Cultural Currency 19: "HIGASHIONNA Yuichi: behind the drapes" @ The Third Gallery Aya

The Showa era as “the uncanny” and its endless recurrence. The art of Higashionna Yuichi.

By Shimizu Minoru

2023.12.22

All photos courtesy of The Third Gallery Aya

The Japanese artists who made their international debuts in the 1980s and ’90s, which is to say the generation before 1989 (the year of the “Magiciens de la Terre” exhibition), when the post-colonial wave is considered to have arrived in the art world, gained international popularity by identifying with and presenting as “non-Western/colored/women and children” as seen from the perspective of the West, white people and men. Their methods involved appealing to symbolic stereotypes—“Hinomaru, Hirohito and Hiroshima” (the three Hs of PC Japan) or “Fujiyama, high-tech and JK (joshi kosei, or high school girls)” (FHJK as Japanese souvenirs!)—and because they involved identifying with a self reflected in the eyes of others, they naturally took on a masochistic aspect.

Higashionna Yuichi, who debuted just a short while after this group of artists, was refreshing in the sense that he used no such symbols at all. Rather, he directed his gaze at the invisible, inconspicuous details of Japanese society.

Explicitly political art simplifies actual politics. Real politics operate through an invisible network of power relationships, and the ideal state of politics is one in which no one is aware of the smooth functioning of this network, one in which everyone feels that the status quo is “natural,” like air. Intrinsically political art takes this state as its subject and reveals these hidden politics. The subjects Higashionna directed his attention to are the “fancy” taste that filled the rooms of the post-war Japanese middle class and the white light of fluorescent lamps.

During the period of rapid economic growth of the Showa era (1926–89), when the majority of Japanese residences changed from Japanese-style nagaya (row house) architecture typified by four-and-half-mat rooms and low dining tables to ready built Western-style architecture based on a living room and a dining room-cum-kitchen, one could occasionally see in the interiors of these residences goods and design one might describe as “fancy.” For Japanese at the time, unnatural bay windows on small houses, lace curtains, plastic artificial flowers, tissue boxes with frilly covers, and rugs, towels and slippers produced by Western designers (Pierre Cardin!) were considered “Western”-style details. In fact, however, such things were neither Western nor (literally) fancy, and resembled the pseudo-English words that exist only in Japan. Thus “fancy” signified not a copy of an original, but none other than a simulacra for which no original existed. As well, the living rooms and dining room-cum-kitchens in such houses were invariably illuminated by white light from ceiling-mounted fluorescent lamps. If Tanizaki Junichiro’s “In Praise of Shadows” represents the darkness of good old pre-war Japan, then the white light of fluorescent lamps represents the brightness that exemplified the middle class in democratic post-war Japan.

During the period of rapid economic growth of the Showa era (1926–89), when the majority of Japanese residences changed from Japanese-style nagaya (row house) architecture typified by four-and-half-mat rooms and low dining tables to ready built Western-style architecture based on a living room and a dining room-cum-kitchen, one could occasionally see in the interiors of these residences goods and design one might describe as “fancy.” For Japanese at the time, unnatural bay windows on small houses, lace curtains, plastic artificial flowers, tissue boxes with frilly covers, and rugs, towels and slippers produced by Western designers (Pierre Cardin!) were considered “Western”-style details. In fact, however, such things were neither Western nor (literally) fancy, and resembled the pseudo-English words that exist only in Japan. Thus “fancy” signified not a copy of an original, but none other than a simulacra for which no original existed. As well, the living rooms and dining room-cum-kitchens in such houses were invariably illuminated by white light from ceiling-mounted fluorescent lamps. If Tanizaki Junichiro’s “In Praise of Shadows” represents the darkness of good old pre-war Japan, then the white light of fluorescent lamps represents the brightness that exemplified the middle class in democratic post-war Japan.

Higashionna regards these subjects as examples of what Sigmund Freud referred to as “the uncanny” (das Unheimliche). In other words, the things post-war Japanese repressed into the unconscious are recurring as “fanciness” and “white light.” Needless to say, these repressed things are “defeat” and the decisive denial (“You’re not white!”) suffered by the Japanese who since the Meiji era have strived to modernize (i.e. quit Asia and join Europe, or become white, Western men). Higashionna has expressed these as objects emitting an excessive amount of white light (glittering chandeliers as “fancy” ornaments) and spray-paintings that call to mind the black shadows imprinted on walls in Hiroshima and Nagasaki due to radiation from the nuclear blasts.

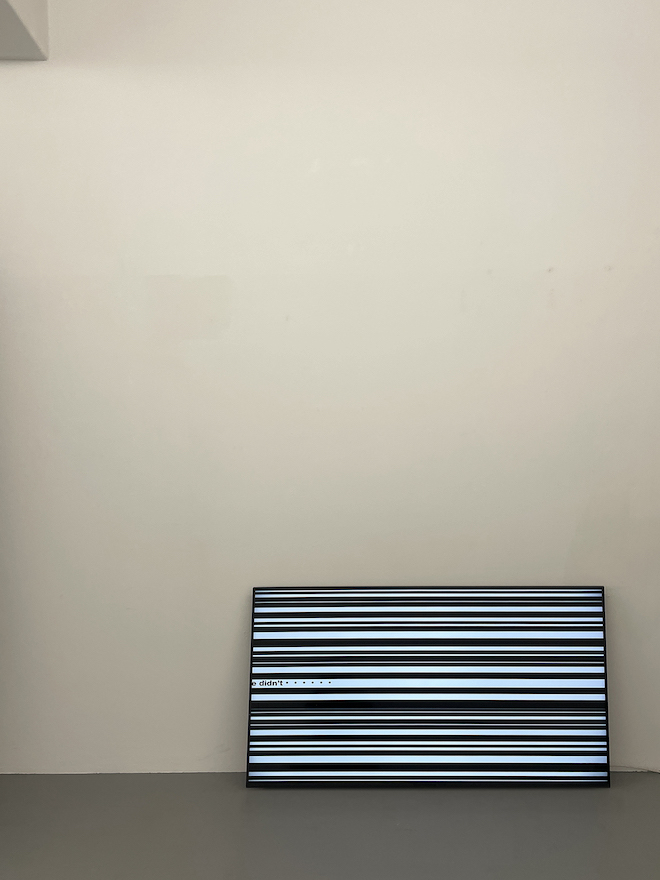

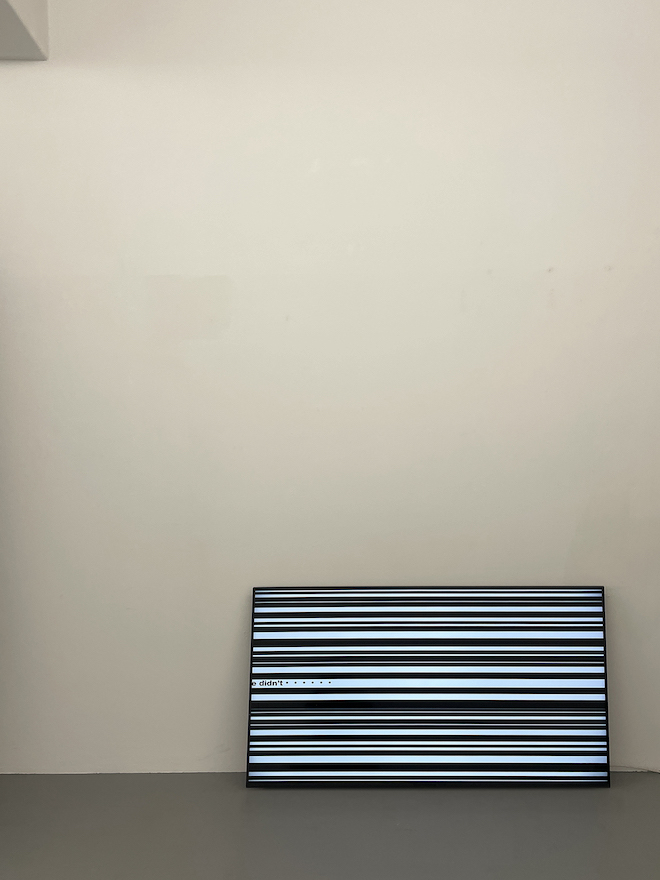

The white fluorescent lamp sculptures contained elements that transcended Higashionna’s early works as Japanese-made simulacra. Here, tacit political qualities met innovative op art that was different from the genre’s typical expression. Higashionna’s op art materialized as political intervention in an environment that at first glance seems natural. By regarding “nature” as an environment in which some sort of politics or system is concealed, exaggerating one of its characteristics (whiteness, for example) and reversing the light and darkness of the whole (i.e. creating a negative of that environment), he reveals the things lurking there. Exaggeration, reversal and distortion applied to certain spaces constitutes new op art. Here, the uncanny and beauty maintain a humorous balance.

Higashionna regards these subjects as examples of what Sigmund Freud referred to as “the uncanny” (das Unheimliche). In other words, the things post-war Japanese repressed into the unconscious are recurring as “fanciness” and “white light.” Needless to say, these repressed things are “defeat” and the decisive denial (“You’re not white!”) suffered by the Japanese who since the Meiji era have strived to modernize (i.e. quit Asia and join Europe, or become white, Western men). Higashionna has expressed these as objects emitting an excessive amount of white light (glittering chandeliers as “fancy” ornaments) and spray-paintings that call to mind the black shadows imprinted on walls in Hiroshima and Nagasaki due to radiation from the nuclear blasts.

The white fluorescent lamp sculptures contained elements that transcended Higashionna’s early works as Japanese-made simulacra. Here, tacit political qualities met innovative op art that was different from the genre’s typical expression. Higashionna’s op art materialized as political intervention in an environment that at first glance seems natural. By regarding “nature” as an environment in which some sort of politics or system is concealed, exaggerating one of its characteristics (whiteness, for example) and reversing the light and darkness of the whole (i.e. creating a negative of that environment), he reveals the things lurking there. Exaggeration, reversal and distortion applied to certain spaces constitutes new op art. Here, the uncanny and beauty maintain a humorous balance.

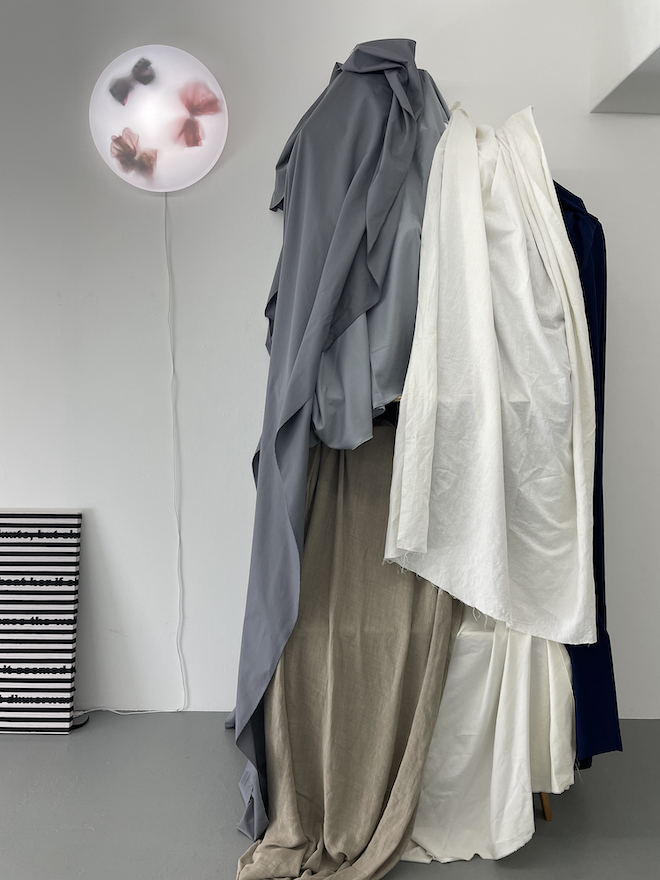

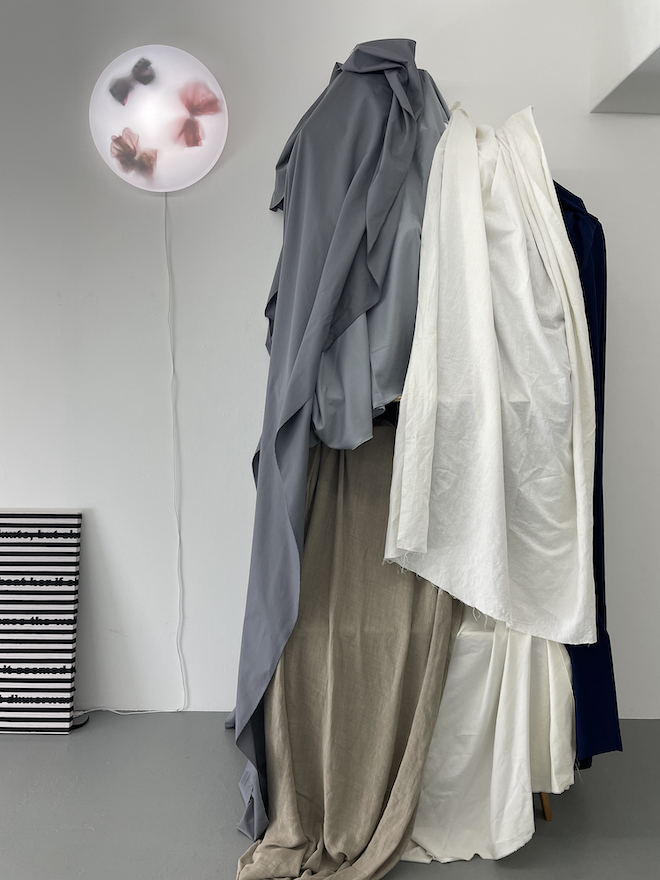

This is Higashionna’s first solo exhibition after parting ways with his former gallery and a gap of several years due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to the regular works discussed above, it showcases a new direction in the form of a retreat from color and fabric objects. The former is probably a temporary thing; the latter probably a product of the installations he has unveiled in recent years. Higashionna created several exhibits in actual fancy spaces under white light, namely Showa-era Western-style buildings that had deteriorated over half a century and that, despite being unoccupied, still retained signs or traces of their former residents. In these unoccupied houses, fabric dust covers were often placed over tables and other items of furniture. The wrinkles and folds of these covers drew in the bodies, objects and spaces they enveloped or concealed, in other words the absent past. Higashionna piled up and arranged fabric, the results calling to mind the obstinate depiction of drapery seen in Western traditional sculpture and painting, the canvases piled up in Lucian Freud’s studio and Wolfgang Tillmans’ “Faltenwurf” series. The Japanese words fuchi (arrangement), fukyo (missionary work), hanpu (distribution), rufu (circulation), fukoku (proclamation) and happu (promulgation) all use the kanji 布 (fu), meaning “fabric” but also “expanse” or “to extend,” perhaps due to the mental picture of unrolling a length of cloth. Is there anything in the Indo-European cultural sphere that corresponds to 布 (fu) in the kanji cultural sphere?

This is Higashionna’s first solo exhibition after parting ways with his former gallery and a gap of several years due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to the regular works discussed above, it showcases a new direction in the form of a retreat from color and fabric objects. The former is probably a temporary thing; the latter probably a product of the installations he has unveiled in recent years. Higashionna created several exhibits in actual fancy spaces under white light, namely Showa-era Western-style buildings that had deteriorated over half a century and that, despite being unoccupied, still retained signs or traces of their former residents. In these unoccupied houses, fabric dust covers were often placed over tables and other items of furniture. The wrinkles and folds of these covers drew in the bodies, objects and spaces they enveloped or concealed, in other words the absent past. Higashionna piled up and arranged fabric, the results calling to mind the obstinate depiction of drapery seen in Western traditional sculpture and painting, the canvases piled up in Lucian Freud’s studio and Wolfgang Tillmans’ “Faltenwurf” series. The Japanese words fuchi (arrangement), fukyo (missionary work), hanpu (distribution), rufu (circulation), fukoku (proclamation) and happu (promulgation) all use the kanji 布 (fu), meaning “fabric” but also “expanse” or “to extend,” perhaps due to the mental picture of unrolling a length of cloth. Is there anything in the Indo-European cultural sphere that corresponds to 布 (fu) in the kanji cultural sphere?

It goes without saying that in 2023, the tastes that lent color to the Showa era no longer exist. However, the Heisei era had its renditions of “fancy” and “white light,” and the Reiwa era has its own iterations. I say this because we are still living under the conditions of the Showa era: under the same constitution, the same emperor system and the same Japan-US Status of Forces Agreement. A repressed “Showa” continues to recur. And it may be that the focus of attention for this artist who continues to pursue this is now in the process of shifting from space to skin (touch).

——————————–

It goes without saying that in 2023, the tastes that lent color to the Showa era no longer exist. However, the Heisei era had its renditions of “fancy” and “white light,” and the Reiwa era has its own iterations. I say this because we are still living under the conditions of the Showa era: under the same constitution, the same emperor system and the same Japan-US Status of Forces Agreement. A repressed “Showa” continues to recur. And it may be that the focus of attention for this artist who continues to pursue this is now in the process of shifting from space to skin (touch).

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University. “HIGASHIONNA Yuichi: behind the drapes” is being held at The Third Gallery Aya until 23 December 2023.

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University. “HIGASHIONNA Yuichi: behind the drapes” is being held at The Third Gallery Aya until 23 December 2023.