Cultural Currency 31: Tanaka Shingo "Zarathustra" @2kw Gallery

“Now come, fire!” 1

By Shimizu Minoru

2025.01.14

Photo by Satow Takehiro

For the ceramicist Koie Ryōji (1938–2020), the essence of ceramics was baking with fire. When natural clay is baked with fire, it becomes human work, and when human work is destroyed by fire it returns to nature. The “fire” given to humans by Prometheus is the origin of culture, and at the same time “fire” brings about a regression to nature and a resolution of things into their elements (“earth to earth, ashes to ashes”). Ceramics is the art of this cycle of human work and nature, and transcends the conflict between the two. Whereas the “ethics of as-it-is-ness” that runs through modernism is ultimately the dialectics of human work and nature, artificiality and as-it-is-ness, the system and everything outside it, and so on; the act of “firing” connects as is two opposites as interchangeable things, so that nature becomes human work when it is burned, and human work becomes nature when it is burned. This realization on the part of Koie was simple yet profound.

Tanaka Shingo has consistently made the act of burning with fire the core of his expression. “trans,” the signature-like series of works that made him known to the world, involved burning parts of white, geometrical, three-dimensional objects to reveal that they were made from layers of folded paper. In other words, in the process of burning human work and turning it back into nature, layers emerge. For Tanaka, fire was a technique whereby burning human work (the direction being human work→nature) becomes as-it-is expression (the appearance of layered construction).

Tanaka Shingo has consistently made the act of burning with fire the core of his expression. “trans,” the signature-like series of works that made him known to the world, involved burning parts of white, geometrical, three-dimensional objects to reveal that they were made from layers of folded paper. In other words, in the process of burning human work and turning it back into nature, layers emerge. For Tanaka, fire was a technique whereby burning human work (the direction being human work→nature) becomes as-it-is expression (the appearance of layered construction).

Now, the real world can be considered as neither 100 percent “human work” nor 100 percent “nature,” but a zone in between the two. It is a world of human work that has not completely returned to nature (i.e. “waste”) and of nature that has not completely become human work (i.e. “material”). From here, “re:trans” and “transtructure,” the series that continue on from “trans,” express the “collaging” of layers by burning “waste” as “material” for artworks. Both “re:trans” and “transtructure” consist of constructions of sorts made by gathering together waste material, parts of which are burned black. Layers arise from the skillful distribution of the waste, color planes and burning. Here, collage refers to the process of building up layers, and at this stage the key point is that the hierarchical relationship of the overlapping layers cannot be uniquely determined, or in other words that the basal plane of all the layers must not be perceived. At first, the vividness of the waste and burn marks dominated, but gradually the artist’s technique improved, resulting in refined collage work. At the same time, however, the scorch marks turned into mere black bordering, and the meaning of “burning with fire” tended to get lost. With the “transtructure” series, an emphasis was placed on simple structures (frame-like grids), and the aspect of the structure having collapsed due to being burned by fire was restored.

Now, the real world can be considered as neither 100 percent “human work” nor 100 percent “nature,” but a zone in between the two. It is a world of human work that has not completely returned to nature (i.e. “waste”) and of nature that has not completely become human work (i.e. “material”). From here, “re:trans” and “transtructure,” the series that continue on from “trans,” express the “collaging” of layers by burning “waste” as “material” for artworks. Both “re:trans” and “transtructure” consist of constructions of sorts made by gathering together waste material, parts of which are burned black. Layers arise from the skillful distribution of the waste, color planes and burning. Here, collage refers to the process of building up layers, and at this stage the key point is that the hierarchical relationship of the overlapping layers cannot be uniquely determined, or in other words that the basal plane of all the layers must not be perceived. At first, the vividness of the waste and burn marks dominated, but gradually the artist’s technique improved, resulting in refined collage work. At the same time, however, the scorch marks turned into mere black bordering, and the meaning of “burning with fire” tended to get lost. With the “transtructure” series, an emphasis was placed on simple structures (frame-like grids), and the aspect of the structure having collapsed due to being burned by fire was restored.

Not giving up skillful, beautiful layer collaging, yet avoiding materiality that is so strong it evokes the embers of a wooden house (!), while still retaining a connection with the fundamental concept of “fire”—the diverse development of Tanaka’s practice can all be considered as a partial response to these problems.

Not giving up skillful, beautiful layer collaging, yet avoiding materiality that is so strong it evokes the embers of a wooden house (!), while still retaining a connection with the fundamental concept of “fire”—the diverse development of Tanaka’s practice can all be considered as a partial response to these problems.

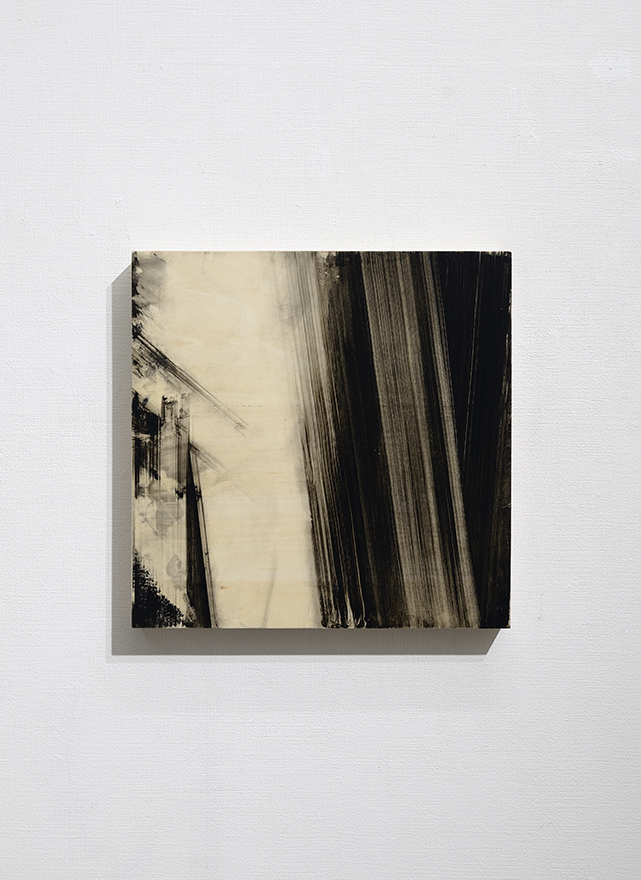

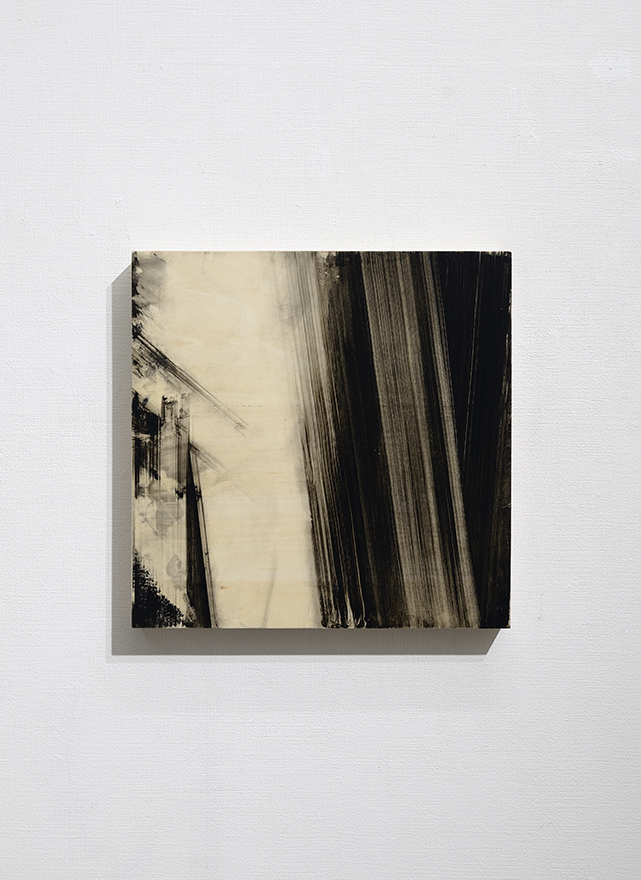

Zarathustra). Out of this process of painting and erasing, erasing and painting, arose picture planes in which complex traces of painting over and wiping off intersect, marking the birth of the “transitional stroke” series featuring band-like planes complexly overlapping each other. This exhibition represents a further development of this with the color palette limited to black and white. Though not true for all the works, this development succeeded beautifully. 2

The problem is that this is not particularly new expression. “The first mark made on a canvas destroys its literal and utter flatness…” (Clement Greenberg). Because with this first application of paint, a layer forms between it and the surface of the support, transforming the physical flatness of the support into a visual flatness in the form of the “picture plane.” When the basal plane underpinning a painting, plane A, has the heterogeneous element B added to it, a layer forms between A and B. Consequently, “it is a strictly pictorial, strictly optical third dimension.” 3 Furthermore, as Jackson Pollock’s “cut-outs” demonstrated, even if the “first mark” is a “first erasure,” a layer still forms.

Using both “painting” and “erasing” for the purposes of layer collaging is in fact an orthodox method. In painting, as long as the blank surface of the support is not left exposed (by completely erasing the paint that has been applied), “painting” and “erasing” form a harmonious whole in the context of the actions of applying a new layer of paint, painting over it in white and wiping it off. In other words, these are completely normal painterly actions. There is no shortage of examples even among work by great masters, including Willem de Kooning’s late abstract paintings among works made using brushes, and Gerhard Richter’s abstract paintings among works made using palette knifes or squeegees.

Of course, because there is no completely new expression in painting, earlier examples by great masters can be considered as historical reference points for Tanaka’s works. One might also add that paintings in which horizontal/vertical bands appear and disappear are perhaps also connected to Hans Richter’s experimental films, including Rhythmus 21 (1921).

A more substantial problem is that as long as the technique used in the “transitional stroke” series—competition between the conflicting elements of “painting” and “erasing”—is in the final analysis nothing more than a replacement for the act of “making paintings,” then it is too simple as a rereading of the concept of “fire.” When technique comes first, art quickly degenerates into refined mannerism. This exhibition was a sincere response by the artist to the above-mentioned problems, and it must be granted that as an exhibition it was a success. However, this success is dangerous. I am not saying it should be burned down (!), but now more than ever Tanaka should perhaps be confronting fire.

The problem is that this is not particularly new expression. “The first mark made on a canvas destroys its literal and utter flatness…” (Clement Greenberg). Because with this first application of paint, a layer forms between it and the surface of the support, transforming the physical flatness of the support into a visual flatness in the form of the “picture plane.” When the basal plane underpinning a painting, plane A, has the heterogeneous element B added to it, a layer forms between A and B. Consequently, “it is a strictly pictorial, strictly optical third dimension.” 3 Furthermore, as Jackson Pollock’s “cut-outs” demonstrated, even if the “first mark” is a “first erasure,” a layer still forms.

Using both “painting” and “erasing” for the purposes of layer collaging is in fact an orthodox method. In painting, as long as the blank surface of the support is not left exposed (by completely erasing the paint that has been applied), “painting” and “erasing” form a harmonious whole in the context of the actions of applying a new layer of paint, painting over it in white and wiping it off. In other words, these are completely normal painterly actions. There is no shortage of examples even among work by great masters, including Willem de Kooning’s late abstract paintings among works made using brushes, and Gerhard Richter’s abstract paintings among works made using palette knifes or squeegees.

Of course, because there is no completely new expression in painting, earlier examples by great masters can be considered as historical reference points for Tanaka’s works. One might also add that paintings in which horizontal/vertical bands appear and disappear are perhaps also connected to Hans Richter’s experimental films, including Rhythmus 21 (1921).

A more substantial problem is that as long as the technique used in the “transitional stroke” series—competition between the conflicting elements of “painting” and “erasing”—is in the final analysis nothing more than a replacement for the act of “making paintings,” then it is too simple as a rereading of the concept of “fire.” When technique comes first, art quickly degenerates into refined mannerism. This exhibition was a sincere response by the artist to the above-mentioned problems, and it must be granted that as an exhibition it was a success. However, this success is dangerous. I am not saying it should be burned down (!), but now more than ever Tanaka should perhaps be confronting fire.

——————————–

——————————–

1. The first line of Friedrich Hölderlin’s poem Der Ister / The Ister, “Jetzt komme, Feuer! / Now come, fire!” 2. The works in which ribbon-like planes alone filled the picture plane succeeded, but when arrangements other than this (columnar lines, blurred images) appeared, the resultant compositions hindered the airy layer collaging. 3. Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” in The Collected Essays and Criticism Vol. 4 (University of Chicago Press, 1995), 90. ——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University

——————————–

Tanaka Shingo “Zarathustra” was held at 2kw Gallery from November 30 through December 22, 2024.

trans (cube#03), 2009

re:trans #061, 2018

transtructure #05, 2020

Photo by Mugyuda Hyogo

transitional stroke #19, 2023

Photo by Tomas Svab

*

Tanaka began by rereading the concept of “fire” as “a technique for connecting as is and interchangeably two opposing items” and established the two items as “painting” and “erasing.” He considered the founder of Zoroastrianism, Zarathustra (Zoroaster), as the originator of the oldest dualism in the world (good and evil) and represented the conquest of dualism, or in other words the coexistence of “painting” and “erasing,” as a strikethrough (

transitional stroke #26, 2024

Photo by Satow Takehiro

transitional stroke #30, 2024

Photo by Satow Takehiro

Installation view

Photo by Satow Takehiro

1. The first line of Friedrich Hölderlin’s poem Der Ister / The Ister, “Jetzt komme, Feuer! / Now come, fire!” 2. The works in which ribbon-like planes alone filled the picture plane succeeded, but when arrangements other than this (columnar lines, blurred images) appeared, the resultant compositions hindered the airy layer collaging. 3. Clement Greenberg, “Modernist Painting,” in The Collected Essays and Criticism Vol. 4 (University of Chicago Press, 1995), 90. ——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University

——————————–

Tanaka Shingo “