Artist-in-Residence (4):

The eyes of a pilot drifting through the world

By Hinuma Teiko

◉ The opening of the Aomori Contemporary Art Centre

After working as an assistant at a water-based woodblock print AIR program, for 12 years following the establishment of the Aomori Contemporary Art Centre (ACAC) preparatory office in 1999 I had the opportunity to participate in administration. This was my first full-scale involvement in an AIR site. It was also a major turning point in my life in that I met the artist, performer and inaugural director of the ACAC, the late Hamada Goji [*1], who became my third mentor following on from Tsuchiya Kimio and Kadota Keiko.

The ACAC opened in December 2001 as a project commemorating the centennial of Aomori becoming a city. Making the most of the area’s rich natural environment, it was established as a new creative space where artists and local residents could meet, a new cultural facility centered not on a building (box) and works of art (things), but on people. At the foot of Mount Hakkoda and close to the Moya ski resort, it supports and promotes expression by artists mainly in the field of contemporary art and runs a variety of art education and other community-oriented programs while making the most of the unique atmosphere created by the natural setting and the architecture designed by Ando Tadao. Through the AIR programs in particular, the facility has greatly stimulated artists who concern themselves not only with the natural environment but also with the cultural background rooted in Aomori’s climate, giving rise to many challenging, experimental artworks. I am delighted that the ACAC marked its 20th anniversary in 2021 having overcome numerous difficulties and problems, from a change in management structure to the coronavirus pandemic. I would like to pay tribute to the efforts of the many people who have supported it and stress how proud I am to have been involved.

At this point I would like to relate an episode that led to the establishment of the ACAC. When it was first being considered, what local residents wanted as a project to commemorate Aomori’s centennial was “to have their own art museum like other cities.” But because preparations for the establishment of the prefectural Aomori Museum of Art were also underway at the time, the administration led by the then mayor, Sasaki Seizo, was exploring options for cultural projects unique to Aomori city. It was around this same time that Hamada Goji donated to the city posthumous works by his father, Hamada Eiichi, [*2] an artist who was admired locally, and so as part of the discussions the subject of AIR arose. It was largely as a result of this chance encounter that preparations for the establishment of the ACAC began. People in the art world at the time were no doubt more than a little surprised when Hamada Goji, who had a wealth of overseas experience with AIR as an artist, was installed as director of a government-administered cultural facility, a major event that also focused public attention on AIR programs, which until then were mostly alternative, artist-run initiatives.

[*1] Born 1944 in Aomori; graduated from Tokyo University of the Arts in 1968 with a degree in sculpture. A pioneer of performance art in Japan, he was active worldwide, participating in AIRs in Australia, Canada, Germany, among other countries. He also worked as a producer for various art programs and international exhibitions, and conducted research on the art of the Uilta people, a northern minority, and indigenous peoples in Canada and Australia. Died in 2016.[*2] Born 1911 in Aomori. Studied under the printmaker Kon Junzo. Selected for the Nika Art Exhibition in 1962. Received the Aomori Prefecture Medal of Honor in 1993. Died in 1997.

◉ The importance of artist initiatives

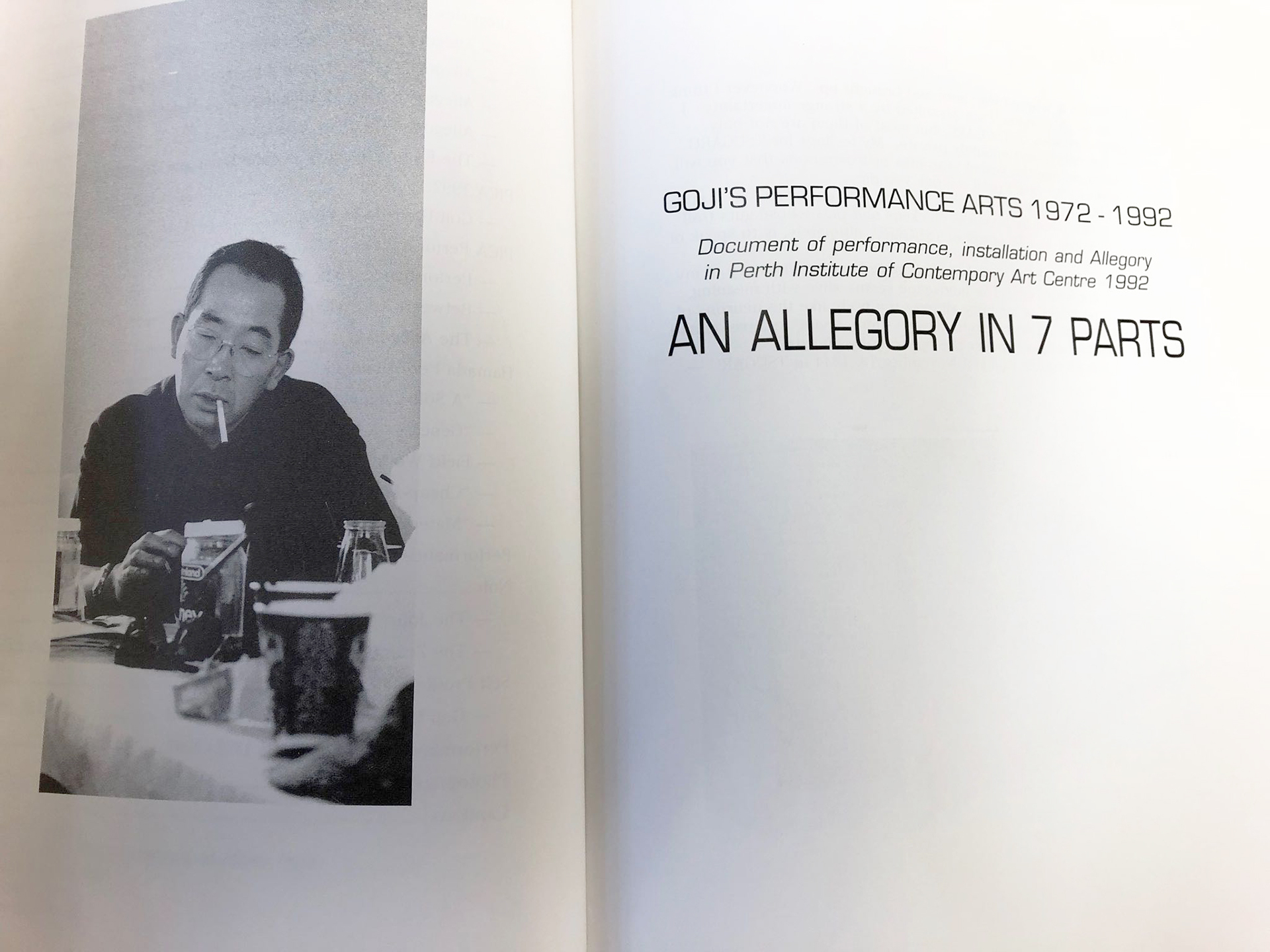

Hamada Goji was a pioneer of performance art in Japan. After studying sculpture at Tokyo University of the Arts, he staged his first performance, Beautiful Losers, by the Berlin Wall in 1972, following which he presented installations and other works and held performances all over the world, including in South Korea, Australia, Germany, Canada and Poland. In particular, Gui no Kodogaku (The behavioral science of allegory), [*3] a performance symposium held over seven days at the Seibu-Kodo Hall at Kyoto University involving numerous participants from a range of genres, is something of a hidden legend still talked about today.

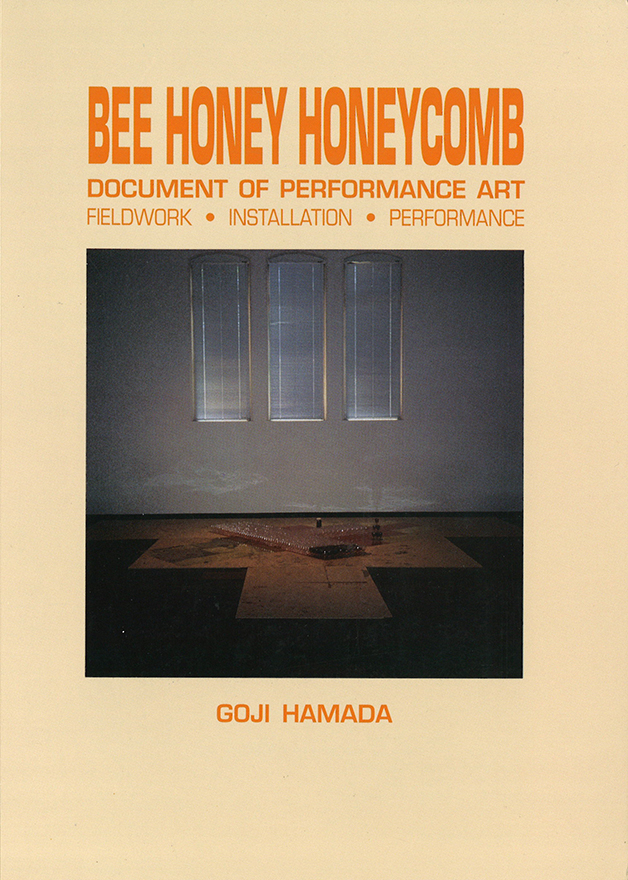

《BEE HONEY HONEYCOME – DOCUMENT OF PERFORMANCE ART》Goji Hamada (Published by PICA Press 1994)

The period from the late 1970s to the 1990s when Hamada was most active was a period of bewildering social change centered on the global economy, amid which artists sought new, so-called “alternative” expression and places to show their work outside of art museums and galleries. For these artists, AIR programs that enabled them to engage in art practices while moving freely around the world were the stuff of great hopes and dreams. Hamada made full use of AIR programs in various countries, regularly producing and performing in as many as 50 events a year, often in vacant buildings and closed schools he found himself. According to the artist, these were opportunities to explore the strengths of his own expression through repeated destruction and regeneration. For Hamada, then, his involvement in the ACAC was a chance to give back to the AIR programs and artists that had welcomed him. He often spoke of wanting artists to feel welcome to visit him any time with a warm “Hello!” Many artists from Japan and overseas who had trust in Hamada were drawn to the ACAC where they conversed with each other, made art and built strong networks. With Hamada’s presence as its cornerstone, the uniqueness of the ACAC has been preserved down through the years.

[*3] Performances, installations, fieldwork, workshops, and symposiums held over seven days. Participants included critics and artists Hasegawa Roku, Kogawa Tesuo, Hattori Tatsuro, Shii Kei, Miura Masashi, Tanikawa Koichi, and Kobayashi Susumu, and butoh dancer Katsura Kan. (October 8–14, 1993, Seibu-Kodo Hall, Kyoto University).◉ Beyond destruction and regeneration

My final task at the ACAC was to conduct an interview with Hamada that was scheduled to appear in the ACAC’s annual report, AC2 No. 12 (Aomori Contemporary Art Centre, Aomori Public University, 2011). I wanted to look back over the period and events since the ACAC’s establishment as it approached its 10th anniversary and pass on to the next generation Hamada’s thoughts on the nature of AIR programs, as well as thanking him for the many experiences he had given us all. I would like to quote two memorable passages from the final article.

“It is a fact that society is not in a happy state, and I think perhaps we need to remake the skin that is on the verge of going bad. There will be many sacrifices, but I think AIR still has the right to say this, and we still need to try out various methodologies. If we can re-present to society whether the ACAC’s AIR program is truly capable of playing this role, we should do so as soon as possible. Just as it is only by repeating destruction and regeneration that we accumulate wisdom for living.”

“The world is constantly on the move 24 hours a day and there are wars and various things going on. Amid the movement of artists and interactions among people, new maps come into existence. And we become the eyes of a pilot gazing down at the world. I would like to see AIR programs becoming such places and playing such roles.”

If he were alive, I wonder what Hamada Goji, the artist, would re-present here and now. Joseph Beuys, an artist Hamada held in high esteem, flew in bombers as a member of the Luftwaffe during World War Two. He drew on his experience of being rescued by nomadic Tatar tribesmen after his plane crashed on the Crimean Front in developing his unique art practice, giving rise to the concept of “social sculpture.” Despite the political and physical divisions imposed on us by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and other events from 2020 to the present, artists have continued to engage in various activities and to create art. And AIR programs have continued to provide places that accept these artists. Among the countless statements Hamada left behind, there are many that seem to predict the current situation. His absence is a sad reality, but I am continually rereading the statements he left behind and thinking about what AIR programs can do.(To be continued)

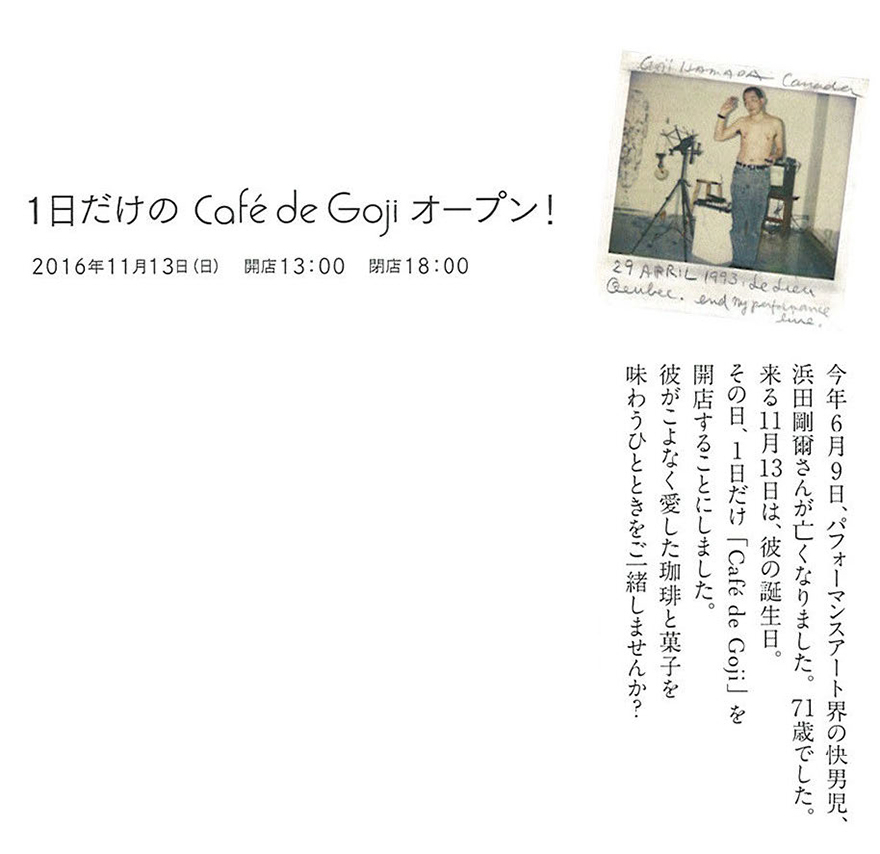

The invitation to Hamada Goji farewell “Cafe de Goji”. In memory of Hamada, who loved having tea.

The event was organized by Ken Awazu, the eldest son of Kiyoshi Awazu, a designer who was a close friend of Hamada.

AIR (2): AIR —Encounters with place, unique dialog-driven expression, cross-cultural respect and understanding

AIR (3): Perspectives on the transmission of culture, AIR, and sustainability

AIR (5): Natural disaster and AIR—Rikuzentakata (1)

AIR (6): Natural disaster and AIR—Rikuzentakata (2)

AIR (7): Networks that connect with the world, AIRs that connect to the future

Hinuma Teiko

Professor at Joshibi University of Art and Design, head of the AIR Network Japan Preparatory Committee, Art Director at Tokiwa Museum. Hinuma worked at the preparatory office to establish the Aomori Contemporary Art Centre from 1999 and served as a curator there until 2011, providing support for artists, primarily through residencies for artists, and planning and running various projects and exhibitions. She has filled various other positions including Project Director of the Saitama Triennale 2016 and Program Director of the Rikuzentakata AiR Program.