Cultural Currency 25: Kimura Hideki: Celadon, Water Bird @ imura art gallery

Translucency, another kind of water

By Shimizu Minoru

2024.06.28

Courtesy the artist and imura art gallery (all photos)

Last time, I pointed out how one can see throughout the work of Fukuda Heihachiro a bipolarity consisting of “water as a medium” and “the water’s surface as a layer.” If we reframe this as a conflict between “non-layer-like things” and “layers,” then it is clear that the work of Kimura Hideki, too, is created between these two poles, and in such a way that each cancels out the other.

In looking back over Kimura Hideki’s career, we should probably touch on Maxi Graphica. Founded by Kimura and active from 1988 to 2008, Maxi Graphica was a movement that reinterpreted silkscreen printing as a multilayered medium that was both painting and photography, and explored its possibilities while relating the inescapably layer-like act of repeatedly printing an image using plates to the materiality of supports and ink (non-layer-like elements), and in so doing expanded printerly expression to a maximum and freed it from the yoke of technical artistry.1 Its mode of expression involved developing—after an interval of time, in the medium of silkscreen printing—subjects such as layering, collage, materiality, and transparency that emerged in the early 20th century. “Indirectness, layer-building, a fragmented production process, the equivalence of photographic images and handwork, imaging by way of transference/juxtaposition/inversion/repetition.”2 All of Kimura’s series can be considered as examples of this kind of collaging of layers.

At the same time, Kimura’s debut work took as its theme “life-size” in the medium of photography. As long as they are media—things mediating between other things—all media possess resistance as “things.” The hands and eyes of the artist overcome this resistance by assimilating the various media, giving rise to free expression, but this is simply a case of the person using them become familiar with them, and each medium always incorporates a singularity that eludes this acclimation by a person’s eyes or hands, and undermines the illusion of “freedom.” This is where media regain their otherness as “things,” triggering a peculiar giddiness.

For photography, “life-size” was such a giddiness. Since the age of the camera obscura, photography has become familiar to everybody as a medium that fixes projected images on planes photochemically. Essentially, images projected onto planes lack the dimension of size. Given this, by inserting a dimension that ought to be absent, “life-size” completely nullifies the principle of projection. As a result of the rendering of the object and its image as equivalent, photographs cease to be mere layers and regain the original giddiness of photography in which the same, single entity is multiplied into equivalent doubles.3

Viewed this way, even if Kimura’s art is the collaging of layers, we can perhaps conclude that its essence in fact lies in the imagining of space between front and back surfaces by resisting the reduction of things to pure planes and creating gaps and filling these with air (Fukuda Heihachiro’s “water”) (New Fall, the Mondrian series, etc.), painting on both sides of sheets of glass (the glass paintings) or making holes in paper that has been printed on both sides (the Charcoal series). In other words, Kimura’s genius lies in his suspending the layer-like essence of the mediums of photoengraving and silkscreen printing by means of the non-layer-like singularity (“life-size”) of the mediums themselves. I seem to recall that, befitting Kimura’s works that are neither transparent layers nor opaque non-layers, his large-scale retrospective (1999, Kyoto City Museum of Art) was titled “Translucency.”

At the same time, Kimura’s debut work took as its theme “life-size” in the medium of photography. As long as they are media—things mediating between other things—all media possess resistance as “things.” The hands and eyes of the artist overcome this resistance by assimilating the various media, giving rise to free expression, but this is simply a case of the person using them become familiar with them, and each medium always incorporates a singularity that eludes this acclimation by a person’s eyes or hands, and undermines the illusion of “freedom.” This is where media regain their otherness as “things,” triggering a peculiar giddiness.

For photography, “life-size” was such a giddiness. Since the age of the camera obscura, photography has become familiar to everybody as a medium that fixes projected images on planes photochemically. Essentially, images projected onto planes lack the dimension of size. Given this, by inserting a dimension that ought to be absent, “life-size” completely nullifies the principle of projection. As a result of the rendering of the object and its image as equivalent, photographs cease to be mere layers and regain the original giddiness of photography in which the same, single entity is multiplied into equivalent doubles.3

Viewed this way, even if Kimura’s art is the collaging of layers, we can perhaps conclude that its essence in fact lies in the imagining of space between front and back surfaces by resisting the reduction of things to pure planes and creating gaps and filling these with air (Fukuda Heihachiro’s “water”) (New Fall, the Mondrian series, etc.), painting on both sides of sheets of glass (the glass paintings) or making holes in paper that has been printed on both sides (the Charcoal series). In other words, Kimura’s genius lies in his suspending the layer-like essence of the mediums of photoengraving and silkscreen printing by means of the non-layer-like singularity (“life-size”) of the mediums themselves. I seem to recall that, befitting Kimura’s works that are neither transparent layers nor opaque non-layers, his large-scale retrospective (1999, Kyoto City Museum of Art) was titled “Translucency.”

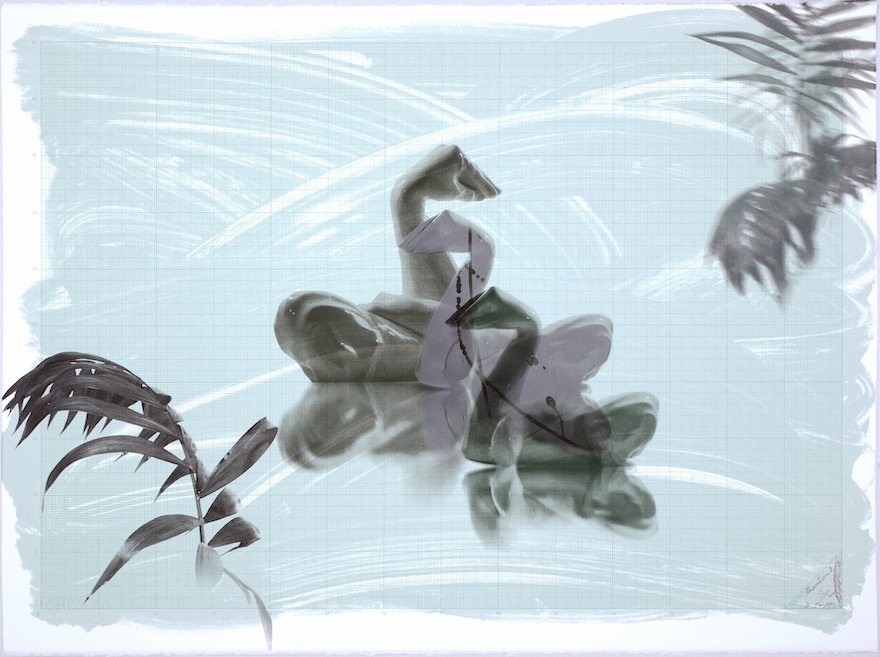

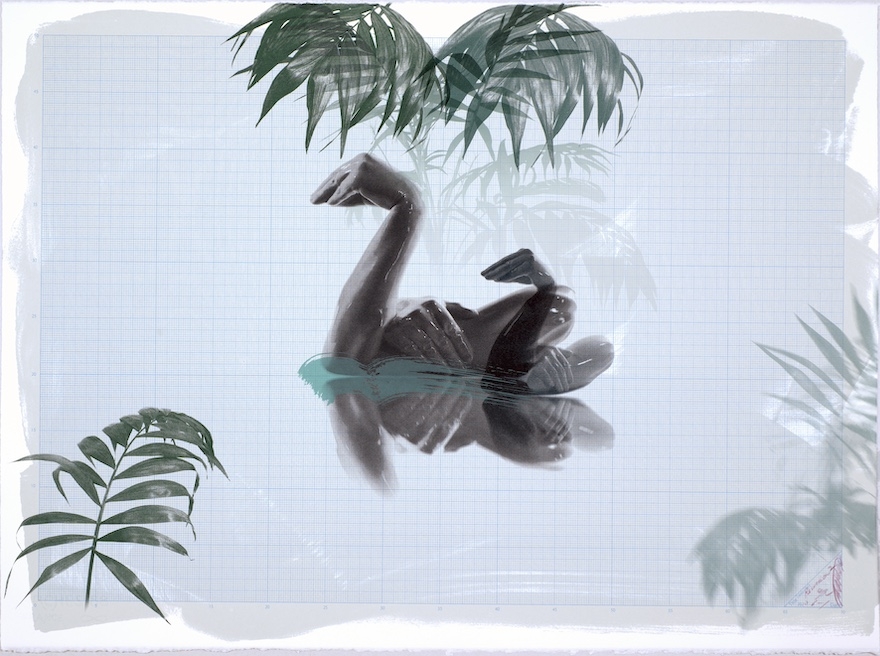

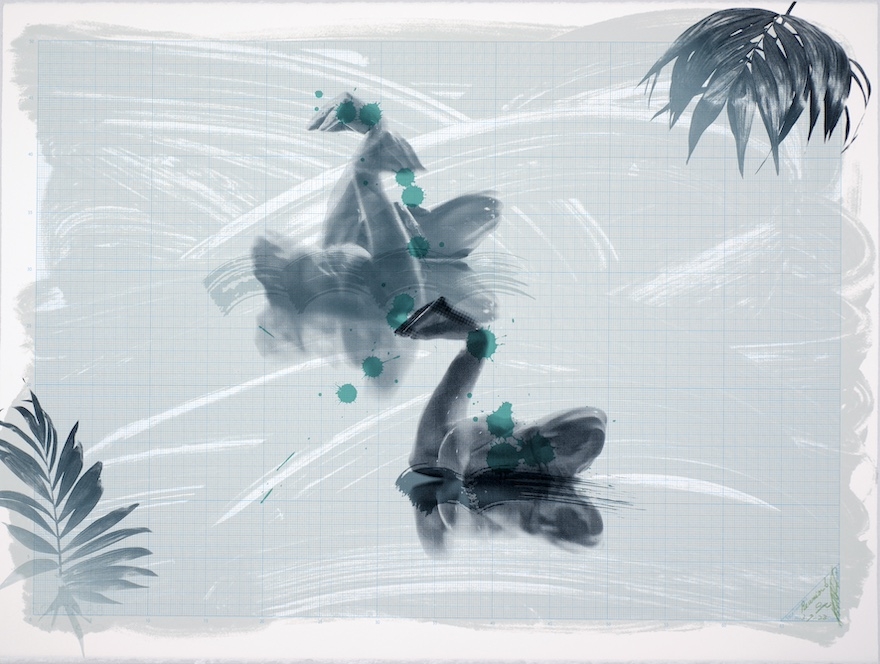

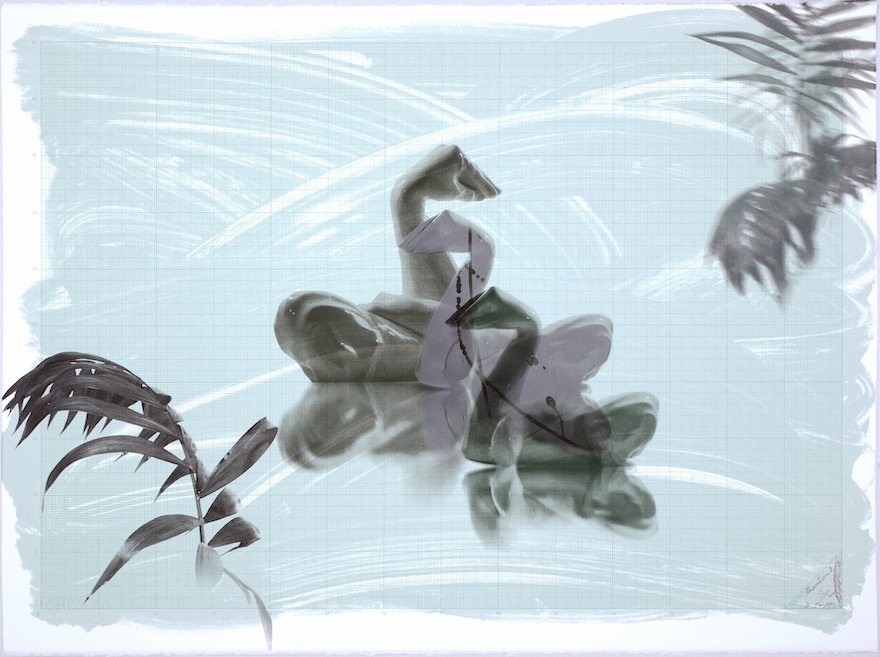

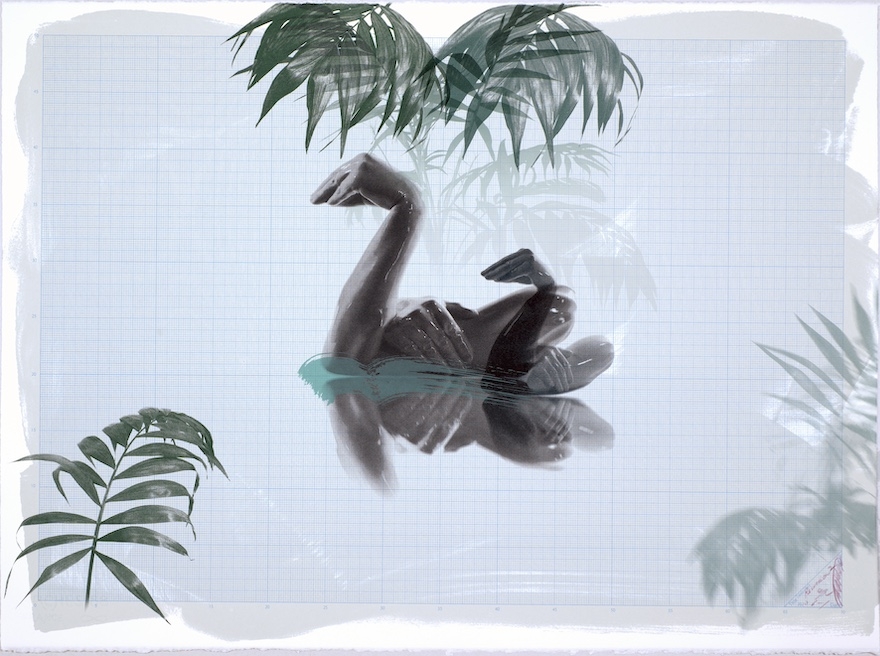

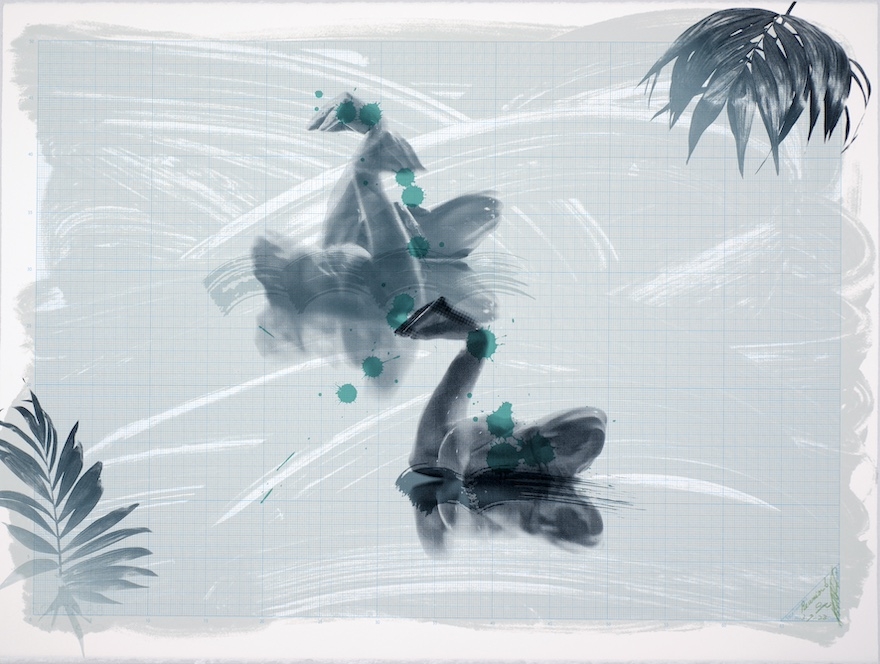

Translucency is also a key to interpreting this exhibition. There is a centerpiece—an object formed from beautiful celadon porcelain depicting a waterbird floating on water (a motif of arm and hands combined to cast a shadow image in the shape of a waterbird)—surrounded by a number of silkscreen works consisting of waterbird motifs over which various layers have been applied. In developing these exquisite variations of photoengraving, the artist is like a fish that has found water. He has printed a series of non-layer-like elements (white brushmarks; fragments of leafy plants and waterbird motifs given a sense of perspective through variation in size, focus, shade of color, and arrangement) over layer-like elements (graph paper), and even added layers (mirror surfaces and water surfaces that intersect at right angles with the picture plane) arising from the symmetry of the motifs (mirror images, reflections in water). The restrained color tones gave me a renewed appreciation of the fine sense of the artist.

Translucency is also a key to interpreting this exhibition. There is a centerpiece—an object formed from beautiful celadon porcelain depicting a waterbird floating on water (a motif of arm and hands combined to cast a shadow image in the shape of a waterbird)—surrounded by a number of silkscreen works consisting of waterbird motifs over which various layers have been applied. In developing these exquisite variations of photoengraving, the artist is like a fish that has found water. He has printed a series of non-layer-like elements (white brushmarks; fragments of leafy plants and waterbird motifs given a sense of perspective through variation in size, focus, shade of color, and arrangement) over layer-like elements (graph paper), and even added layers (mirror surfaces and water surfaces that intersect at right angles with the picture plane) arising from the symmetry of the motifs (mirror images, reflections in water). The restrained color tones gave me a renewed appreciation of the fine sense of the artist.

For all that, the centerpiece was after all the celadon object, because it amply demonstrates the essence of Kimura’s art, which is the layering of the conflict between layered-ness (A) and non-layered-ness (B), and the filling of works in their entirety with translucent media (Kimura Hideki’s “water”). Firstly, starting with the waterbird that is the motif, there is the sculpture (= B) that forms the basis of the shadow image (the origins of photography and painting in the form of skiagraphia = A). The celadon tiles created from molds made with a 3D printer and on which two kinds of ripples appear (small ripples that spread across the water’s surface and a single set of large ripples centered on the water bird) at once create the illusion of the surface of water on account of the ripples (= A) and exist as tiles that are literally “wavy” (= B). Moreover, the whole of the object (= B) is reflected in a mirror surface (= A), imitating the surrounding print works.

For all that, the centerpiece was after all the celadon object, because it amply demonstrates the essence of Kimura’s art, which is the layering of the conflict between layered-ness (A) and non-layered-ness (B), and the filling of works in their entirety with translucent media (Kimura Hideki’s “water”). Firstly, starting with the waterbird that is the motif, there is the sculpture (= B) that forms the basis of the shadow image (the origins of photography and painting in the form of skiagraphia = A). The celadon tiles created from molds made with a 3D printer and on which two kinds of ripples appear (small ripples that spread across the water’s surface and a single set of large ripples centered on the water bird) at once create the illusion of the surface of water on account of the ripples (= A) and exist as tiles that are literally “wavy” (= B). Moreover, the whole of the object (= B) is reflected in a mirror surface (= A), imitating the surrounding print works.

The celadon used is of a color reminiscent of the Longquan kilns during their golden age. If the beauty of the West was the beauty of transparency as exemplified in glass and jewels, then the beauty of the East was based on the translucent beauty whose ideal is jade (after the rise of the global empire that was the Yuan dynasty, this aesthetic gave way to the beauty of transparency in the form of blue and white porcelain). The color of celadon originally had as its ideal the beauty of jade and was created by pouring a glaze over pottery clay (= A) and relying on the reaction between the glaze and the clay inside the kiln (= B). Light passes through the layers of glaze that contain tiny air bubbles—in other words, that is slightly cloudy—and is repelled by the clay and escapes while being reflected diffusely by the air bubbles, a process that gives rise to the subtle color that can be called neither blue nor green. The beauty of celadon is the beauty of translucency.

——————————–

The celadon used is of a color reminiscent of the Longquan kilns during their golden age. If the beauty of the West was the beauty of transparency as exemplified in glass and jewels, then the beauty of the East was based on the translucent beauty whose ideal is jade (after the rise of the global empire that was the Yuan dynasty, this aesthetic gave way to the beauty of transparency in the form of blue and white porcelain). The color of celadon originally had as its ideal the beauty of jade and was created by pouring a glaze over pottery clay (= A) and relying on the reaction between the glaze and the clay inside the kiln (= B). Light passes through the layers of glaze that contain tiny air bubbles—in other words, that is slightly cloudy—and is repelled by the clay and escapes while being reflected diffusely by the air bubbles, a process that gives rise to the subtle color that can be called neither blue nor green. The beauty of celadon is the beauty of translucency.

——————————–

1. See Kimura Hideki, Tanaka Takashi, Hamada Hiroaki et al., “Roundtable discussion: The ‘painting and print’ aims of Maxi Graphica,” part of “The future form of screen-printing” feature, Hanga Geijutsu 106 (1999): 90–97. 2. Kimura Hideki, “The mystery of Maxi Graphica printmaking,” in Kansai Prints 1950s–2000s (Bigaku Shuppan, 2007), 293. 3. The same concerns have been repeated in the Charcoal series of recent years. Charcoal was expressed as three-dimensional forms rising from two-dimensional surfaces by photographing it in life-size, printing these photographs using (ink mixed with) charcoal on both sides of sheets of paper and making holes in the paper. Here, a number of equivalences were at work (life-size, printing charcoal with charcoal, two-dimensional⇄three-dimensional, front⇄back), indicating the starting point of Kimura Hideki’s practice.

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University.

Kimura Hideki: Celadon, Water Bird was held at imura art gallery kyoto from May 8 to 25, 2024. Three prints from Kimura’s Pencil series are being displayed at the “Tectonic Shifts in Printing, Printmaking and Graphic Design 1957–1979” exhibition held at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, through August 25, 2024.

Celadon Lake

Reunion 1

Reunion 2

Reunion 6

Reunion 7

Installation view

1. See Kimura Hideki, Tanaka Takashi, Hamada Hiroaki et al., “Roundtable discussion: The ‘painting and print’ aims of Maxi Graphica,” part of “The future form of screen-printing” feature, Hanga Geijutsu 106 (1999): 90–97. 2. Kimura Hideki, “The mystery of Maxi Graphica printmaking,” in Kansai Prints 1950s–2000s (Bigaku Shuppan, 2007), 293. 3. The same concerns have been repeated in the Charcoal series of recent years. Charcoal was expressed as three-dimensional forms rising from two-dimensional surfaces by photographing it in life-size, printing these photographs using (ink mixed with) charcoal on both sides of sheets of paper and making holes in the paper. Here, a number of equivalences were at work (life-size, printing charcoal with charcoal, two-dimensional⇄three-dimensional, front⇄back), indicating the starting point of Kimura Hideki’s practice.

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University.

Kimura Hideki: Celadon, Water Bird was held at imura art gallery kyoto from May 8 to 25, 2024. Three prints from Kimura’s Pencil series are being displayed at the “Tectonic Shifts in Printing, Printmaking and Graphic Design 1957–1979” exhibition held at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, through August 25, 2024.