Cultural Currency 21: "Heshiki Kenshichi: Lungs of a Goat"@The Third Gallery Aya

The depth of the sky (part 1)

By Shimizu Minoru

2024.02.29

Photo by Takashima Kiyotoshi

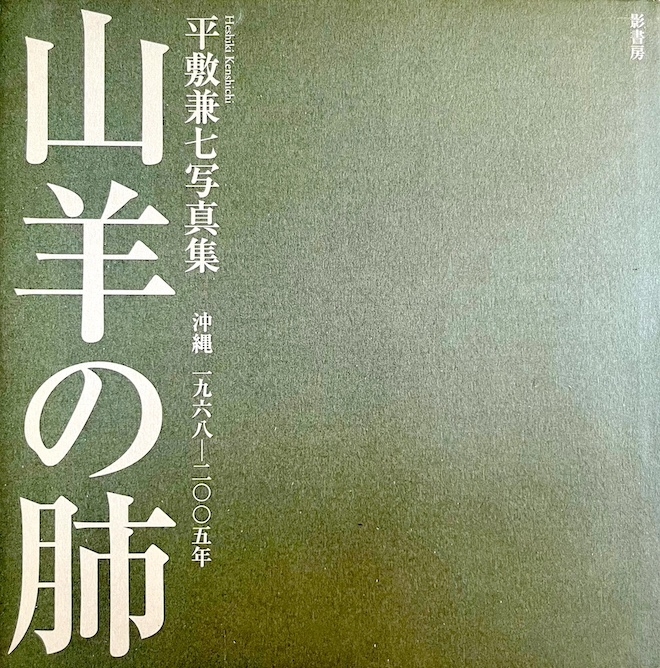

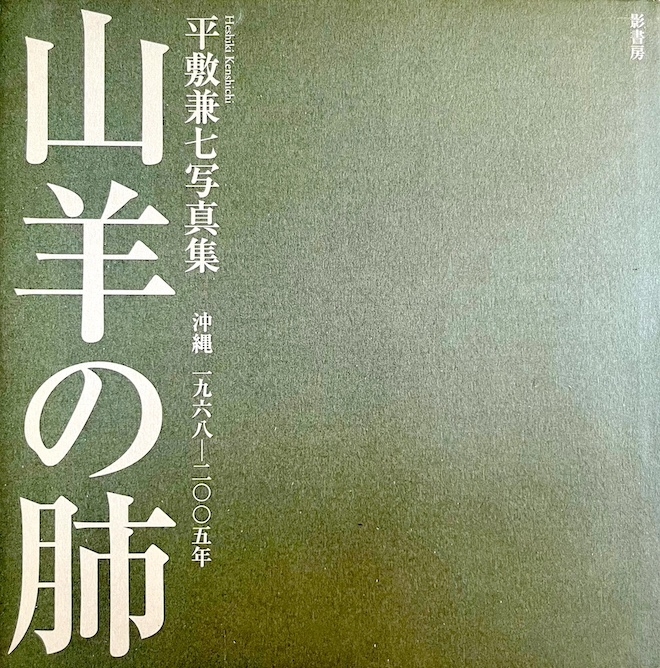

Heshiki Kenshichi (1948–2009) was an Okinawan photographer. Born in Okinawa when it was a U.S. territory, he “visited Japan” in the late 1960s to study photography at Tokyo Photography University and the Tokyo College of Photography, encountering contemporaneous photography, i.e. the work of photographers from “Contemporary Photographers” (1966) and “New Documents” (1967) onwards. Following the return of Okinawa to Japan, he took to photographing everyday scenes and the people of Okinawa and nearby islands, culminating in the publication of the photobook Yagi no hai (Lungs of a goat) in 2007. These images had a huge impact on the photography world and the following year, 2008, Heshiki received the Ina Nobuo Award, but he died suddenly in 2009 at the age of 61.

I first heard the name Heshiki Kenshichi in around 2007, and while I remember a collector friend of mine who liked Okinawa buying up his prints, in general he was an anonymous presence living an obscure life in the deep stratum that is Okinawan photography. He participated in such exhibitions as “Stunning Photographs of the Ryukyu Islands: Okinawa in Photographs” (Naha Civic Gallery, 2002), “Trajectory of Okinawan Culture 1872–2007” (Okinawa Prefectural Museum and Art Museum, 2007) and “Okinawa Prismed 1872–2008” (National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 2008), but he was not selected for inclusion in the nine-volume Okinawan photographers series Ryukyu retsuzo (Stunning photographs of the Ryukyu Islands). One could say it was not until the exhibition “For a New World to Come: Experiments in Japanese Art and Photography, 1968–1979” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (2015) that he became widely recognized as one of Okinawa’s leading photographers.

I first heard the name Heshiki Kenshichi in around 2007, and while I remember a collector friend of mine who liked Okinawa buying up his prints, in general he was an anonymous presence living an obscure life in the deep stratum that is Okinawan photography. He participated in such exhibitions as “Stunning Photographs of the Ryukyu Islands: Okinawa in Photographs” (Naha Civic Gallery, 2002), “Trajectory of Okinawan Culture 1872–2007” (Okinawa Prefectural Museum and Art Museum, 2007) and “Okinawa Prismed 1872–2008” (National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 2008), but he was not selected for inclusion in the nine-volume Okinawan photographers series Ryukyu retsuzo (Stunning photographs of the Ryukyu Islands). One could say it was not until the exhibition “For a New World to Come: Experiments in Japanese Art and Photography, 1968–1979” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (2015) that he became widely recognized as one of Okinawa’s leading photographers.

One characteristic cited by numerous scholars of Japanese post-war photography/film both in Japan and overseas is realism.1 Beginning with the “social” realism of the 1950s, continuing with the “objective” realism of the 1960s and the “expressionist” realism of Provoke and extending up until the mid 1970s, the photographers and documentary filmmakers of this period tirelessly pursued and engaged in lively debate on the subject of realism. Passion for “real things” is certainly a characteristic of post-war Japanese photography. The magic words aru ga mama (as it is) obsessed photographers. The style of the photojournalism of the 1950s (“beggar photography”), the surrealistic expression of the members of the Vivo cooperative and the furious are-bure-boke (rough, blurred and out-of-focus) style of the photographic records of the Anpo protests (Hamaya Hiroshi, Watanabe Hitomi, Kitai Kazuo) and Provoke were all methods of exposing “real things.” If this kind of hysteria with regard to “reality as it is” stems from a historical context peculiar to Japan, then this, though limited to the post-war era, is probably the essence of “Japanese.”

Due to the accumulation of Japanese post-war historical research, the historical context that gave rise to this passion for “reality” in Japan has already been brought to light and is not a particularly new thing. Historian Igarashi Yoshikuni calls it the “foundational narrative” of post-war Japan-U.S. relations.2 This is a kind of melodrama and resembles the pattern in which a man slaps a woman he loves and she interprets this together with the pain as an expression of deep affection. Here, the man is the U.S., the “slap” is the dropping of the atomic bombs (a forehand-backhand slap in the face!) and the woman is Japan. It was President Truman who decided to use atomic bombs to end the war, which roused Emperor Hirohito to bring the war to a close with his “imperial decision,” so the decisions by these two great men regarding atomic bombs put an end to the disastrous war and saved Japan. In short, this narrative denied the trauma of Japan’s defeat (what Shirai Satoshi calls the “permanent defeat”3) and, in exchange for accepting the structure of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty with the U.S. in a dominant position, preserved the “national polity” of the emperor system.4

One characteristic cited by numerous scholars of Japanese post-war photography/film both in Japan and overseas is realism.1 Beginning with the “social” realism of the 1950s, continuing with the “objective” realism of the 1960s and the “expressionist” realism of Provoke and extending up until the mid 1970s, the photographers and documentary filmmakers of this period tirelessly pursued and engaged in lively debate on the subject of realism. Passion for “real things” is certainly a characteristic of post-war Japanese photography. The magic words aru ga mama (as it is) obsessed photographers. The style of the photojournalism of the 1950s (“beggar photography”), the surrealistic expression of the members of the Vivo cooperative and the furious are-bure-boke (rough, blurred and out-of-focus) style of the photographic records of the Anpo protests (Hamaya Hiroshi, Watanabe Hitomi, Kitai Kazuo) and Provoke were all methods of exposing “real things.” If this kind of hysteria with regard to “reality as it is” stems from a historical context peculiar to Japan, then this, though limited to the post-war era, is probably the essence of “Japanese.”

Due to the accumulation of Japanese post-war historical research, the historical context that gave rise to this passion for “reality” in Japan has already been brought to light and is not a particularly new thing. Historian Igarashi Yoshikuni calls it the “foundational narrative” of post-war Japan-U.S. relations.2 This is a kind of melodrama and resembles the pattern in which a man slaps a woman he loves and she interprets this together with the pain as an expression of deep affection. Here, the man is the U.S., the “slap” is the dropping of the atomic bombs (a forehand-backhand slap in the face!) and the woman is Japan. It was President Truman who decided to use atomic bombs to end the war, which roused Emperor Hirohito to bring the war to a close with his “imperial decision,” so the decisions by these two great men regarding atomic bombs put an end to the disastrous war and saved Japan. In short, this narrative denied the trauma of Japan’s defeat (what Shirai Satoshi calls the “permanent defeat”3) and, in exchange for accepting the structure of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty with the U.S. in a dominant position, preserved the “national polity” of the emperor system.4

“Japanese photography” is photography in Japan from the 1950s to the present that obsessively continues to pursue “reality as it is” in the context of a “national polity” that is in fact a soft colonial system based on the bilateral cooperation between the imperial family, whose position was guaranteed in the U.S.-drafted constitution, and the U.S., which occupies a dominant position in the Japan-U.S. Status of Forces Agreement.5

“Japanese photography” is photography in Japan from the 1950s to the present that obsessively continues to pursue “reality as it is” in the context of a “national polity” that is in fact a soft colonial system based on the bilateral cooperation between the imperial family, whose position was guaranteed in the U.S.-drafted constitution, and the U.S., which occupies a dominant position in the Japan-U.S. Status of Forces Agreement.5

——————————–

——————————–

1. Yuriko Furuhata, Cinema of Actuality: Japanese avant-garde filmmaking in the season of image politics (Duke University Press, 2013); Kai Yoshiaki, Arinomama no imēji: sunappu bigaku to nihonshashinshi [As-it-is images: Snapshot aesthetics and the history of Japanese photography] (University of Tokyo Press, 2021). 2. Igarashi Yoshikuni, Bodies of memory: narratives of war in postwar Japanese culture, 1945-1970 (Princeton University Press, 2012). 3. Shirai Satoshi, Eizoku haisenron: sengo Nihon no kakushin [Theory of permanent defeat: the heart of post-war Japan] (Ohta Publishing, 2013). 4. Katayama Morihide, Mikan no fashizumu: “motazaru kuni” Nihon no unmei [Unfinished fascism: Japanese fate, a “country without”] (Shinchosha, 2012); Kuni no shinikata [How a country dies] (Shinchosha, 2012). We should probably not forget that the position of the emperor is guaranteed under the U.S.-drafted constitution. 5. Accordingly, the famous photo of Emperor Hirohito and General MacArthur that shocked the post-war Japanese should probably be considered the starting point of “Japanese photography.”

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University. “Heshiki Kenshichi: Lungs of a Goat” was held at The Third Gallery Aya from January 27 to February 24, 2024.

Heshiki Kenshichi, Yagi no Hai (Lungs of a goat), published in 2007

*

If some kind of inherent nature is implied by the adjective “Japanese” in “Japanese photography,” what might it be? Replying that “Japanese photography” refers to photographs taken in Japan by artists with Japanese nationality does not answer the question. To think that inherent characteristics dwell within photographs taken by people with Japanese nationality, almost as if they were genetic factors, is nothing but racism, and to insist stubbornly that if one merely takes photographs in Japan this inherent nature will be reflected is simply idiotic. The inherent nature implied by the word “Japan” cannot be nationality or the location where the photographs are taken. To begin with, because since the late 19th century photography has been a global, contemporaneous medium, an essentialist approach is impossible. It is possible to argue that one can see in late Edo-period photography a continuity with the composition of ukiyo-e, but because ukiyo-e also had an influence on European painters and photographers, there is also continuity there. Moreover, because the question of essentialism itself has a colonialist tendency, though it can be found in essentialist terms, “Japanese essence” probably lapses automatically into such stereotypes as ku (void) and ma (space). It is for this reason that Karen M. Fraser’s Photography and Japan (2011), for example, eschews the term “Japanese photography” and adopts the approach of asking how “Japan” and “photography” have been concerned with each other historically. According to Fraser, the three guiding threads of “identity,” “war” and “the city” most clearly reveal the relationship between Japan and photography. Though I have no objection to this, surely the same approach could be applied to any country that has questioned its identity as a nation state (or in the process has been afflicted by the colonial comparative thinking of “Europe and my country”), passed through the age of war that was the 20th century and developed an urban culture (photography and the U.S., photography and Turkey, photography and Mexico, and so on). If one is defining “Japanese,” something that applies only to Japan, then the characteristics found there must be conditioned by a historical context that is peculiar to Japan.

Installation views of “Heshiki Kenshichi: Lungs of a Goat”

Photos by Takashima Kiyotoshi

Emperor Hirohito and General MacArthur at their first meeting, the U.S. Embassy, Tokyo, 27 September, 1945. Photo by Gaetano Faillace

Installation view of “Heshiki Kenshichi: Lungs of a Goat”

Photo by Takashima Kiyotoshi

1. Yuriko Furuhata, Cinema of Actuality: Japanese avant-garde filmmaking in the season of image politics (Duke University Press, 2013); Kai Yoshiaki, Arinomama no imēji: sunappu bigaku to nihonshashinshi [As-it-is images: Snapshot aesthetics and the history of Japanese photography] (University of Tokyo Press, 2021). 2. Igarashi Yoshikuni, Bodies of memory: narratives of war in postwar Japanese culture, 1945-1970 (Princeton University Press, 2012). 3. Shirai Satoshi, Eizoku haisenron: sengo Nihon no kakushin [Theory of permanent defeat: the heart of post-war Japan] (Ohta Publishing, 2013). 4. Katayama Morihide, Mikan no fashizumu: “motazaru kuni” Nihon no unmei [Unfinished fascism: Japanese fate, a “country without”] (Shinchosha, 2012); Kuni no shinikata [How a country dies] (Shinchosha, 2012). We should probably not forget that the position of the emperor is guaranteed under the U.S.-drafted constitution. 5. Accordingly, the famous photo of Emperor Hirohito and General MacArthur that shocked the post-war Japanese should probably be considered the starting point of “Japanese photography.”

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University. “Heshiki Kenshichi: Lungs of a Goat” was held at The Third Gallery Aya from January 27 to February 24, 2024.