Given that I first learned all about Fukuda Heihachiro 17 years ago at

the 2007 retrospective at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, I made my way to the Nakanoshima Museum of Art with few expectations, thinking that this latest show might even be a waste of time. However, that

“Claude Monet: Journey to Series Paintings” was being held at the museum at the same time turned out to be a fortunate coincidence, because with the aid of Claude Monet (1840–1926) I was able to better understand the painter Fukuda Heihachiro (1892–1974).

Before I continue, let us review some things, beginning with Monet’s Water Lilies. Reflections of a sky that changes color moment by moment, of white clouds, and of trees on the water’s edge fill the picture planes, and on top of these are arranged water lilies. As a result, the viewer becomes conscious of the surface of the water on which the lilies float. It is as if all the beautiful reflections that fill the picture planes are images on top of these surfaces. By approaching the surface of the water, something that is usually invisible, from both sides with the reflected scenery and the water lilies, Monet makes it appear without painting the water itself. It was these surfaces that are themselves nonmaterial and invisible, the very basal planes that underpin all visible images (paintings), that Monet pursued in his later years. These surfaces represented the essence of Western painting in that they were in olden times the projection planes of linear perspective, were later perfected as “layers” in the age of the camera obscura, and were dubbed by Clement Greenberg “flatness” in the form of “a strictly pictorial, strictly optical third dimension.”

Claude Monet, The Water Lilies – Setting Sun, 1920–1926, Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris

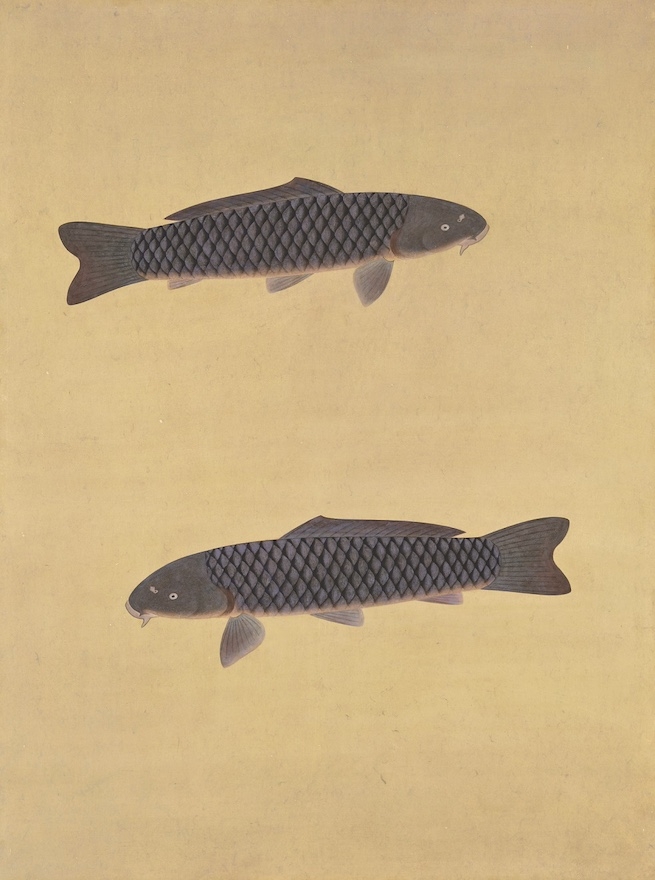

In other words, using the reflections of scenery and water lilies, Monet painted the surface of water (a layer) without painting the water itself. Interestingly, Fukuda Heihachiro says a similar thing about

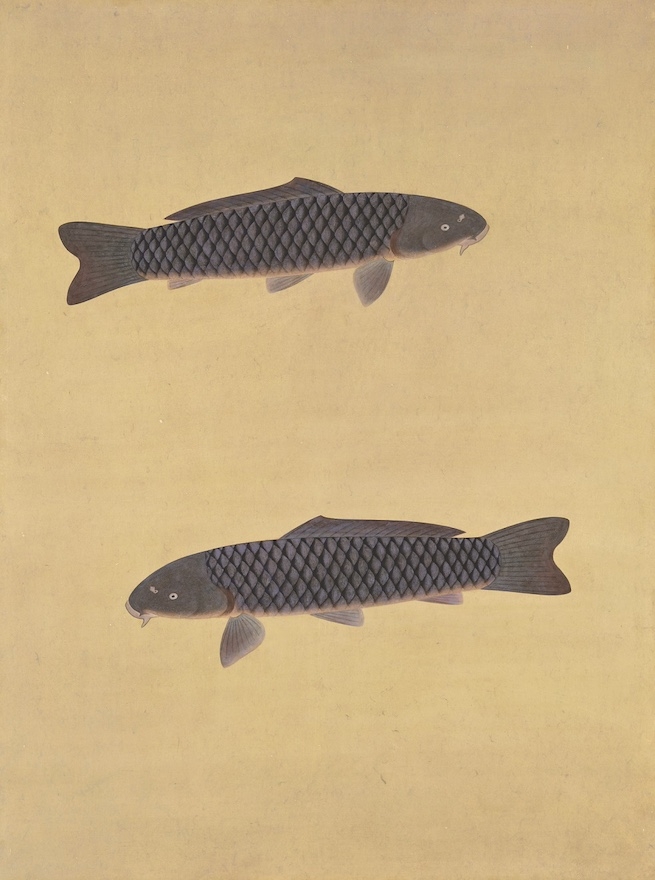

Carp (1921, The Museum of the Imperial Collections, Sannomaru Shozokan), regarded as the painter’s de facto debut work with which he established himself as an artist.

“Here, because I fully achieved realism, I reached the point where for the first time I thought painting carp clearly without the concept of water was not frightening.… However, it was a difficult decision to make, and even in this case I wavered until the very end over whether to include water or not, going as far as preparing green-gold to apply as the water. It was not until the last moment that I decided to leave it as it was.”

1

Carp (1921, The Museum of the Imperial Collections, Sannomaru Shozokan)

is not a picture of carp, but a picture of water. Moreover, unlike Monet, Heihachiro has painted water solely by painting carp (and the bottom of the water via the shadows cast by the carp).

Carp (c. 1923, Namikawa Cloisonné Museum of Kyoto)

Rendition of solely the carp, no shadows: Carp (1954, Hiraki Ukiyo-e Foundation)

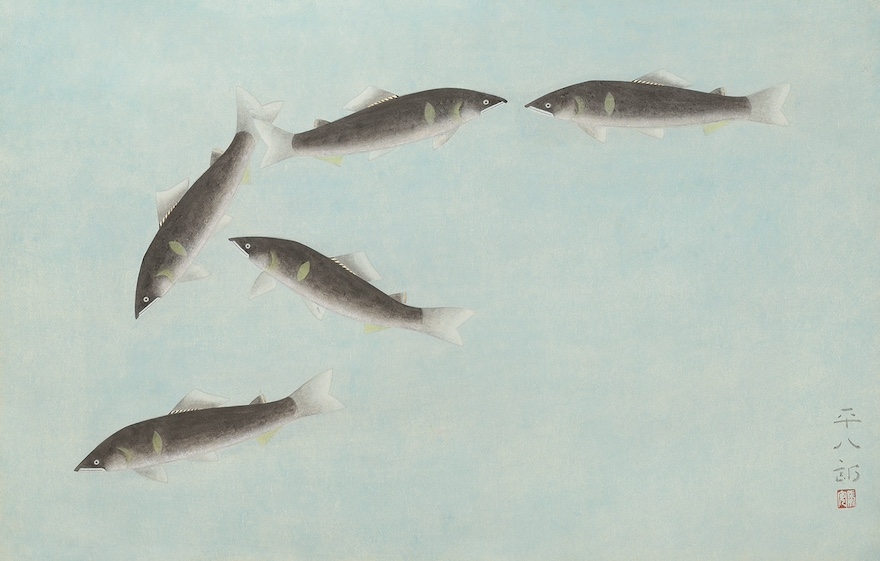

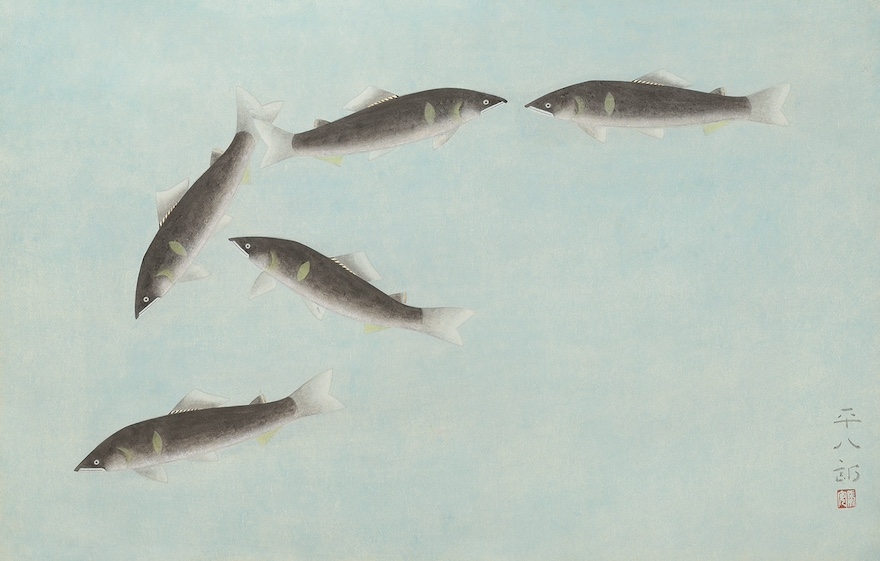

In lieu of carp: Sweetfish (1958, Oita Art Museum)

For Heihachiro, the determination to not paint water was a precarious thing. For example, already in the hanging scroll

Carp (1921) produced the same year, there is the depiction of the surface of the water via ripples generated by carp swarming around food. It is unclear whether Heihachiro had seen Monet’s water lilies at this time, but in

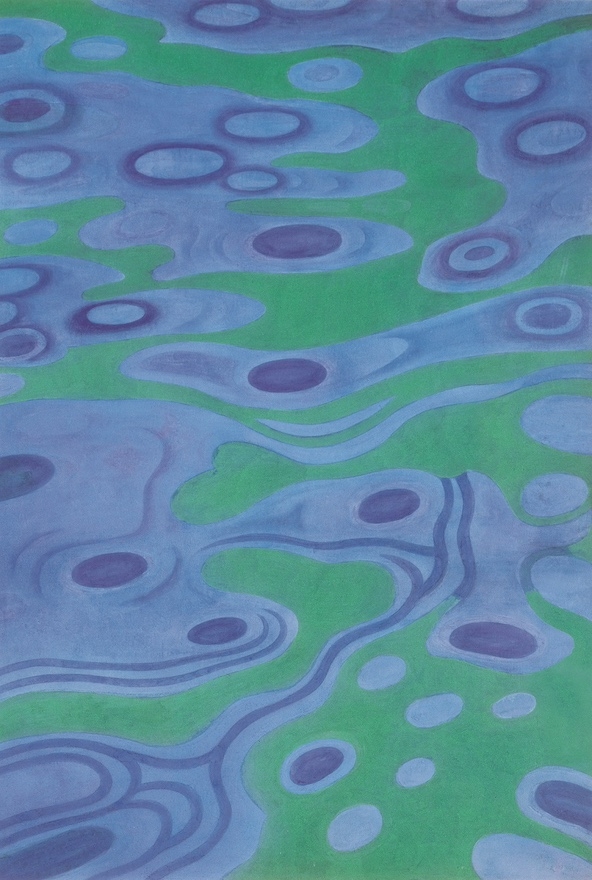

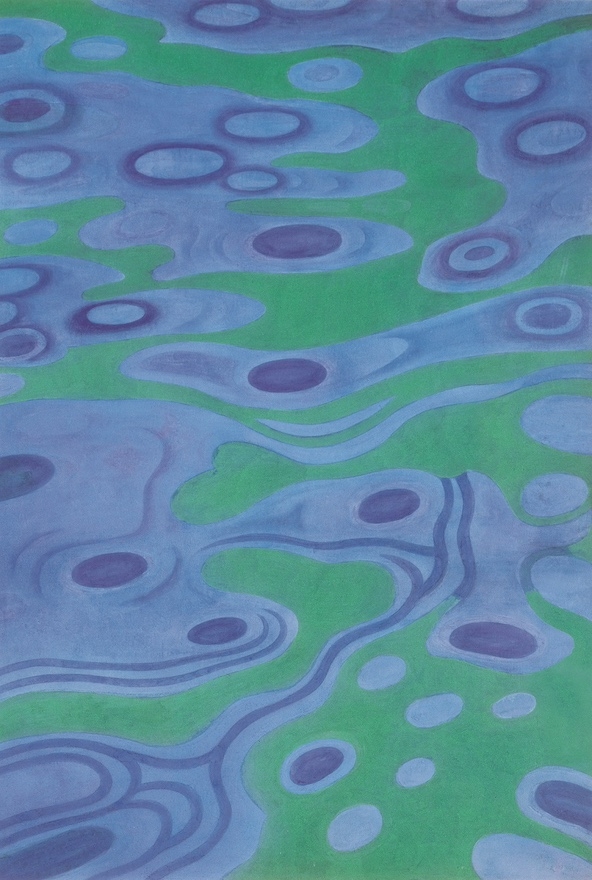

Summer Pond (c. 1922, Nikaido Museum of Art), the surface of the water is depicted using the leaves of water lilies, while in works from Heihachiro’s later years (

Spring Rain, 1964;

Water, 1958), there is the expression of water using Monet-like approaches from both sides.

2

Carp (1921)

Reflection and ripples expressing water from both sides: Spring Rain (1964, Rantokaku Art Museum)

Different color fields and ripples expressing water from both sides: Water (1958, Oita Prefectural Art Museum)

Throughout his life, Heihachiro moved back and forth between treating water as a medium and treating it as a surface. He was at his most original on the former occasions. Let us look at

Globefish and Flounder (c. 1924). Here, instead of the shadows of carp indicating the bottom of the pond, the same thing is expressed with a flounder on its side at the bottom of the sea, with the seabed directly connected to the space in the water in which the globefish swim. In

Red Carp (1930), the rain falling on the pond and the red carp in the water are painted in a continuum (the ripples on the surface of the water are also depicted, but they are too faint to constitute the surface itself).

Globefish and Flounder (c. 1924, Oita Prefectural Art Museum)

Red Carp (1930, The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto)

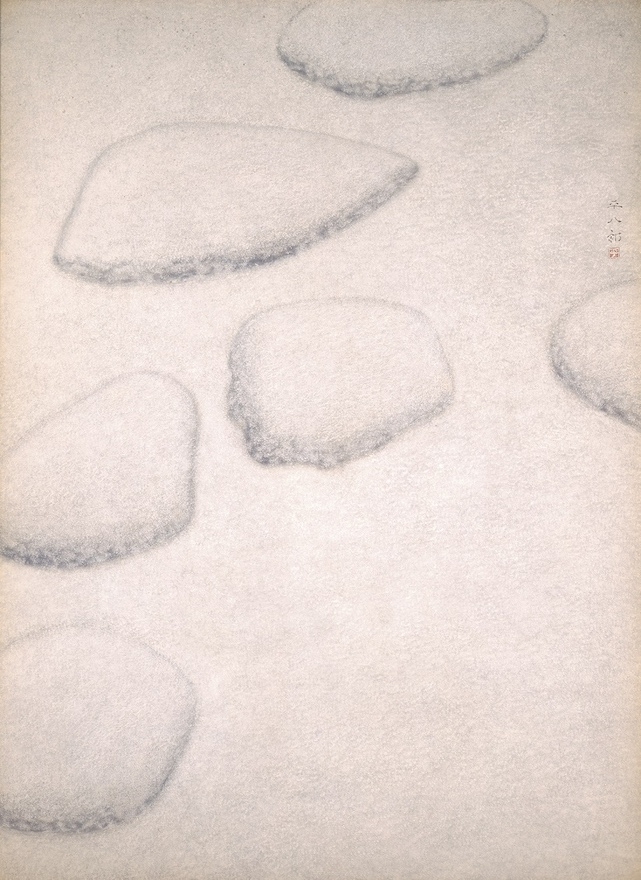

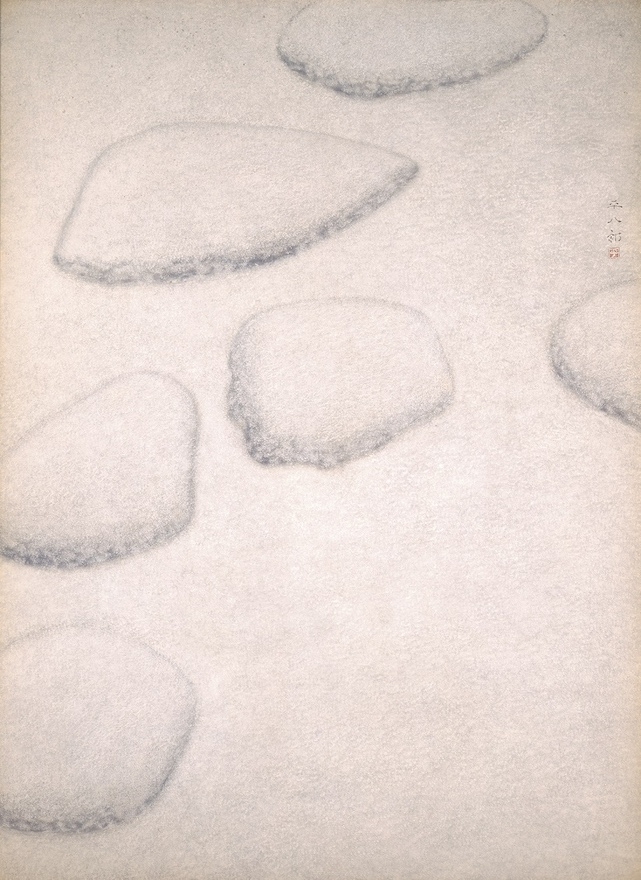

The bipolarity running through all of Heihachiro’s painting consisting of the medium filling his painterly space (“water”) and the surface of that medium (the “water’s surface”) also appears as snow covering the surface of the world (numerous examples, including

Fresh Snow, c. 1935;

Snowy Garden, 1936;

Fresh Snow, 1948;

Garden Stones after Slightly Snowing, 1958;

Spring Snow, 1949; and

Snowy Garden, 1964), while the relationship between carp and water and between sweetfish and water also appears in the form of birds and air (

Bulbul, 1939;

Pigeons, 1940), and more generally as flowers/birds and air in Heihachiro’s paintings of flowers and birds, and is also developed as clouds and air (

Cloud, 1950).

Fresh Snow (1948, Oita Prefectural Art Museum)

Cloud (1950, Oita Prefectural Art Museum)

Occasionally, due to not painting the water (the medium), Heihachiro concentrated his expression on surfaces alone. In

Ice (1955), surface and medium combine as one due to freezing and become volume, while in

Rain (1953), he expresses the rain that fills the atmosphere through marks left by rain that has begun to dampen the surfaces of dry rooftiles.

Ice (1955)

Rain (1953, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo)

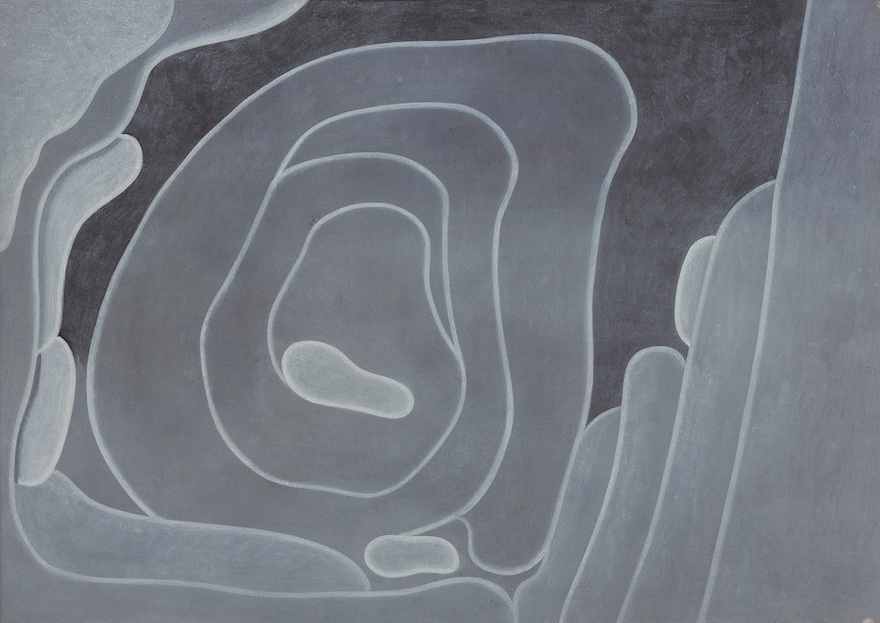

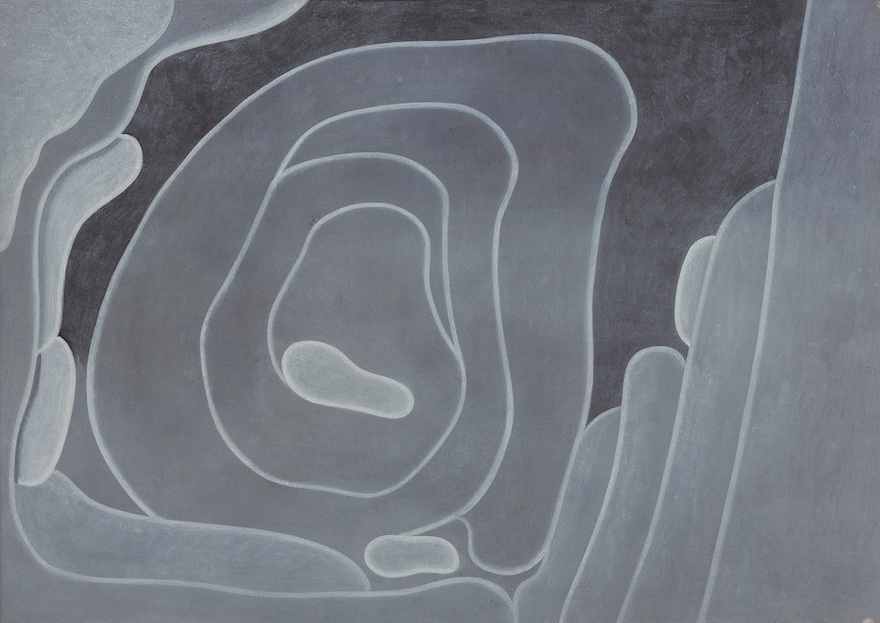

The famous work

Ripples (1932) is probably an extension of this. This work is based on a photograph of the surface of water taken by a photographer, but Heihachiro’s aim is above all to express not the surface of the water (a layer), but the trembling of the water (the medium) by depicting the pattern on the top layer created by the wind causing the surface of the water to wrinkle. Although small in number, there are also works in which the two poles appear simultaneously. Examples of this include

Sweetfish (1935) and

Sweetfish (1940, Oita Art Museum), in which fish and surfaces of water merge.

Ripples (1932, Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka)

The difference between the methods employed by the two painters Heihachiro and Monet lies in the divergence of their aims. Heihachiro’s “water” is not the “surface of the water (a layer)” of Monet, but water as a medium encompassing carp and sweetfish. It is not a transparent basal layer supporting all visible images, but a transparent volume that fills the middle of pictures as a result of painting fish. If Monet’s “water surfaces” were the essence of Western painting, then we can probably say that Heihachiro’s “water” is the essence of

shasei (literally, “depiction of life”) in nihonga.

Monet developed his water lilies while matching invisible, nonmaterial layers against the materiality of his materials (supports, paint) (whether layers would emerge or not regardless of how stickily he painted with oil and even if he showed the unpainted surfaces of his supports). In his later years (from the 1960s onwards), perhaps influenced by Kumagai Morikazu (1880–1977), Heihachiro simplified his “water” as a medium, which is to say his “depictive” expression, in the direction of decorativeness/abstraction. With this, however, his “water,” the point of which was supposedly not to paint it, turned into vague color field formations, and his picture planes overall, far from being filled with transparent mediums, became completely flat.

——————————–

1. “‘Koi’ ga mizu o hanareru made” [Until the “carp” leaves the water], Binokuni 11, no. 8 (August 1935). Reprinted in the catalogue to this exhibition, p. 222.

2. However, unlike Monet’s Water Lilies, because the “ripples” represent the movement of the medium (water), it is clear that what Heihachiro is consistently aiming for is not “the surface” but “the volume of the medium.”

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University.

Fukuda Heihachiro: A Retrospective was held at the

Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka, from March 9 to May 6, 2024.

The exhibition has traveled to the

Oita Prefectural Art Museum, and is being held through July 15.