoot photos.

While continuing to upload photos daily to his blog, “pile of photographys,” an activity reminiscent of On Kawara’s “Today” series, Mugyuda has also devoted himself to producing work under the title “Artificial S.” Though it seems to have no direct connection to this exhibition, the S in Artificial S could conceivably stand for “subjectivity/subject” (the photographer’s intent / the thing being photographed, i.e., the theme), or the impersonal pronoun es (German for “it”). In other words, it stands for the subjectivity of a photo, the theme of a photo, and the focus of the impersonal camera eye, with a single photograph arising from the interaction between these three artificial constructions. Photography is a place where, by means of a constructed impersonality, constructed subjectivity and constructed subject are united as “pairs,” and Mugyuda’s exhibitions continually seek this place as if staring fixedly at it. Gocho Shigeo was another artist who lived photography as “pairs” at a place removed from so-called konpora shashin (contemporary photography),1 but if Gocho’s “pairs” were always a symmetrical (facing) self and other, or self and the world, in the sense that symmetry is not guaranteed due to the presence of a third item in the form of the camera, Mugyuda’s pairs are asymmetrical.

This exhibition was staged across two venues: the South Gallery and the North Gallery at the Kyoto Art Center. At first glance, the South Gallery appeared to contain a collection of familiar, routine snapshots, but upon closer inspection it became clear that it contained images that only existed as photos (water surfaces and waterdrops captured using high-resolution/high-speed photography making them look as if they had stopped while glistening in midair, images of still objects whose highlights were accentuated through the use of longish exposure, etc.) and images on the theme of photography (various kinds of backlighting, pluramonity, single eyes, blindness) presented as actual objects in the form of printed sheets of paper suspended just in front of the walls. As if to say these fragments of a familiar world are in fact non-existent digital images, and that what we are actually seeing now is just paper. However, while the exposed lengths of wood from which the photos were suspended may have been used to add a not overly elaborate casualness to the exhibition, this staged casualness in fact seemed unnatural. The installation emulated the approach adopted by Wolfgang Tillmans of displaying photos of various sizes together on the same wall and also had similar themes – a game in which several people crowd together to form a single mass [see Knotenmutter (1994)] – but I do not think it was successful. All the more because each of the selected photos possessed sufficient intensity, it probably would have been better to omit the excessive (immature?) installation.2

This exhibition was staged across two venues: the South Gallery and the North Gallery at the Kyoto Art Center. At first glance, the South Gallery appeared to contain a collection of familiar, routine snapshots, but upon closer inspection it became clear that it contained images that only existed as photos (water surfaces and waterdrops captured using high-resolution/high-speed photography making them look as if they had stopped while glistening in midair, images of still objects whose highlights were accentuated through the use of longish exposure, etc.) and images on the theme of photography (various kinds of backlighting, pluramonity, single eyes, blindness) presented as actual objects in the form of printed sheets of paper suspended just in front of the walls. As if to say these fragments of a familiar world are in fact non-existent digital images, and that what we are actually seeing now is just paper. However, while the exposed lengths of wood from which the photos were suspended may have been used to add a not overly elaborate casualness to the exhibition, this staged casualness in fact seemed unnatural. The installation emulated the approach adopted by Wolfgang Tillmans of displaying photos of various sizes together on the same wall and also had similar themes – a game in which several people crowd together to form a single mass [see Knotenmutter (1994)] – but I do not think it was successful. All the more because each of the selected photos possessed sufficient intensity, it probably would have been better to omit the excessive (immature?) installation.2

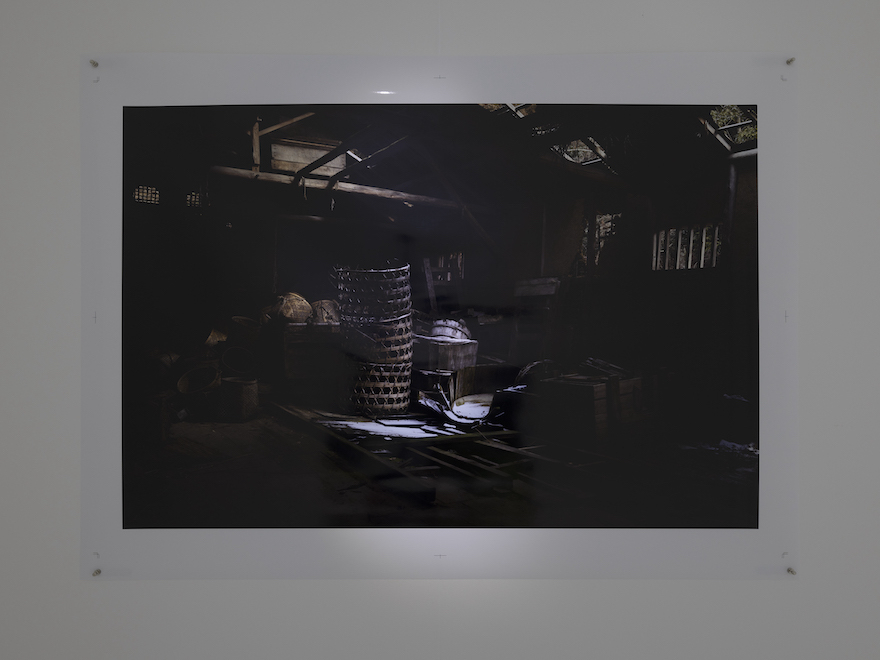

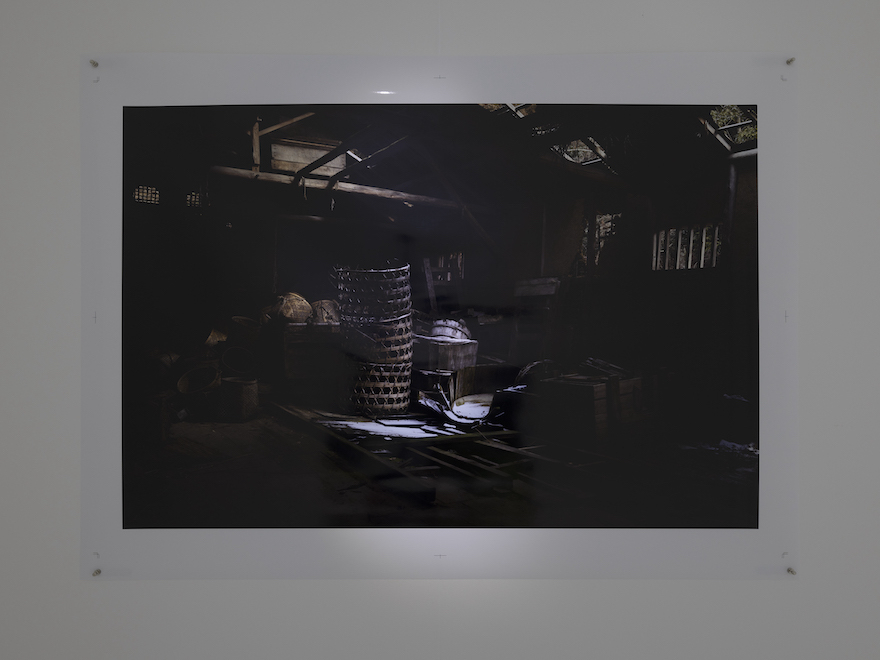

In contrast to this, the installation in the North Gallery was highly effective, making viewers return to look at the works again and again and leaving a deep impression. The theme was methods of receiving the visual information contained in photos as reality and experiments in moving images a step closer to reality. The foundation of this installation was lighting, and in what could be called a simple solution that seems obvious in retrospect, the artist simply arranged the lighting to match with the light in the photos.3 Specifically, he illuminated slightly the bright parts of photos (droplets of light like those in the paintings of Vermeer, highlights, celestial bodies) by training spotlights on these parts, and trained light whose source was hidden in the direction from which light shone in the photos (a bright sky, for example). In the former cases where the size of the works was large, it was almost as if one was encountering actual scenes, and only when one blocked the light from the spotlights with one’s hand did the works turn back into photos. In the latter cases where the size of the works was relatively small, real light shone from deserted houses in the suburbs or cloudless white skies, making it seem as if one were peering into some distant world.

In contrast to this, the installation in the North Gallery was highly effective, making viewers return to look at the works again and again and leaving a deep impression. The theme was methods of receiving the visual information contained in photos as reality and experiments in moving images a step closer to reality. The foundation of this installation was lighting, and in what could be called a simple solution that seems obvious in retrospect, the artist simply arranged the lighting to match with the light in the photos.3 Specifically, he illuminated slightly the bright parts of photos (droplets of light like those in the paintings of Vermeer, highlights, celestial bodies) by training spotlights on these parts, and trained light whose source was hidden in the direction from which light shone in the photos (a bright sky, for example). In the former cases where the size of the works was large, it was almost as if one was encountering actual scenes, and only when one blocked the light from the spotlights with one’s hand did the works turn back into photos. In the latter cases where the size of the works was relatively small, real light shone from deserted houses in the suburbs or cloudless white skies, making it seem as if one were peering into some distant world.

Contrariwise to these trompe l’oeil-like works, with the photo of an abandoned crematory, the training of a spotlight on the hearth (which in normal conditions would be too dark to see) enabled viewers to see the grubby interior. Witnessing details that were previously invisible emerge when real light is shone on dark areas of photos is a peculiar experience. Because here, it is not that “things that were invisible are being made visible through photography,” but that the photos themselves are taking on invisibility and turning into things in which “one cannot see everything,” or in other words into reality.

Contrariwise to these trompe l’oeil-like works, with the photo of an abandoned crematory, the training of a spotlight on the hearth (which in normal conditions would be too dark to see) enabled viewers to see the grubby interior. Witnessing details that were previously invisible emerge when real light is shone on dark areas of photos is a peculiar experience. Because here, it is not that “things that were invisible are being made visible through photography,” but that the photos themselves are taking on invisibility and turning into things in which “one cannot see everything,” or in other words into reality.

Finally, a word about the grotesque subjects that appear without exception in Mugyuda’s exhibitions. In this show, examples include a crushed worm, the dead body of a young bird and an abandoned masturbator (fellatio specifications). These are what one might call abject motifs, but in the same way that the glistening waterdrops, cute children, flowers and insects are photogenic, these abject subjects are also photogenic. Perhaps Mugyuda is counterbalancing images of the bright surface of society and those of its dark underbelly. But this is simply combining plus and minus to create zero. A predilection for the abject is the same as an inclination towards photography zero degree, in which case, transformed into harmlessness, the abject is perhaps crying.

Finally, a word about the grotesque subjects that appear without exception in Mugyuda’s exhibitions. In this show, examples include a crushed worm, the dead body of a young bird and an abandoned masturbator (fellatio specifications). These are what one might call abject motifs, but in the same way that the glistening waterdrops, cute children, flowers and insects are photogenic, these abject subjects are also photogenic. Perhaps Mugyuda is counterbalancing images of the bright surface of society and those of its dark underbelly. But this is simply combining plus and minus to create zero. A predilection for the abject is the same as an inclination towards photography zero degree, in which case, transformed into harmlessness, the abject is perhaps crying.

——————————–

1. See Shimizu Minoru, “Provoke and Konpora,” in On Digital Photography (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 2020). 2. Additionally, the contemporary poetry-like exhibition title (holding back color giving rise to emptiness and splitting emptiness giving rise to color are in the realm of the Buddhist concept of “form is emptiness,” in which all language comes to life and regains the immediacy of onomatopoeia…?) also fails to impress. Assuming this is accurate, onomatopoeic words are pure forms of differentiated phonemes that lack referents, and are in fact awkward words that are difficult to translate. With a limited basic lexicon, Japanese relies heavily on onomatopoeia (often formed by repeating a word, such as gorigori [scraping] and mozomozo [squirming]), and Japanese native speakers not only understand these intuitively but also coin their own versions (e.g., mofumofu [fluffy]), which is a never-ending problem for Japanese language learners. 3. In addition to the works using lighting, there were also works in which photos of children presenting small animals (crab, frog, tortoise) in the direction of the viewer were displayed in such a way that they were literally pushed this way, and a work in which a round photo was reflected in a mirror. The effect of the latter was uncanny, with the image squared giving rise to a peculiar sense of reality, as if the minus was squared and turned into a plus. This was all the more so because the subject was a grotesque “mouth.”

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University.

FOCUS#5 Mugyuda Hyogo “Iroseki Sorasaki Ikikaekakaka” was held at Kyoto Art Center from August 19 to September 18, 2023.

——————————–

1. See Shimizu Minoru, “Provoke and Konpora,” in On Digital Photography (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 2020). 2. Additionally, the contemporary poetry-like exhibition title (holding back color giving rise to emptiness and splitting emptiness giving rise to color are in the realm of the Buddhist concept of “form is emptiness,” in which all language comes to life and regains the immediacy of onomatopoeia…?) also fails to impress. Assuming this is accurate, onomatopoeic words are pure forms of differentiated phonemes that lack referents, and are in fact awkward words that are difficult to translate. With a limited basic lexicon, Japanese relies heavily on onomatopoeia (often formed by repeating a word, such as gorigori [scraping] and mozomozo [squirming]), and Japanese native speakers not only understand these intuitively but also coin their own versions (e.g., mofumofu [fluffy]), which is a never-ending problem for Japanese language learners. 3. In addition to the works using lighting, there were also works in which photos of children presenting small animals (crab, frog, tortoise) in the direction of the viewer were displayed in such a way that they were literally pushed this way, and a work in which a round photo was reflected in a mirror. The effect of the latter was uncanny, with the image squared giving rise to a peculiar sense of reality, as if the minus was squared and turned into a plus. This was all the more so because the subject was a grotesque “mouth.”

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University.

FOCUS#5 Mugyuda Hyogo “Iroseki Sorasaki Ikikaekakaka” was held at Kyoto Art Center from August 19 to September 18, 2023.