Cultural Currency 27: “Fukuoka Michio: The Quiet Avant-Garde” @ Sakai Plaza of Rikyu and Akiko

He could have had something to do

By Shimizu Minoru

2024.09.17

All photos of Fukuoka's work: Kano Shunsuke

I was unaware that Fukuoka Michio (1936–2023, from Sakai) had died at the end of last year. What is more, in accordance with his own wishes, his body was donated to science. May he rest in peace.

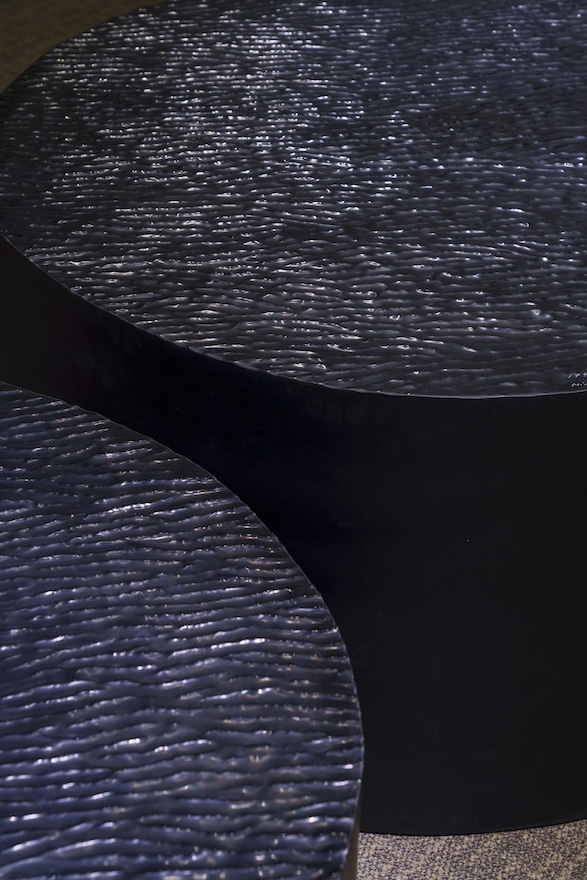

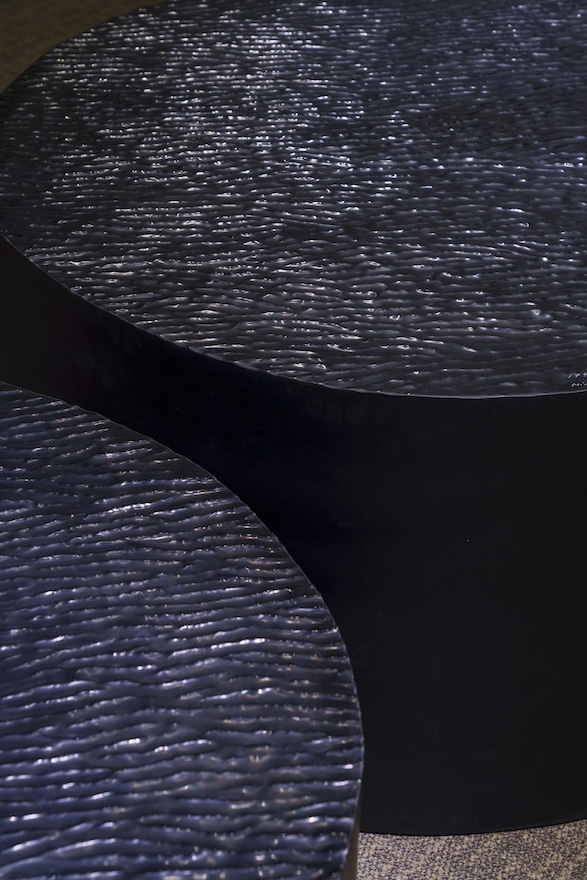

Fukuoka’s early works are characterized by groups of informal, unproductive, impotent objects made from waste materials left on the roadside (SAND 9) in which the phallocentric “creative subject” is thoroughly dismantled, and could be compared to the works of Kudo Tetsumi (1935–1990), who was more or less the same age as Fukuoka. However, what actually made Fukuoka unique were the representational works from the 1970s onwards, and as reference points for these one should probably cite not contemporary art but the likes of Tsuge Yoshiharu (b. 1937) and Mizuki Shigeru (1922–2015). There are similarities between the terrifyingly unpleasant and strangely realistic images tinged with masochistic humor that can be seen in the manga created by these artists and Fukuoka’s works that resemble balloon bombs (Black Balloons), his giant moths that “fall” like black rain and have an unpleasant black luster reminiscent of cockroaches, and his pitch-black water surfaces that spread out thinly on top of empty coffins (Masanda Pond, The Crucian Carp I Missed Was 45 cm.).

Fukuoka’s early works are characterized by groups of informal, unproductive, impotent objects made from waste materials left on the roadside (SAND 9) in which the phallocentric “creative subject” is thoroughly dismantled, and could be compared to the works of Kudo Tetsumi (1935–1990), who was more or less the same age as Fukuoka. However, what actually made Fukuoka unique were the representational works from the 1970s onwards, and as reference points for these one should probably cite not contemporary art but the likes of Tsuge Yoshiharu (b. 1937) and Mizuki Shigeru (1922–2015). There are similarities between the terrifyingly unpleasant and strangely realistic images tinged with masochistic humor that can be seen in the manga created by these artists and Fukuoka’s works that resemble balloon bombs (Black Balloons), his giant moths that “fall” like black rain and have an unpleasant black luster reminiscent of cockroaches, and his pitch-black water surfaces that spread out thinly on top of empty coffins (Masanda Pond, The Crucian Carp I Missed Was 45 cm.).

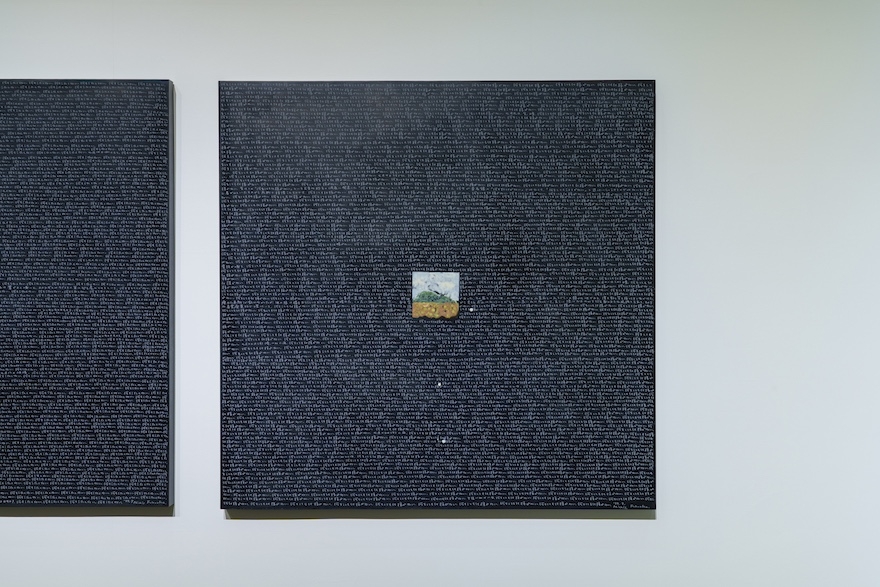

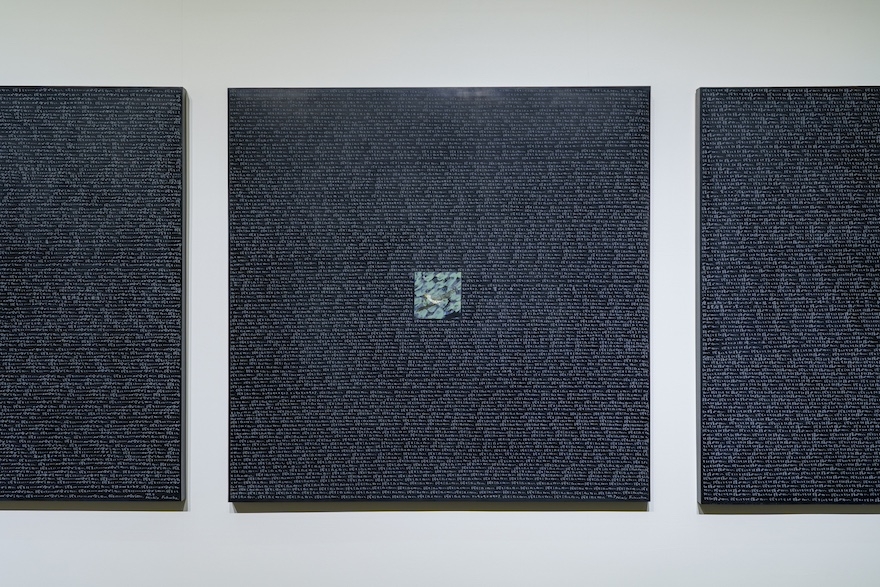

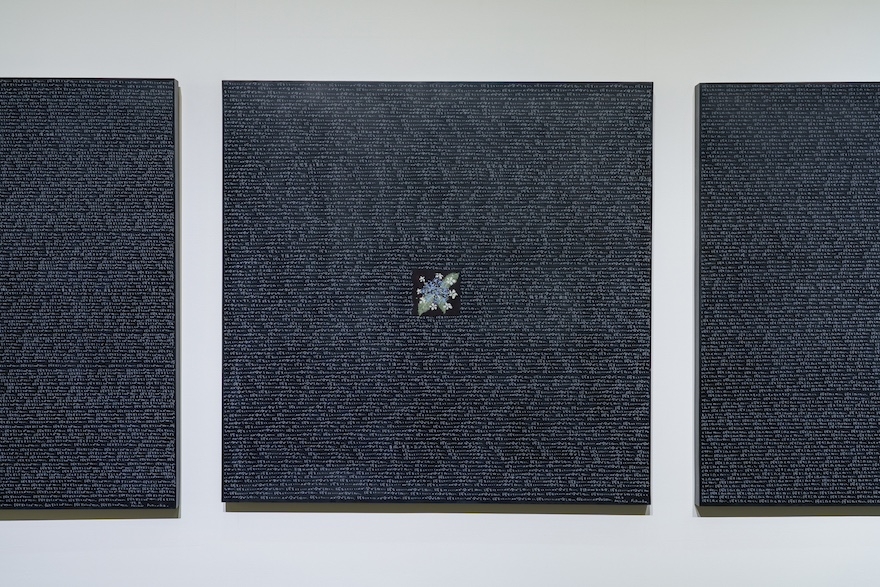

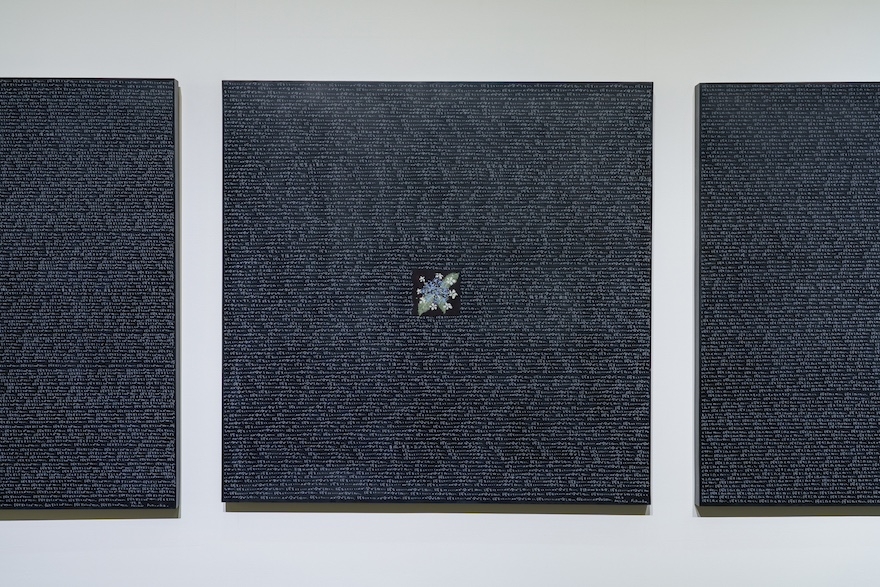

Backing up the series Fukuoka produced from 1998 onwards, including “It Doesn’t Matter What I Do,” “I Don’t Feel Like Doing Anything,” “I Don’t Know What to Do,” and “I Don’t Have Anything to Do,” was the reality of being alive in post-war Japan when time stood still under the rule of the US military without being conscious of this, or in other words of being oppressed (“Should we really not be scared?”), and the realization that Japanese contemporary art exists on the basis of the denial of this complete cultural emasculation. This denial of emasculation means behaving as a Japanese towards the US (emasculation) and as an American towards Japan (the denial of emasculation), and is a typical example of a colonized mentality. Fukuoka’s art involved fervently voicing “opposition” (the “Anti” stones) to this denial. It is probably appropriate that his final public works were the “Shriveled-up Balls” (2005) of oppressed men and the even smaller “Seeds” (2012). This problem that seized Fukuoka and would not let him go was not understood for a long time because it was concerned with Japanese contemporary art’s unconscious, so to speak. It was only after the advent of Neo-Pop that Japanese contemporary art came to objectify and concern itself strategically with this oppression. In other words, Fukuoka was the only artist of his generation to anticipate the likes of Neo-Pop and Showa 40-nen kai (The Group 1965).

Backing up the series Fukuoka produced from 1998 onwards, including “It Doesn’t Matter What I Do,” “I Don’t Feel Like Doing Anything,” “I Don’t Know What to Do,” and “I Don’t Have Anything to Do,” was the reality of being alive in post-war Japan when time stood still under the rule of the US military without being conscious of this, or in other words of being oppressed (“Should we really not be scared?”), and the realization that Japanese contemporary art exists on the basis of the denial of this complete cultural emasculation. This denial of emasculation means behaving as a Japanese towards the US (emasculation) and as an American towards Japan (the denial of emasculation), and is a typical example of a colonized mentality. Fukuoka’s art involved fervently voicing “opposition” (the “Anti” stones) to this denial. It is probably appropriate that his final public works were the “Shriveled-up Balls” (2005) of oppressed men and the even smaller “Seeds” (2012). This problem that seized Fukuoka and would not let him go was not understood for a long time because it was concerned with Japanese contemporary art’s unconscious, so to speak. It was only after the advent of Neo-Pop that Japanese contemporary art came to objectify and concern itself strategically with this oppression. In other words, Fukuoka was the only artist of his generation to anticipate the likes of Neo-Pop and Showa 40-nen kai (The Group 1965).

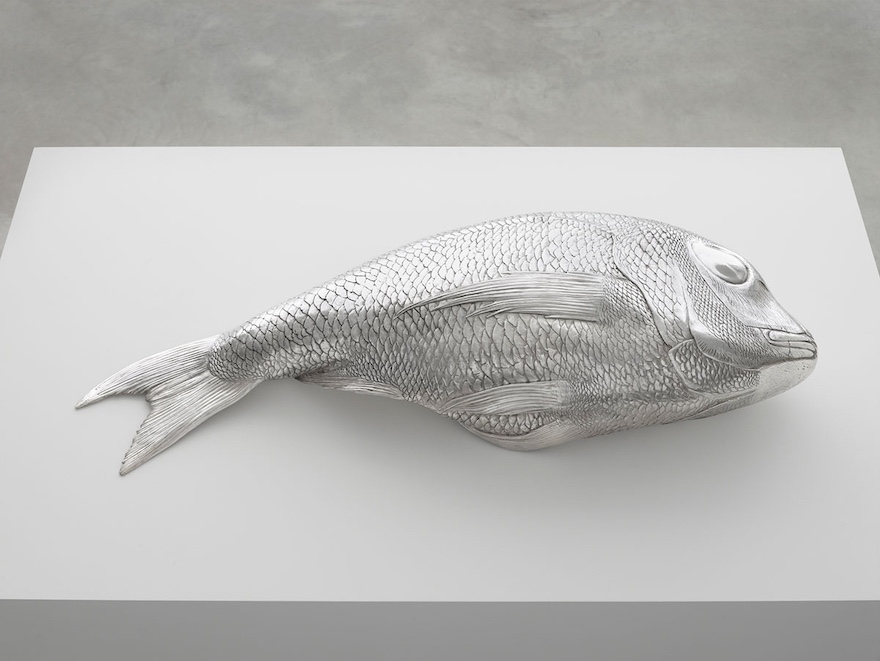

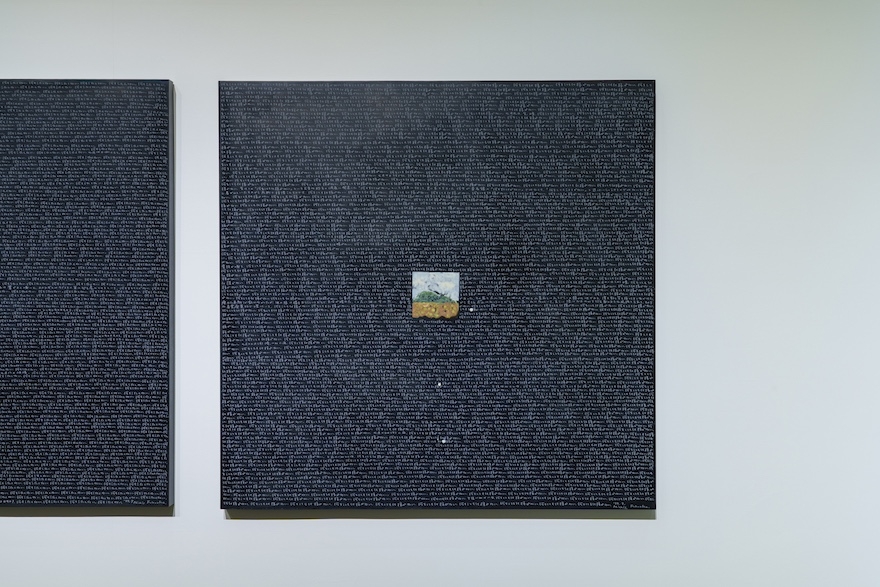

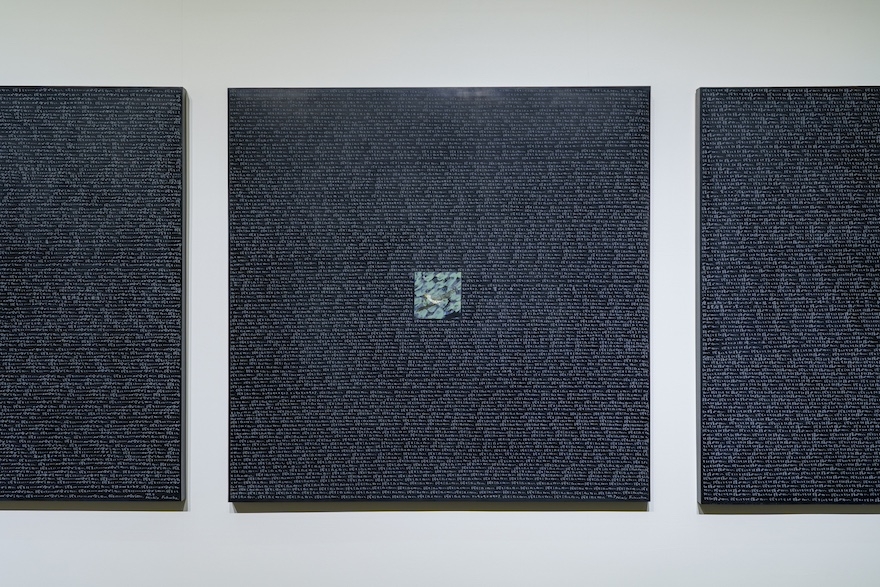

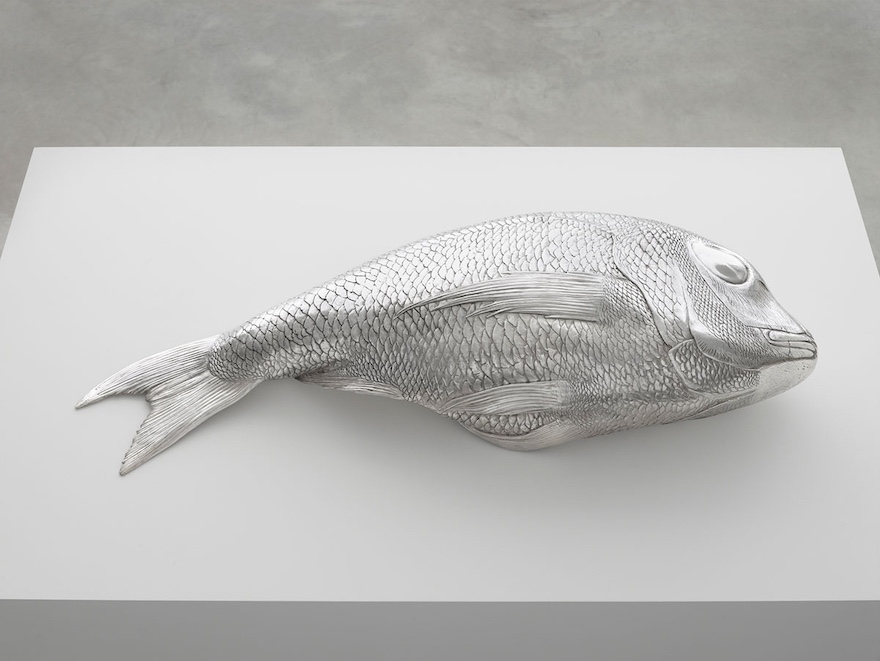

The castrated ”Balls” and the “Earthworms” series (Angry Earthworm, Laughing Earthworms) were acknowledgements of this emasculation, while “Seeds” were the first works produced with it as a starting point. Worked out from his fingertips, “Seeds” are the absolute minimum in terms of sculpture, representing sculpture in which the “visual sense” as a symbol of the phallic subject has been abandoned. These works not only follow in the tradition of “anti-” art, but transcend the locality of Japan to arrive at the extremely interesting genre of “anti-” visual representative sculpture, a genre for which there are few precedents in Japan. They also represent art in which masochism and vulnerability exceed a certain upper limit and become humor tinged with insanity. If pressed to make a comparison, one could perhaps cite several works by Charles Ray (b. 1953). Fukuoka’s cheap materials (FRP!) and finishing that retains a handmade feeling (handwritten text!) and Ray’s gorgeous materials (sterling silver!) and flawless finishing entrusted to factories and craftsmanship correspond because they are at opposite ends of the spectrum.

The castrated ”Balls” and the “Earthworms” series (Angry Earthworm, Laughing Earthworms) were acknowledgements of this emasculation, while “Seeds” were the first works produced with it as a starting point. Worked out from his fingertips, “Seeds” are the absolute minimum in terms of sculpture, representing sculpture in which the “visual sense” as a symbol of the phallic subject has been abandoned. These works not only follow in the tradition of “anti-” art, but transcend the locality of Japan to arrive at the extremely interesting genre of “anti-” visual representative sculpture, a genre for which there are few precedents in Japan. They also represent art in which masochism and vulnerability exceed a certain upper limit and become humor tinged with insanity. If pressed to make a comparison, one could perhaps cite several works by Charles Ray (b. 1953). Fukuoka’s cheap materials (FRP!) and finishing that retains a handmade feeling (handwritten text!) and Ray’s gorgeous materials (sterling silver!) and flawless finishing entrusted to factories and craftsmanship correspond because they are at opposite ends of the spectrum.

Take, for example, the famous work Family Romance (1993). Four figures representing a father, mother, infant son and infant daughter, all naked and the same height, stand holding hands. Given that the pre-pubescent son and daughter are already as tall as the parents, it appears these parents are not blood relatives, as the real parents would be “larger” (Freud’s “The Family Romances”). Nothing could more thoroughly express the feelings of fear, self-abasement and uncanniness parents harbor at the bottom of their hearts towards their children in violation of society’s command to “love thy child.”

Take, for example, the famous work Family Romance (1993). Four figures representing a father, mother, infant son and infant daughter, all naked and the same height, stand holding hands. Given that the pre-pubescent son and daughter are already as tall as the parents, it appears these parents are not blood relatives, as the real parents would be “larger” (Freud’s “The Family Romances”). Nothing could more thoroughly express the feelings of fear, self-abasement and uncanniness parents harbor at the bottom of their hearts towards their children in violation of society’s command to “love thy child.”

Or take the more recent work, Fish (2011). The fish is a symbol of Christianity (the Greek word for fish, ichthys, is an acrostic for “Iesous Christos, Theou Yios, Soter,” or “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior”), while the presence of the sea bream (?) lying on its side on a chopping board is so vivid it almost makes one laugh. Moreover, because it is probably a cast-metal object made by creating a mold and pouring sterling silver into it (i.e. not hollow inside), it is probably quite heavy. In addition, “sterling silver” was originally the name of a type of coin used in England. In other words, the work is a symbol of the Savior made by recasting coins, and is so heavy it would be impossible to raise up.

Or take the more recent work, Fish (2011). The fish is a symbol of Christianity (the Greek word for fish, ichthys, is an acrostic for “Iesous Christos, Theou Yios, Soter,” or “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior”), while the presence of the sea bream (?) lying on its side on a chopping board is so vivid it almost makes one laugh. Moreover, because it is probably a cast-metal object made by creating a mold and pouring sterling silver into it (i.e. not hollow inside), it is probably quite heavy. In addition, “sterling silver” was originally the name of a type of coin used in England. In other words, the work is a symbol of the Savior made by recasting coins, and is so heavy it would be impossible to raise up.

1. Entrepot’s After School: The Work of Fukuoka Michio and Imamura Gen—From the 1950s to the 2000s, abridged edition, recorded 2004 / edited 2024.

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University.

“Fukuoka Michio: The Quiet Avant-Garde” was held at Sakai Plaza of Rikyu and Akiko from July 6 to September 1, 2024.

*

In 2005 he announced that he was “a sculptor who no longer sculpts,” and in fact he gave up sculpting in 2012 after producing “Seeds,” but his 60-year career was thoroughly traced in a major retrospective staged at the National Museum of Art, Osaka, in 2017. This show was a small memorial exhibition, as it were, which, as well as looking back on his practice through 12 works spanning the period from when he set out to become a sculptor to his final years, also presented for the first time rare video of a talk (a conversation with Imamura Hajime) recorded in the artist’s lifetime.1

SAND9, 1957

Black Balloons, 2002

Masanda Pond, 1991

Masanda Pond (detail), 1991

The Crucian Carp I Missed Was 45 cm., 1987

It Doesn’t Matter What I Do: July (Behind the Hill), 1999

I Don’t Feel Like Doing Anything: July (Lesser Cuckoo), 1999

I Don’t Know What to Do: July (Lacecap Hydrangea), 1999

I Don’t Have Anything to Do: July (KUSAMA), 1999

Opposition, 1996

Laughing Earthworms (two pieces at the left), 2005, and Angry Earthworm, 2005

Charles Ray, Family Romance, 1993, The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Charles Ray, Fish, 2011

*

However, comparing them like this shows how the humor of Fukuoka, who was after all himself a slave to “postwar Japan,” in the end tends towards social isolation. “Earthworms” and “Seeds” were all too clearly the final works in the life of the artist. There was no time or energy left in Fukuoka Michio to reinterpret them as the first steps in a new artistic journey. Ah, may he rest in peace.

Installation view

1. Entrepot’s After School: The Work of Fukuoka Michio and Imamura Gen—From the 1950s to the 2000s, abridged edition, recorded 2004 / edited 2024.

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University.

“Fukuoka Michio: The Quiet Avant-Garde” was held at Sakai Plaza of Rikyu and Akiko from July 6 to September 1, 2024.