Cultural Currency 22: "Heshiki Kenshichi: Lungs of a Goat"@The Third Gallery Aya

The depth of the sky (part 2)

By Shimizu Minoru

2024.03.29

The spell of “as it is.” Why a spell?

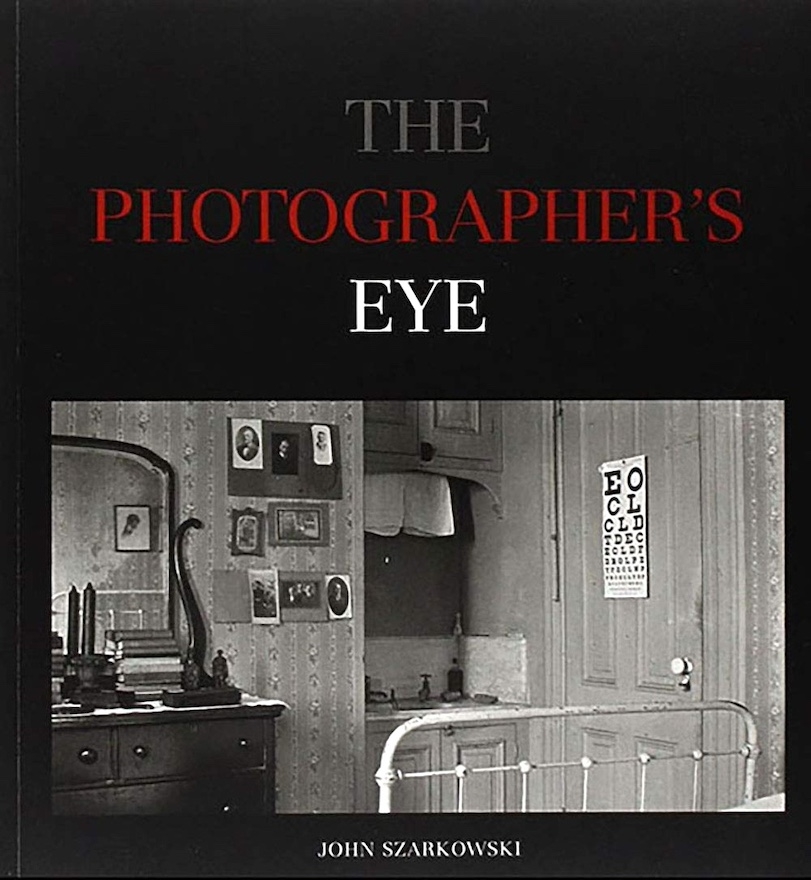

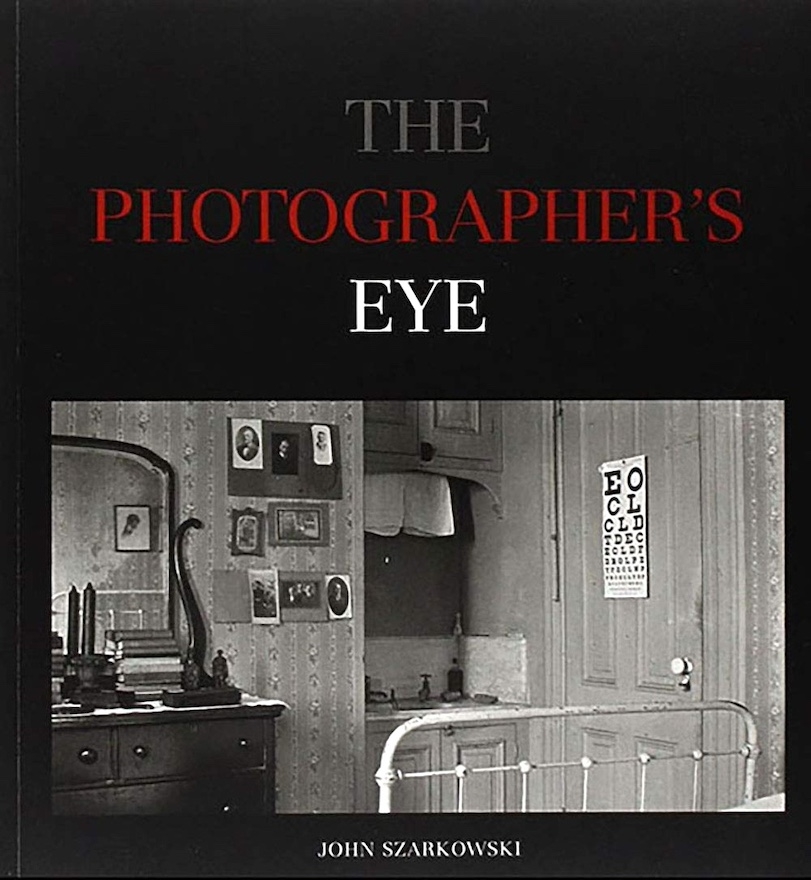

“Our faith in the truth of a photograph rests on our belief that the lens is impartial, and will draw the subject as it is, neither nobler nor meaner.” (John Szarkowski, The Photographer’s Eye, 1966) Realist discourse is based on a belief that considers being “as it is” absolutely right and aims to transcend such dualist frameworks as beauty and ugliness, right and wrong, superior and inferior, and high and low social standing. A variation on this discourse, which emerged together with straight photography in the 1910s, was played by Surrealism in the 1920s and 30s in the form of “exposure discourse” (or “naked discourse”). This was based on the belief that reality consists of normal reality and surreality (true reality, or reality “as it is”), with the latter hidden beneath the surface layer of the former, waiting to be exposed by the human effort (creation) of artists. As a result, the contradiction between the unavoidable human effort involved in shooting, developing and selecting photographs and the “as it is-ness” that was demanded was resolved, and the genre known as “documentary” developed in various ways.

However, when we apply this standard realist discourse to Japan during the occupation, a contradiction arises. The “naked” Japan “as it is” that needed to be exposed was none other than the artificial constraint that was occupied Japan. Moreover, the Treaty of San Francisco further strengthened this contradiction. A condition for ending the occupation was the addition of more fetters in the form of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. This meant “Japan as it is” being incorporated under U.S. control into the anti-communist front in the east under the Cold War regime, at which time Okinawa was like a collar ensuring Japan did not draw close to the Soviet Union or China (the so-called Dulles Intimidation of 1956).

However, when we apply this standard realist discourse to Japan during the occupation, a contradiction arises. The “naked” Japan “as it is” that needed to be exposed was none other than the artificial constraint that was occupied Japan. Moreover, the Treaty of San Francisco further strengthened this contradiction. A condition for ending the occupation was the addition of more fetters in the form of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty. This meant “Japan as it is” being incorporated under U.S. control into the anti-communist front in the east under the Cold War regime, at which time Okinawa was like a collar ensuring Japan did not draw close to the Soviet Union or China (the so-called Dulles Intimidation of 1956).

The “outside” (the surreal world as it is) supposed by realist discourse can by definition only be a projection of the “inside” (the normal real world) on the outside. However, because in post-war/occupied Japan, traditional Japan (that which had been irreversibly discarded at the time of the Meiji Restoration) and modernized Japan (the Empire of Japan founded on the basis of the slogan “Leave Asia, Enter Europe”) have been thoroughly destroyed, and even the new Japan (the “national polity” of the U.S. and the imperial family) is nothing but a colonial fiction of these two, such a projection is impossible. It is from this that the absence of an “outside” arises. Having been colonized under the Cold War regime means having been robbed of “as it is-ness.” It is said that one of the characteristics of post-war Japanese photography is realism. But this is a negative realism deprived of “real” “as it is-ness” and wields the power of a strong spell on account of the endlessness of longing for something that does not exist.

The “outside” (the surreal world as it is) supposed by realist discourse can by definition only be a projection of the “inside” (the normal real world) on the outside. However, because in post-war/occupied Japan, traditional Japan (that which had been irreversibly discarded at the time of the Meiji Restoration) and modernized Japan (the Empire of Japan founded on the basis of the slogan “Leave Asia, Enter Europe”) have been thoroughly destroyed, and even the new Japan (the “national polity” of the U.S. and the imperial family) is nothing but a colonial fiction of these two, such a projection is impossible. It is from this that the absence of an “outside” arises. Having been colonized under the Cold War regime means having been robbed of “as it is-ness.” It is said that one of the characteristics of post-war Japanese photography is realism. But this is a negative realism deprived of “real” “as it is-ness” and wields the power of a strong spell on account of the endlessness of longing for something that does not exist.

Until 1972 Okinawa was a U.S. territory, so it was indeed under the absolute control of the American military as a result of Japan’s defeat, but it was free from this kind of “national polity.” Out of range of the effect of the narrative that denied Japan’s defeat, Okinawa literally lost everything and fell as far as it could go. If Japanese photography was put under the spell of “as it is-ness” inside the “national polity” and dreamed of a nonexistent “as it is,” then Okinawan photography lost all its dreams.

Until 1972 Okinawa was a U.S. territory, so it was indeed under the absolute control of the American military as a result of Japan’s defeat, but it was free from this kind of “national polity.” Out of range of the effect of the narrative that denied Japan’s defeat, Okinawa literally lost everything and fell as far as it could go. If Japanese photography was put under the spell of “as it is-ness” inside the “national polity” and dreamed of a nonexistent “as it is,” then Okinawan photography lost all its dreams.

——————————–

——————————–

1. Among Heshiki’s works, for example, one can see in the frontal composition and the use of subjects with atypical appearances (people with mental disabilities, etc.) the influence of Diane Arbus, but the former is natural for portraits (one could probably say this if Heshiki—like Kikai Hiroh, who was three years his senior—had frequently used the square format that Arbus made habitual use of, but such works are absent from Yagi no hai (Lungs of a Goat) and there are just a few examples of the latter among all of the works. 2. See Shimizu Minoru, “Puroboku to konpora—’Nihon shashin no 1968’ ten” [Provoke and konpora—the “1968—Japanese Photography” exhibition] in Dijitaru shashin ron [On digital photography] (University of Tokyo Press, 2021).

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University. “Heshiki Kenshichi: Lungs of a Goat” was held at The Third Gallery Aya from January 27 to February 24, 2024.

John Szarkowski, The Photographer’s Eye, 1966

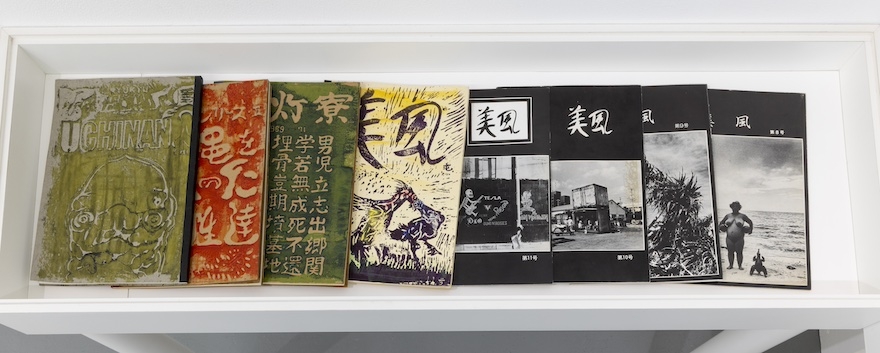

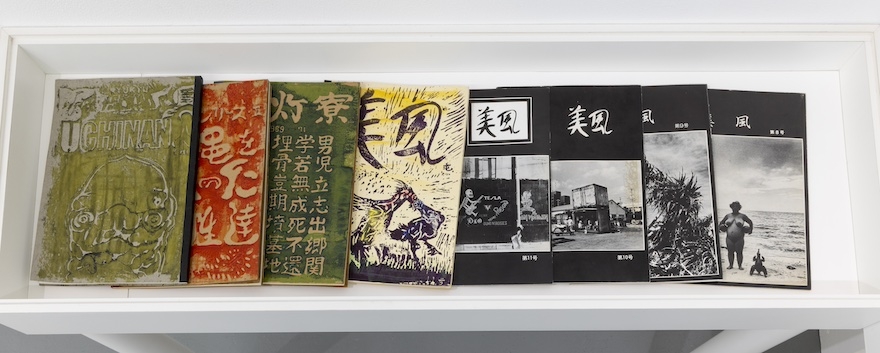

Installation views of “Heshiki Kenshichi: Lungs of a Goat”

Photos by Takashima Kiyotoshi

From Heshiki Kenshichi’s “Lungs of a Goat” series

*

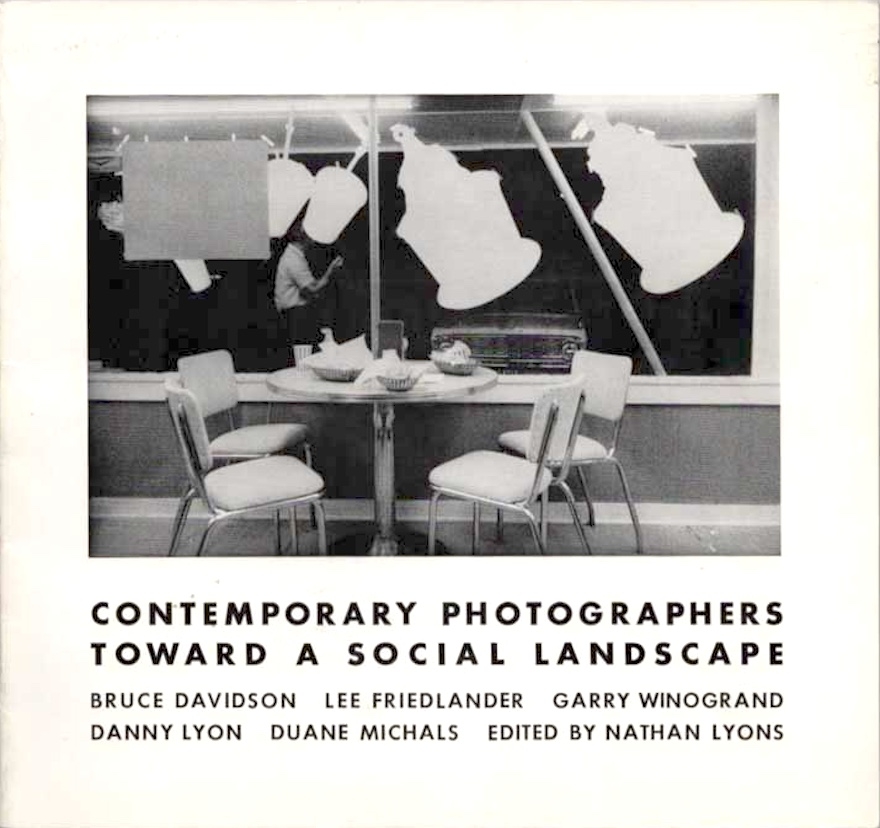

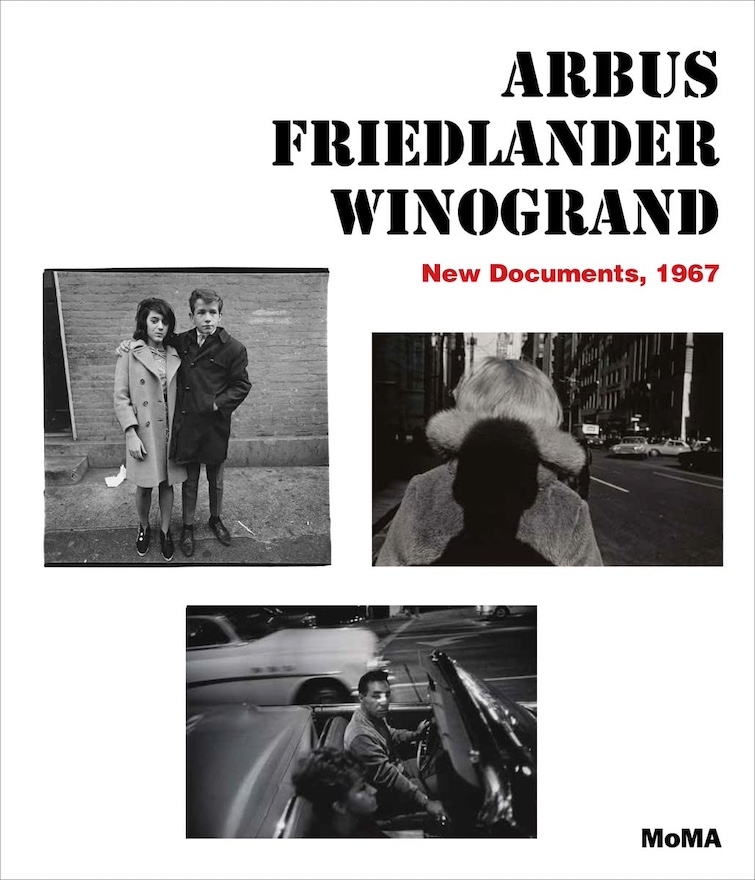

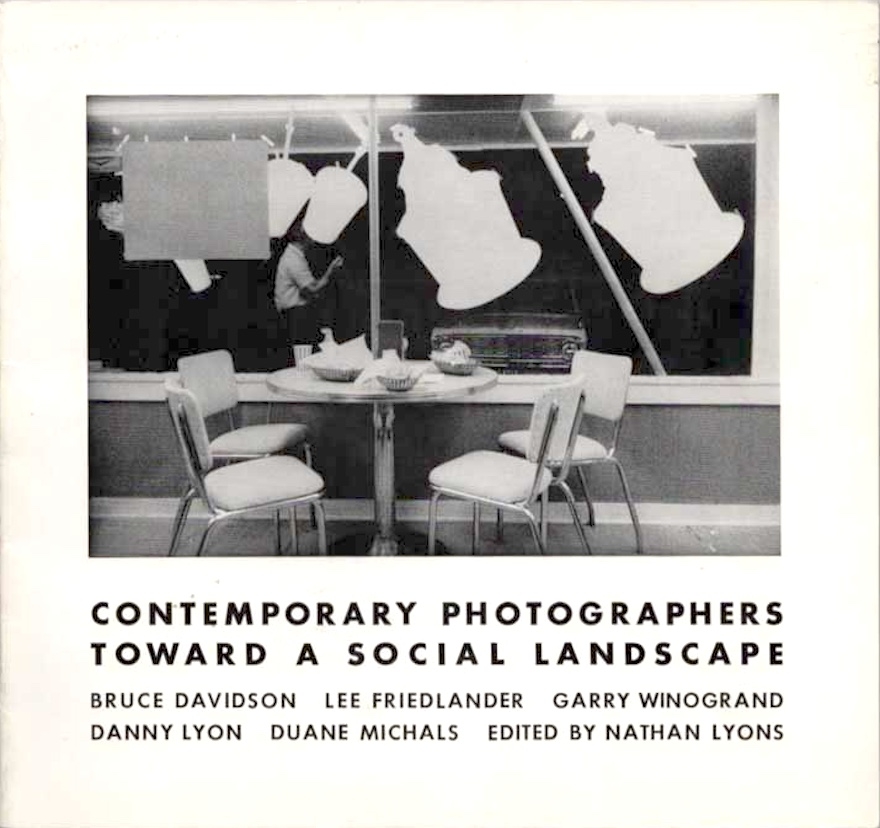

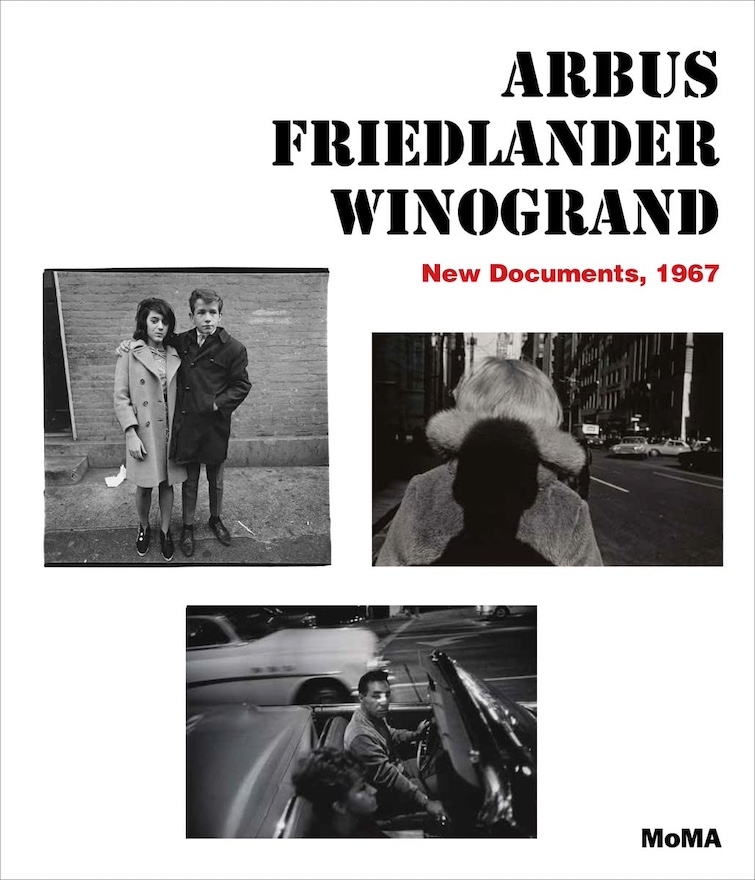

At the beginning of Part 1, I wrote that having moved to Tokyo, Heshiki came “into contact with contemporaneous photography, or the work of photographers from ‘Contemporary Photographers’ (1966) and ‘New Documents’ (1967) onwards.” The substance of this influential relationship is difficult to estimate,1 but in any event the result was “post-realist” photography, which means that it was photography devoid of the aforementioned belief that considers being “as it is” absolutely right, and furthermore that it was photography that did not adopt the methodology of “exposing the ‘reality as it is’ hidden behind normal reality.” This is none other than the heart of what was then called konpora (contemporary photography).2 In other words, one could probably say that Heshiki Kenshichi’s photography ought to occupy a position close to konpora photography. (To be continued)

Nathan Lyons, ed., Contemporary Photographers Toward a Social Landscape: Bruce Davidson, Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, Danny Lyons, Duane Michals, 1966

Arbus Friedlander Winogrand, New Documents, 1967

1. Among Heshiki’s works, for example, one can see in the frontal composition and the use of subjects with atypical appearances (people with mental disabilities, etc.) the influence of Diane Arbus, but the former is natural for portraits (one could probably say this if Heshiki—like Kikai Hiroh, who was three years his senior—had frequently used the square format that Arbus made habitual use of, but such works are absent from Yagi no hai (Lungs of a Goat) and there are just a few examples of the latter among all of the works. 2. See Shimizu Minoru, “Puroboku to konpora—’Nihon shashin no 1968’ ten” [Provoke and konpora—the “1968—Japanese Photography” exhibition] in Dijitaru shashin ron [On digital photography] (University of Tokyo Press, 2021).

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University. “Heshiki Kenshichi: Lungs of a Goat” was held at The Third Gallery Aya from January 27 to February 24, 2024.