According to Hashimoto Osamu, Japanese painting reached a “turning point” with Maruyama Okyo’s

shasei (realistic depiction achieved by closely examining and understanding the subject).

1 Until then, painting (ink wash painting) consisted of 画

ga (images) of the spiritual world. Being images of a world invisible to begin with, there was no shortage of styles that were ostensibly strange. Strange as they may have seemed to the worldly eye, to the spiritual eye these were what constituted “painted images.” Even if something incomprehensible was depicted, if a high-ranking priest or man of culture and understanding said “It’s a landscape,” then it was a real landscape. Before long, strange lines created in the belief that they had superior spiritual qualities also became established as a new technique. The history of ink wash painting is also a process whereby innovative expression arising from spirituality has become secularized as mere technique. In other words, painting was a competition between invisible spirituality and visible technique.

With

shasei, however, spirituality was abandoned and 絵図

ezu (picture) rendered autonomous. Only subject and technical skill were present, and when Okyo used the

tsuketate technique, reliant on outline-free single brushstrokes, to seamlessly conjoin wisteria vines and abstract curved lines (

Wisteria, 1776, Nezu Museum), painting was transformed into a balance between representation and brushwork. As is commonly known, Soga Shohaku criticized Okyo’s

ezu, which exhibited brilliant technique alone and were devoid of philosophical content.

But what exactly is

shasei? In 18th-century Kyoto, which was saturated with various techniques and aesthetics such as Kano school, Yamato-e, Rimpa school, Nanga school, and Chinese “literati painting,” Okyo’s

shasei crystalized with

megane-e (paintings designed to be viewed through an optical device that heightens the illusion of depth created using Western perspective), Chinese printed books, and Shen Nanpin as catalysts. It was based on three negations. Firstly, Chinese poetic culture or philosophical meaning would not be prioritized in painting. In other words, paintings are meant to be “viewed,” not “read.” Secondly, homogenous, empty perspectival space would not be employed. At this point, one of the essences of Western painting is already intentionally excluded. Finally,

shasei is not

shakei, or realistic representation in which the subject is simply depicted as it is. Accordingly, the dualism of either rough brushwork or detailed depiction is nonexistent.

In short,

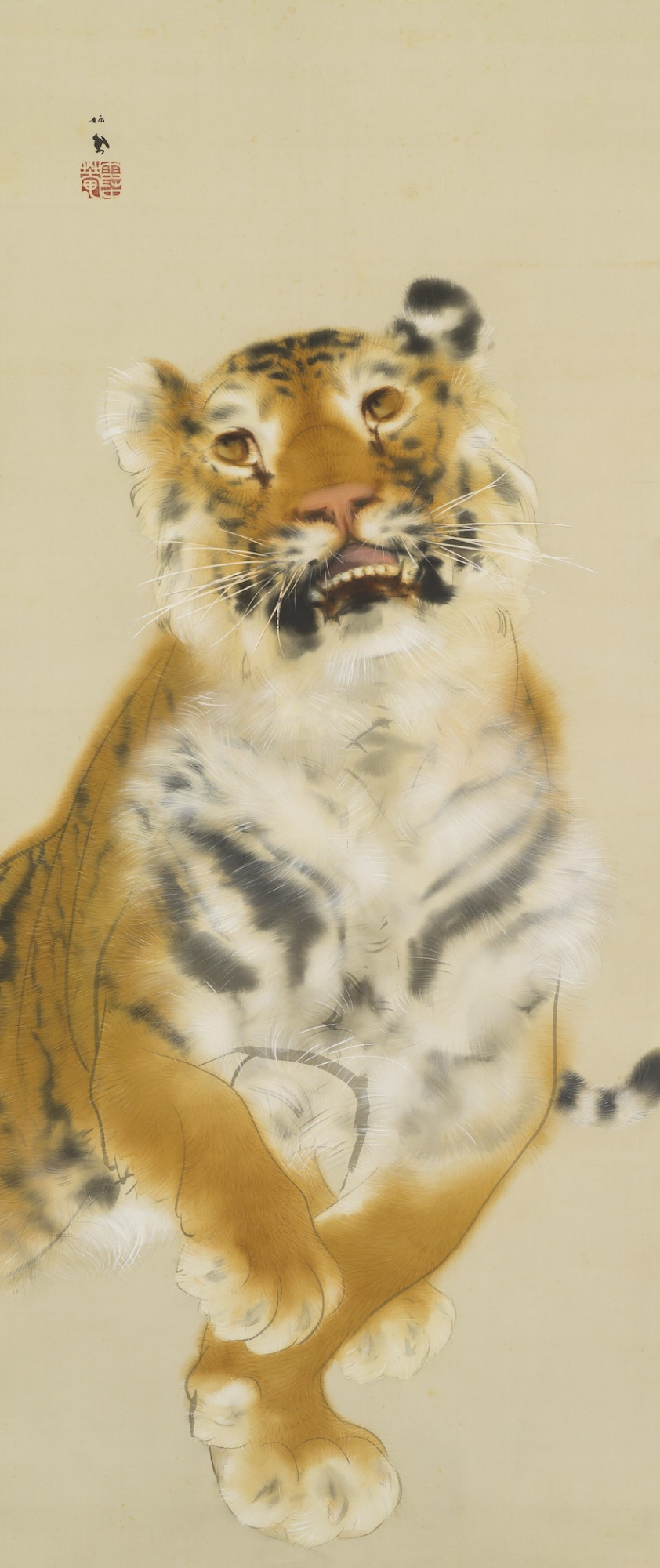

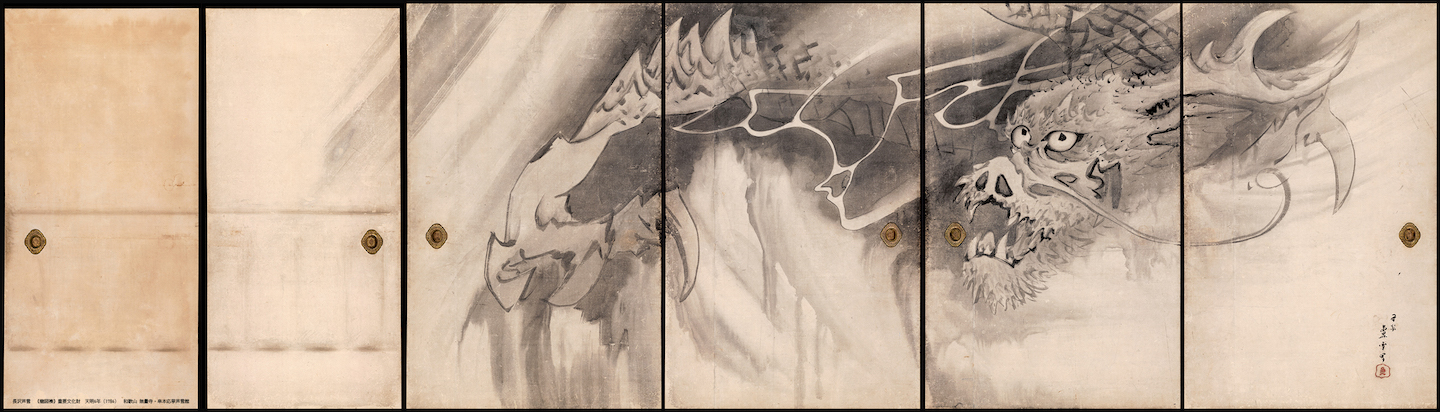

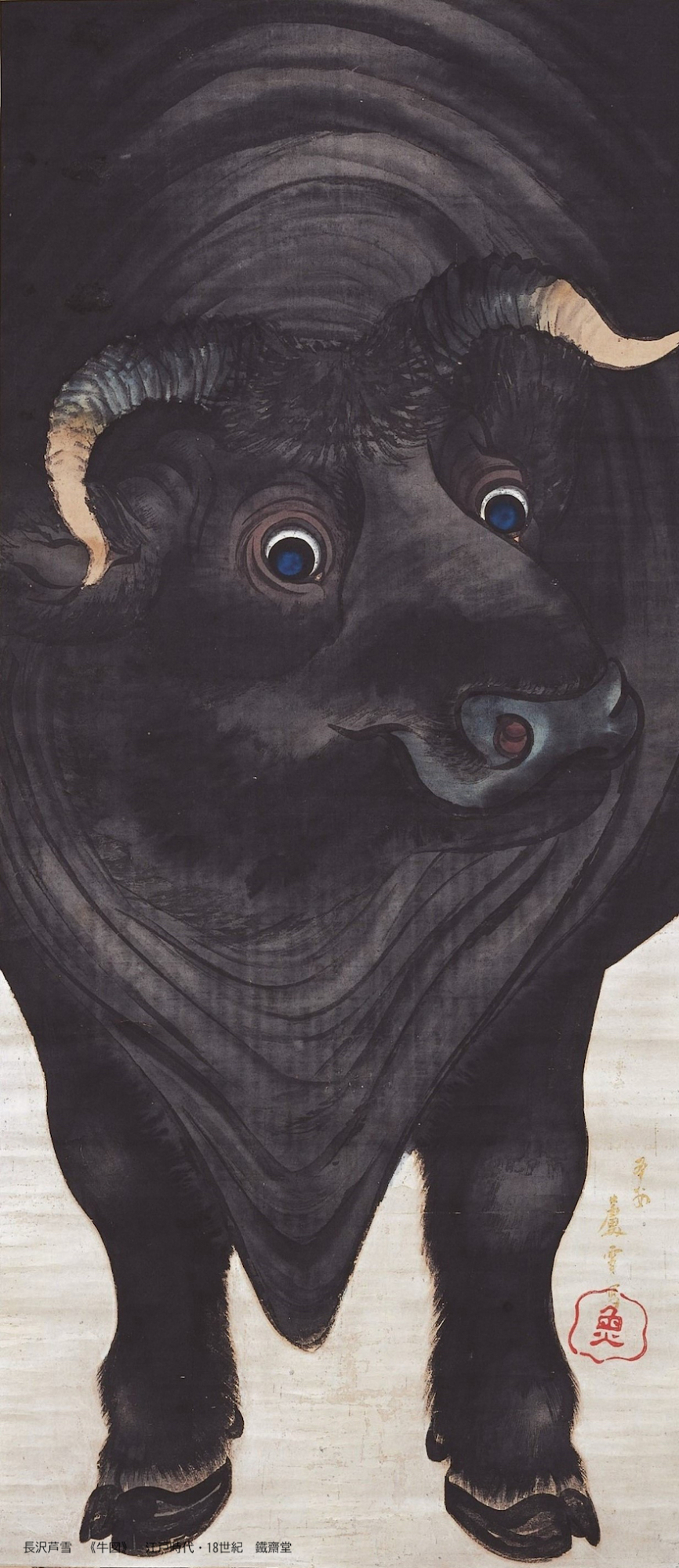

shasei is what a manga artist does when they become used to drawing their own manga characters and are able to give life as characters to flowers, birds, tigers and dragons, as if varying and using their own characters at will (sometimes precisely, sometimes roughly). When a tiger is not placed in a pre-constructed empty space, but “vividly animated” as a character, painterly space forms around it.

Shasei paintings are collages of various spaces generated by characters that have been mastered in this way. It is from here that the essential importance of frame, blank space, and the earth (the horizon, or a suggestion that it exists if it is not actually depicted) arises. Nagasawa Rosetsu is known as Maruyama Okyo’s “mold-breaking” pupil, but the “mold” Rosetsu broke was this

shasei.

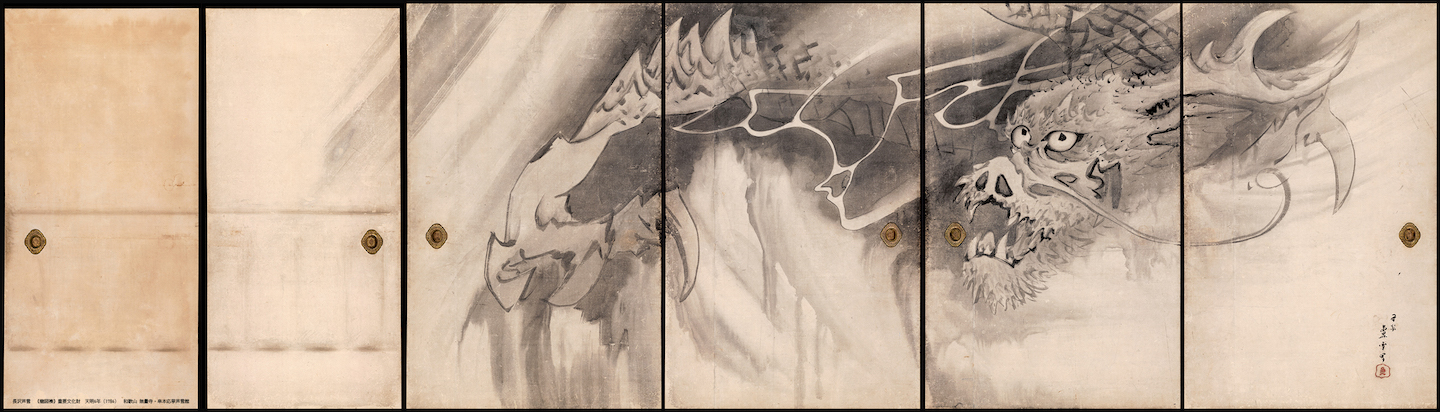

Nagasawa Rosetsu, Dragon, 1786, Kushimoto Okyo Rosetsu Art Museum at Muryoji Temple, Wakayama

(on view through November 5)

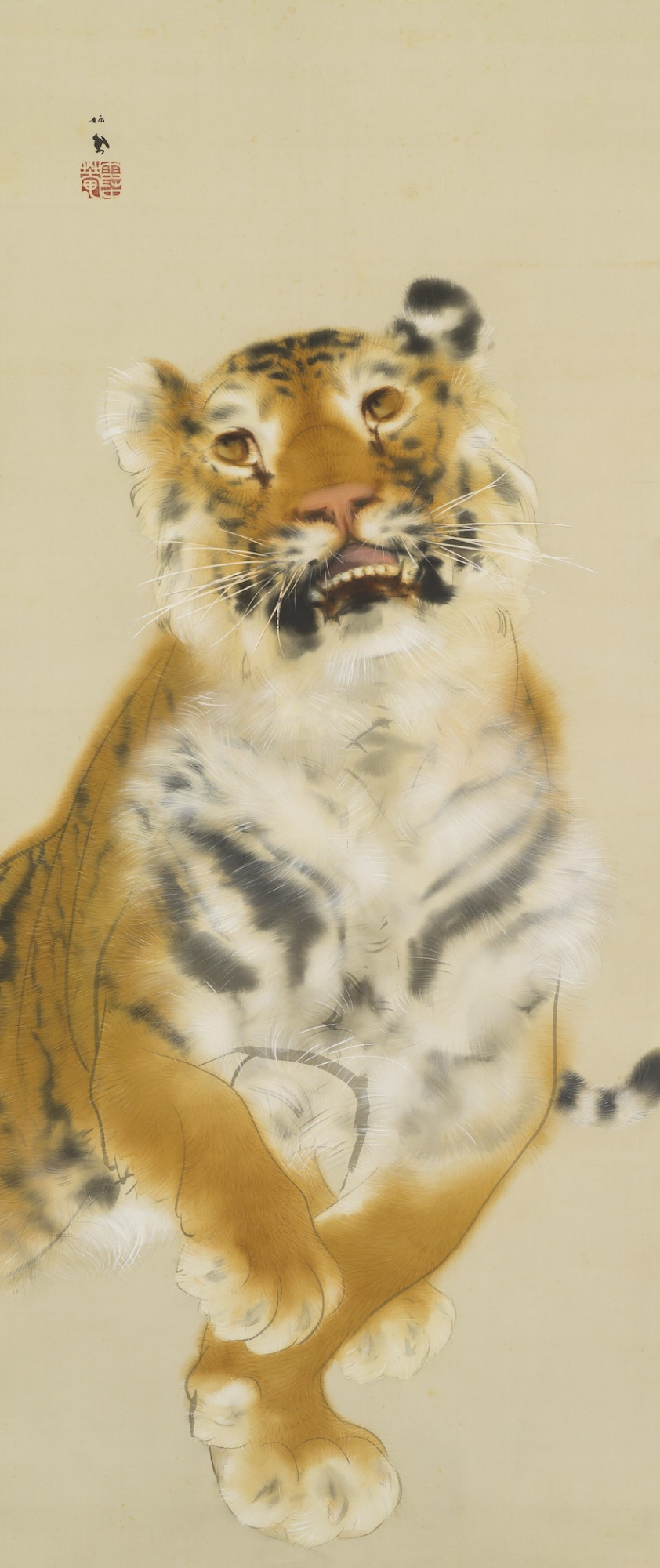

Nagasawa Rosetsu, Tiger, before 1786, Kushimoto Okyo Rosetsu Art Museum at Muryoji Temple, Wakayama

(on view through November 5)

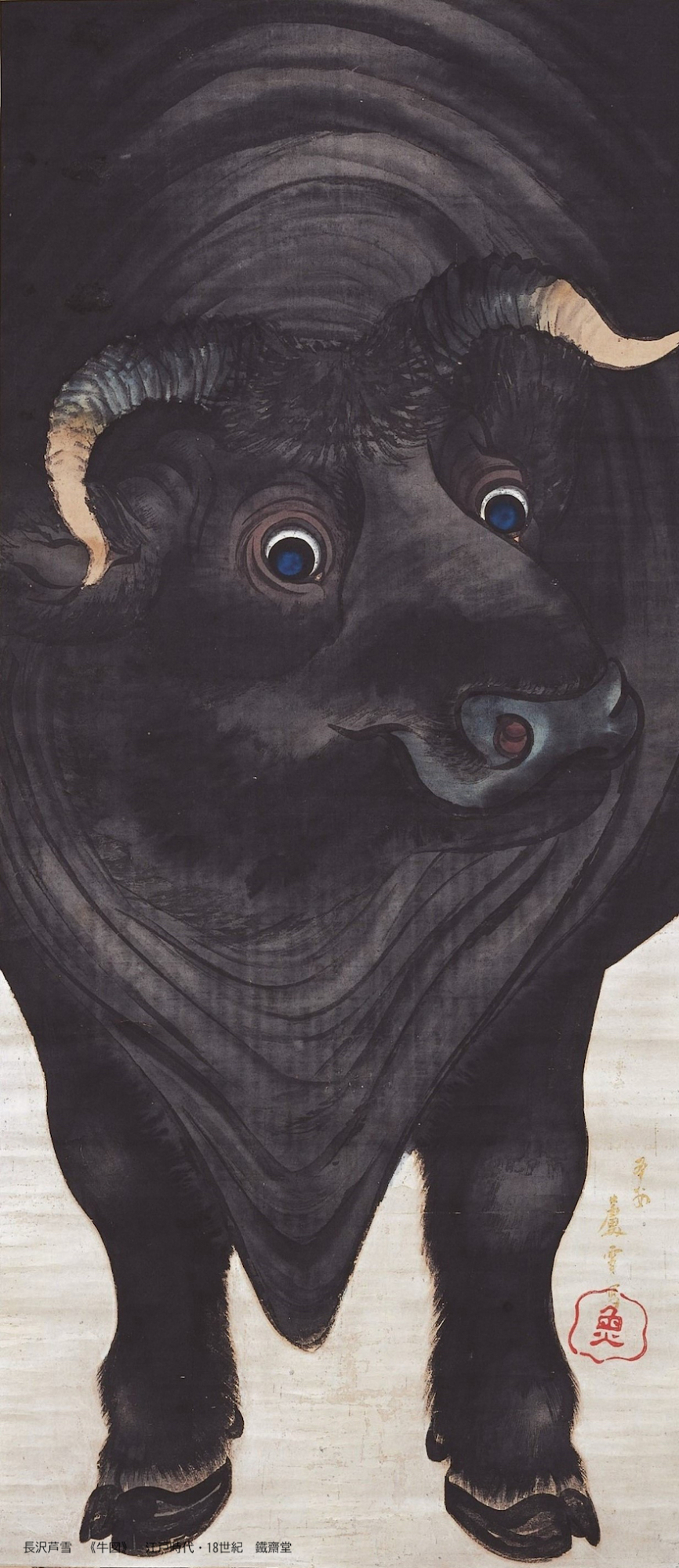

Nagasawa Rosetsu, Cow, early Kansei period (1789–99), Tessaido

I stated above that “painting became a balance between representation and brushwork,” but this balance is maintained by the following sequential order: the artist becomes used to painting a certain representation → this representation is “characterized” as a balance between representation and brushwork → multiple characters are painted → multiple spaces are generated → the earth as a balance between these spaces → blank space is added to these spaces based on the earth → the picture plane reaches the outer frame → the picture plane naturally becomes a painting. Because the frame naturally appears at the conclusion of the natural development of the picture plane that begins with the creation of characters, the viewer is not particularly conscious of this. Breaking the “mold” refers to upsetting this balance or order. Unlike Okyo, Rosetsu began with the frame, whether protruding from or contained within it, and proceeded in the opposite direction of the arrows, arriving after a short period of intense activity at the creation of characters as a place where representation and brushwork compete.

Left: Nagasawa Rosetsu, Ghost, Edo period (18th century)

Right: Maruyama Okyo, Ghost, Edo period (18th century)

Accordingly, almost without exception, those viewing Rosetsu’s works from his mature period (from around the time of his stay in the Nanki area) are made aware of the frame before anything else. Rosetsu’s lines fluctuate boldly between the two extremes of precise outlines and vigorous strokes, but the things making this boldness possible are the frames. Rosetsu is always inside the frame. The price for breaking the “mold” was the “frame.” That one’s awareness of the frame never falters means that Rosetsu’s paintings are always “paintings of paintings.” This becomes clear if we compare Okyo’s

Ghost (cat. no. 13) with Rosetsu’s

Ghost (cat. no. 14), which have more or less the same composition. Rosetsu has produced a painting of a ghost, omitting not only the legs but also the bottom right hand corner of the frame. It is a picture of a scene in which the frame breaks down and the ghost escapes (is “characterized”) from the painting of a ghost. Okyo and Rosetsu, painting as painting and painting about painting. Simply placing the two side by side leaves no room for paintings to come.

Left: Nagasawa Rosetsu, A Pair of Puppies in Plum Blossoms, Edo period (18th century), Private collection

Right: Maruyama Okyo, Puppies, Edo period (1787)

*

At around the same time as the Rosetsu exhibition, a major Takeuchi Seiho retrospective was being held at the Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art. In other words, we were blessed with an opportunity to compare a Maruyama school artist from some 250 years ago with a Maruyama-Shijo school artist from some 130 years later, or around 130 years ago. The result of this comparison was astonishing. Because contrary to Seiho’s statement that “Only in the world of painting is it unjustified to keep on advocating for the expulsion of the barbarians and the closure of the ports; everything should be as open as possible and as much as possible should be imported. In this way, we should study the characteristics of ourselves and others, thereby plotting the progress of the arts,” since the studying of the past of 150 years ago, we have not learned a single new thing. What on earth are they saying was destroyed and what was created? Moreover, this was something that was predicted on the studying of the past of 250 years ago.

2 Because it would be safe to say that both painting as independent painting and painting about “independent painting” have long since been exhausted conceptually by Okyo and Rosetsu, who had been acquainted, albeit partially, with the ”West.”

Takeuchi Seiho, Tiger and Lion (left-hand screen), 1901, Mie Prefectural Art Museum

Takeuchi Seiho, Tiger and Lion (right-hand screen), 1901, Mie Prefectural Art Museum

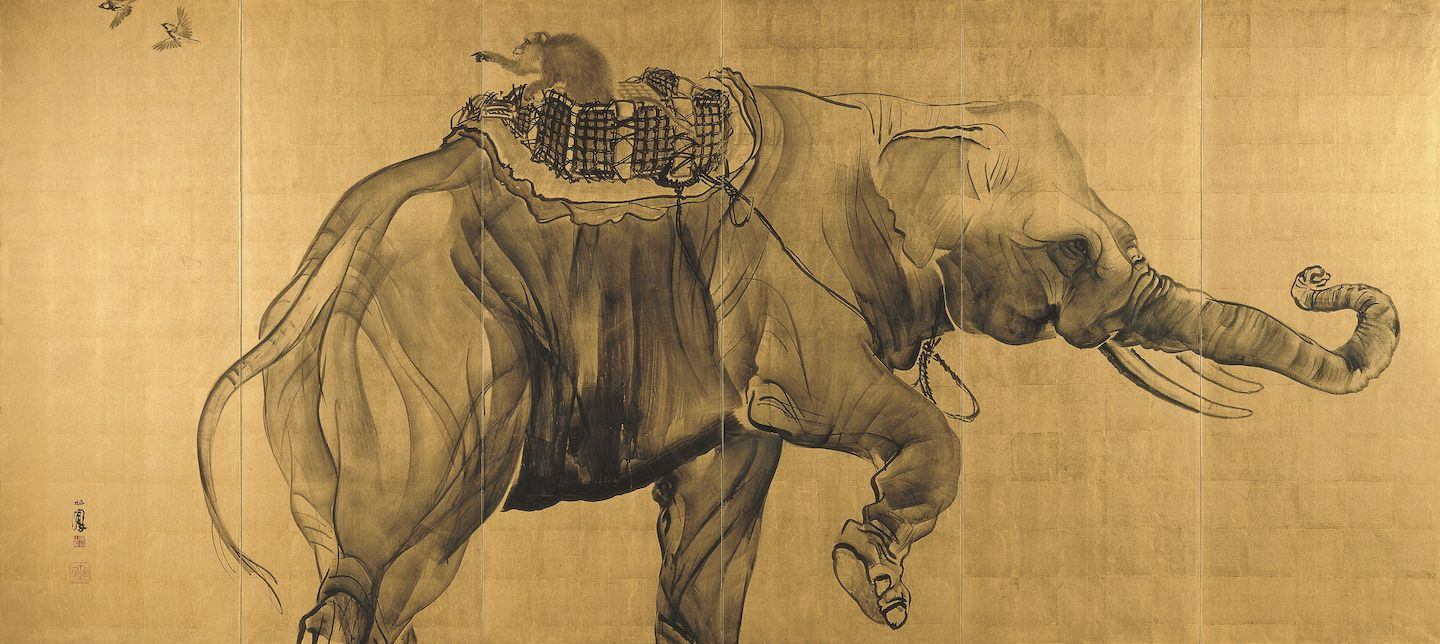

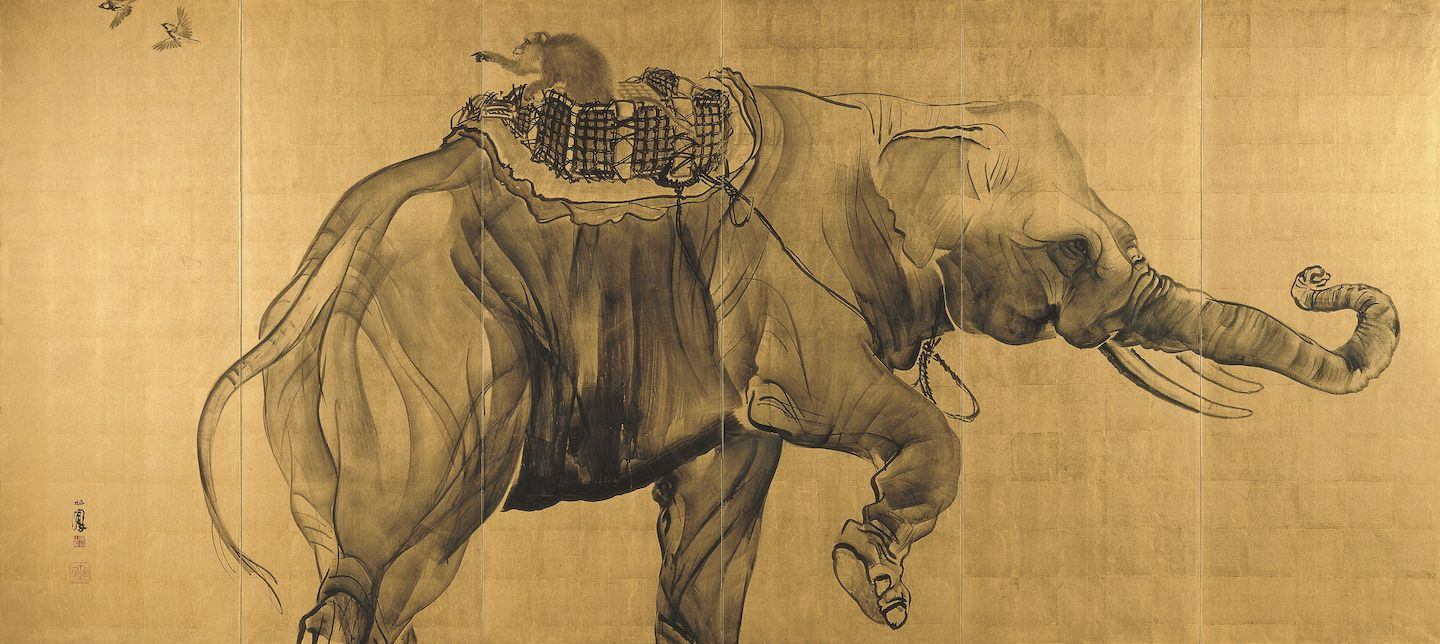

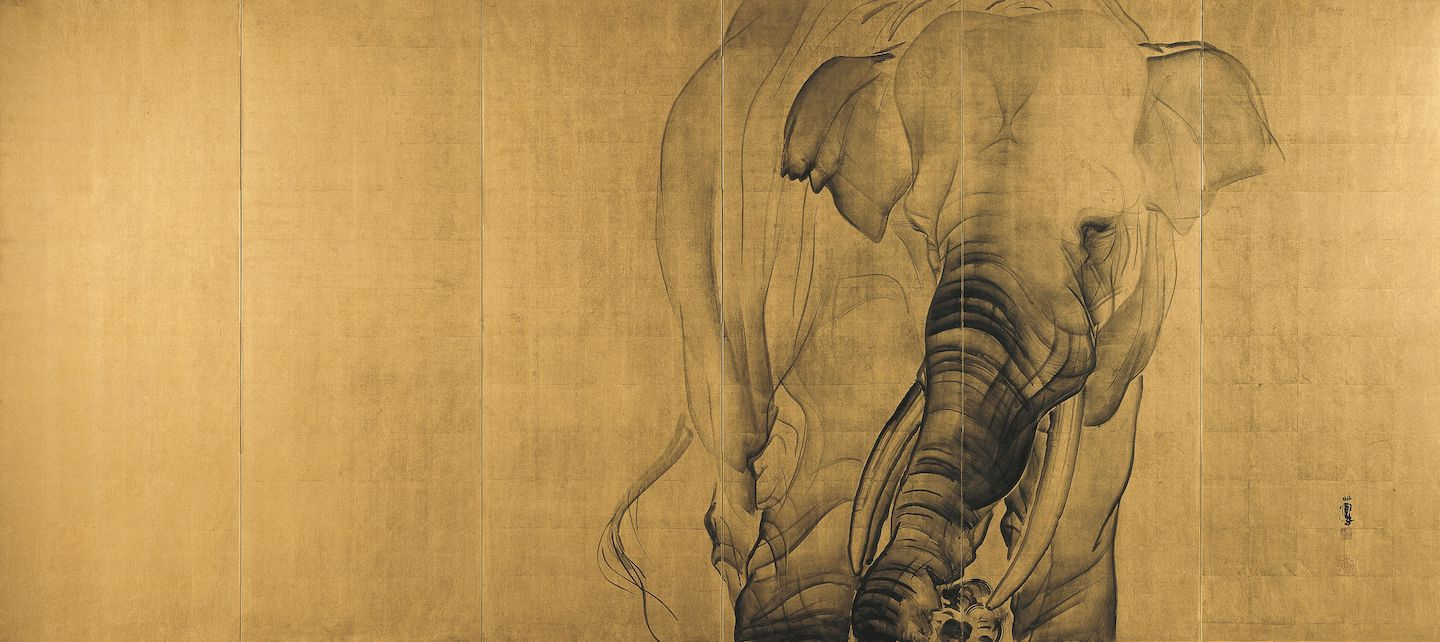

Takeuchi Seiho, Elephants (left-hand screen), c. 1904

(on view through November 19)

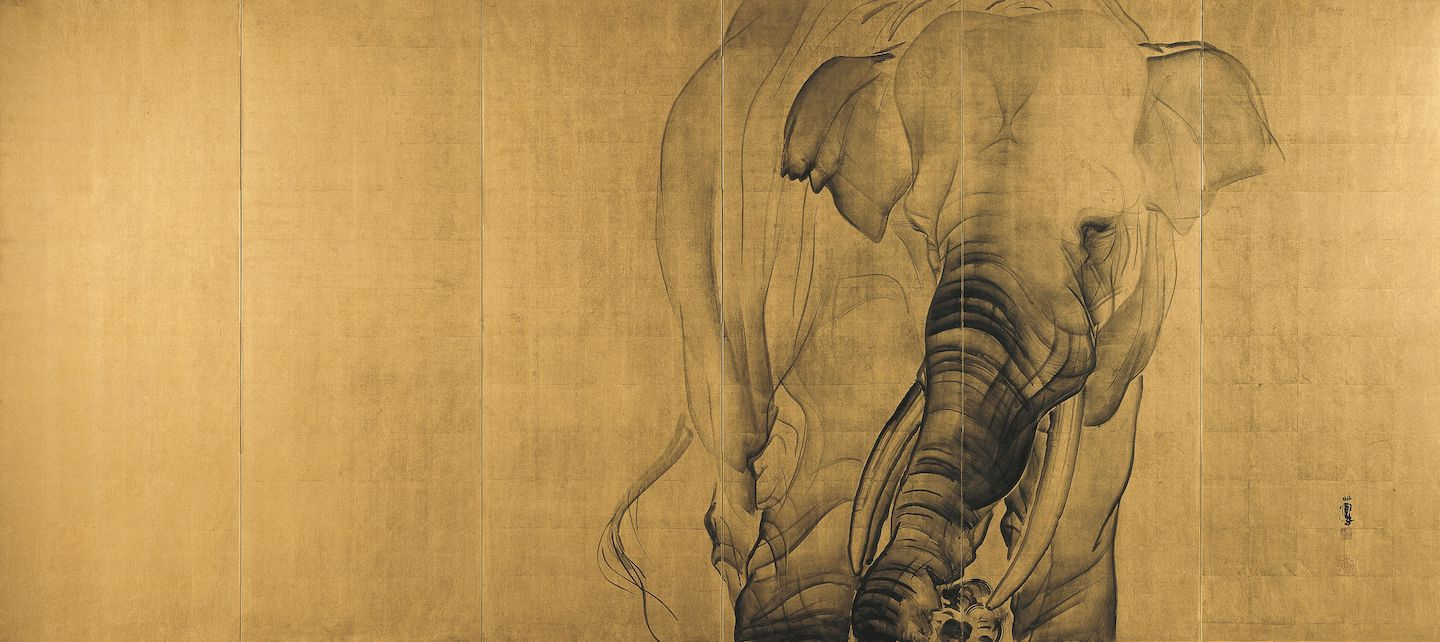

Takeuchi Seiho, Elephants (right-hand screen), c. 1904

(on view through November 19)

Seiho, who travelled to Europe and saw actual elephants, tigers and other animals in zoos there, painted these subjects in the Maruyama-Shijo school style that he had mastered, but the faces and coats are too close to the real things, which is to say they lean towards

shakei and are not

shasei in the true sense. Before they can become characters, his tigers are adulterated with a curious

gekiga (theatrical) touch, and one could say this ruins everything. Still,

Tiger and Lion (1901) and

Elephants (1904) are rendered with splendid brushstrokes using black and sepia ink on grounds of gold, greatly impressing viewers, although a later work,

Fierce Tiger (1930), resembles a kitsch stuffed toy and is almost an embarrassment. In general, the flowers, birds and animals rendered swiftly with flowing brushstrokes are superb, but the actual paintings are stiff and lack vitality.

Takeuchi Seiho, Fierce Tiger, 1930, Fukuda Art Museum

(on view through November 5)

Takeuchi Seiho, Maiko Dancing “Yamanba”, 1909, Takashimaya Archives

(on view through November 5)

Takeuchi Seiho, Posing for the First Time, 1913, Kyoto City Museum of Art

In the case of the figure paintings in particular—

Maiko Dancing “Yamanba” (1909),

Posing for the First Time (1913)—I cannot understand why they are regarded so highly. The latter appears to depict a scene inside a Japanese-style room in which the model (a geisha?), who is coy about becoming naked, is about to disrobe, but in fact the artist wanted to contrast the nude and the geometric pattern of the kimono, or perhaps he wanted to conjoin them (like Gustav Klimt, who was two years older than Seiho). In European terms, Seiho’s endeavors would be akin to an artist from the 1900s (Vilhelm Hammershøi and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (!) were born in 1864, the same year as Seiho, while Paul Signac and Klimt were a year and two years his senior respectively) being rated highly for producing 18th-century paintings. In other words, especially when it came to nihonga, it seems that the Kyoto of Seiho’s era was a backward world compared to the Kyoto of the 18th century.

——————————–

1. See Hashimoto Osamu, “Sono nanajuhachi: magarikado ni kiteita mono” [No. 78: That which had reached a turning point], Hiragana Nihon bijutsushi 5 [Hiragana Japanese art history 5] (Shinchosha, 2003), 51.

2. See the discussion of Okyo in “Sono nanajugo: ‘owari’ no hajimari to naru mono” [No. 75: What becomes the beginning of the “end”], ibid., 25.

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University.

“Takeuchi Seiho: A Destructive and Creative Force” is being held at

the Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art, and

“NAGASAWA ROSETSU: The Legendary Edo Master of Eccentric Painting” at

the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka, both until 3 December 2023.