Cultural Currency 28: "Soda Hirotaka Exhibition: Nihongo no shoji" @ Kita Modern Art Museum

NI本GOWO巡RU政治 (The politics surrounding the Japanese language): The language art of Soda Hirotaka

By Shimizu Minoru

2024.10.07

In the 1950s, calligraphy and contemporary art brushed past each other as part of the international exchanges that were abstract calligraphy and abstract painting, but the impact of these “forms beautiful but illegible” lasted for a long time. I say this because the pre-1970 style—a style based on the beauty of black ink, which is to say the mannerisms of brushstrokes and the spread and splatter of ink, and on single-character calligraphy—that seems to have already been exhausted even if one looks over the work of a single artist, Morita Shiryu, can still be seen in a lot of “avant-garde calligraphy” and “modern calligraphy.” The movement that critically carries on this tradition and searches for and practices a new fusion of calligraphy and contemporary art in the 21st century is Art Shodo Contemporary (hereinafter ASC).

The contemporary art world paid attention once again to calligraphy after Inoue Yuichi became well known, was the subject of a major retrospective exhibition, and gained recognition on the international art market. As noted in Cultural Currency 20, Art Shodo (Art Shodo Contemporary’s original title) was originally formed around a number of artists from the Tensakukai (2004-), a group established to pay homage to Inoue Yuichi and dedicated to the “liberation of calligraphy.” Numerous contemporary calligraphers, including not only members of the Tensakukai but also others from Hidai Tenrai (who is now beginning to be re-evaluated) up to the present, have each developed their own “avant-garde calligraphy.” However, if we were to apply a post-Yuichi filter—stepping back from the “international exchanges” of calligraphy and abstract painting, the essence of calligraphy not being in the beauty of black ink or the beauty of painting—much of “avant-garde calligraphy” would not be included in the calligraphy of the future. Within ASC there exists a faction that believes calligraphy and contemporary art should realize not what Duchamp might have called a “retinal” fusion (a fusion involving apparent effects and beauty alone), but a conceptual fusion. This faction redefines calligraphy as art that takes language as its subject matter and expresses language, positioning it within the same current as Joseph Kosuth, Kawara On, Jenny Holzer, the conceptual art of Art & Language and language art. At the cutting edge of this tendency is Soda Hirotaka.

The contemporary art world paid attention once again to calligraphy after Inoue Yuichi became well known, was the subject of a major retrospective exhibition, and gained recognition on the international art market. As noted in Cultural Currency 20, Art Shodo (Art Shodo Contemporary’s original title) was originally formed around a number of artists from the Tensakukai (2004-), a group established to pay homage to Inoue Yuichi and dedicated to the “liberation of calligraphy.” Numerous contemporary calligraphers, including not only members of the Tensakukai but also others from Hidai Tenrai (who is now beginning to be re-evaluated) up to the present, have each developed their own “avant-garde calligraphy.” However, if we were to apply a post-Yuichi filter—stepping back from the “international exchanges” of calligraphy and abstract painting, the essence of calligraphy not being in the beauty of black ink or the beauty of painting—much of “avant-garde calligraphy” would not be included in the calligraphy of the future. Within ASC there exists a faction that believes calligraphy and contemporary art should realize not what Duchamp might have called a “retinal” fusion (a fusion involving apparent effects and beauty alone), but a conceptual fusion. This faction redefines calligraphy as art that takes language as its subject matter and expresses language, positioning it within the same current as Joseph Kosuth, Kawara On, Jenny Holzer, the conceptual art of Art & Language and language art. At the cutting edge of this tendency is Soda Hirotaka.

Of course, Japanese is no exception. Japanese is a simple language to speak, but its writing method is probably among the most complicated and inscrutable in the entire world. This is all the result of international power relations. The process whereby “Japanese” was created amid these power relations can broadly be divided into three periods.

Needless to say, the first was the ancient period when Japan initially imported large numbers of characters from China and, by way of man’yogana (Chinese characters used for their pronunciation), devised hiragana as “women’s writing” and katakana for transliterating classical Chinese text. This gave rise to one of the world’s few polyphonic writing systems in which a single character can have multiple readings.

Next was the Meiji period when Japan, under an Imperial family that felt threatened by the European powers and underwent Westernization, hastily formed a modern “nation state.” During this period, modern Japanese with its unity of written and spoken styles was created amid the mass importation and translation into Japanese of concepts originating from the West, such as seishin (spirit), kukan (space) and gainen (concept), using expressions originally derived from classical Chinese. Until this period, all official documents were written in classical Chinese. Even amid calls to “quit Asia and join Europe,” this worship of classical Chinese did not diminish. Both the Meiji Constitution (1889) and the Imperial Rescript on Education (1890) were written in kanji and katakana in a style similar to the Japanese translations of classical Chinese writing.

The third period was of course Japan’s defeat in the Second World War and the occupation, which led to the worship of the West, and in particular a servility to the US, in place of the worship of classical Chinese. As the worship of classical Chinese diminished, kanji in Japanese underwent a peculiar simplification that resulted in them being neither unsimplified nor simplified Chinese characters, and Japan broke away completely from the original Chinese-character cultural sphere. Amid the stupor in which the fire-ravaged country found itself, there were even those who demanded that Japan abandon Japanese and adopt French (not English!) as the national language (Shiga Naoya) or abolish kanji and instead write using the Latin script. Neither demand was realized, but today’s Japanese is the product of this “postwar” structure, in which the Imperial family’s position is guaranteed under the US-drafted constitution and society is subordinate to the US-Japan Security Treaty and the US-Japan Status of Forces Agreement. So even as of 2024, the “postwar” era has not ended

Of course, Japanese is no exception. Japanese is a simple language to speak, but its writing method is probably among the most complicated and inscrutable in the entire world. This is all the result of international power relations. The process whereby “Japanese” was created amid these power relations can broadly be divided into three periods.

Needless to say, the first was the ancient period when Japan initially imported large numbers of characters from China and, by way of man’yogana (Chinese characters used for their pronunciation), devised hiragana as “women’s writing” and katakana for transliterating classical Chinese text. This gave rise to one of the world’s few polyphonic writing systems in which a single character can have multiple readings.

Next was the Meiji period when Japan, under an Imperial family that felt threatened by the European powers and underwent Westernization, hastily formed a modern “nation state.” During this period, modern Japanese with its unity of written and spoken styles was created amid the mass importation and translation into Japanese of concepts originating from the West, such as seishin (spirit), kukan (space) and gainen (concept), using expressions originally derived from classical Chinese. Until this period, all official documents were written in classical Chinese. Even amid calls to “quit Asia and join Europe,” this worship of classical Chinese did not diminish. Both the Meiji Constitution (1889) and the Imperial Rescript on Education (1890) were written in kanji and katakana in a style similar to the Japanese translations of classical Chinese writing.

The third period was of course Japan’s defeat in the Second World War and the occupation, which led to the worship of the West, and in particular a servility to the US, in place of the worship of classical Chinese. As the worship of classical Chinese diminished, kanji in Japanese underwent a peculiar simplification that resulted in them being neither unsimplified nor simplified Chinese characters, and Japan broke away completely from the original Chinese-character cultural sphere. Amid the stupor in which the fire-ravaged country found itself, there were even those who demanded that Japan abandon Japanese and adopt French (not English!) as the national language (Shiga Naoya) or abolish kanji and instead write using the Latin script. Neither demand was realized, but today’s Japanese is the product of this “postwar” structure, in which the Imperial family’s position is guaranteed under the US-drafted constitution and society is subordinate to the US-Japan Security Treaty and the US-Japan Status of Forces Agreement. So even as of 2024, the “postwar” era has not ended

——————————–

——————————–

Soda Hirotaka (b. 1974; from Kyoto)

Graduated in fine arts (oil painting) from Kyoto Seika University. He began participating in Art Shodo in 2019, catching the attention of Shimizu Minoru, and has since participated in ASC exhibitions almost every year. In 2023, he exhibited at Art Shodo’s “Shodo New Age” exhibition, where he won the Shimizu Minoru Award.

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University

“Soda Hirotaka Exhibition: Nihongo no shoji” is being held at the Kita Modern Art Museum through December 1, 2024.

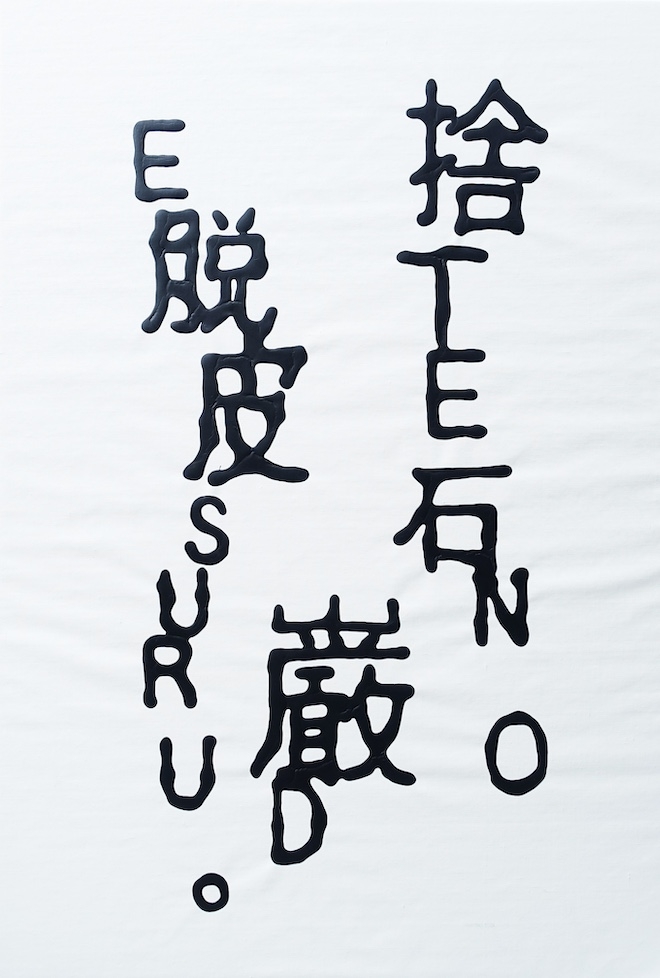

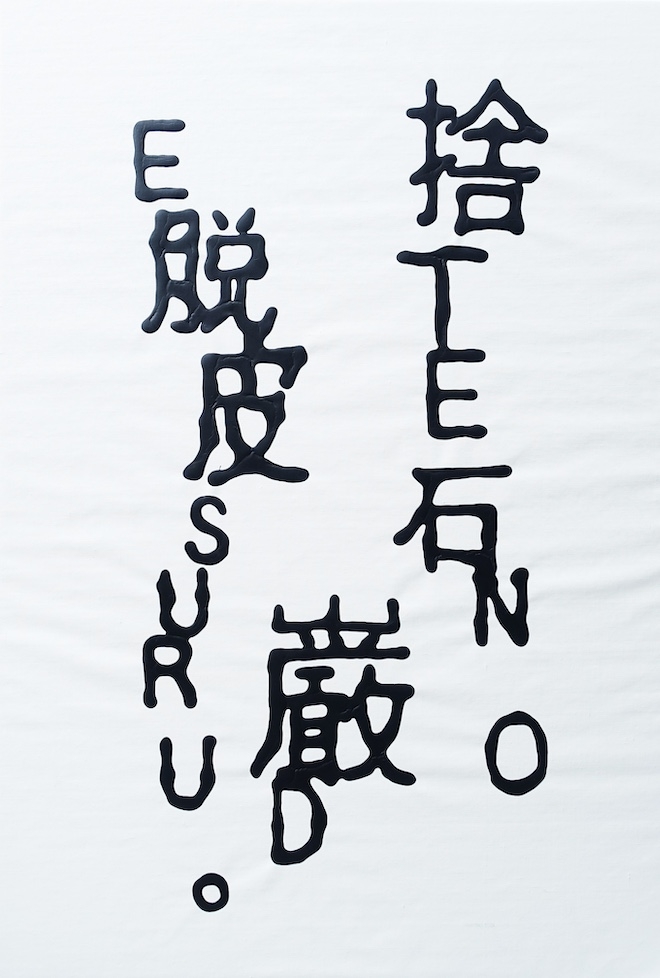

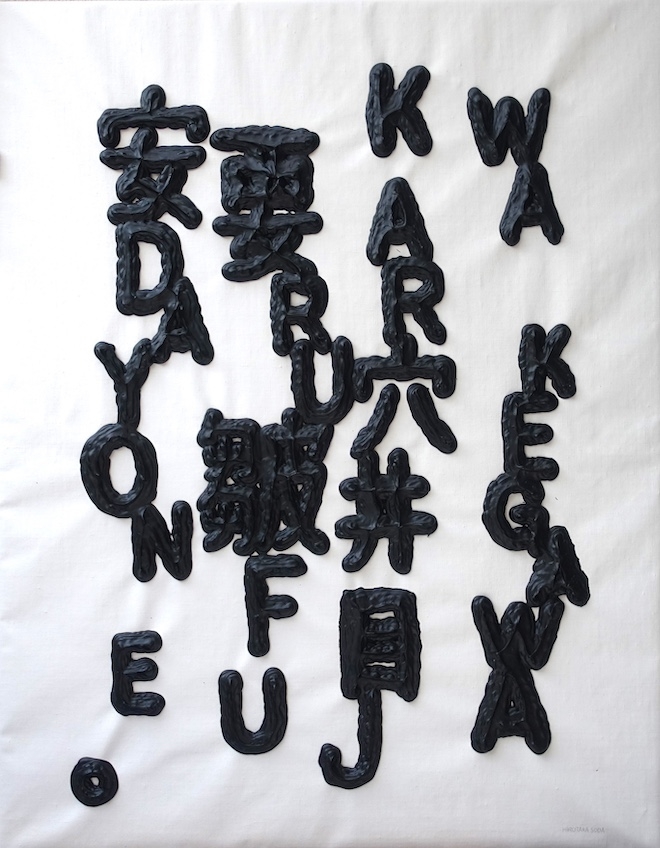

Suteishi no iwao de dappi suru., 2024, 162 × 112 cm

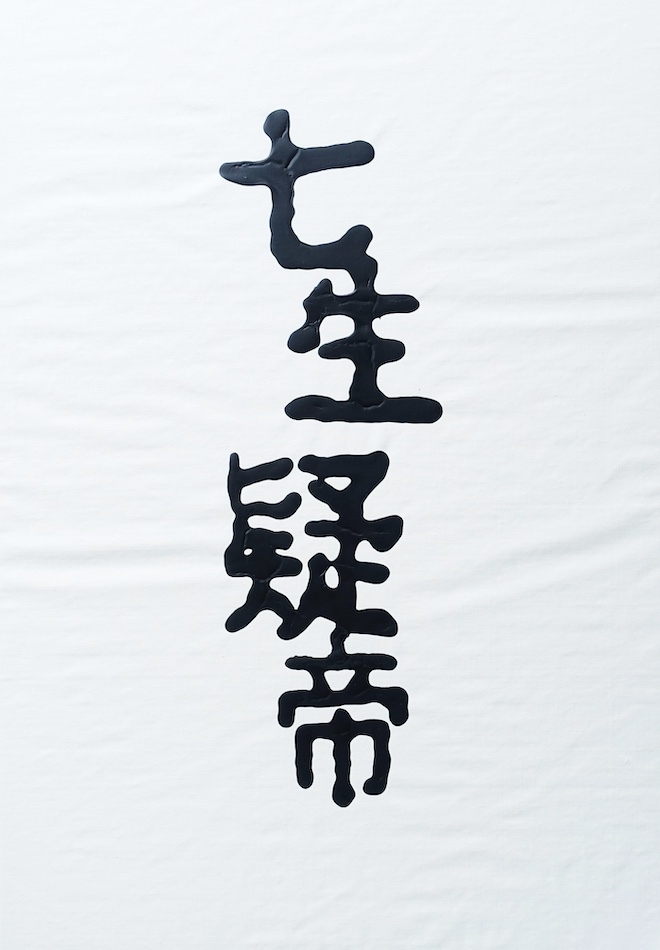

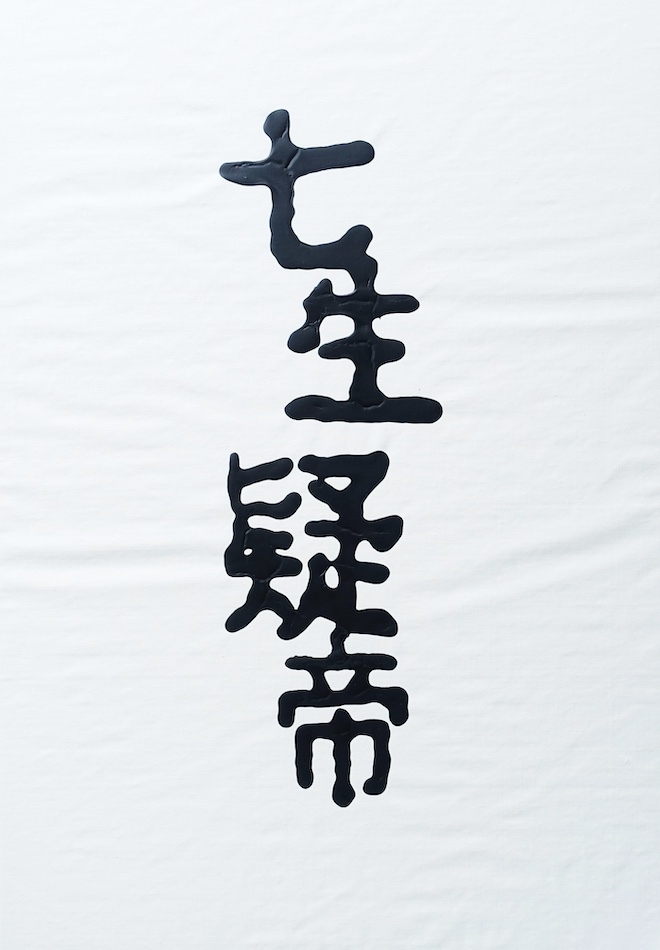

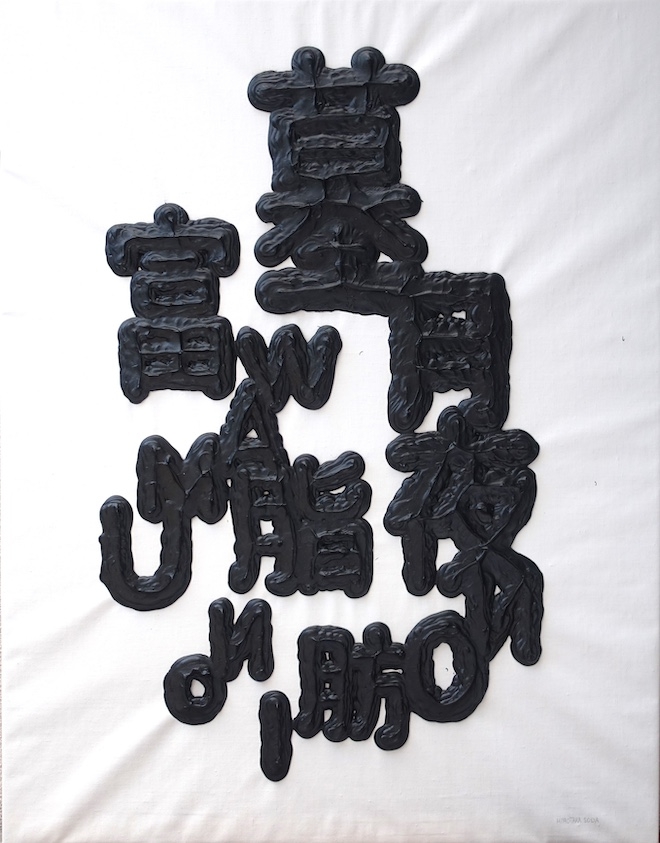

Shichisho gitei, 2024, 162 × 112 cm

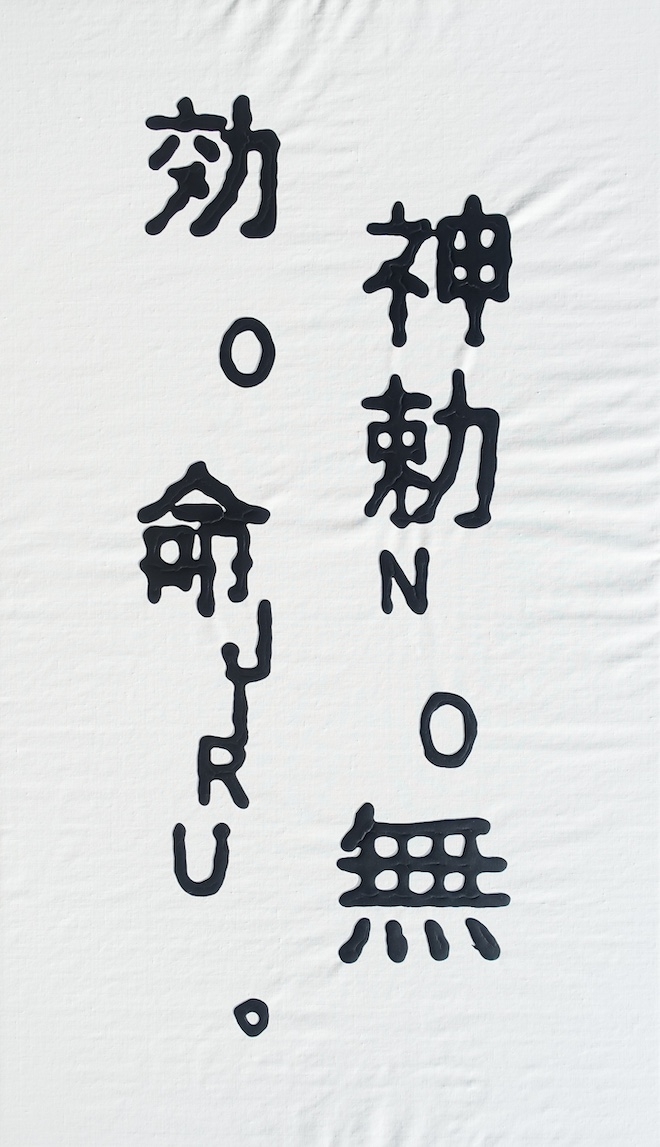

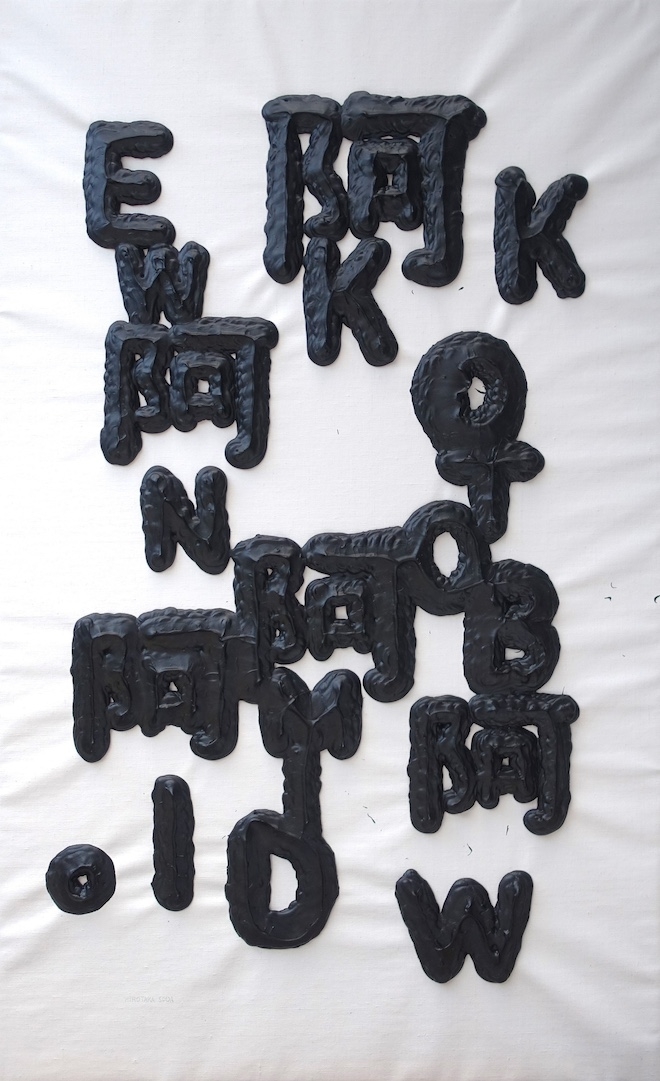

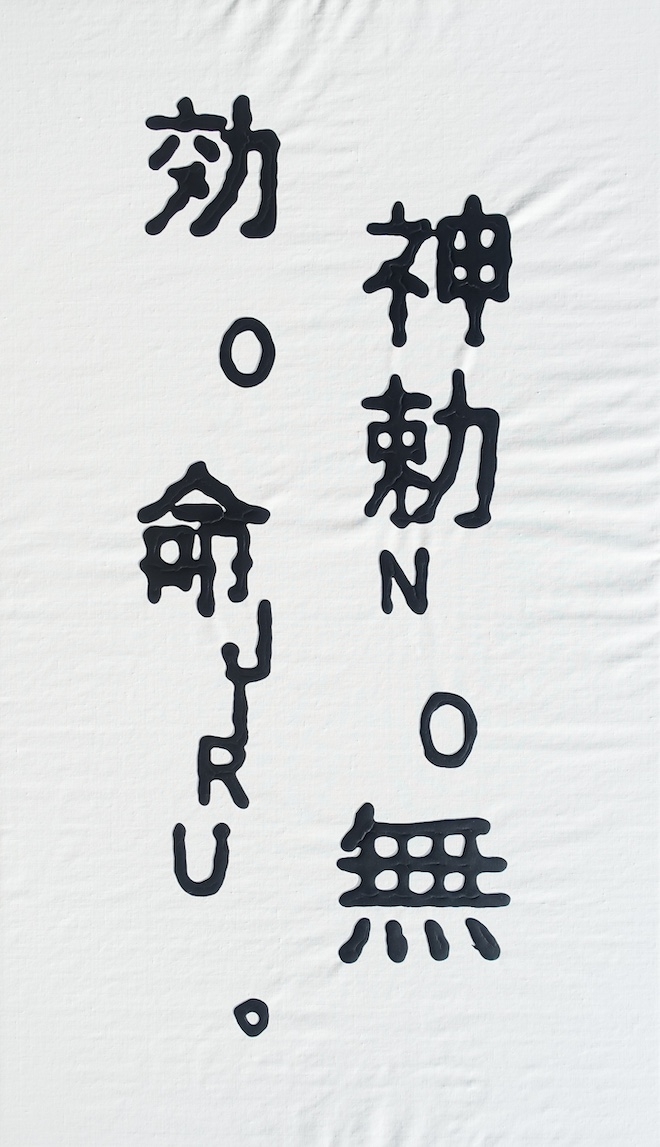

Shinchoku no muko o meijiru., 2024, 184 × 112 cm

*

Taking language as one’s subject matter and expressing language equate to an awareness that words are in every respect ready-mades and that their essence is rooted in the fundamental political nature of human society. Words were not created by anyone in particular, but because they are not generated spontaneously, they are artificial things or “ready-mades” provided to newborn babies as things that are “already made.” Even if they are one’s “native language,” words can by no means be internalized. Moreover, as a system of differentiated sounds, words are continually changing and from the outset there are no clear boundaries between one language and another. In fact, German, Dutch and English represent a gradation extending out spatially and temporally, and it was none other than the politics of “nationalism” that rose in the 18th century that caused them to separate into individual “languages.” As for systems of writing, these were invented by societies as they came to deal with large populations that exceeded the human faculty of memory and the accompanying large volumes of data and are clearly artificial things, which, as they reached the stage where they became linked to print media, changed from written records of individuals into norms in the form of orthographies. “National languages,” “native languages,” “writing” and “orthographies” are all products of politics.

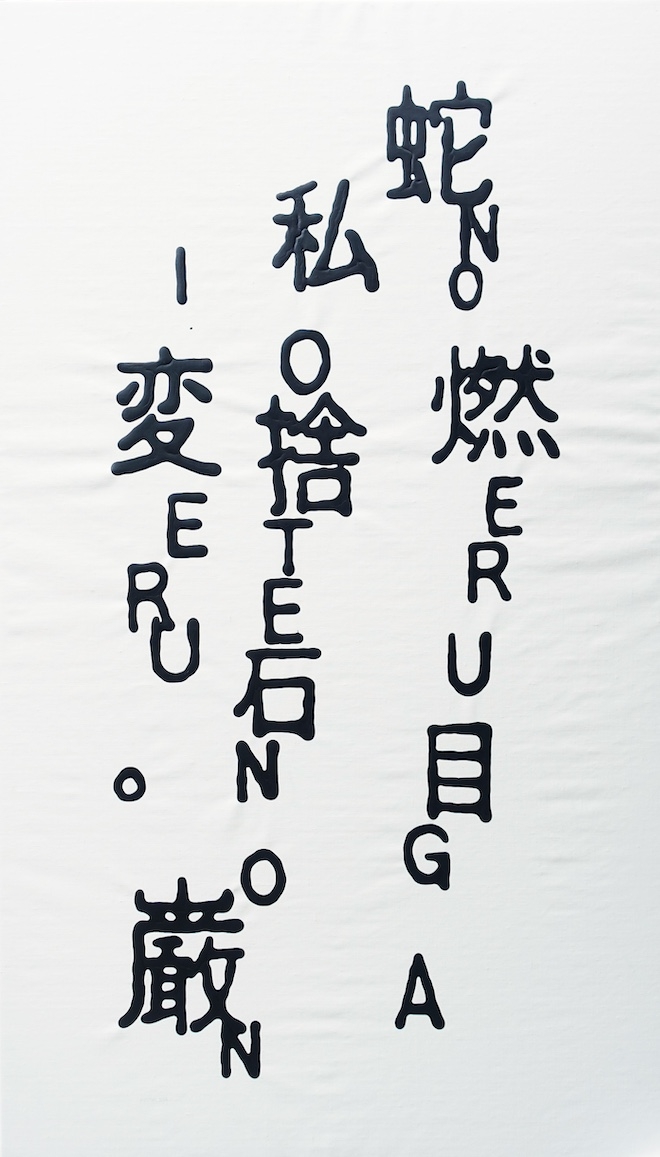

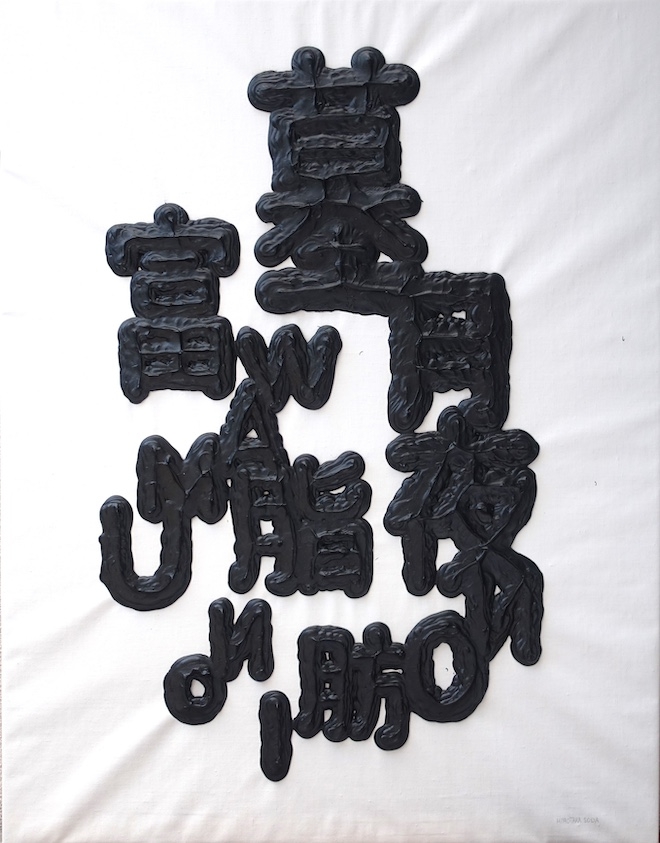

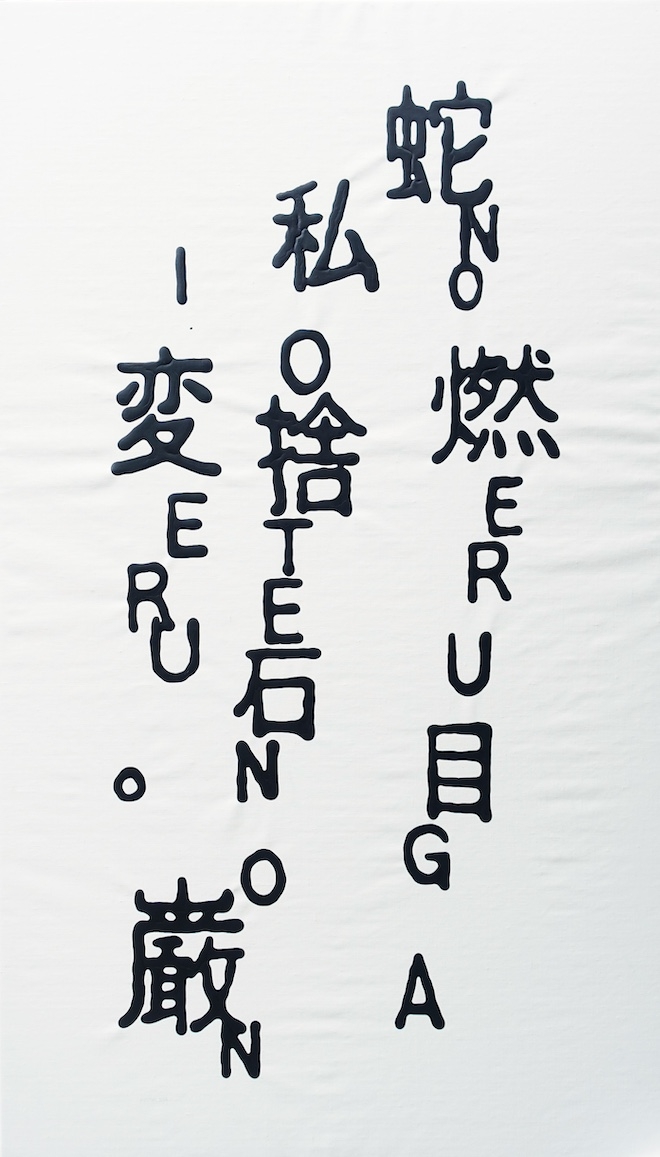

Hebi no moeru mega watashi o suteishi no iwao ni kaeru., 2024, 184 × 112 cm

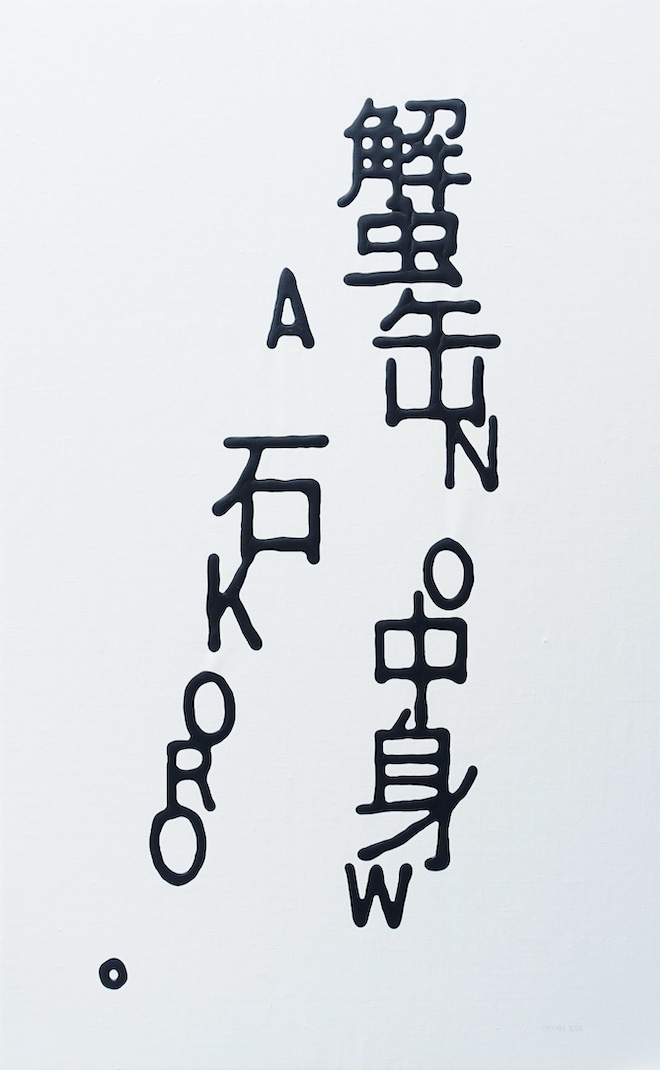

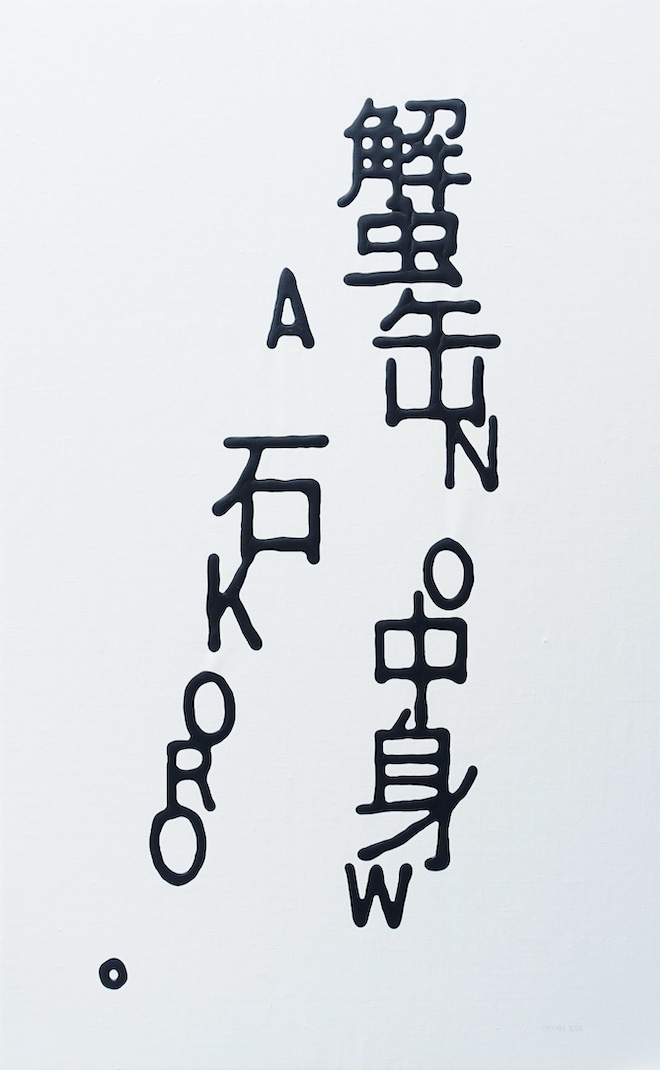

Kanikan no nakami wa ishikoro., 2024, 116.7 × 72.7 cm

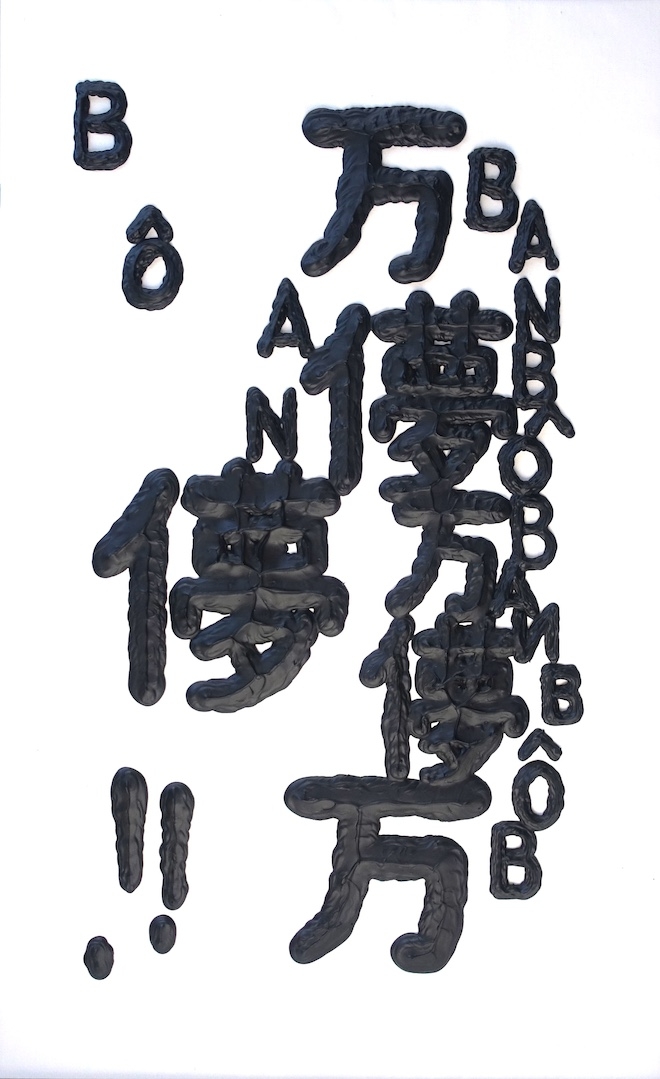

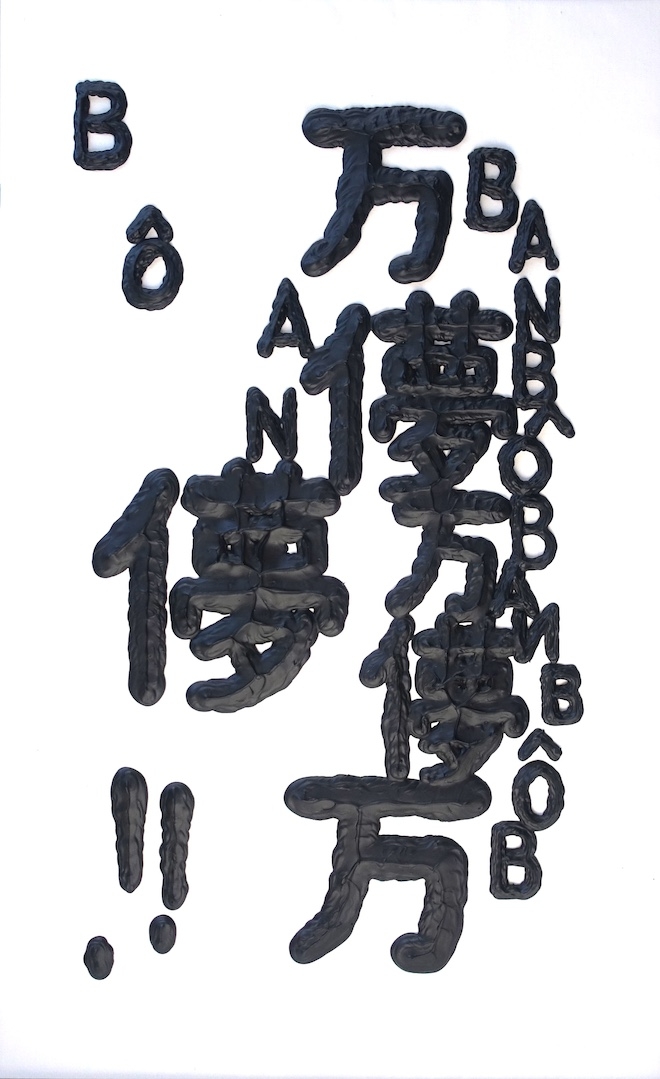

Banbo banbo banbo!!, 2024, 130 × 80 cm

*

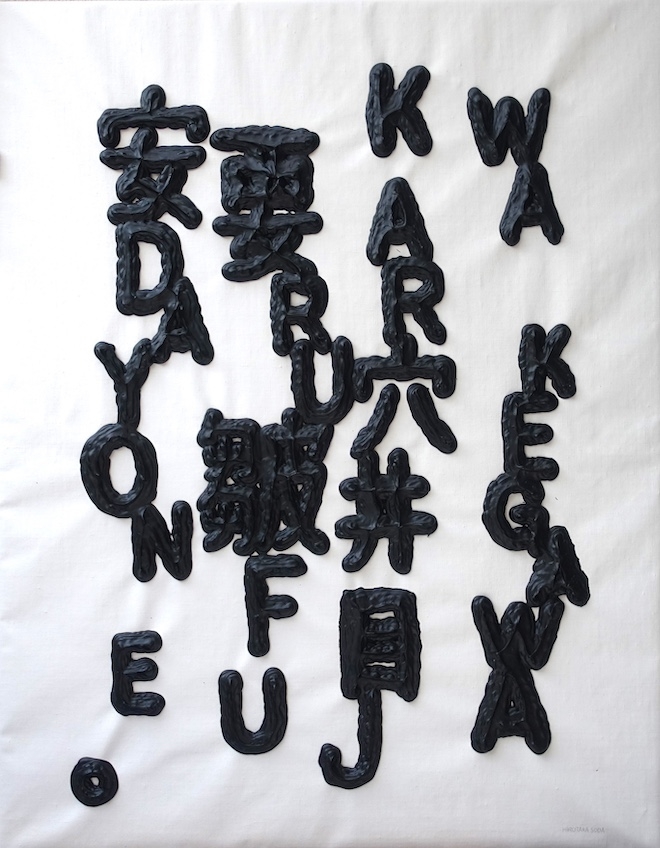

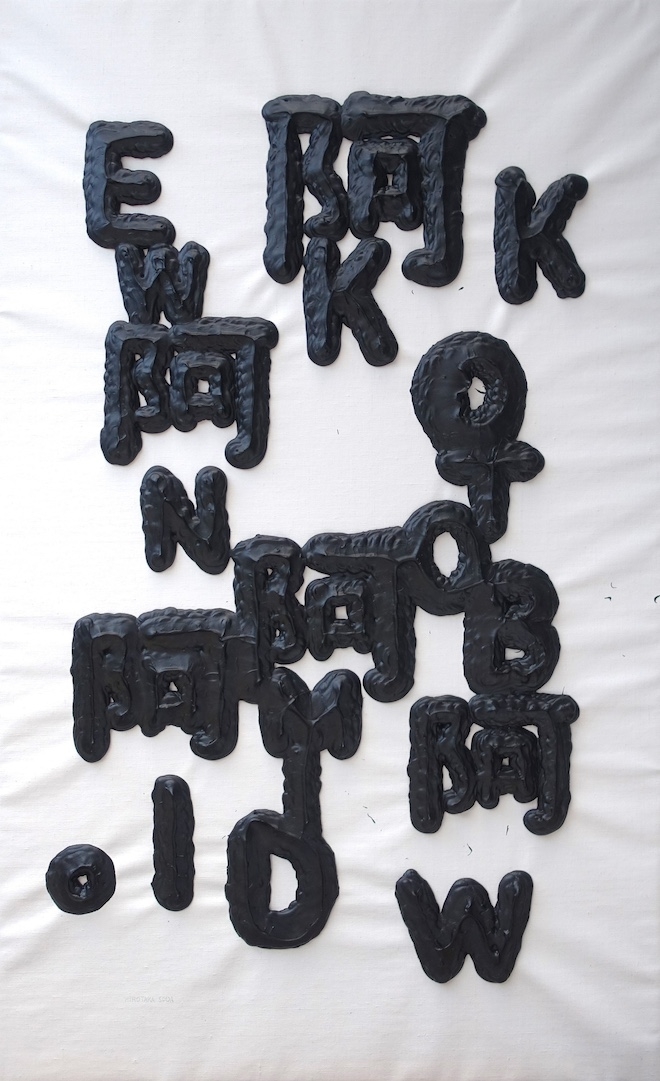

Soda Hirotaka’s calligraphy/language art addresses one-by-one and carefully turns into artworks these and other political aspects concerning the Japanese language. These works have as their basic form “Japanese” words expressed in kanji (up to the prewar era when classical Chinese was worshipped) and Latin script (since the postwar era when the West is worshipped) using asphalt (both a symbol of reconstruction and a symbol of oppression in the sense that it covers the ground) on bare canvas (Japan turned into burnt fields). There is unlimited diversity in the politics of words, and Soda is always preparing a corresponding diversity of expression. The diversity of Soda’s works responds delicately and sensitively to the micro politicalness that words emit in every situation. Soda’s first solo show at the Kita Modern Art Museum will no doubt demonstrate this to the full.

Kotoba wa kami dewa nai., 2024, 130.5 × 80.3 cm

Wake ga wakaranai mejirushi wa fuan dayone. No.2, 2024, 116.7 × 91 cm

Tsukiyo no haka wa shibo ni tomu., 2024, 117 × 91 cm

Soda Hirotaka (b. 1974; from Kyoto)

Graduated in fine arts (oil painting) from Kyoto Seika University. He began participating in Art Shodo in 2019, catching the attention of Shimizu Minoru, and has since participated in ASC exhibitions almost every year. In 2023, he exhibited at Art Shodo’s “Shodo New Age” exhibition, where he won the Shimizu Minoru Award.

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University

“Soda Hirotaka Exhibition: Nihongo no shoji” is being held at the Kita Modern Art Museum through December 1, 2024.